2023 ANNUAL REPORT OF

THE BOARDS OF TRUSTEES OF THE

FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND

FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE

TRUST FUNDS

COMMUNICATION

From

THE BOARDS OF TRUSTEES,

FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND

FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE

TRUST FUNDS

Transmitting

THE 2023 ANNUAL REPORT OF

THE BOARDS OF TRUSTEES OF THE

FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND

FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE

TRUST FUNDS

(III)

LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL

____________________

BOARDS OF TRUSTEES OF THE

FEDERAL HOSPITAL INSURANCE AND

FEDERAL SUPPLEMENTARY MEDICAL INSURANCE TRUST FUNDS,

Washington, D.C., March 31, 2023

HONORABLE KEVIN MCCARTHY,

Speaker of the House of Representatives

HONORABLE KAMALA D. HARRIS,

President of the Senate

DEAR MR. SPEAKER AND MADAM PRESIDENT:

We have the honor of transmitting to you the 2023 Annual Report of the Boards of Trustees of the

Federal Hospital Insurance Trust Fund and the Federal Supplementary Medical Insurance Trust

Fund, the 58th such report.

Respectfully,

JANET YELLEN,

Secretary of the Treasury,

and Managing Trustee of the Trust Funds.

JULIE A. SU,

Acting Secretary of Labor,

and Trustee.

XAVIER BECERRA,

Secretary of Health and Human Services,

and Trustee.

KILOLO KIJAKAZI,

Acting Commissioner of Social Security,

and Trustee.

VACANT,

Public Trustee.

VACANT,

Public Trustee.

CHIQUITA BROOKS-LASURE,

Administrator,

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services,

and Secretary, Boards of Trustees.

(V)

CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 1

II. OVERVIEW ..................................................................................... 9

A. Highlights .................................................................................... 9

B. Medicare Data for Calendar Year 2022 ..................................... 13

C. Medicare Assumptions .............................................................. 15

D. Financial Outlook for the Medicare Program............................ 22

E. Financial Status of the HI Trust Fund ...................................... 28

F. Financial Status of the SMI Trust Fund ................................... 35

G. Conclusion ................................................................................. 44

III. ACTUARIAL ANALYSIS ............................................................. 47

A. Introduction ............................................................................... 47

B. HI Financial Status ................................................................... 48

1. Financial Operations in Calendar Year 2022 ........................ 48

2. 10-Year Actuarial Estimates (2023–2032) ............................. 55

3. Long-Range Estimates ........................................................... 64

4. Long-Range Sensitivity Analysis ........................................... 76

C. Part B Financial Status ............................................................. 81

1. Financial Operations in Calendar Year 2022 ........................ 81

2. 10-Year Actuarial Estimates (2023–2032) ............................. 88

3. Long-Range Estimates ......................................................... 101

D. Part D Financial Status .......................................................... 103

1. Financial Operations in Calendar Year 2022 ...................... 103

2. 10-Year Actuarial Estimates (2023–2032) ........................... 107

3. Long-Range Estimates ......................................................... 116

IV. ACTUARIAL METHODOLOGY AND PRINCIPAL ASSUMPTIONS 119

A. Hospital Insurance .................................................................. 119

B. Supplementary Medical Insurance .......................................... 131

1. Part B ................................................................................... 131

2. Part D ................................................................................... 144

C. Private Health Plans ............................................................... 155

D. Long-Range Medicare Cost Growth Assumptions ................... 165

V. APPENDICES ............................................................................. 174

A. Medicare Amendments since the 2022 Report ........................ 174

B. Total Medicare Financial Projections ...................................... 188

C. Illustrative Alternative Projections ......................................... 200

D. Average Medicare Expenditures per Beneficiary .................... 205

E. Medicare Cost-Sharing and Premium Amounts ...................... 208

F. Medicare and Social Security Trust Funds and the Federal

Budget ...................................................................................... 216

G. Infinite Horizon Projections .................................................... 223

H. Fiscal Year Historical Data and Projections through 2032..... 230

I. Glossary .................................................................................... 241

J. List of Tables ............................................................................ 262

J. List of Figures .......................................................................... 266

J. Statement of Actuarial Opinion ............................................... 267

1

I. INTRODUCTION

The Medicare program helps pay for health care services for the aged,

disabled, and individuals with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). It has

two separate trust funds, the Hospital Insurance trust fund (HI) and

the Supplementary Medical Insurance trust fund (SMI). HI, otherwise

known as Medicare Part A, helps pay for inpatient hospital services,

hospice care, and skilled nursing facility (SNF) and home health

services following hospital stays. SMI consists of Medicare Part B and

Part D. Part B helps pay for physician, outpatient hospital, home

health, and other services for individuals who have voluntarily

enrolled. Part D provides subsidized access to drug insurance coverage

on a voluntary basis for all beneficiaries and premium and cost-sharing

subsidies for low-income enrollees. Medicare also has a Part C, which

serves as an alternative to traditional Part A and Part B coverage.

Under this option, beneficiaries can choose to enroll in and receive care

from private Medicare Advantage and certain other health insurance

plans. Medicare Advantage and Program of All-Inclusive Care for the

Elderly (PACE) plans receive prospective, capitated payments for such

beneficiaries from the HI and SMI Part B trust fund accounts; the

other plans are paid from the accounts on the basis of their costs.

The Social Security Act established the Medicare Board of Trustees to

oversee the financial operations of the HI and SMI trust funds.

1

The

Board has six members. Four members serve by virtue of their

positions in the Federal Government: the Secretary of the Treasury,

who is the Managing Trustee; the Secretary of Labor; the Secretary of

Health and Human Services; and the Commissioner of Social Security.

Two other members are public representatives whom the President

appoints and the Senate confirms. These positions have been vacant

since 2015. The Administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid

Services (CMS) serves as Secretary of the Board.

The Social Security Act requires that the Board, among other duties,

report annually to the Congress on the financial and actuarial status

of the HI and SMI trust funds. The 2023 report is the 58th that the

Board has submitted.

With two exceptions, the projections are based on the current-law

provisions of the Social Security Act. The first exception is that the

Part A projections disregard payment reductions that would result

from the projected depletion of the Medicare HI trust fund. Under

1

The Social Security Act established separate boards for HI and SMI. Both boards have

the same membership, so for convenience they are collectively referred to as the

Medicare Board of Trustees in this report.

Introduction

2

current law, payments would be reduced to levels that could be covered

by incoming tax and premium revenues when the HI trust fund was

depleted. If the projections reflected such payment reductions, then

any imbalances between payments and revenues would be

automatically eliminated, and the report would not fulfill one of its

critical functions, which is to inform policymakers and the public about

the size of any trust fund deficits that would need to be resolved to

avert program insolvency. To date, lawmakers have never allowed the

assets of the Medicare HI trust fund to become depleted.

The second exception is that the elimination of the safe harbor

protection for manufacturer rebates, which was finalized in a rule

released in November of 2020, is not reflected in the Part D projections.

This final rule imposed a January 1, 2022 effective date; however,

implementation was initially delayed until January 1, 2023. Since

then, enacted legislation has three times imposed a moratorium on

implementation, and it is currently delayed until January 1, 2032.

Therefore, the likelihood of this rule taking effect is highly uncertain.

The Medicare projections have been significantly affected by the

enactment of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA). This legislation

has wide-ranging provisions, including those that restrain price

growth and negotiate drug prices for certain Part B and Part D drugs

and that redesign the Part D benefit structure to decrease beneficiary

out-of-pocket costs. The law takes several years to implement,

resulting in very different effects by year. The Part D benefit

enhancements are implemented by 2025, for example, before the

negotiation provisions that are effective in 2026 can have any spending

reduction impact. The total effect of the IRA is to reduce government

expenditures for Part B, to increase expenditures for Part D through

2030, and to decrease Part D expenditures beginning in 2031. Part B

savings are due to the substantial lowering of payments, relative to

current reimbursement, as a result of negotiated prices. Part D

ultimately generates cost savings at the end of the 10-year period, but

many of the gains from negotiated prices and lower trends are initially

more than offset by increased benefits and decreased manufacturer

rebates.

The Board of Trustees assumes that the IRA will affect the ultimate

long-range growth rates for Part B and Part D drug spending

differently. For Part B drugs, since the Trustees do not anticipate that

the market pricing dynamics will be much different from those prior to

the implementation of the IRA, they continue to assume that per capita

spending growth rates will be similar to those for overall per capita

national health expenditures. On the other hand, for Part D drugs, the

Introduction

3

Trustees assume that per capita spending will grow 0.2 percentage

point more slowly than per capita national health expenditures, since

the inflation provisions of the IRA are likely to result in a trend rate

that is lower than, and price growth that is closer to, the Consumer

Price Index (CPI).

Beginning in 2020, the Medicare program was dramatically affected by

the COVID-19 pandemic. Spending was directly affected by the

coverage of testing and treatment of the disease. In addition, several

regulatory policies and legislative provisions were enacted during the

public health emergency that increased spending, and the use of

telehealth was greatly expanded. More than offsetting these additional

costs in 2020, spending for non-COVID care declined significantly.

Actual fee-for-service per capita spending has been consistently below

the pre-pandemic projections throughout the public health emergency,

even into 2022 as the pandemic had diminishing effects on much of the

economy and the health care delivery system. A number of factors have

contributed to this lower spending, including the net effects of (i) lower

average morbidity among the surviving population from COVID-

related deaths; (ii) a greater share of dual-eligible beneficiaries

enrolling in the Medicare Advantage program; and (iii) the shift of joint

replacement procedures from an inpatient to an outpatient setting.

These reductions are partially offset by certain public health

emergency policies. All of these factors are discussed in more detail

below.

• To estimate the morbidity effect, COVID-related decedents were

matched to 2015 patients and were followed for 48 months. The

patients were matched

2

based on demographic, health status, and

acute/post-acute care patterns in the period prior to their

contracting COVID and were determined to have spending that

was much higher than average. This approach was replicated for

each year’s COVID decedents. As a result, the surviving population

had spending that was lower than average. This impact decreases

over time until there is no effect on the projections after 2029.

• The share of Medicare beneficiaries enrolled in the Medicare

Advantage program has increased considerably over the last two

2

The approach used a two-stage nearest-neighbor-match methodology. The first step

forced an exact match on gender, disability status, ESRD status, institutional status,

dual eligibility, 5-year age group, chronic condition count, inpatient payment grouping,

SNF payment grouping, and chronic kidney disease. The second step then chose a

comparison patient within cohort by minimizing a Euclidian distance metric on

quarterly fee-for-service Part A and Part B spending patterns.

Introduction

4

decades. This change would not have an impact on the average fee-

for-service cost if those enrolling in the program had average fee-

for-service spending. Over the last several years, however, a

greater proportion of those dually eligible for Medicaid and

Medicare have been enrolling, and dual-eligible beneficiaries have

a significantly higher average level of spending than non-dual

beneficiaries. As a result, the additional dual-eligible enrollments

have decreased the average fee-for-service per capita cost—

affecting, in turn, the trends for inpatient hospital, SNF, and home

health spending.

•

Over time, procedures that had previously been provided in the

more expensive inpatient setting have been shifting to the lower-

cost outpatient setting. These effects are reflected in the Medicare

service-level history and are similarly incorporated into the

expected trends for future years.

Prior to 2018, hip and knee replacement surgeries were performed

exclusively in the inpatient setting. Then a shift occurred on

January 1, 2018, when knee replacements were removed from the

inpatient-only list; similarly, on January 1, 2020, hip replacements

were removed from the inpatient-only list, and knee replacements

were allowed to be performed in ambulatory surgical centers. As a

result, the proportion of hip and knee replacement surgeries

performed in the inpatient setting reduced dramatically, causing a

greater shift in spending from the inpatient to outpatient setting

than implicitly assumed.

• A number of policies that are in effect during the public health

emergency affect Medicare spending. One such policy is that, for

inpatient stays for individuals with a COVID diagnosis, payments

to hospitals are increased by 20 percent. Another is that the 3-day

inpatient stay requirement for SNF services has been waived; this

policy has increased SNF spending and decreased spending for

home health services. These effects are assumed to be eliminated

at the end of the public health emergency.

While these factors account for a significant amount of the difference

between actual and expected experience for many of the categories,

others are still largely unexplained. For inpatient hospital, outpatient

hospital, and SNF spending, these unexplained differences are

expected to be eliminated by 2024; for home health services, they are

expected to be gradually eliminated by 2026.

Introduction

5

It should be noted that there is an unusually large degree of

uncertainty with the COVID-related impacts and that future

projections could change significantly as more information becomes

available. The Trustees will continue to monitor developments and

modify the projections in later reports as appropriate.

The Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payments (AAP) Program was

significantly expanded during the COVID-19 public health emergency

period, by both legislative provisions and administrative actions taken

by CMS early on during the emergency. Total payments of

approximately $107.2 billion were made from March 2020 through

June 2021: roughly $67.2 billion from the HI trust fund and

$40.1 billion from the SMI Part B trust fund account. As of January 1,

2023, roughly 99 percent of these amounts have been repaid. The

Trustees assume that the remaining balance will be fully repaid or

converted to an extended repayment schedule by March of 2023.

Although these payments and repayments significantly affected the

timing of expenditures from 2020 through 2022, they have no

cumulative net effect.

A more typical reason for uncertainty in projecting Medicare costs,

especially when looking out more than several decades, is that

scientific advances will make possible new interventions, procedures,

and therapies. Some conditions that are untreatable today may be

handled routinely in the future. Spurred by economic incentives, the

institutions through which care is delivered will evolve, possibly

becoming more efficient. While most health care technological

advances to date have tended to increase expenditures, the health care

landscape is shifting. No one knows whether future developments will,

on balance, increase or decrease costs.

Certain features of current law may result in some challenges for the

Medicare program. Physician payment update amounts are specified

for all years in the future, and these amounts do not vary based on

underlying economic conditions, nor are they expected to keep pace

with the average rate of physician cost increases. These rate updates

could be an issue in years when levels of inflation are high and would

be problematic when the cumulative gap between the price updates

and physician costs becomes large. Payment rate updates for most non-

physician categories of Medicare providers are reduced by the growth

Introduction

6

in economy-wide private nonfarm business total factor productivity

3

although these health providers have historically achieved lower levels

of productivity growth. If the health sector cannot transition to more

efficient models of care delivery and if the provider reimbursement

rates paid by commercial insurers continue to be based on the same

negotiated process used to date, then the availability, particularly with

respect to physician services, and quality of health care received by

Medicare beneficiaries would, under current law, fall over time

compared to that received by those with private health insurance.

Since 1960, U.S. national health expenditure (NHE) growth rates

typically outpaced economic growth rates, though the magnitude of the

differences has been declining. The Trustees have long assumed that

this differential would continue to narrow over the long-term projection

period and that cost-reduction provisions required under current law

would further decrease this gap. Since 2008, average annual NHE

growth has been below historical averages, though it has generally

continued to outpace average annual growth of the economy. There is

some debate regarding whether this recent slower growth in national

health expenditures reflects the impact of economic factors that are

mostly cyclical in nature, such as modest income growth over the last

decade, or factors that would lead to a permanently slower growth

environment, such as structural changes to the health sector that could

result in lower health care cost growth. The Trustees’ outlook for long-

range NHE growth is consistent with the trajectory observed over the

past half century and has not been materially affected by this recent

experience.

Current-law projections indicate that Medicare still faces a substantial

financial shortfall that will need to be addressed with further

legislation. Such legislation should be enacted sooner rather than later

to minimize the impact on beneficiaries, providers, and taxpayers.

3

For convenience the term economy-wide private nonfarm business total factor

productivity will henceforth be referred to as economy-wide productivity. Beginning with

the November 18, 2021 release of the productivity data, the Bureau of Labor Statistics

(BLS) replaced the term multifactor productivity with the term total factor productivity,

a change in name only as the underlying methods and data were unchanged.

Introduction

7

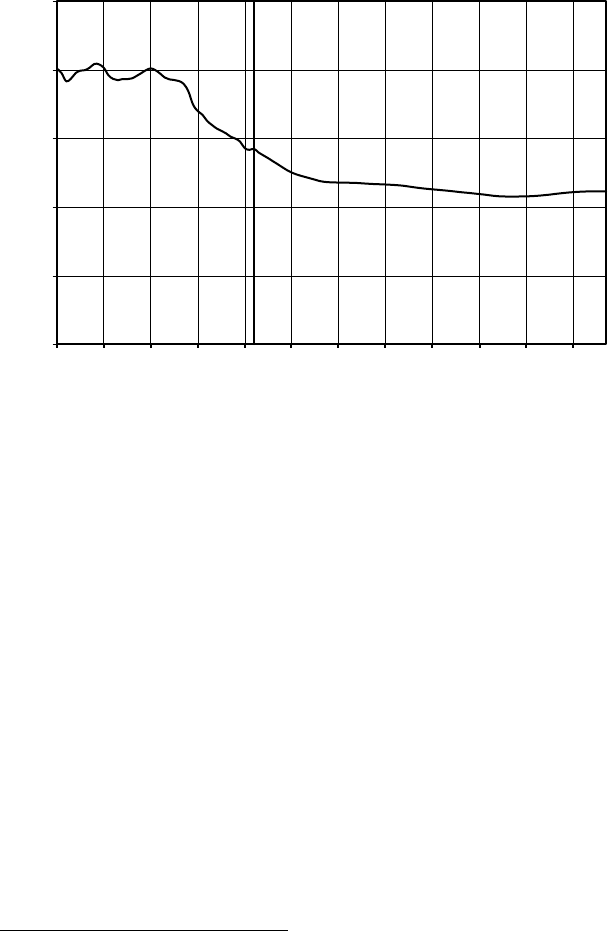

Figure I.1 shows Medicare’s projected expenditures as a percentage of

the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) under two sets of assumptions:

current law and an illustrative alternative, described below.

4

Figure I.1.—Medicare Expenditures as a Percentage

of the Gross Domestic Product under Current Law

and Illustrative Alternative Projections

Note: Percentages are affected by economic cycles.

The expenditure projections reflect the cost-reduction provisions

required under current law but not the payment reductions and/or

delays that would result from the HI trust fund depletion. In the year

of asset depletion, which is projected to be 2031 in this report, HI

revenues are projected to cover 89 percent of incurred program costs.

The illustrative alternative shown in the top line of figure I.1 assumes

that (i) there would be a transition from current-law

5

payment updates

4

A set of illustrative alternative Medicare projections has been prepared under a

hypothetical modification to current law. A summary of the projections under the

illustrative alternative is contained in section V.C of this report, and a more detailed

discussion is available at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/illustrative-alternative-

scenario-2023.pdf. Readers should not infer any endorsement of the policies represented

by the illustrative alternative by the Trustees, CMS, or the Office of the Actuary.

Section V.C also provides additional information on the uncertainties associated with

productivity adjustments to specific provider payment updates and the scheduled

physician payment updates.

5

Medicare’s annual payment rate updates for most categories of provider services would

be reduced below the increase in providers’ input prices by the growth in economy-wide

productivity (1.0 percent over the long range).

0%

2%

4%

6%

8%

10%

2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070 2080 2090

Calendar year

Current Law

Illustrative Alternative

Introduction

8

for providers affected by the economy-wide productivity adjustments to

payment updates that reflect adjustments for health care productivity;

(ii) the average physician payment updates would transition from

current law

6

to payment updates that reflect the Medicare Economic

Index; and (iii) the bonuses for qualified physicians in advanced

alternative payment models (advanced APMs), which are expected to

end after 2025, and the $500-million payments for physicians in the

merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), which are set to expire

after 2024, would both continue indefinitely. The difference between

the illustrative alternative and the current-law projections continues

to demonstrate that the long-range costs could be substantially higher

than shown throughout much of the report if the cost-reduction

measures prove problematic and new legislation scales them back.

As figure I.1 shows, Medicare’s costs under current law rise steadily

from their current level of 3.7 percent of GDP in 2022 to 6.0 percent in

2047. Costs then rise more slowly before leveling off at around

6.1 percent in the final 25 years of the projection period. Under the

illustrative alternative, projected costs would continue rising steadily

throughout the projection period, reaching 6.4 percent of GDP in 2047

and 8.3 percent in 2097.

As the preceding discussion explains, and as the substantial

differences between current-law and illustrative alternative

projections demonstrate, Medicare’s actual future costs are highly

uncertain for reasons apart from the inherent challenges in projecting

health care cost growth over time. The Board recommends that readers

interpret the current-law estimates in the report as the outcomes that

would be experienced under the Trustees’ economic and demographic

assumptions if the required cost-reduction provisions can be sustained

in the long range. Readers are encouraged to review section V.C for

further information on this important subject. The key financial

outcomes under the illustrative alternative scenario are shown with

the current-law projections throughout this report.

6

The law specifies physician payment rate updates of 0.75 percent or 0.25 percent

annually thereafter for physicians in advanced alternative payment models (advanced

APMs) or the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS), respectively. These updates

are notably lower than the projected physician cost increases, which are assumed to

average 2.05 percent per year in the long range.

9

II. OVERVIEW

A. HIGHLIGHTS

The major findings of this report under the intermediate set of

assumptions appear below. The balance of the Overview and the

following Actuarial Analysis section describe these findings in more

detail.

In 2022

In 2022, Medicare covered 65.0 million people: 57.1 million aged 65

and older, and 7.9 million disabled. About 46 percent of these

beneficiaries have chosen to enroll in Part C private health plans that

contract with Medicare to provide Part A and Part B health services.

Total expenditures in 2022 were $905.1 billion, and total income was

$988.6 billion, which consisted of $980.7 billion in non-interest income

and $7.9 billion in interest earnings. Assets held in special issue U.S.

Treasury securities increased by $83.4 billion to $409.1 billion. The

significant increase in assets was due to lower actual expenditures

than estimated in last year’s report.

Short-Range Results

The estimated depletion date for the HI trust fund is 2031, 3 years later

than projected in last year’s report. As in past years, the Trustees have

determined that the fund is not adequately financed over the next

10 years. HI income is projected to be higher than last year’s estimates

because both the number of covered workers and average wages are

projected to be higher. HI expenditures are projected to be lower than

last year’s estimates through the short-range period mainly as a result

of updated expectations for health care spending following the

COVID-19 pandemic, as described in section I.

In 2022, HI income exceeded expenditures by $53.9 billion. The

Trustees project deficits beginning in 2025 and continuing until the

trust fund becomes depleted in 2031. The assets were $196.6 billion at

the beginning of 2023, representing about 49 percent of expenditures

projected for 2023, which is below the Trustees’ minimum

recommended level of 100 percent. The HI trust fund has not met the

Trustees’ formal test of short-range financial adequacy since 2003.

Growth in HI expenditures has averaged 2.9 percent annually over the

last 5 years, compared with non-interest income growth of 6.1 percent.

Over the next 5 years, projected average annual growth rates for

expenditures and non-interest income are 8.9 percent and 5.0 percent,

respectively.

Overview

10

The SMI trust fund is expected to be adequately financed over the next

10 years and beyond because income from premiums and government

contributions for Parts B and D—which are contributions of the

Federal Government that the law authorizes to be appropriated and

transferred from the general fund of the Treasury—are reset each year

to cover expected costs and ensure a reserve for Part B contingencies.

The monthly Part B premium for 2023 is $164.90.

Part B and Part D costs have averaged annual growth rates of

6.8 percent and 4.7 percent, respectively, over the last 5 years, as

compared to growth of 5.5 percent for the Gross Domestic Product

(GDP). The Trustees project that cost growth over the next 5 years will

average 9.7 percent for Part B and 6.2 percent for Part D, faster than

the projected average annual GDP growth rate of 4.3 percent over the

period.

As required by law, the Trustees are issuing a determination of

projected excess general revenue Medicare funding in this report

because the difference between Medicare’s total outlays and its

dedicated financing sources

7

is projected to exceed 45 percent of outlays

within 7 years. Since this determination was made last year as well,

this year’s determination triggers a Medicare funding warning, which

(i) requires the President to submit to Congress proposed legislation to

respond to the warning within 15 days after the submission of the

Fiscal Year 2025 Budget and (ii) requires Congress to consider the

legislation on an expedited basis. This is the seventh consecutive year

that a determination of excess general revenue Medicare funding has

been issued, and the sixth consecutive year that a Medicare funding

warning has been issued.

Long-Range Results

For the 75-year projection period, the HI actuarial balance has

increased to −0.62 percent of taxable payroll from −0.70 percent in last

year’s report. (Under the illustrative alternative projections, the HI

actuarial balance would be −1.46 percent of taxable payroll.) Several

factors contributed to the change in the actuarial balance, most notably

lower-than-estimated 2022 expenditures (+0.19 percent); changes to

private health plan assumptions (+0.05 percent); and changes in

growth assumptions for skilled nursing, home health, and hospice care

(+0.03 percent). These improvements are partially offset by changes to

hospital assumptions (−0.07 percent); changes to economic and

7

Dedicated financing sources consist of HI payroll taxes, the HI share of income taxes on

Social Security benefits, Part D State payments, Part B drug fees, and beneficiary

premiums.

Highlights

11

demographic assumptions (−0.08 percent); lower-than-estimated 2022

incurred payroll tax income and income from the taxation of Social

Security benefits (−0.03 percent); and other minor changes

(−0.01 percent).

Part B outlays were 1.8 percent of GDP in 2022, and the Board projects

that they will grow to about 3.5 percent by 2097 under current law.

The long-range projections as a percent of GDP are lower than those

projected last year because of (i) lower projected spending on physician-

administered drugs resulting from the price negotiation provisions of

the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 (IRA) and (ii) updated expectations

with regard to the pandemic recovery. (Part B costs in 2097 would be

4.6 percent under the illustrative alternative scenario.)

The Board estimates that Part D outlays will increase from 0.5 percent

of GDP in 2022 to about 0.7 percent by 2097. The long-range

expenditure projections as a percent of GDP are lower in the current

report largely due to the projected impact of drug price negotiations

and other price growth constraints included in the provisions of the

IRA.

Government contributions, which are transfers from the general fund

of the Treasury, and premium income constitute the vast majority of

SMI income. General fund transfers finance about three-quarters of

SMI costs and are central to the automatic financial balance of the

fund’s two accounts. Such transfers represent a large and growing

requirement for the Federal budget. SMI government contributions

were 1.7 percent of GDP in 2022 and are projected to increase to

approximately 3.0 percent in 2097. (SMI government contributions in

2097 would be 3.8 percent under the illustrative alternative scenario.)

Conclusion

Total Medicare expenditures were $905 billion in 2022. The Trustees

project that expenditures will increase in future years at a faster pace

than either aggregate workers’ earnings or the economy overall and

that, as a percentage of GDP, spending will increase from 3.7 percent

in 2022 to 6.1 percent by 2097 (based on the Trustees’ intermediate set

of assumptions). Under the relatively higher price increases for

physicians and other health services assumed for the illustrative

alternative projection, Medicare spending would represent roughly

8.3 percent of GDP in 2097. Growth under either of these scenarios

would substantially increase the strain on the nation’s workers, the

economy, Medicare beneficiaries, and the Federal budget.

Overview

12

The Trustees project that HI tax income and other non-interest income

will fall short of HI incurred expenditures beginning in 2025. The HI

trust fund does not meet either the Trustees’ test of short-range

financial adequacy or their test of long-range close actuarial balance.

The Part B and Part D accounts in the SMI trust fund are expected to

be adequately financed because income from premiums and

government contributions are reset each year to cover expected costs.

Such financing, however, would have to increase faster than the

economy to cover expected expenditure growth.

The financial projections in this report indicate a need for substantial

changes to address Medicare’s financial challenges. The sooner

solutions are enacted, the more flexible and gradual they can be. The

early introduction of reforms increases the time available for affected

individuals and organizations—including health care providers,

beneficiaries, and taxpayers—to adjust their expectations and

behavior. The Trustees recommend that Congress and the executive

branch work closely together to expeditiously address these challenges.

Medicare Data

13

B. MEDICARE DATA FOR CALENDAR YEAR 2022

HI (Part A) and SMI (Parts B and D) have separate trust funds, sources

of revenue, and categories of expenditures. Table II.B1 presents

Medicare data for calendar year 2022, in total and for each part of the

program. For additional information, see section III.B for HI and

sections III.C and III.D for SMI.

For fee-for-service Medicare, the largest category of Part A

expenditures is inpatient hospital services, while the largest Part B

expenditure category is physician services. Payments to private health

plans for providing Part A and Part B services represented roughly

52 percent of total A and B benefit outlays in 2022.

Table II.B1.—Medicare Data for Calendar Year 2022

SMI

HI or Part A

Part B

Part D

Total

Assets at end of 2021 (billions)

$142.7

$163.3

$19.7

$325.7

Total income

$396.6

$467.6

$124.3

$988.6

Payroll taxes

352.8

—

—

352.8

Interest

4.1

3.6

0.1

7.9

Taxation of benefits

32.8

—

—

32.8

Premiums

4.8

131.3

17.6

153.7

Government contributions

1.1

329.7

92.4

423.2

Payments from States

—

—

13.7

13.7

Other

1.0

2.9

0.5

4.5

Total expenditures

$342.7

$436.7

$125.7

$905.1

Benefits

337.4

431.6

125.2

894.2

Hospital

142.6

63.0

—

205.5

Skilled nursing facility

28.3

—

—

28.3

Home health care

5.9

10.2

—

16.1

Physician fee schedule services

—

73.4

—

73.4

Private health plans (Part C)

169.3

234.0

—

403.3

Prescription drugs

—

—

125.2

125.2

Other

1

−8.6

51.1

—

42.4

Administrative expenses

5.3

5.1

0.5

11.0

Net change in assets

$53.9

$30.9

−$1.4

$83.4

Assets at end of 2022

$196.6

$194.2

$18.3

$409.1

Enrollment (millions)

Aged

56.7

52.2

44.8

57.1

Disabled

7.9

7.3

6.6

7.9

Total

64.7

59.5

51.4

65.0

Average benefit per enrollee

1

$5,217

$7,255

$2,437

$14,908

1

Includes repayments of $33.4 billion and $17.4 billion to Part A and Part B, respectively, for the Medicare

Accelerated and Advance Payments Program.

Note: Totals do not necessarily equal the sums of rounded components.

For HI, the primary source of financing is the payroll tax on covered

earnings. Employers and employees each pay 1.45 percent of a

worker’s wages, while self-employed workers pay 2.9 percent of their

net earnings. Starting in 2013, high-income workers pay an additional

0.9-percent tax on their earnings above an unindexed threshold

($200,000 for single taxpayers and $250,000 for married couples).

Overview

14

Other HI revenue sources include a portion of the Federal income taxes

that Social Security recipients with incomes above certain unindexed

thresholds pay on their benefits, as well as interest earned on the

securities held in the HI trust fund.

For SMI, transfers from the general fund of the Treasury represent the

largest source of income. The transfers covered about 75 percent of

program costs in 2022. Also, beneficiaries pay monthly premiums for

Parts B and D that finance a portion of the total cost. As with HI, the

securities held in the SMI trust fund earn interest.

Medicare Assumptions

15

C. MEDICARE ASSUMPTIONS

Future Medicare expenditures will depend on a number of factors,

including the size and composition of the population eligible for

benefits, changes in the volume and intensity of services, and increases

in the price per service. Future HI trust fund income will depend on

the size of the covered work force and the level of workers’ earnings,

and future SMI trust fund income will depend on projected program

costs. These factors will depend in turn upon future birth rates, death

rates, labor force participation rates, wage increases, and many other

economic and demographic factors affecting Medicare. To illustrate the

uncertainty and sensitivity inherent in estimates of future Medicare

trust fund operations, the Board has prepared current-law projections

under a low-cost and a high-cost set of economic and demographic

assumptions as well as under an intermediate set. In addition, the

Trustees asked the CMS Office of the Actuary to develop the

illustrative alternative projections to demonstrate the potential effect

on the Medicare financial status if certain current-law features are not

fully implemented in the future.

Table II.C1 summarizes the key assumptions used in this report. Many

of the demographic and economic variables that determine Medicare

costs and income are common to the Old-Age, Survivors, and Disability

Insurance (OASDI) program, and the OASDI annual report explains

these variables in detail. These variables include changes in the

Consumer Price Index (CPI) and wages, real interest rates, fertility

rates, mortality rates, and net immigration levels. (Real indicates that

the effects of inflation have been removed.) The assumptions vary, in

most cases, from year to year during the first 5 to 25 years before

reaching the ultimate values

8

assumed for the remainder of the 75-year

projection period.

8

The assumptions do not include economic cycles beyond the first 10 years.

Overview

16

Table II.C1.—Key Assumptions, 2047–2097

Intermediate

Low-Cost

High-Cost

Economic:

Annual percentage change in:

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita

1

..............

3.7

4.8

2.5

Average wage in covered employment .....................

3.56

4.79

2.35

Private nonfarm business total factor productivity

2

...

1.0

—

—

Consumer Price Index (CPI) .....................................

2.4

3.0

1.8

Real-wage growth (percent) ..........................................

1.14

1.74

0.54

Real interest rate (percent) ...........................................

2.3

2.8

1.8

Demographic:

Total fertility rate (children per woman).........................

1.99

2.19

1.69

Annual percentage reduction in total

age-sex adjusted death rates ....................................

0.74

0.28

1.24

Net lawful permanent resident (LPR) immigration ........

788,000

1,000,000

595,000

Net other-than-LPR immigration ...................................

457,000

683,000

234,000

Health cost growth:

Annual percentage change in per beneficiary

Medicare expenditures (excluding demographic

impacts)

1

HI (Part A) ..................................................................

3.5

3

3

SMI Part B .................................................................

3.7

3

3

SMI Part D .................................................................

4.0

3

3

Total Medicare ...........................................................

3.7

3

3

1

The assumed ultimate increases in per capita GDP and per beneficiary Medicare expenditures can also

be expressed in real terms, adjusted to remove the impact of assumed inflation. When adjusted by the

chain-weighted GDP price index, assumed real per capita GDP growth under the intermediate

assumptions is 1.7 percent, and real per beneficiary Medicare cost growth is 1.4 percent, 1.6 percent, and

1.9 percent for Parts A, B, and D, respectively.

2

Private nonfarm business total factor productivity is published by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and is

used as the economy-wide private nonfarm business total factor productivity to adjust certain provider

payment updates.

3

See section III.B3 for further explanation of the Part A alternative (low-cost and high-cost) assumptions.

Long-range alternative projections are not prepared for Parts B and D.

Other assumptions are specific to Medicare. As with all of the

assumptions underlying the financial projections, the Trustees review

the Medicare-specific assumptions annually and update them based on

the latest available data and analysis of trends. In addition, the

assumptions and projection methodology are subject to periodic review

by independent panels of expert actuaries and economists. The most

recent completed review occurred with the 2016–2017 Technical

Review Panel on the Medicare Trustees Report.

9

Section IV.D describes the methodology used to derive the long-range

Medicare cost growth assumptions,

10

which reflect the annual percent

change in per beneficiary Medicare expenditures (excluding

demographic effects), for the following five categories of provider

services:

9

The Panel’s final report is available at https://aspe.hhs.gov/system/files/pdf/257821/

MedicareTechPanelFinalReport2017.pdf.

10

When Medicare cost growth rates are compared to the per capita increase in GDP, they

are characterized as GDP plus X percent.

Medicare Assumptions

17

(i) All HI, and some SMI Part B, services that are updated annually

by provider input price increases less the increase in economy-wide

productivity.

HI services are inpatient hospital, skilled nursing facility, home

health, and hospice. The primary Part B services affected are

outpatient hospital, home health, and dialysis. Under the

Trustees’ intermediate economic assumptions, the year-by-year

cost growth rates for these provider services start at 3.7 percent

in 2047, or GDP plus 0.1 percent, declining gradually to

3.4 percent in 2097, or GDP minus 0.3 percent.

(ii) Physician services

Payment rate updates are 0.75 percent per year for those qualified

physicians assumed to be participating in advanced alternative

payment models (advanced APMs) and 0.25 percent for those

assumed to be participating in the merit-based incentive payment

system (MIPS). The year-by-year cost growth rates for physician

payments are assumed to decline from 3.3 percent in 2047, or

GDP minus 0.3 percent, to 2.9 percent in 2097, or GDP minus

0.8 percent.

(iii) Certain SMI Part B services that are updated annually by the CPI

increase less the increase in productivity.

Such services include durable medical equipment that is not

subject to competitive bidding,

11

care at ambulatory surgical

centers, ambulance services, and medical supplies. The Trustees

assume the year-by-year cost growth rates for these services to

decline from 2.9 percent in 2047, or GDP minus 0.7 percent, to

2.6 percent in 2097, or GDP minus 1.1 percent.

(iv) The remaining Part B services, which consist mostly of physician-

administered drugs, laboratory tests, and small facility services.

Payments for these Part B services, which constitute an estimated

33 percent of total Part B expenditures in 2032, are established

through market processes and are not affected by the productivity

adjustments. For physician-administered Part B drugs, the key

inflation provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) are not

anticipated to affect such payments over the long range. The long-

11

The portion of durable medical equipment that is subject to competitive bidding is

included with all other Medicare services since the price is determined by a competitive

bidding process. For more information on the bidding process, see section IV.B.

Overview

18

range cost growth rates for these services are assumed to equal

the growth rates as determined from the “factors contributing to

growth” model. The corresponding year-by-year cost growth rates

decline from 4.4 percent in 2047, or GDP plus 0.8 percent, to

4.1 percent by 2097, or GDP plus 0.4 percent.

(v) Prescription drugs provided through Part D.

Medicare payments to Part D plans are based on a competitive-

bidding process but are influenced by key provisions in the IRA

linking drug price growth to the rate of overall inflation. As a

result, they are assumed to grow over the long range slightly more

slowly than would be the case if they were determined strictly

through market processes. The corresponding year-by-year cost

growth rates decline from 4.2 percent in 2047, or GDP plus

0.6 percent, to 3.9 percent by 2097, or GDP plus 0.2 percent.

After combining the rates of growth from the four long-range

assumptions, the weighted average cost growth rate for Part B is

3.8 percent in 2047, or GDP plus 0.2 percent, declining to 3.7 percent

by 2097, or GDP plus 0.0 percent. When Parts A, B, and D are

combined, the weighted average cost growth rate for Medicare is

3.8 percent, or GDP plus 0.2 percent in 2047, declining to 3.6 percent,

or GDP minus 0.1 percent by 2097.

In addition, these cost growth rates must be modified to account for

demographic impacts, which reflect the changing distribution of the

Medicare population by age, sex, and time-to-death.

12

Those who are

closer to death have higher health spending, regardless of age. The

Trustees assume that as mortality rates for Medicare beneficiaries

continue to improve in the future, a smaller portion of the population

will be closer to death at a given age, which somewhat offsets the effect

of individuals getting older and spending more on health care. This is

particularly the case for Part A services—such as inpatient hospital,

skilled nursing, and home health services—for which the distribution

of spending is more concentrated in the period right before death. For

Part B services and Part D, the incorporation of the time-to-death

adjustment has a smaller effect.

As in the past, the Trustees establish detailed growth rate assumptions

for the initial 10 years (2023 through 2032) by individual type of

service (for example, inpatient hospital care and physician services).

12

More information on the time-to-death adjustment is available at

https://www.cms.gov/files/document/incorporation-time-death-medicare-demographic-

assumptions.pdf.

Medicare Assumptions

19

These assumptions reflect recent trends and the impact of all

applicable statutory provisions. For each of Parts A, B, and D, the

assumed cost growth rates for years 11 through 25 of the projection

period (adjusted to reflect discontinuities in yearly payment policies)

are set by interpolating between the rate at the end of the short-range

projection period and the rate at the start of the last 50 years of the

long-range period described above. The 2016–2017 Medicare Technical

Review Panel concluded that both the current length of the transition

period and the current approach to the transition are reasonable, and

they recommended that the Trustees continue to use the same

approach to transition between short-range and long-range projections

for both HI and SMI.

13

The basis for the Medicare cost growth rate assumptions, described

above, has been chosen primarily to incorporate the productivity

adjustments and the physician payment structure in a relatively

simple, straightforward manner and with the assumption that these

elements of current law will operate in all future years as specified.

The Trustees use this approach in part due to the uncertainty

associated with these provisions and in part due to the difficulty of

modeling such consequences as access to care, health status, and

utilization if these provisions of current law do not operate as

intended.

14

They have incorporated the effects of changes in payment

mechanisms, delivery systems, and other aspects of health care that

have been implemented recently, including modest savings from

accountable care organizations. However, they have not considered the

possible effects of future changes that could arise in response to the

payment limitations or future innovative payment models, nor have

they taken into account the potential effects of sustained slower

payment increases on provider participation, beneficiary access to care,

quality of services, and other factors.

15

Consistent with the practice in recent reports, a set of illustrative

alternative Medicare projections has been developed. This information

is presented in section V.C. An actuarial memorandum on the

illustrative alternative is available on the CMS website.

16

The

illustrative alternative projection assumes that (i) there would be a

transition from current-law payment updates for providers affected by

the economy-wide productivity adjustments to payment updates that

13

See Findings 6-2 and 6-3 and Recommendation 6-1.

14

For a detailed discussion of uncertainty, see section V.C.

15

The 2016–2017 Medicare Technical Review Panel considered these issues at some

length. Their final report contains a discussion of the delivery system changes to date

and the impact on the Medicare projections.

16

See https://www.cms.gov/files/document/illustrative-alternative-scenario-2023.pdf.

Overview

20

reflect adjustments for health care productivity; (ii) the average

physician payment updates would transition from current law to

payment updates that reflect the Medicare Economic Index; and

(iii) the bonuses for qualified physicians in advanced APMs, which are

expected to end after 2025, and the $500-million payments for

physicians in MIPS, which are set to expire after 2024, would both

continue indefinitely. The transition from current law to the ultimate

illustrative alternative assumptions starts at the same dates that were

assumed in last year’s report. The year-by-year cost growth rate

assumptions for HI and SMI Part B under the illustrative alternative

projections decline from approximately 4.4 percent in 2047, or GDP

plus 0.8 percent, to 4.1 percent by 2097, or GDP plus 0.4 percent. On

average over this period, the growth rate of per beneficiary

expenditures for these services is equal to the growth rate for per

capita national health expenditures, as described previously (in the

fourth category of provider services) for other Medicare services for

which price updates are based on market processes.

For the HI low-cost and high-cost projections, Medicare expenditures

are determined by changing the assumption for the ratio of aggregate

costs to taxable payroll (the cost rate). These changes are intended to

provide an indication of how Medicare expenditures could vary in the

future as a result of different economic, demographic, and health care

trends.

17

For the HI high-cost assumptions, the assumed annual

increase in the cost rate during the initial 25-year period is

2 percentage points greater than under the intermediate assumptions.

Under the low-cost assumptions, the assumed annual rate of increase

in the cost rate for the initial period is 2 percentage points less than

under the intermediate assumptions. The Trustees assume that, after

25 years, the 2-percentage-point differentials will decline gradually to

zero in 2072, after which the growth in cost rates is the same under all

three sets of assumptions.

While it is possible that actual economic, demographic, and health cost-

growth experience will fall within the range defined by the three

alternative sets of assumptions, there can be no assurances that it will

do so in light of the wide variations in these factors over past decades.

In general, readers can place a greater degree of confidence in the

assumptions and estimates for the earlier years than for the later

years. Nonetheless, even for the earlier years, the estimates are only

an indication of the expected trends and the general ranges of future

17

Under the automatic financing provisions for the SMI programs, Parts B and D will be

adequately financed. Accordingly, the Trustees have not conducted high-cost and

low-cost analyses of the general fund transfers.

Medicare Assumptions

21

Medicare experience. Also, as a result of the uncertain long-range

adequacy of physician payments and payments affected by the

statutory productivity adjustments, actual future Medicare

expenditures could exceed the intermediate projections shown in this

report, possibly by large amounts. Reference to key results under the

illustrative alternative projection demonstrates this potential

understatement.

Overview

22

D. FINANCIAL OUTLOOK FOR THE MEDICARE PROGRAM

This report evaluates the financial status of the HI and SMI trust

funds. For HI, the Trustees apply formal tests of financial status for

both the short range and the long range; for SMI, the Trustees assess

the ability of the trust fund to meet incurred costs over the period for

which financing has been set.

HI and SMI are financed in very different ways. Within SMI, current

law provides for the annual determination of Part B and Part D

beneficiary premiums and government contributions to cover expected

costs for the following year. In contrast, HI is subject to substantially

greater variation in asset growth, since employee and employer tax

rates under current law do not change or adjust to meet expenditures

except through new legislation.

Despite the significant differences in benefit provisions and financing,

the two components of Medicare are closely related. HI and SMI

operate in an interdependent health care system. Most Medicare

beneficiaries are enrolled in HI and SMI Parts B and D, and many

receive services from all three. Accordingly, efforts to improve and

reform either component must necessarily have repercussions for the

other component. In view of the anticipated growth in Medicare

expenditures, it is also important to consider the distribution among

the various sources of revenues for financing Medicare and the manner

in which this distribution will change over time.

This section reviews the projected total expenditures for the Medicare

program, along with the primary sources of financing. Figure II.D1

shows projected costs as a percentage of GDP. Medicare expenditures

represented 3.7 percent of GDP in 2022. Under current law, costs

increase to 6.0 percent of GDP by 2047, largely due to the rapid growth

in the number of beneficiaries, and then to 6.1 percent of GDP in 2097,

with growth in health care cost per beneficiary becoming the larger

factor later in the valuation period, particularly for Part D costs, which

are not affected by legislated price reductions. (If the payment update

constraints were phased down as in the illustrative alternative

projections, then Medicare expenditures would reach an estimated

8.3 percent of GDP in 2097.)

Medicare Financial Outlook

23

Figure II.D1.—Medicare Expenditures as a Percentage

of the Gross Domestic Product

Note: Percentages are affected by economic cycles.

Table II.D1 shows five components of Medicare expenditure growth

over three valuation periods: (i) growth of overall prices as measured

by the CPI; (ii) growth of Medicare prices relative to growth in the CPI;

(iii) growth in the number of beneficiaries; (iv) change in the

demographic composition of the beneficiaries; and (v) change in the

volume and intensity of services. The price growth for Part A is

projected to be below CPI growth initially, close to CPI growth in the

2033–2047 period, and below in the long run, and for Part B it is

projected to be below CPI growth during each of the three valuation

periods. As discussed in section IV.D, prices for all of Part A and some

of Part B are constrained by the payment updates specified under

current law, and Part B prices are further constrained by the current-

law physician payment updates. For all parts of Medicare, growth in

the number of beneficiaries is highest over the next 10 years, as the

baby boom generation continues to enter Medicare, and slows

continually thereafter.

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

2000 2010 2020 2030 2040 2050 2060 2070 2080 2090

Calendar year

Total

HI

Part B

Part D

Overview

24

Table II.D1.—Components of Increase in Medicare Incurred Expenditures by Part

[In percent]

Average annual percentage change

Prices

Valuation

period

CPI

Medicare

relative to

CPI

Overall

Medicare

Number of

beneficiaries

Beneficiary

demographic

mix

Volume and

intensity

Total

increase

Part A:

2023–2032

3.2 %

−0.2 %

3.0 %

1.9 %

0.1 %

1.8 %

7.0 %

2033–2047

2.4

0.1

2.5

0.6

0.4

1.3

4.8

2048–2097

2.4

−0.2

2.2

0.5

−0.1

1.3

3.9

Part B:

2023–2032

3.2

−1.1

2.0

2.0

0.1

4.2

8.5

2033–2047

2.4

−0.3

2.1

0.6

0.0

2.7

5.5

2048–2097

2.4

−0.2

2.2

0.5

−0.1

1.5

4.2

Part D:

2023–2032

3.2

1

1

2.4

−0.2

1

5.8

2033–2047

2.4

1

1

0.6

−0.2

1

4.3

2048–2097

2.4

1

1

0.5

−0.1

1

4.5

1

Volume and intensity and price components are not available for Part D due to the current methodology

used to incorporate the provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022.

Notes: 1. Price reflects annual updates, total factor productivity reductions, and any other reductions

required by law or regulation.

2. Volume and intensity is the residual after the other four factors shown in the table (CPI, excess

Medicare price, number of beneficiaries, and beneficiary demographic mix) are removed.

3. Totals do not necessarily equal the sums of rounded components.

Most beneficiaries have the option to enroll in private health insurance

plans that contract with Medicare to provide Part A and Part B medical

services. The share of Medicare beneficiaries in such plans has risen

rapidly in recent years; it reached 46 percent in 2022 from 12.8 percent

in 2004. Payments to Medicare Advantage plans are based on

benchmarks that range from 95 to 115 percent of local fee-for-service

Medicare costs, with bonus amounts payable for plans meeting high

quality-of-care standards. The Trustees project that the overall

participation rate for private health plans will continue to increase—

from about 49 percent in 2023 to about 56 percent in 2032 and

thereafter.

18

Figure II.D2 shows the past and projected amounts of Medicare

revenues under current law excluding interest income, which will not

be a significant part of program financing in the long range as trust

fund assets decline. The figure compares total Medicare expenditures

to Medicare non-interest income—from HI payroll taxes, HI income

from the taxation of Social Security benefits, HI and SMI premiums,

SMI Part D State payments for certain Medicaid beneficiaries, fees on

manufacturers and importers of brand-name prescription drugs

(allocated to Part B), and HI and SMI general fund transfers. The

18

For more detail on the Medicare Advantage program, see section IV.C.

Medicare Financial Outlook

25

Trustees expect total Medicare expenditures to exceed non-interest

revenue for all future years.

Figure II.D2.—Medicare Sources of Non-Interest Income and Expenditures

as a Percentage of the Gross Domestic Product

Note: Percentages are affected by economic cycles.

As shown in figure II.D2, for most of the historical period, payroll tax

revenues increased steadily as a percentage of GDP due to increases in

the HI payroll tax rate and in the limit on taxable earnings, the latter

of which lawmakers eliminated in 1994. Beginning in 2013, the HI

trust fund receives an additional 0.9-percent tax on earnings in excess

of a threshold amount.

19

The Trustees project that, as a result of this

provision, payroll taxes will grow slightly faster than GDP.

20

Beginning

in 2022, HI revenue from income taxes on Social Security benefits is

19

Current law also specifies that individuals with incomes greater than $200,000 per

year and couples above $250,000 pay an additional Medicare contribution of 3.8 percent

on some or all of their non-work income (such as investment earnings). However, the

revenues from this tax are not allocated to the Medicare trust funds.

20

Although the Trustees expect total worker compensation to grow at the same rate as

GDP after the first 10 years of the projection, wages and salaries are projected to increase

more slowly than fringe benefits (health insurance costs in particular). Thus, projected

taxable earnings (wages and salaries) gradually decline as a percentage of GDP. Absent

any change to the tax rate scheduled under current law, HI payroll tax revenue would

similarly decrease as a percentage of GDP. Over time, however, a growing proportion of

workers will have earnings that exceed the fixed earnings thresholds specified in the law

($200,000 and $250,000), and an increasing portion of taxable earnings will therefore

become subject to the additional 0.9-percent HI payroll tax. The net effect of these factors

is an increasing trend in payroll taxes as a percentage of GDP.

0%

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

6%

7%

1966 1976 1986 1996 2006 2016 2026 2036 2046 2056 2066 2076 2086 2096

Calendar year

Historical

Payroll taxes

Tax on OASDI benefits

Premiums

General revenue

transfers

Total expenditures

Deficit

State payments and drug fees

Estimated

Overview

26

expected to gradually increase as a share of GDP as the share of

benefits subject to such taxes increases.

21

The Trustees expect growth in SMI Part B and Part D premiums and

transfers from the general fund of the Treasury to continue to outpace

GDP growth and HI payroll tax growth in the future. This phenomenon

occurs primarily because SMI revenue increases at the same rate as

expenditures, whereas HI revenue does not. Accordingly, as the HI

sources of revenue become increasingly inadequate to cover HI costs,

SMI revenues will represent a growing share of total Medicare

revenues. Government contributions are projected to gradually

increase from 43 percent of Medicare financing in 2022 to about

49 percent in 2040, stabilizing thereafter. Growth in these

contributions as a share of GDP adds significantly to the Federal

budget pressures. SMI premiums will also increase at the same rate as

SMI expenditure growth, placing a growing burden on beneficiaries.

High-income beneficiaries have paid an income-related premium for

Part B since 2007 and for Part D since 2011.

The interrelationship between the Medicare program and the Federal

budget is an important topic—one that will become increasingly

critical over time as the general fund requirements for SMI continue to

grow. Transfers from the general fund of the Treasury are the major

source of financing for the SMI trust fund and are central to the

automatic financial balance of the fund’s two accounts, while

representing a large and growing requirement for the Federal budget.

SMI government contributions equaled 1.7 percent of GDP in 2022 and

will increase to an estimated 3.0 percent in 2097 under current law.

Moreover, in the absence of legislation to address the financial

imbalance, interest earnings on trust fund assets and redemption of

those assets will cover the difference between HI dedicated revenues

and expenditures until 2031.

22

In 2030, this funding shortfall for the

HI trust fund represents 0.2 percent of GDP. Section V.F describes the

interrelationship between the Federal budget and the Medicare and

Social Security trust funds; it illustrates the programs’ long-range

financial outlook from both a trust fund perspective and a budget

perspective.

Federal law requires that the Trustees issue a determination of excess

general revenue Medicare funding if they project that under current

21

See section V.C7 of the 2023 OASDI Trustees Report for more detailed information on

the projection of income from taxation of Social Security benefits.

22

After asset depletion in 2031, as described in section II.E, no provision exists to use

transfers from the general fund of the Treasury or any other means to cover the HI

deficit.

Medicare Financial Outlook

27

law the difference between program outlays and dedicated financing

sources

23

will exceed 45 percent of Medicare outlays within the first

7 fiscal years of the projection. For this year’s report, the difference

between program outlays and dedicated revenues is expected to exceed

45 percent in fiscal year 2025, and therefore the Trustees are issuing

this determination. (Section V.B contains additional details on these

tests.) Since this determination was made last year as well, this year’s

determination triggers a Medicare funding warning, which (i) requires

the President to submit to Congress proposed legislation to respond to

the warning within 15 days after the submission of the Fiscal

Year 2025 Budget and (ii) requires Congress to consider the legislation

on an expedited basis. Such funding warnings were previously issued

in each of the 2007 through 2013 reports and in the 2018 through 2022

reports.

This section has summarized the total financial obligation posed by

Medicare and the manner in which it is financed. However, the HI and

SMI components of Medicare have separate and distinct trust funds,

each with its own sources of revenues and mandated expenditures.

Accordingly, it is necessary to assess the financial status of each

Medicare trust fund separately. Sections II.E and II.F present such

assessments for the HI trust fund and the SMI trust fund, respectively.

23

The dedicated financing sources are HI payroll taxes, the HI share of income taxes on

Social Security benefits, Part B receipts from the fees on manufacturers and importers

of brand-name prescription drugs, Part D State payments, and beneficiary premiums.

These sources are the first four layers depicted in figure II.D2.

Overview

28

E. FINANCIAL STATUS OF THE HI TRUST FUND

1. 10-Year Actuarial Estimates (2023–2032)

Expenditures from the HI trust fund exceeded income each year from

2008 through 2015. In 2016 and 2017, however, there were fund

surpluses amounting to $5.4 billion and $2.8 billion, respectively. In

2018, 2019, and 2020, expenditures again exceeded income, with trust

fund deficits of $1.6 billion, $5.8 billion, and $60.4 billion, respectively.

The large deficit in 2020 was mostly due to accelerated and advance

payments to providers from the trust fund. In 2021, there was a small

surplus of $8.5 billion as these payments began to be repaid to the trust

fund, and this continued repayment resulted in a larger surplus in

2022 of $53.9 billion. Deficits are projected to return beginning in 2025

and to persist for the remainder of the projection period, requiring

redemption of trust fund assets until the trust fund’s depletion in 2031.

Table II.E1 presents the projected operations of the HI trust fund

under the intermediate assumptions for the next decade. At the

beginning of 2023, HI assets represented 49 percent of annual

expenditures. This ratio has declined from 150 percent since 2007. The

Board has recommended an asset level at least equal to annual

expenditures, to serve as an adequate contingency reserve in the event

of adverse economic or other conditions.

The Trustees apply an explicit test of short-range financial adequacy,

described in section III.B2 of this report. Based on the 10-year

projection shown in table II.E1, the HI trust fund does not meet this

test because estimated assets are below 100 percent of annual

expenditures and are not projected to attain this level under the

intermediate assumptions. This outlook indicates the need for prompt

legislative action to achieve financial adequacy for the HI trust fund

throughout the short-range period.

HI Financial Outlook

29

Table II.E1.—Estimated Operations of the HI Trust Fund

under Intermediate Assumptions, Calendar Years 2022–2032

[Dollar amounts in billions]

Calendar year

Total income

1

Total

expenditures

Change in

fund

Fund at year end

Ratio of assets to

expenditures

2

2022

3

$396.6

$342.7

4

$53.9

$196.6

42%

2023

406.9

401.8

4

5.1

201.7

49

2024

427.1

421.9

5.2

206.8

48

2025

452.5

453.0

−0.5

206.3

46

2026

479.7

487.3

−7.6

198.7

42

2027

508.0

524.7

−16.7

181.9

38

2028

533.4

563.9

−30.5

151.4

32

2029

559.1

606.6

−47.5

103.9

25

2030

584.9

648.0

−63.1

40.8

16

2031

5

612.1

691.5

−79.3

−38.5

6

2032

5

639.3

737.3

−97.9

−136.5

6

1

Includes interest income.

2

Ratio of assets in the fund at the beginning of the year to expenditures during the year.

3

Figures for 2022 represent actual experience.

4

Includes net repayments of $33.4 billion and $1.1 billion in calendar years 2022 and 2023, respectively,

for the Medicare Accelerated and Advance Payments Program.

5

Estimates for 2031 and later are hypothetical since the HI trust fund would be depleted in those years.

6

Trust fund reserves would be depleted at the beginning of this year.

Note: Totals do not necessarily equal the sums of rounded components.

The short-range financial outlook for the HI trust fund is more

favorable than the projections in last year’s annual report. HI income

is projected to be higher throughout the projection period because both

the number of covered workers and average wages are projected to be

higher. HI expenditures are projected to be lower through the short-

range period mainly as a result of updated expectations for health care

spending following the COVID-19 pandemic, as described in section I.

Under the intermediate assumptions, after 2023 the assets of the HI

trust fund would steadily decrease as a percentage of annual

expenditures throughout the remainder of the short-range projection

period, as illustrated in figure II.E1. The ratio declines until the fund

is depleted in 2031, 3 years later than projected last year. If assets were

depleted, Medicare could pay health plans and providers of Part A

services only to the extent allowed by ongoing tax revenues—and these

revenues would be inadequate to fully cover costs. Beneficiary access