Business and Legal Issues for

Video Game Developers

A Training Tool

By David Greenspan and Gaetano Dimita

Contributions from S. Gregory Boyd and Andrea Rizzi

DISCLAIMER

The book is designed to help readers with a general understanding

of some of the legal and business issues in the video game industry

and does not constitute legal or any other professional advice. This

book is intended for educational and informational purposes only

and is not a substitute for legal advice from an attorney.

Reasonable efforts were used to base information on reliable

sources for the book, but the authors and publisher cannot assume

responsibility for their validity and consequences of their use.

NOTES ACCESSED

All websites were accessed between September 1, 2021, through

December 27, 2021.

DOI 10.34667/tind.45851

1 Mastering The Game

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 12

ABOUT THE AUTHORS 15

CHAPTER 1 THE GLOBAL STRUCTURE OF THE VIDEO GAME

INDUSTRY 17

1.1 – The Current Video Game Industry Landscape: The Numbers Behind

The Industry 17

1.2 – Demographics 22

1.3 – Geographic Breakdown 23

1.3.1 – The Major Revenue-Generating Countries 23

1.3.2 – Regional Markets 25

1.4 – Current State Of The Video Game Industry: The Players 26

1.4.1 – Game Distribution: The Platforms 27

1.4.2 – Console Manufacturers And Various Platforms 28

1.4.3 – Mobile Gaming 30

1.5 – Distribution: Digital, Retail And Cloud 31

1.5.1 – Digital Distribution 31

1.5.2 – Retail 33

1.5.3 – Cloud Gaming 33

1.6 – Major Players 35

1.6.1 – First Party 35

Microsoft 35

Nintendo 36

Sony 36

Valve 36

1.6.2 – Publishers 37

1.6.3 – Major Mobile Publishers 38

Mastering The Game

2

1.7 – Beyond The Game: Growing Areas In The Industry 40

1.7.1 – Monetization Models: The Impact Of Free-To-Play And The

Growth Of Live Services 40

1.7.2 – Video Games And Community 42

1.7.3 – Intellectual Property Issues In Streaming 44

1.7.4 – Esports 46

1.7.5 – Artificial Intelligence 50

1.7.6 – Immersive Technologies 50

1.8 – Legal Challenges 53

1.8.1 – Intellectual Property (IP) 54

1.8.2 – Monetization 55

1.8.3 – Privacy 55

1.8.4 – Labor Issues 56

1.8.5 – Antitrust Concerns 56

CHAPTER 2 INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY IN THE VIDEO GAME

INDUSTRY 58

2.1 – The Importance Of Intellectual Property 58

2.2 – Copyright 60

2.2.1 – What Can Be Protected By Copyright? 61

2.2.2 – What Rights Are Conferred By Copyright? 64

2.2.3 – Some Examples Of Copyright 65

2.2.4 – US Copyright Filing Information 66

2.2.5 – Term Of Protection 67

2.2.6 – Protecting Copyright 68

2.2.7 – Penalties For Infringement 69

2.2.8 – Derivative Works 70

2.2.9 – The Public Domain 72

2.2.10 – US Scènes à Faire Doctrine 75

2.2.11 – US Fair Use 75

2.2.12 – EU Copyright Exceptions And Limitations 76

2.2.13 – Moral Rights 78

2.2.14 – Copyright Ownership, Licenses And Chain of Title 78

3 Mastering The Game

2.2.15 – Common Questions About Copyright 79

2.3 – Trademark 80

2.3.1 – What Can Be Trademarked? 81

2.3.2 – Is It Necessary To Register A Trademark? 82

2.3.3 – Picking A Good Trademark 82

2.3.4 – Examples Of Trademarks 84

2.3.5 – Term Of Protection 86

2.3.6 – Registration Process And Cost In The United States 86

2.3.7 – Registration Process And Cost In The EU 87

2.3.8 – Madrid System For The International Registration Of Marks 87

2.3.9 – Protecting Trademarks In The United States 88

2.3.10 – Penalties For Infringement 89

2.3.11 – Unfair Competition 90

2.3.12 – Common Questions About Trademarks 91

Do I Have To Use A Trademark In Commerce? 91

Can I Let Fans Use My Trademark Without A Formal License? 92

Can I Trademark My Game Title? 92

2.4 – Patents 93

2.4.1 – What Can Be Patented? 94

2.4.2 – What Rights Are Conferred By Patents? 95

2.4.3 – Term Of Protection 95

2.4.4 – Process And Cost In The United States 95

2.4.5 – Process And Cost Outside The United States 97

2.4.6 – Protecting Patents 98

2.4.7 – Patent Litigation And Penalties For Infringing Patents 98

2.4.8 – US Patent Pending And Provisional Patent Applications 98

2.4.9 – Patent Invalidity 99

2.4.10 – Anticipation And Obviousness 99

2.4.11 – Timing A Patent Filing 100

2.4.12 – Reasons To File A Patent Application 100

2.4.13 – The European Patent System 101

2.4.14 – Video Game Patents In Europe 102

Mastering The Game

4

2.4.15 – Common Questions About Patents 104

What Can Our Company Put “Patent Pending” On? 104

Patent Agents And Patent Attorneys In The United States: What Is The

Difference? 105

2.5 – Rights Of Publicity 105

2.5.1 – Rights Of Publicity In The United States 106

2.5.2 – Rights Of Publicity In Other Countries 111

2.5.3 – Image Rights In Europe 111

United Kingdom 112

Germany 112

France 113

Italy 113

2.5.4 – Negotiating The Right Of Publicity 114

2.6 – Trade Secret 115

2.6.1 – What Can Be A Trade Secret? 116

2.6.2 – What Rights Are Conferred By Trade Secrets? 117

2.6.3 – Examples Of Trade Secrets 118

2.6.4 – Term Of Protection 118

2.6.5 – Process And Cost 118

2.6.6 – Protecting Trade Secrets 119

2.6.7 – Penalties For Infringement 119

2.6.8 – Common Questions About Trade Secrets 120

Can Trade Secret Status Help Me Protect My IP From Reverse

Engineering? 120

At What Stage Should A Game Company Use Trade Secrets? 120

2.7 – IP Strategy 101 121

Have A Relationship With Experienced IP Counsel 121

Protect IP In Advance 121

Protecting IP: Pitching A Game To Publishers And Investors 122

The Process Is Complex, But Results Are Achievable 122

Strategies For Small Companies And Individual Developers 122

Strategies For Large Developers And Publishers 123

5 Mastering The Game

2.8 – Three Important Points 123

CHAPTER 3 PUBLISHING A VIDEO GAME 125

3.1 – The Role Of The Publisher 125

3.1.1 – The Developer’s Concerns When Considering A Publisher 127

3.1.2 – The Publisher’s Concerns When Considering A Developer 128

3.1.3 – Going Independent 129

3.2 – The Publishing Agreement 130

3.2.1 – Introduction: The Long-Form Agreement 130

3.2.2 – Ownership Issues 131

3.2.3 – Rights Granted 133

3.2.4 – Additional Rights Issues: Right Of First Negotiation And Last

Refusal On Future Games 134

3.2.5 – Territory 136

3.2.6 – Term 137

3.2.7 – Developer’s Services; Delivery 139

Console Development Process 143

3.2.8 – Financials 143

3.2.9 – Revenue Share Involving Distribution Only 147

3.2.10 – Additional Royalty Issues And Payments 149

3.2.11 – Accounting And Statements 150

3.2.12 – Audit Rights 152

Parameters For Audits 152

Contesting A Statement 153

Cost Of Audits 154

3.2.13 – Publisher Commitments 154

3.2.14 – Representations And Warranties 156

3.2.15 – Indemnification 159

3.2.16 – Insurance 162

3.2.17 – Credits 164

3.2.18 – Termination For Cause 166

3.2.19 – Termination For Convenience 168

3.2.20 – Governing Law And Jurisdiction 169

Mastering The Game

6

3.2.21 – Dispute Resolution 170

3.2.22 – Additional Provisions 171

3.3 – A Changing Role 171

3.4 – Scenarios 172

CHAPTER 4 LICENSING CONTENT 179

4.1 – Introduction 179

4.2 – The Licensing Agreement: The Long-Form Agreement 185

4.3 – The Major Issues In Licensing Agreements 186

4.3.1 – Rights 186

4.3.2 – The Licensed Property 186

Sports Licensing 189

4.3.3 – Rights Granted 190

4.3.4 – Crossover Integration 192

4.3.5 – Platforms 193

4.3.6 – Territory And Term 195

4.3.7 – Licensing Fee 197

4.3.8 – Statements And Audits 200

4.3.9 – Ownership Issues 202

4.3.10 – Representations And Warranties 203

4.3.11 – Indemnification 206

4.3.12 – Approvals 208

4.3.13 – Termination Rights 210

4.3.14 – Expiration Of The Agreement 214

4.3.15 – Miscellaneous Provisions 214

4.4 – Music 215

4.4.1 – Hiring A Composer 216

4.4.2 – Licensing Music: Master And Synchronization Rights 218

4.4.3 – Music Libraries 221

4.4.4 – Public Domain Music 222

4.4.5 – New Opportunities: Virtual Concerts And Live Performances 222

4.4.6 – Anticipating Costs And Time 223

7 Mastering The Game

4.5 – Licensing Out IP 224

Film Options 226

4.5.1 – Licensing Agents 227

4.6 – Product Placement: A Different Form Of Licensing 231

CHAPTER 5 ACTOR-TALENT AGREEMENTS 235

5.1 – Introduction 235

5.2 – Who Negotiates The Deal? 235

5.3 – The Most Common Terms In The Agreement 238

5.3.1 – Services And Rights 238

5.3.2 – Ownership 240

5.3.3 – Compensation And Credit 240

5.3.4 – Conduct 242

5.3.5 – Approvals 242

5.3.6 – Termination 243

5.4 – SAG-AFTRA: A Closer Look 244

5.5 – The Growing Role Of Actors And The Importance Of The Actors

Unions 246

CHAPTER 6 VENDOR AGREEMENTS – INDEPENDENT

CONTRACTORS 248

CHAPTER 7 CONSOLES 254

7.1 – Introduction 254

7.2 – Agreements: Development And Hardware Tools 255

7.2.1 – Development and Hardware Tools 257

7.3 – Development, Manufacturing, And Distribution Issues 257

7.3.1 – The Submission And Approval Process 257

7.3.2 – Distribution 259

7.4 – Business Issues 260

7.4.1 – Minimum Order Requirement For Packaged Goods 260

7.4.2 – Licensing Platform Royalties 260

Mastering The Game

8

7.4.3 – Marketing 261

7.4.4 – Exclusivity 262

7.5 – Legal Issues 262

7.5.1 – Representations And Warranties, Indemnification, Limitation On

Liability 262

7.5.2 – Confidentiality 264

7.5.3 – Assignment 264

7.5.4 – Term And Termination 265

7.5.5- Choice Of Law, Venue 266

7.6 – Moving Forward 266

CHAPTER 8 PC DIGITAL DISTRIBUTION 267

8.1 – Introduction 267

8.2 – The Long Form PC Digital Agreement: Introduction 272

8.2.1 – Rights Granted 272

8.2.2 – Delivery Of Materials 274

8.2.3 – Continuing Obligations 274

8.2.4 – Term 275

8.2.5 – Marketing Issues 276

8.2.6 – Revenue Share And Pricing 277

8.2.7 – Statements And Audits 278

8.2.8 – Termination 279

8.2.9 – Limitation Of Liability 281

8.2.10 – Assignment 281

8.2.11 – Other Terms 282

CHAPTER 9 THE MOBILE GAMING MARKET 284

9.1 – Introduction 284

9.2 – The Major Players 288

9.2.1 – Mobile Developers And Publishers 288

9.2.2 – Mobile Distribution Platforms 289

Apple – The App Store And Apple Arcade 290

Google – Google Play Store And Google Play Pass 291

9 Mastering The Game

New Players 292

9.3 – Dealing With Mobile Distributors And Publishers 293

9.3.1 – What You Need To Know 293

9.3.2 – End-User Monetization Models 294

9.3.3 – The Publisher-Developer Relationship 297

Example Of The Mobile Development Process 299

9.4 – Entering Into An Agreement With The Distributor 301

9.5 – Major Terms Of The Distribution Agreement 304

9.5.1 – Rights Granted 304

9.5.2 – Delivery Of Materials And Acceptance 304

9.5.3 – Continuing Obligations 305

9.5.4 – Term And Termination 305

9.5.5 – Marketing 306

9.5.6 – Revenue Share And Pricing 306

9.5.7 – Legal Commitments 307

9.5.8 – Indemnification And Limitation Of Liability 308

9.6 – Regulatory Considerations 308

9.7 – Intellectual Property 313

CHAPTER 10 REGULATION OF THE GAME INDUSTRY 315

10.1 – Introduction 315

10.2 – Data Privacy 315

10.3 – Consumer Protection 320

10.4 – Advertising And Marketing 323

10.4.1 – What Forms Of Advertising Are Regulated? 326

10.4.2 – Common Issues 327

10.4.3 – Recognition Of Marketing Communications 327

10.4.4 – Influencers 328

10.4.5 – Misleading Advertising 330

10.4.6 – Microtransaction Disclosure 332

10.4.7 – Email Advertising 332

Mastering The Game

10

10.4.8 – Sweepstakes And Contests 333

10.4.9 – Social Responsibility 334

10.4.10 – Children 334

10.4.11 – Third-Party IP Rights 336

10.4.12 – Where To Find Additional Resources 336

10.5 – Monetization And Loot Boxes 337

10.6 – Other Regulations 339

10.7 – Ratings 340

10.7.1 – Age Ratings And Content Descriptors 340

10.7.2 – Factors In Rating A Game 347

10.7.3 – Submissions And Review 348

Ratings For Physical Games 348

Ratings For Online Games 350

Ratings For Mobile Games 350

CHAPTER 11 CONFIDENTIALITY AGREEMENTS AND DEAL

MEMOS 353

11.1 – The Purpose Of Confidentiality Agreements 353

11.2 – The Major Issues In A Confidentiality Agreement 355

11.3 – The Major Terms In The Confidentiality Agreement 356

11.3.1 – Preamble 356

11.3.2 – Confidential Content, Exclusions And Permitted Uses Of

Confidential Information 356

11.3.3 – Level of Care And Length Of Term 358

11.3.4 – Breach And Injunctive Relief 359

11.3.5 – No Commitment To A License Agreement 359

11.3.6 – Additional Terms 360

11.4 – Deal Memos: Purpose, Benefits, And Potential Problems 360

11 Mastering The Game

CHAPTER 12 COMMON CLAUSES IN AGREEMENTS 363

12.1 – Jurisdictional Issues 363

12.2 – Waiver, No Joint Ventures And Severability 365

12.3 – Assignment 365

12.4 – Survival 366

12.5 – Notices 366

12.6 – Entire Agreement And Revisions 367

12.7 – Reserved Rights 367

12.8 – Force Majeure 367

FURTHER READING 370

Law And Business 370

About The Industry 370

Web Sites 372

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 373

Mastering The Game

12

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

The videogame industry has grown dramatically in the last decade. It continues to

evolve with new technologies, trends, business models, greater accessibility to game

devices and distribution, and consequentially new legal and regulatory challenges.

These significant changes are reflected in the scope and volume of this second edition.

This publication is primarily a guide for developers, legal professionals, students, and

anyone interested in the video game industry to help them understand the many

business and legal issues developers may encounter in the development and eventual

distribution of a video game across numerous platforms. The topics range from

intellectual property (“IP”) and regulatory matters associated with game development to

forming relationships with publishers, platform manufacturers, distributors, and content

owners. In each of these relationships, the developer will need to be familiar with the

specific business and legal issues and contractual terms so that they can negotiate

effectively and identify risks in order to avoid potentially costly mistakes.

While the publication is for educational purposes and cannot replace the expertise of

lawyers and other key personnel in the video game industry in negotiating deals, it

hopefully can offer some guidance and explanations as to the major issues in

developing and distributing a game, why various parties make certain decisions during

negotiations, and the language that may be included in an agreement. Not all topics

and jurisdictions are covered; much of the legal commentary primarily reflects practice

in the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom, although many of

the business and legal principles discussed are applicable in other parts of the world. In

addition, these are large markets for video games, and with the ease in distributing a

game worldwide it is important for developers to have a basic understanding of some of

the issues they may come across when dealing with various publishers, distributors,

platform manufacturers, licensors and regulations in these territories. Finally, when

reading the publication, it is important to realize that laws change and every situation is

different and negotiations will vary depending on the unique circumstances between the

parties as well as bargaining power and perhaps past dealings. Some commentary is

reflected a few times in different chapters to underscore the importance of certain

business and legal terms.

The introductory chapter provides an overview of the video game industry, focusing first

on the industry’s size and comparing various numbers such as revenue and audience

to those of other sectors in the entertainment industry, providing a perspective of its

current dominant position. Next, a look at the demographics of game players and the

growing importance of new markets led by China followed by a brief discussion on the

major players, including the platform manufacturers, distributors, and publishers, And

lastly, a snapshot look at the recent economic and gaming trends driven by new

business models, esports, community involvement, influencers and immersive

technologies, and legal trends involving privacy, antitrust, labor and intellectual property

issues.

13 Mastering The Game

Chapter 2 discusses the basic IP issues and strategies associated with game

development. With advances in technology, IP issues have taken on a greater

significance in both the tools used to develop games and the content included in a

game. Without a basic understanding of intellectual property, a developer could find

themselves with a game that cannot be distributed because proper rights were not

obtained correctly.

This chapter examines the historical protection and current coverage for copyrights,

patents, trademarks, trade secret, and the right of publicity. Some significant cases in

the United States, the European Union, and the United Kingdom are discussed in detail

with some references to other jurisdictions and cutting edge legal topics are explored.

The authors also discuss balancing a game company's legal needs to protect IP with

the promotion of innovation and community development.

Chapter 3 examines the increasingly important role of independent developers and the

evolving relationship between developers and publishers, with a primary focus on the

business and contractual issues between the parties, whether the publisher is financing,

marketing, and distributing a game or is just serving as a distributor. The importance of

certain terms and why parties may negotiate them are analyzed, including rights,

ownership, development and delivery issues, payment considerations, and legal

responsibilities and obligations. Included in the chapter are a set of questions the

developer should consider when evaluating whether to enter into an agreement with a

publisher as well as what business issues a publisher may consider when looking at a

developer.

Chapter 4 deals with the major business and legal issues in licensing agreements

whereby the developer obtains rights to incorporate IP into their game ranging from

sports and iconic trademarks to music. In some situations, a game may be based on a

property such as a film, while in other situations, content may be incorporated into the

game to add realism. In both situations, certain rights are required, and this chapter

examines what steps the developer should take and factors to consider before licensing

a property, followed by a discussion on the terms in a typical licensing agreement. In

addition, as video games continue to grow in popularity, more and more IP originating

from video games is crossing-over into other forms of entertainment such as films,

publishing, music, and sports. This chapter discusses some of the contractual and

business issues a developer/publisher needs to consider when licensing out their IP to

other parties, including whether to hire an agent specializing in this field. The chapter

also includes an introductory discussion on music and what options exist for

incorporating music in a game, from the hiring of a composer to licensing or using public

domain music, and what are the main contractual issues when dealing with some music

agreements.

Chapter 5 deals with actor-talent agreements and the key terms typically negotiated

between the parties when hiring talent to appear in a game and marketing materials,

whether using their voice, likeness, or motion capturing them or a combination of any of

the above. The chapter also discusses the growing role of the actor’s union in the United

States and some of the procedures for hiring talent, and the minimum contractual

obligations required when hiring union talent.

Chapter 6 deals with the major terms in a vendor-independent contract agreement, and

some of the legal issues in hiring vendors which has taken on greater prominence as

Mastering The Game

14

developers/publishers hire more independent contractors, and changing labor laws in

parts of the United States.

Chapter 7 addresses important business and legal issues dealing with the major

console manufacturers and what steps are needed to develop and publish retail

packaged goods and digital goods on the various platforms.

Chapter 8 focuses on the growing importance of PC distribution as a way for developers

to reach consumers, as well as the challenges of distinguishing one game from another

in what is becoming a very crowded field. The chapter also examines some of the most

significant contractual terms between a developer and distributor, including rights

granted, revenue share, obligations, marketing issues, and termination rights.

Chapter 9 talks about the incredible growth of the mobile gaming industry, perhaps the

most accessible platform for developers to distribute their games on. Against this

backdrop, this chapter takes a brief look at the major platforms, and discusses the most

important legal and business issues that developers will need to be aware of, including

those in various agreements that a developer may enter into whether acting

independently with a distributor (i.e., app store) or through a publisher acting on its

behalf. While most distributors’ agreements are typically non-negotiable, it is still

important to understand the obligations and potential risks of these deals, which this

chapter will discuss.

Chapter 10 briefly examines some of the key areas of regulation that developers and

publishers need to be aware of when making a game, such as data privacy, consumer

protection, gambling, advertising, and marketing, including particular concerns dealing

with children and influencers. In addition, the chapter provides a brief overview of game

ratings and the importance of understanding how games are rated in some of the major

territories, and the impact of ratings on development.

Chapter 11 covers confidentiality agreements and deal memos, two significant

agreements that often serve as the foundation for any business relationship. The

confidentiality agreement will usually be the first agreement reviewed by a developer

when forming a relationship with another party, whether it is with a publisher interested

in financing a game or working with a platform manufacturer. This chapter will examine

the essential terms found in a confidentiality agreement. In addition, the chapter also

discusses the significance, necessity, and problems of a deal memo, as well as points

typically raised in the document.

Chapter 12 discusses the meaning behind common clauses that appear in almost all

agreements involving any aspect of the video game industry, ranging from publishing

agreements to licensing agreements.

15 Mastering The Game

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

David Greenspan has been involved in the video game business for over 25 years

working, independently and in Business and Legal Affairs for some of the most

significant video game publishers at the time in the industry. He has worked for 989

Studios/Sony, THQ, Bandai Namco Entertainment America, and Midway Games.

He has worked on more than 100 video games and has been involved in all aspects of

video game development, publishing, licensing, distribution, marketing, and has

negotiated hundreds of agreements covering these areas. Many of these deals have

involved major game developers, publishers, distributors, motion picture studios,

professional sports leagues, television networks, and advertisers. Although he is

terrible at playing games, he negotiated a favorable royalty rate one time by defeating

a licensor’s lawyer in a sports video game.

David was the lead author of the 1st edition of Mastering The Game: Business and

Legal Issues for Video Game Developers. Mr. Greenspan has taught classes for more

than 20 years covering video games, entertainment law, and licensing with a primary

focus on transactional issues. He has taught at several law schools, including Santa

Clara University School of Law, where he is currently teaching his 14th year, and also

recently at the University of Miami Law School. He was one of the first to teach legal

and business issues covering the video game industry at the university level when he

taught classes in this area at UCLA Extension from 1996-2000.

He has lectured at many conferences and universities about the video game industry

throughout the world, including many countries in Europe, Asia, and Central and South

America.

Dr. Gaetano Dimita is a Senior Lecturer in International Intellectual Property Law at

Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London where he

teaches ‘Interactive Entertainment Law’, ‘Interactive Entertainment Transactions’,

‘Esports Law’, and ‘Art & Intellectual Property Law’.

He is the editor-in-chief of the Interactive Entertainment Law Review (IELR –

https://www.elgaronline.com/view/journals/ielr/ielr-overview.xml), which he helped

launch as the first academic peer-reviewed journal in the field. The Journal, published

twice a year by Edward Elgar, features articles focusing on the legal changes,

challenges and controversies in the gaming space.

Gaetano created and organizes the ‘More Than Just a Game’ conference series (MTJG

- https://www.mtjg.co.uk/). a unique series of academic-led conferences on games and

interactive entertainment law attracting an international network of researchers and

legal professionals. MTJG now counts events in London (the flagship two-day

conference), Paris, Madrid, Frankfurt, Maastricht, Milan and Warsaw.

Mastering The Game

16

Gaetano serves as Executive Committee member of the British Literary and Artistic

Copyright Association (BLACA), as Board Member of the National Video Game

Museum (NVM); and as member of the UK IPO Copyright Advisory Council. He is also

a member of Italian Bar Association (Rome), the Video Game Bar Association, the Fair

Play Alliance, and the Higher Education Video Game Association.

Gaetano is a qualified lawyer (Italian Bar Association) and Of Counsel of an Italian Law

firm specialized in video game law, Andrea Rizzi & Partners, advising on Intellectual

Property Law, Licensing and Regulation.

S. Gregory Boyd is a partner and co-Chair of the Interactive Entertainment Group at

Frankfurt Kurnit. He is recognized in the 2022 edition of Best Lawyers in America for

advertising law and The Legal 500 has praised him for his work with media and

technology companies.

Mr. Boyd focuses on high technology companies in the video game industry,

advertising, and public relations. He has extensive experience negotiating and drafting

all of the operational agreements for these businesses, including software (SaaS),

licensing, employment, and development agreements — for video games and other

digital media across all platforms.

Mr. Boyd is co-author of Video Game Law: Everything You Need to Know About Legal

and Business Issues in the Game Industry (Taylor & Francis/CRC Press, Fall 2018). He

is also the co-author of the textbook Business and Legal Primer for Game Development

(Charles River Media), and wrote the chapter, "Intellectual Property in the Video Game

Industry" in the first edition of Mastering the Game.

He is a founding member and past Board member of the Video Game Bar Association

and a member of the Advisory Board for the NYU Game Center Incubator. He is a

frequent speaker at international media conferences and educational institutions, and

he has been featured in a number of publications, including Fortune, Forbes and

Gamasutra. Greg also taught a seminar on advanced topics in intellectual property for

six years at New York Law School. He is admitted to practice law in New York and is a

registered patent attorney with the USPTO

Andrea Rizzi is a dual qualified (Italy-UK) International commercial IP IT/media lawyer

with 20 years of experience gained in Italy and the UK, both as a private practice lawyer

as well as in house video game/interactive entertainment lawyer Andrea’s practice

focuses on the digital entertainment and technology industries. Throughout his career

Andrea has dealt with the most diverse legal issues related to the development,

acquisition, and commercialization of some of the most successful videogames of all

time, and has been involved with the setting up, acquisition, and sale of leading

development studios. Andrea counsels some key videogame industry players in all

major areas of business law and regulations.

17 Mastering The Game

CHAPTER 1

THE GLOBAL STRUCTURE OF THE VIDEO GAME

INDUSTRY

1.1 – The Current Video Game Industry Landscape: The

Numbers Behind The Industry

According to Newzoo, a leading video game research company, the video game

industry generated revenue of approximately $178 billion worldwide in 2020.

1

This

figure is greater than the current GDPs of 156 countries, according to 2020 United

Nations statistics.

2

This record-breaking year for the industry was accelerated by

COVID-19, with many people having spent their time playing video games at home

because of the pandemic lockdowns. Newzoo forecasts revenue numbers to slightly

increase to a little more than $180 billion in 2021 and increasing to $200 billion in 2023.

3

According to analysts, there are several reasons why it is expected that both revenue

and the number of players will continue to grow in the coming years:

• Digital accessibility will become more widespread in both emerging and established

markets.

• Greater market penetration of the next-generation console platforms, combined with

the continuing success of Nintendo’s Switch.

• More powerful mobile devices will be launched, which can run more content-

intensive games.

4

1

These numbers are projected to increase despite some AAA titles pushed back to 2022 releases, and fewer

consoles being manufactured because of a scarcity of some components. Newzoo’s 2021 estimated numbers

include consumer spending on physical and digital full-game copies, in-game spending, and subscription

services (i.e., Xbox Game Pass), but excludes secondhand trade or secondary markets, advertising revenues

earned in and around games, console and peripheral hardware, B2B services and online gambling and

betting. Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com. While

there’s no doubt that recent global revenue figures for the gaming industry are incredibly impressive,

determining an accurate figure is a challenge. Estimates of 2020 revenue in fact vary between $139.9 billion

and $208 billion according to the source. This is due to the different methods of calculation and to reporting

sources not necessarily having the same level of reliability. Additionally, many private companies do not

provide financial figures. Estimates are also complicated and vary widely because the platforms in the

industry, including in the different sectors such as mobile and digital, are not necessarily clearly defined.

2

“List of countries by GDP (nominal)”, wikipedia.org. Figures for 213 countries, compiled by the United Nations

Statistics Division and based on 2020 estimates.

3

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com.

4

Some games, including AAA titles, were not playable on previous devices because of the amount of memory

required. Currently, more major publishers are beginning to develop specifically for mobile platforms as well

as continuing to port AAA titles to mobile. This should expand their revenue streams, exposing more gamers

to these types of games.

Mastering The Game

18

• Esports,

5

cross-platform play and cloud gaming will further expand.

• Live services and video-game streaming services will grow.

• More innovative gameplay will be possible, incorporating new technology and

easier adaptability.

• Games will become more engaging, with more detailed stories and graphics, and

yet at the same time there will be games that are quite simple so anyone can play

them.

• Consumer interest will further increase due to the tremendous growth of streaming

of game content and user-generated video game related videos.

• Virtual reality (VR) will attract a more mainstream audience.

• More games will be localized making them accessible to a greater number of

players.

• Greater worldwide distribution and exposure of games from non-traditional markets.

• The Metaverse.

The current market revenue represents an increase of over 400% since 2007, when the

iPhone was introduced and revenues totaled $35 billion.

6

Compared to 1995, when the

PlayStation was introduced in the United States and the worldwide market was about

$4.3 billion, revenue has increased more than 4,000%.

7

Extraordinary growth has thus been achieved in a relatively short period, for an industry

that was on the verge of collapse in the 1980s.

8

Video games have become the primary

form of entertainment for many people (this is especially true for a younger generation

of players where games have become the center of youth culture). The social and

artistic relevance of video games has become just as influential as other forms of

entertainment – if not more. Video game revenue exceeds that earned in the film,

9

book

5

Professional or semi-professional competitions using video games. See Section 1.7.4.

6

Newzoo, “2018 Newzoo Global Game Market Report”.

7

Shapiro, Eben, “Sony, Nintendo’s Partner, Will Be A Rival, Too”, The New York Times, June 1, 1996.

8

It was close to collapse at that time for several reasons: (i) retailers sending back massive stock to companies

(infamously due to the massive failure of the E.T. game for the Atari 2600), (ii) a market saturated with too

many console systems, (iii) a high number of poorly made games, and (iv) unsold games sitting in stores and

warehouses. The Strong Museum, A History of Video Games in 64 Objects, Dey St., 2018, p. 158. See also

“Video Game History”, history.com, June 10, 2019.

9

Film industry figures can vary according to the definition of what is included as revenue. The most reliable

numbers are probably those of the Motion Picture Association (“MPA”), based in the United States, which

serves as an industry trade group. In 2020, the MPA formerly known as the Motion Picture Association of

America ("MPAA") reported that the combined global theatrical and home/mobile market was $80.8 billion

(excluding the pay television subscription market). This represents an 18% decrease from the record-breaking

year of 2019, when worldwide revenue reached $101 billion, in turn an 8% increase over 2018 and the first

time figures surpassed $100 billion. Not unexpectedly, global box office revenue dropped substantially (about

72%) as theaters were closed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2020, global box office revenue accounted

for $12 billion in comparison to $42.2 billion in 2019. In contrast, digital revenue increased to $69.8 billion in

2020 from $48.7 in 2019. The MPA figures on revenue included that of movie theaters; content viewed digitally

or on a disc, both home-based and on mobile devices including electronic sell-through; video on demand and

subscription streaming; and estimates of subscriptions to television and online video services. Revenue from

film-related merchandise and pay-television subscription revenue was not included as part of the study.

Motion Picture Association, “2020 Theme Report”, motionpictures.org.; and Motion Picture Association, “2019

Theme Report”, motionpictures.org.

19 Mastering The Game

publishing,

10

and music industries. Moreover, video game revenue far surpasses

revenue generated by the major sports leagues from around the world. Video games

are also growing in importance for other entertainment sectors, as they provide a major

source of Intellectual Property (“IP”) for motion pictures, licensing and television

broadcasting (including esports). They even act as concert venues for musicians.

Not only have video games become the number one source of entertainment, but they

also continue to play a growing role in other aspects of society, including social

interaction, education, health, science and the military.

Revenue Earned In 2019 (Blue) And 2020 (Green) For The Video Game, Book

Publishing, Film And Music Industries

Comparing 2019 and 2020 revenue among the various forms of entertainment provides

perspective on the size of the video game industry and why many now consider it the

number one form of entertainment. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, revenues were

increasing across the entertainment and sports industries, primarily driven by

accessibility to content, higher ticket prices, streaming, expanded broadcasting rights

and merchandising. But 2020 saw an abrupt reversal of fortune for the traditional

entertainment and sports industries. The film, sports (professional and collegiate) and

music industries saw their revenue drop considerably due to cancellations of live

10

The Book Publishers Global Market Report 2021 noted that the global book publishers’ market was $87.92

billion in 2020, a decrease from the $92.8 revenue generated in 2019. The report indicated that the industry

is expected to reach $92.68 billion in 2021. “Global Book Publishers Market Report (2021 to 2030) – COVID-

19 Impact and Recovery-Research”, businesswire.com, April 13, 2021. See also “Book Publishers Industry

to Decline from $92.8 Billion in 2019 to $85.9 Billion in 2020 – Trends & Implications of COVID-19”,

prnewswire.com, May 27, 2020.

0

45

90

135

180

225

VIDEO GAMES BOOK PUBLISHING FILM MUSIC

Mastering The Game

20

events

11

and of film and television productions.

12

As a result, the revenue gap between

the video game industry on the one hand and the film, sports and music industries on

the other grew wider.

The film industry had its most successful year in 2019, reaching $101 billion in

worldwide revenue: in 2020 this figure dropped to $80.8 billion primarily caused by the

closure of theaters which saw a 72% decrease in revenue. The music industry

generated approximately US$57.5 billion in worldwide revenue in 2020 down by about

25% from the previous year.

13

Revenues of the National Football League, the most

successful sports league in the United States, reached $16 billion in 2019 and dropped

to a little more than $12 billion in 2020.

14

The English Premier League, the most

11

How important are live sports events for the overall revenue stream for the leagues? For the major sports

leagues based in the US, stadium revenue according to Forbes in 2020 accounted for close to 40% of the

league’s revenue with the numbers being substantially higher for the professional hockey league (the NHL

was at 70%). Birnbaum, Justin, “Major Sports Leagues Lost Jaw-Dropping Amount of Money in 2020”,

forbes.com, March 6, 2021. See also Kochkodin, Brandon, “U.S. Pro Sports Prove Big Enough to Handle $13

Billion Sales Hit”, bloomberg.com, November 5, 2020. Of course these numbers can fluctuate especially with

broadcasting fees increasing as traditional and online broadcasters compete for content.

12

The video game industry suffered less economic impact in comparison, primarily due to its remote

development; growth of digital distribution (which was also true for the other sectors); and the small financial

role played by live events, these latter being critical to the sports, music and film industries. But at the same

time, the industry was still impacted from component shortages for new consoles (manufacturers have

lowered their production numbers for their 2021 fiscal year) to graphic cards to delays with the release of

games (this will probably have a greater affect on 2021-22 revenues)This is especially true with AAA titles

because of problems including coordination of development and manufacturing, certification from the platform

holders and production and shipping issues for retail products. The effects of the pandemic on the film industry

appear to have been more severe: when filming did eventually move forward following production suspension,

production companies had to comply with several on-set restrictions that increased costs and filming time.

Video game development was affected to some degree, but its developers, artists, coders, and even

musicians and voice-over artists can work separately, whereas film production relies on people being

physically together on set to make the product. Because of pandemic restrictions, theaters closed or severely

limited the number of theatergoers, thereby reducing a significant stream of revenue. Consequently, the film

industry may need a bit of time before it catches up to its 2019 figures. There are also concerns that many

theaters could close permanently. See Aswad, Jem, “Music Revenue to Drop 25% in 2020, but Long-Term

Outlook is Good: Goldman-Sachs”, variety.com, May 20, 2020.

13

Wang, Amy X., “Goldman Sachs Expects Global Music Revenue to Drop 25% This Year”, rollingstone.com,

May 15, 2020. While music streaming led by Spotify and Apple Music has driven recorded revenues higher

(similar to video games whereby an abundance of content is easily accessible on a mobile device), the

industry suffered from a lack of live events which to date has made up a major source of overall revenue. The

2020 estimated numbers mentioned were provided by Goldman Sachs Music in Air Report 2021, and cover

revenue generated from recorded music, publishing, and live events. Goldman Sachs, “The Music in Air

Report 2021”, goldmansachs.com. See also Ingham, Tim, ”Goldman Sachs: Universal is Worth Over $50BN,

and Global Music Streaming Revenues will Rise $3BN this Year”, musicbusinessworldwide.com, April 29,

2021.

14

In many countries revenue from video games will exceed revenue earned by sports leagues. In the United

States fo example, according to NPD, an analytics company, video game software sales in the United States

reportedly grew to a record $49.9 billion (overall spending was $56.9 billion) in 2020 from $35 billion in 2019.

Entertainment Software Association, “U.S. Video Game Content Generated $35.4 Billion in Revenue for

2019”, theesa.com, January 23, 2020. In comparison, looking at the major sports leagues in the United States,

The NFL earned $16 billion in 2019 dropping to about $12 billion in 2020. NBC Sports, “NFL Revenue Drops

From $16 Billion in 2019 to $12 billion in 2020”, nbcsports.com, March 11, 2021. Major League Baseball

earned $10.7 billion in 2019 and about $4 billion in 2020. Young, Jabari, “Major League Baseball revenue for

2019 season hits a record $10.7 billion”, cnbc.com, December 22, 2019; and Ozanian, Mike, “MLB Teams

Lost $1 Billion In 2020 on $2.5 Billion Profit Swing”, forbes.com, December 22, 2020. The National Hockey

League consisting of teams throughout North America earned $5.09 billion based on the 2018-19 season and

sliding to about $4.4 billion in 2020. Gough, Christina, “National Hockey League – total league revenue from

2005/06 to 2019/20”, statista.com, February 2, 2021; and Birnbaum, Justin, “Major Sports Leagues Lost Jaw-

Dropping Amount of Money in 2020”, forbes.com, March 6, 2021. “The NBA earned -$8.76 billion based on

the 2018-2019 season but dipped to around $8.3 billion for the 2019-2020 season”, statista.com; and

Wojnarowski, Adrian & Lowe, Zach, “NBA revenue for 2019-20 season dropped 10% to $8.3 billion, sources

say”, espn.com, October 28, 2020. Although revenue will vary by source, for a list of sports leagues revenue

as compiled by Wikipedia, see “List of professional sports leagues by revenue” available at

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_professional_sports_leagues_by_revenue.

21 Mastering The Game

significant football (soccer) league in England, generated approximately $7.1 billion in

revenue in 2018-2019 and approximately $5.9 billion in 2019-2020.

15

Not only is revenue in the video game space exceeding that of sports leagues, but it

also drawing television audiences from esports events that are either exceeding those

of some of the major sports leagues or close behind. According to the technology

consulting firm Activate, more than 250 million people watch esports. Activate forecasts

that, with the exception of the NFL, more people will watch esports than those who

watch American professional baseball, basketball, hockey, and soccer.

16

Several major video game titles have budgets comparable to Hollywood movies. And

while the two industries have many similarities, the differences of the video game

industry have enabled it to grow – especially during the pandemic – in more ways than

the film industry and other entertainment media. One difference is that video games can

be continually updated for many years with new content, thereby avoiding the costly

and unpredictable outcome of sequels. A second is that video games can be relatively

easily distributed on certain platforms throughout the world, while films still rely on

theatrical releases as a major source for revenue and publicity. A third is that there are

fewer challenges in making video games compared to films. Indeed, although AAA

video game titles may take years to develop and involve issues similar to those

associated with film production, many games –especially lower-budget mobile games –

do not involve nearly as many obstacles, making them easier to produce and

distribute.

17

Finally, another difference that contributes to the success of video games

is the ongoing engagement of consumers, i.e., their active involvement in playing

against each other in games such as Fortnite or in watching and commenting on games

either as part of an esports tournament or on video game live-streaming platforms such

as Twitch and YouTube or even creating content. This engagement leads to

tremendous daily publicity and connection between developers, streamers and fans.

One similarity between the video game and film industry is their reliance on major

franchises. A relatively small number of top franchises make up a significant portion of

revenue in the various sectors (e.g., console and mobile). For many AAA publishers,

their major franchises account for a considerable portion of their income and a

disproportionate share of their profits.

18

15

Garner-Purkis, Zak, “Don’t Be Fooled by the Premier League’s $1 Billion Predicted Revenue Drop”,

forbes.com, June 11, 2020; and Lange, David, “Premier League Football Clubs Revenue in England (UK)

from 2014/15 to 2020/21 by Revenue Stream”, statista.com, September 28, 2020.

16

“Activate Technology & Media Outlook 2020”, slideshare.net, October 22, 2019. A major reason for

professional sports interest in esports is the hope to attract the relatively young demographic groups who

make up their fan base. Many potential young sports fans may now spend their time playing video games

instead of watching and playing sports which clearly concerns sports leagues trying to build their base. One

of the issues with esports attaining a mainstream television audience is that the viewer may not understand

how the game is played, especially with all the nuances that make games unique.

17

Most films involve very time-consuming procedures: acquiring a property or creating an original work,

financing, hiring talent, and dealing with multiple unions covering the various stages of production.

18

The top 10 gaming franchises in the US in 2020 were all established prior to 2020, illustrating how difficult

it can be to crack the top-ten market. See Activision Blizzard, ‘‘2020 Annual Report’, investor.activision.com.

Examples of the significance of major franchises owned by AAA publishers include the FIFA franchise, which

represented approximately 12% of Electronic Art’s net revenue in their fiscal year 2020. Electronic Arts, “2019

EA Annual Report”, ir.ea.com. Call of Duty, Candy Crush, and World of Warcraft collectively accounted for

76% of Activision Blizzard’s consolidated net revenues in 2020. Activision Blizzard, ‘‘2020 Annual Report’,

investor.activision.com. Similarly, for Take-Two, Grand Theft Auto products provided 29.26% of the

company’s net revenue for the fiscal year ending in March 2021. Take -Two Interactive, “Take-Two Interactive

2021 Annual Report”, ir.take2games.com.

Mastering The Game

22

1.2 – Demographics

In addition to the impressive economic numbers, the number of people playing video

games and the changing demographics over the years also illustrate the growing

popularity of games throughout the world, regardless of age and gender. According to

a 2021 Newzoo report, approximately 3 billion people throughout the world play video

games with the Asia-Pacific market making up 55% of the world’s players followed by

the Middle East and Africa (Newzoo lists this as one region), Europe, Latin America and

North America. Despite, North America representing 7% of the worldwide market, the

United States was second in revenue earned with Canada ranked eighth.

19

Not too long ago, the market was dominated by young males,

20

but today games are

played by both men and women of all ages. Women gamers are narrowing the gap with

men in numbers of players, as they now make up close to 46%,

21

although men still

spend more time playing games.

22

According to a game’s genre, platform and country,

it can happen that more women than men play certain games. In Japan, for example,

two out of three gamers are female.

23

Today, the average age of a gamer is approximately 34

24

but varies slightly by country.

The age group is very broad, as the range can include, for example, a 5-year-old playing

a simple game which one author cannot figure out on an i-Pad, a teenager playing with

friends, a 45-year-old who grew up playing games in the 1990s and 2000s and who

continues to play, and even a 70-year-old who plays a card game on a mobile device

for 10 minutes at a time. Still, the most important age category is 18-35. They spend the

most time playing and spend the most money on games; which can also include

spending above and beyond their own consumption and on behalf of their children or

family members under 18.

This change in demographics over the years, which led to gaming being played by all

ages, has been driven by the easy access to games (i.e., mobile devices and web portal

games such as Roblox). Another factor is the incredible variety of games at various

price points, from easy-to-play mobile hyper-casual games that are highly advertised,

to elaborate multi-million-dollar console games.

There are a wide variety of video game genres as well. Stories and settings can be just

as varied as movies: sci-fi, action, western, comedy, historical or romantic. Even within

a genre, there can be variety from one title to the next. Some examples are “first-person

shooters”, where shooting is done from a “point-of-view” perspective; “role-playing”,

known as “RPG”, in which the player takes on the role of a character; “casual” or “social,”

in which the objective of the game is to interact with friends; sports games, in which the

end-user controls the athletes and teams; and battle royale games, which are basically

19

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com; and Wijman,

Tom, “The World’s 2.7 Billion Gamers Will Spend $159.3 Billion on Games in 2020; The Market Will Surpass

$200 Billion by 2023”, newzoo.com, May 8,2020.

20

In 1995, there were reportedly 30 million gamers, and half were 18 or younger. Elrich, David J., “ROAD

TEST; 32-Bit Video Games: Newest Kid on the Block”, nytimes.com, September 14, 1995.

21

The number was based on 33 markets and was a representative sample of the online population aged 10-

65/10-50. Newzoo, “Consumer Insights-Games & Esports”, newzoo.com.

22

“Marketing To Gamers: What To Know About The Ever-Expanding Market”,

insights.digitalmediasolutions.com, June 22, 2020.

23

Ibid.

24

“2021 Gaming Industry Statistics, Trends, Data”, gamingscan.com, June 2021.

23 Mastering The Game

a last-man-standing multiplayer experience. The design of a game is as varied as the

ideas the developer can come up with.

Quite simply, a great percentage of the world’s population can play any type of game at

any time, anywhere in the world, and thanks to this the number of gamers continues to

grow. Furthermore, developers have recognized that games can focus on any age

category, gender and skill level and still be profitable.

1.3 – Geographic Breakdown

1.3.1 – The Major Revenue-Generating Countries

Historically, the gaming market has been dominated by the United States, Japan and

Europe, in terms of both consumer spending and game development. All the major

console devices have been developed either in Japan or the United States, and the

major publishers have also been from those countries, with a few based in Europe. But

that picture has changed dramatically within the last few years, with mobile devices and

digital distribution having now made video games easily accessible, especially in

countries where gaming had a smaller presence. According to Newzoo estimates,

92 million new gamers entered the market, mostly as mobile gamers, in 2020.

25

Nowhere have changes in the industry been more evident than in China. One of the

significant reasons for the incredible growth in the industry has been the emergence of

new markets led by that country. With its growing economy, billion-plus population, and

access to smartphones, China has become one of the biggest players in the industry,

not only from a consumer and revenue standpoint, but also for its growing role in

publishing, distribution, esports, software development and manufacturing of hardware

such as consoles and smartphones. China is now the largest market in the world with

gamers and generates the most revenue.

26

It is also home to some of the biggest

publishers in the world, such as Tencent and NetEase, which continue to expand their

presence on a global scale.

27

At the same time while the Chinese market offers the possibility of incredible economic

benefits for publishers and developers, China is a cautionary tale, as regulations

imposed by the government can be unpredictable and present challenging and

significant obstacles for publishers. Some of these obstacles include:

1. For a game to be distributed in China, it must be approved by the government and

receive a publishing license (ISBN).

28

25

Newzoo, “2020 Global Games Market Report”, newzoo.com.

26

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com.

27

In the last few years, Chinese companies have expanded their game distribution into new countries and,

led by Tencent, have also been investing in established companies. Tencent is the largest game company in

the world; they purchased Riot Games and have acquired varying interests in Supercell (Finland), Epic Games

(US), Glu Mobile (US), Funcom (Norway), Bohemia Interactive (Czech Republic), Bluehole (South Korea),

Marvelous (Japan), Grinding Gear (New Zealand), Activision Blizzard (US), Ubisoft (France), and Paradox

Interactive (Sweden). Frater, Patrick, “Tencent Accelerates Games Company Acquisitions”, variety.com, June

3, 2020.

28

Over the last few years, the Chinese government has approved fewer games and it is even harder to get

approval for international games which must be localized into Chinese. At the end of December 2020, Apple

Mastering The Game

24

2. In order to distribute a game in China, a publisher or a developer must work with

a Chinese based company.

3. At the time of writing, platforms such as Google Play and Twitch are prohibited.

4. New releases are at times prohibited.

29

5. Games from certain countries have been denied access to the Chinese market.

30

6. Severe limitations on the amount of time minors can play games known as “anti-

fatigue rules”.

31

7. Content regulations covering a number of areas that can be unpredictable.

32

removed 39,000 games from their app store for failing to comply with China’s licensing requirements. Li, Pei,

“Apple Removes 39,000 game apps from China store to meet deadline”, reuters.com, December 31, 2020.

Epic Games in November 2021 announced that after two years of beta testing Fortnite in China, they would

stop pursuing distributing the game in China after it failed to obtain regulatory approval. and were prohibited

from introducing microtransactions. Kain, Erik “Fortnite is Calling it Quits in China”, forbes.com, November 2,

2021. It appeared that the economics probably didn’t work with a prohibition on microtransactions and the

limitations imposed on minors that significantly reduced the amount of hours they could play games.

29

In 2018, the government suspended license approval for new games for both Chinese and foreign games

for nine months. This decision reportedly cost the industry billions of dollars, including losses of $1.5 billion

by Tencent. Liao, Shannon, “Apple blames revenue loss on China censoring video games”, theverge.com,

January 29, 2019.

30

Although no official notice was released, China effectively imposed a blanket ban on new games from South

Korea from March 2017 to February 2020, but since then seven games have received ISBN numbers as of

July 2021. Jung-a, Song, “China Approves First Sale of Korean Video Game in Four Years”, ft.com,

December 3, 2020; and Takahashi, Dean, “China is approving more foreign games, but not so many American

ones”, venturebeat.com, February 18, 2020.

31

The Chinese government has introduced a series of regulations over the years restricting the amount of

time children under the age of 18 can play video games. The government has enacted these measures

claiming to protect the physical and mental health of minors by preventing game addition and myopia. Ni,

Vincent, “China Cuts Amount of Time Minors Can Spend Playing Online Video Games”, theguardian.com,

August 30, 2021. For some of the previous restrictions involving minors and gameplay see the following

source for a list of the current National Press and Publication Administration anti-fatigue rules in China:

Pilarowski, Greg et al., “Legal Primer: Regulation of China’s Digital Game Industry”, pillarlegalpc.com,

January 6, 2021. In August 2021, China’s National Press and Public Administration (NPPA) issued what at

the time of writing is its most restrictive measure, which includes lowering the number of hours a minor can

play online games from 13.5 to 3 hours per week, and only from 8 to 9 p.m. on Fridays, Saturdays, Sundays

and other legal holidays. Pilarowski, Greg, Yu, Charles, and Ziwei, Zhu, “China Limits Minor Online Game

Time to Three Hours Per Week”, pillarlegalpc.com, September 14, 2021. Shortly thereafter, the government

announced that live streaming services including those involving games would be prohibited from allowing

anyone under 16 from registering to stream online. Sinclair, Brendan, "China Bans Livestreaming by Children

Under 16”, gameindustrybiz.com, September 27, 2021. South Korea also imposed laws limiting players under

16 from playing games from midnight to 6:00 a.m. According to the government, the law known as the

Shutdown Law, and enacted in 2011, was aimed at preventing game addiction. At the time of writing, the law

was in the process of being revoked. Im Eun-byel, "Korea to ax games curfew”, koreaherald.com, August 25,

2021; and Bahk Eu-ji, “Korea to Lift Game Curfew for Chlldren”, koreatimes.co.kr., August 25, 2021.

Both Tencent and NetEase introduced various limitation practices, including time limits on certain games,

gamer ID checks and facial recognition to confirm a player’s age to deal with myopia and game addiction.

Handrahan, Matthew, “NetEase to impose restrictions on young gamers in China”, gamesIndustry.biz,

January 25, 2019; and Valentine, Rebekah, “Tencent adds ‘digital lock’ to certain games in China”,

gamesindustry.biz, March 1, 2019. Also, in 2021, more Chinese companies agreed to consider using facial

recognition to help enforce governmental time limitations on minors. Batchelor, James, "Over 200 Chinese

Games Firms Reportedly Vow to Self-regulate in Face of New Restrictions”, gameindustry.biz., September

24, 2021. Computer cafes, which are used by a significant portion of the gaming community in China, now

require IDs to verify that customers are age 18 or older.

32

While most countries have some form of restrictions or warnings on content (imposed by the government

or by industry self-regulatory bodies), China imposes some of the most restrictive limitations involving

violence, political content, distortion of history and sexual relationships. Some of the regulations are vague,

difficult to predict what may be allowed, and are constantly changing. In addition China appears to be heading

towards additional content restrictions involving history, religion, and character gender, to name a few.

Rousseau, Jeffrey, “Chinese Government Tightens Video Game Restrictions”, gameindustry.biz, September

30, 2021. For a list of content regulations in China see Pilarowski, Greg et al., “Legal Primer: Regulation of

25 Mastering The Game

8. Prohibitions on game consoles have previously existed.

33

9. Enforcing intellectual property rights can be challenging.

10. Some of the broadest rules involving data privacy.

34

The United States, as the home to some of the biggest publishers, has always been the

biggest market and has consistently generated the highest revenues over the years until

smartphone presence became widespread in China.

Behind the United States and China is Japan, which is home to Sony, Nintendo and

several major publishers such as Bandai Namco, Sega, Square Enix, Capcom and

Konami. The remaining top revenue-generating countries are South Korea, which has

been a leader in esports and technology as well as home to major publishers such as

NCSoft and Netmarble, followed by the United Kingdom, Germany and France.

35

1.3.2 – Regional Markets

The Asia-Pacific market, led by China, Japan and South Korea, is the largest regional

market in terms of revenue. According to Newzoo, this market is projected to generate

$88.2 billion in 2021, accounting for slightly over 50 % of the global market.

36

This

market also includes India with its population of over 1.3 billion and the world’s second-

largest smartphone market.

37

even though only about 32% of the population in 2021

owns a smartphone which is by far the lowest of the top 20 countries by users.

38

However, according to the mobile research company data.ai formerly known as App

Annie, India is the world’s biggest mobile game market by downloads,

39

making it

potentially the next big market. North America is the second-biggest market, followed

by Europe.

40

Latin America is a distant fourth but continues to grow as its bandwidth

China’s Digital Game Industry”, pillarlegalpc.com, January 6, 2021. See also Pilarowski, Greg et al., “China’s

New Game Approval Requirements”, pillarlegalpc.com, May 17, 2019. Some commentators have noted that

a country may prohibit a game in their territory if the government considers the game to include unfavorable

content, no matter where the game is distributed. Therefore, a game can meet a country’s regulations and

still be prohibited because of violent or political, etc., content in the versions of the game distributed outside

that country. See Fahey, Rob, “Gaming will be a frontline in China’s censorship drive | Opinion”,

gamesindustry.biz, October 9, 2020.

33

China legally permitted distribution of PlayStation and Xbox in the country only in 2015. D’Orazio, Dante,

“China officially ends ban on video game consoles”, theverge.com, July 25, 2015. It was the ban on consoles

and software piracy issues that led to the growth of online gaming in China.

34

China implemented in November, 2021, a new privacy law known as the Personal Information Protection

Law (PIPL) to some degree modeled after Europe’s GDPR but more challenging for gaming companies

because many of the restrictions are very vague and difficult to determine at this time what might fall within

the law. The law limits both Chinese and foreign companies from collecting consumer information without

their consent; from storing more personal data than necessary; and restricts Chinese nationals’ personal data

out of the country. Dou, Eva, “In China, escalating cost of business sends some companies to the exits”,

washingtonpost.com. November 25, 2021. See also Creemers, Rogier and Webster, Graham, “Translation:

Personal Information Protection Law of the People's Republic of China-Effective November 1, 2021",

digichina.stanford.edu, August 20, 2021, revised September 7, 2021.

35

Ranking of top ten countries by estimated video game revenue for 2020. “Top 10 Countries/Markets by

Game Revenue”, newzoo.com. See also: “Top 100 Countries by Game Revenues”, knoema.com, August 13,

2019.

36

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com.

37

Singh, Bhupinder, “Top 20 Countries with Most Smartphone Users in the World”, indiatimes.com, July 20,

2021. Historically, India has not been a major market, possibly due to a hesitant role out of consoles and the

cost of hardware which may have been out of reach for most of the population.

38

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com.

39

App Annie “2021 Mobile Gaming Tear Down”, appannie.com.

40

See 2019 European Video Games Industry Insight Report written by the European Games Developer

Federation (EGDF) and the Interactive Software Federation of Europe (ISFE) available at

Mastering The Game

26

capacity improves and gaming population increases. Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Chile

and Colombia are the leaders in revenue there and are home to growing development

communities. Africa and the Middle East are the smallest market but also shows

potential for growth.

41

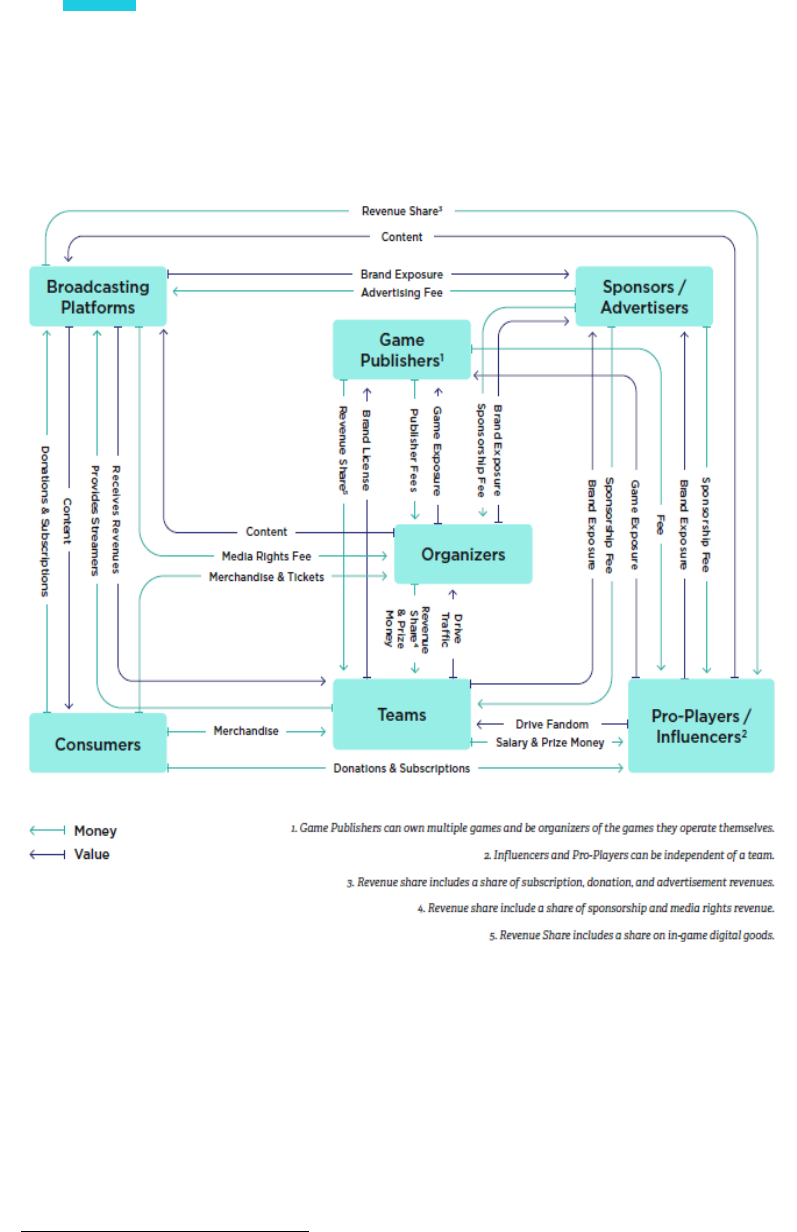

Regional Revenue Distribution

42

© Newzoo

1.4 – Current State Of The Video Game Industry: The

Players

The continuing growth of the video game industry has been fueled by new forms of

distribution, business models, technology and easy access to devices that can play

games and can connect people across the globe, thereby creating a unique social

platform. This growth includes an assortment of different players such as consumers,

independent developers, publishers, regulators, streamers and ancillary industries. As

a result, the industry is constantly evolving and is quite complicated: it requires some

http://www.egdf.eu/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/EGDF_report2021.pdf. For additional information on the

state of the industry in individual European countries see http://www.egdf.eu/category/data-studies/egdf-

members/. Many of the reports discuss either a specific issue within a country (e.g., esports, VR), or provide

an overall picture of the industry within the country, and may cover such issues as the state of the development

community, games originating from that country, legislation, and investment and educational opportunities.

The reports are either in the native language or English and most are updated annually.

41

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com. See also

“Newzoo Global Games Market Report 2019” on the same website for a more detailed analysis of regional

revenue from 2019.

42

Chart based on 2021 projections. Ibid.

27 Mastering The Game

explanation to be fully understood. This section will provide a general overview of the

industry by outlining the current platforms, distribution channels, major companies,

areas of growth and some of the major new challenges.

1.4.1 – Game Distribution: The Platforms

Not too long ago, the video game market was dominated by the major console

manufacturers. Sony, Nintendo and Microsoft were the gatekeepers of the industry at a

time when personal computer (PC) gaming had lost much of its significance and mobile

and digital platforms had yet to make their mark.

2021 Estimates by Newzoo

© Newzoo

Fast forward, and the industry is now dominated by mobile devices such as

smartphones and tablets (with an 80-20% split). These make up over 50% of the global

market and are projected to reach approximately 52% in 2021.

43

Mobile has become the number one platform thanks to easy access to devices and

games, various price points including free-to-play and improved quality. Furthermore,

increasingly powerful mobile devices are covering all types of genres. The console

platform still plays a significant role in some countries, but not as much in markets

dominated by mobile. Nevertheless, consoles sales and distribution of games

associated with that platform, whether retail or digital, generated the second-highest

43

Ibid.

Mastering The Game

28

revenue. In fact, revenue from console sales is expected to grow as a result of the

relatively recent releases of new consoles by Sony and Microsoft, and the continuing

strong sales of Switch. Despite chip shortages and delays in the distribution chain due

to the COVID-19 pandemic, sales numbers, although less than what had been

forecasted, have been relatively strong for the consoles.

44

At the same time, the PC platform has bounced back in recent years to likewise play a

prominent role, thanks to digital distributors such as Steam, publisher-developer digital

platforms and the emergence of Epic’s Game Store. For many people, PC has also

become the preferred platform to stream, participate in stream sessions, make and post

video content about games, and play dedicated in-browser games.

Video games can be divided into three distinct platforms: console, PC and mobile.

Console games run on dedicated hardware that connect to a television (e.g., Microsoft

Xbox One Series). PC games run on general-purpose personal computers (with

Windows being the most common operating system), and mobile games run on various

types of mobile devices including smartphones and tablets.

45

THREE PLATFORMS OF VIDEOGAMES

CONSOLE

PC (PERSONAL

COMPUTER)

MOBILE/CASUAL

• Run on dedicated

hardware

• Expensive to develop

• Wide variety of genres

• System controlled

by IP owners

• Box product and

digital

• Run on Windows,

Mac or Linux

• Wide variety in

price and genre

• No single

gatekeeper for

platform

• Most sales

through digital

• Run on tablets and

phones

• Least expensive to

develop, but

development costs

increasing and difficult

to retain players

• All genres, but social

and casual games play

a big role

• Largest number of

gamers

1.4.2 – Console Manufacturers And Various Platforms

The so-called traditional video game market made up of consoles and PC gaming still

plays a crucial role in the industry but, as a result of mobile’s increasing popularity, no

longer plays the dominant role it once did. Console-related revenue, which includes

retail and digital sales, is projected to generate a bit more than $50 billion in 2021, a

decrease of about 9% from 2020.

46

44

As of October 2021, Sony had sold over 13.4 million PlayStation 5 units. Purslow, Matt, “Sony Has Now

Sold 13.4 Million PlayStation 5 Consoles” gamesindustry.biz, October 28, 2021.

45

For Cloud Gaming see Section 1.5.3.

46

Newzoo, “2021 Global Games Market Report: The VR & Metaverse Edition”, newzoo.com.

29 Mastering The Game

Console hardware entered its ninth generation with the release of PlayStation 5 and

Xbox Series X and Series S in November 2020. While both are reported to have broken

records for units sold at their initial launches,

47

previous consoles (e.g., PlayStation 4)

will still play an important role for the next few years as developers continue to produce

games for those platforms, taking advantage of their huge installed base and the

shortage of available new consoles because of manufacturing problems (i.e., chip

shortages) brought about by the COVID-19 pandemic.

PlayStation 4 was released in the United States in November 2013. It had sold over

116 million units worldwide as of July 2021 and became the second-best-selling

PlayStation behind PlayStation 2 while selling the most games for any console.

48

Nintendo Switch, which can be used as either a console or portable device, released in

March 2017, has sold a bit more than 89 million units as of June 2021

49

and enjoyed the

highest number of first-year sales of all other consoles.

50

Microsoft comes in a distant

third with Xbox One, released in November of 2013 in the United States. It had sold

about 50 million units as of January 2021.

51

In addition, each platform provides various

subscription services at different price points for purchasing downloadable games,

additional content, game demos, multiplayer gaming and cloud storage.

The popularity of each console varies greatly by geographic market, although the United

States is the leader in sales of each console, as well as in sales for software. This can

be clearly seen by the fact that almost 70% of Xbox One sales occur in the United

States, while at the same time its sales are almost non-existent in Japan, which is the

number two country in sales for PlayStation 4 and Nintendo Switch.

52

The dominance of premium console game sales in North America and Europe is further