AIR TRANSPORT CASE STUDY

ICAO/IDB

THE IMPACT OF AVIATION REFORMS IN THE DOMINICAN

REPUBLIC: A MODEL OF SOCIOECONOMIC GROWTH AND

DEVELOPMENT

The Inter-American Development Bank

Eduardo Café

Victor Gomes

Reinaldo Fioravanti

Reviewed by Manuel Rodriguez Porcel

2

1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 4

2. Executive Summary ........................................................................................................ 6

3. State Profile .................................................................................................................. 11

4. State of Air Transport and Connectivity ......................................................................... 12

4.1. State of Air Transportation: general statistics, main destinations and airlines ........ 12

4.2. Dominican Republic Airlines .................................................................................. 20

4.3. Cargo Statistics ..................................................................................................... 21

4.4. Air Connectivity: Direct Routes, Destinations and Airlines...................................... 27

4.5. The Caribbean: Regional Benchmarking ............................................................... 31

5. Policy and Regulation ................................................................................................... 35

5.1. National Framework for the Air Transport Sector ................................................... 35

5.2. Air Services Agreement (ASAs) and Share Code Agreements .............................. 39

5.3. Aviation and Environment ...................................................................................... 41

5.4. Other Policies that have benefited the Aviation Sector ........................................... 44

6. Civil Aviation Safety and Security Oversight: Regulatory Framework, Operations and

Capacity Building ................................................................................................................. 46

6.1. Regulatory Framework and Operations ................................................................. 46

6.1.1. Aviation Security ................................................................................................ 46

6.1.2. Safety Matters .................................................................................................... 47

6.2. Certification of Airplane Ground Handling Services Companies ............................. 48

6.3. Capacity-Building ................................................................................................... 48

6.3.1. Superior Academy of Aeronautic Sciences ......................................................... 49

6.3.2. Security and Safety in the Civil Aviation School.................................................. 51

6.3.3. Universidad Nacional Pedro Henríquez Ureña ................................................... 53

7. National Air Navigation Services ................................................................................... 54

7.1. Infrastructure and Personnel .................................................................................. 55

7.2. Safety Management System (SMS) ....................................................................... 58

8. Safety Audit Results and Lack Effective Implementation (EI) ........................................ 60

8.2. The Dominican Republic Results in the USOAP .................................................... 62

8.3. Overall Performance of the Dominican Republic .................................................... 63

9. Benefits of Aviation to the Dominican Republic: An Impact Evaluation Analysis ........... 65

9.1. Policy Evaluation Strategy ..................................................................................... 66

9.2. A Model for GPD per Capita .................................................................................. 68

8.3. Market Results: Microeconomic evidence .............................................................. 75

8.4. Some considerations on Taxation and Charges ..................................................... 83

8.5. Conclusion ............................................................................................................. 87

8. Policies that could further enhance the economic contribution of civil air transport in the

Dominican Republic ............................................................................................................. 88

ANNEX 1: Dominican Republic Airlines ............................................................................... 88

ANNEX 2: Impact Evaluation variables and robustness checks ........................................... 93

3

ACRONYMS

ASAs

Air Services Agreements

ASCA

Superior Academy of Aeronautic Sciences

CESAC

The Airport and Civil Aviation Safety and Security Board

DR

Dominican Republic

EI

Effective Implementation

ESAC

School of Security and Safety in the Civil Aviation

FIR

Flight Information Region

GDP

Gross Domestic Product

ICAO

International Civil Aviation Organization

IDAC

Dominican Institute of Civil Aviation

JAC

Civil Aviation Board

NCLB

No Country Left Behind

SARPs

Standards and Recommended Practices

SDG

Sustainable Development Goals

SIDS

Small Island Developing States

USAP

Universal Civil Aviation Security Program

USOAP

Universal Oversight Audit Program

4

1. Introduction

The international air transport sector, directly and indirectly, supports the employment of

62.7 million people worldwide. The sector contributes 2.7 trillion dollars in global Gross

Domestic Product (GDP), provides 4.1 billion people transport and moves more than a third

of world freight by value on 37 million flights each year.

In September 2015, Heads of State and Government adopted the United Nations

Transforming our World: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, including its 17

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and 169 targets. The Agenda is a commitment to

eradicate poverty and achieve sustainable development by 2030 worldwide. The adoption of

the 2030 Agenda was a landmark achievement, providing a shared global vision toward

sustainable development. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development called special

attention to Small Island Developing States (SIDS), as they face unique vulnerabilities in their

sustainable development.

Achieving the 2030 Agenda’s SDGs will depend on advances in mobility, including air

transport that is safe, secure, efficient, economically sustainable and environmentally

responsible. While sustainable transport and aviation do not have a specific SDG, it is widely

recognized that both are essential enablers in the achievement of the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development. In 2017, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

completed a thorough analysis of how its 2017-2019 Business Plan supports the 2030

Agenda for Sustainable Development. Through this analysis, the Organization mapped

linkages with 15 of the 17 SDGs.

In the interest of helping States to have access to the significant socio-economic benefits

of safe and reliable air transport, ICAO has launched the No Country Left Behind (NCLB)

initiative. This initiative focuses the efforts of the Organization to assist States in

implementing ICAO Standards and Recommended Practices (SARPs), which the main goal

is to help ensure that SARPs implementation is harmonized globally.

The Dominican Republic (DR), due to its outstanding aviation growth and dynamic

interaction with the States and the region, serves as a model to the Small Island Developing

States (SIDS). Other SIDS share many of the same characteristics as the DR, such as the

reliance on tourism and air transport as the primary means of transportation. During the past

12 years, the island has emerged as one of the safest and most reliable countries to fly to,

owing to a number of reforms in the aviation sector that brought the nation’s air transport into

compliance with the ICAO SARPs. These reforms, coupled with other policies to foster

tourism on the island, increased the number of passengers who fly to the Dominican

Republic, thus positively impacting island’s economy.

5

The study describes these reforms from 2006 onwards and measures, through rigorous

econometric models, the impact of these reforms on passengers flows to the State as well as

the impact on the economy as a whole. The main reforms can be summarized as:

modernization of the institutional framework, defining and separating functions between

autonomous institutions for each group of activities; liberalization of the aviation market,

fostering a free competitive market and signing air services agreements with more than 60

countries; capacity-building of public officers in order to deliver better services; modernization

of the international airports and of the air navigation system; incorporation of ICAO SARPs in

the internal legal framework; developing the Action Plan for the Mitigation of CO

2

emissions

in the aviation sector with goals and measures; and others.

This case study provides a more relevant and accurate representation of the impact of

such measures on Small Developing Island States (SIDS) as well as other small developing

economies, including meaningful insight for civil aviation planners and relevant ministries

(tourism, finance, transport) on the returns on investments generated by the civil aviation

sector.

Finally, this case study is a specific side-by-side comparison of the aviation sector before

and after the (2006) reforms were implemented. The studies also illustrate the difference

between a State that does not have political will and commitment in establishing aviation as a

national priority versus those that do.

6

2. Executive Summary

Dominican Republic statistics

The air transport market in the Dominican Republic has consistently grown by an

average of 5.52% annually over the last 20 years, making it one of the largest air

transport markets among the Caribbean countries. The number of foreign passengers

has increased at a faster pace compared to Dominican nationals, reaching 78% of

total passengers in 2018, up from 70% in 1996.

Regionally, in 2018, 63% of all passengers came from North America, while 19%

came from Europe and 6% from South America. The Caribbean accounts for 4.96%

of passengers in the air transport market in the Dominican Republic, third behind the

United States and Canada.

Only four countries make up more than 67% of passenger flows to the Dominican

Republic: the United States, Canada, Spain and Germany. The Dominican air

transport sector relies heavily on its ties to the United States. The U.S. accounted for

50% of the total flow of passengers to the island in 2018. Canada accounts for 12%,

Spain 4% and Germany 3%.

In 2018, 60 airline carriers provided regular flights to the Dominican Republic, with ten

of them making up 64% of the market share. JetBlue alone transported an estimated

21% of the total passengers to the Dominican Republic in 2018. Low-cost airlines

stood out in 2017, accounting for an estimated 45% of all passengers.

The number of passengers transported by the Dominican Republic airlines has

significantly grown between 2015 and 2018, contributing to a better connectivity

between DR and Curazao, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, British Virgin

Islands, Aruba, Antigua and Barbuda and Jamaica. They also performed charter

flights to Central and North America. The flight movements (entries and exits)

reached 5,987 operations in 2016, representing a growth of 58.9%. In 2017, the

number of flights was 9,865, a growth of 64.8%.

The 2045 forecast shows an average growth of CAGR 4% in routes from Central

America/Caribbean.

In the year 2018, there was around 126.6 million Kg. of freight traffic by air, of which,

83.3 million was exports and 43.3 million imports. This cargo translated to a total FOB

value of US$5.09 billion, which makes up 20% of the total imports and exports of the

Dominican Republic. Las Americas airport represented almost 60% of the total

imports and exports by air.

7

Since 2015, there has been steady, yearly growth in exports, around about 8%

annually, highlighted by 2016's 8.8% growth. The most exported product from the

Dominican Republic, by weight, are vegetables (70% of the total); by value, stones

and precious metals (70% of the total value). In 2018, 75% of exports from the

Dominican Republic went to North America (EUA: 64% and Canada, 11%).

There was a significant recovery on imports in 2018 after decreases in 2017. About

65% of the total imports came from United States (43%) and China (22%). Machinery

and appliances are the most imported products, by air, to the Dominican Republic,

both FOB-wise (US$806 million) and weight-wise (13.4 million kg.).

The island, which accounts for 0.43% of the total passengers in the world, ranked

47th based on 2016 results at the Global Air Connectivity Index, a World Bank

indicator that focuses on understanding the role of connectivity in economic growth

and development. About 62% of total passengers used a direct flight to travel to DR,

36% made one stop and 2%, two stops, in 2016.

DR has 36 airports, aerodromes and runways, both public (direct administration and

concessions) and private. The international airports are administered by the private

sector, either through concessions (five) or are privately-owned (three). By 2018,

passengers flew via 242 direct routes from/into 38 countries/territories provided by 43

airlines through its 7 operational international airports.

The traffic is concentrated in two main airports: Punta Cana (PUJ) and Santo

Domingo (SDQ). Around 80% of passengers originating in the Dominican Republic

departed from these two airports in 2017, through 50% of the total routes.

Policy Reforms

DR enacted Law No. 491-06 in December 2006, modernizing legislation to cope with

the new aviation landscape, followed by two amendments: Law 67-13 and Law 29-18.

The relevant reforms in the aviation sector are: (i) a set of strong institutions to define

the air transport policies and to establish the technical and economic regulations of

civil aviation, air traffic control, investigation of accidents and sector oversight. The

objective is to separate functions among autonomous institutions to avoid conflict of

interests; (ii) institutions to define the air transport policies and to establish the

technical and economic regulations of civil aviation, air traffic control, investigation of

accidents and sector oversight; (iii) More flexibility for foreign operators and relaxation

of ownership requirements for national operators.

8

Until 2007, the Dominican Republic had signed bilateral agreements with 19

countries, most of them traditional (limited frequencies and routes). However, Law

491-06 established the liberalization of air services in the State. By giving the Civil

Aviation Board (JAC, in the Spanish abbreviation) the mandate to sign Air Services

Agreements (ASAs) on behalf of the State and a technical staff to carry out the

activities, the new law boosted the number of agreements and moved towards more

liberal agreements signed between the Dominican Republic and other countries,

reaching agreements with a total of 66 countries.

JAC also accepted more code share agreements after the reforms, as a way to bring

about more routes to the State. Currently, there are 15 active code share

agreements, which provide 25 routes from Panamá, Spain, the United States,

Guadeloupe, Guyana, and the United Kingdom, involving 15 airlines.

The Dominican Republic joined the ICAO-UE capacity building program for CO

2

mitigation from international aviation. The State defined an Action Plan with goals and

mitigation measures. Between 2012-2018, the Dominican stakeholders invested

around USD 13 million in measures to mitigate CO

2

emissions, including solar power

plants, equipment to improve energy efficiency in the airports, LED lights, more

efficient refrigeration systems, implementation of Preconditioned Air (PCA) units and

electronic Ground Power Units (GPU) to reduce the use of auxiliary power units

(APU) and the partial implementation of the Air Traffic Flow Management (ATFM)

concept in the main building of Air Navigation Services Norge Botello. ICAO-UE

measured 16.800 CO

2

fewer tons of emissions from international flights and airports

compared to the 2018 baseline (without project scenario).

Security and Safety Oversight: Policies and Capacity Building

Similarly, Law 188-11 changed the civil aviation safety and security oversight in the

Dominican Republic. These changes included the development of a modern system

of sanctions for violations and acts of disobedience.

The Airport and Civil Aviation Safety and Security (CESAC) board has released the

National Plan for Security and Safety in the Civil Aviation, which led to a group of

reforms, such as the implementation of a data center, new technologies for

inspections, and a video system for airport oversight and simulation.

In 2014, the Dominican Republic established its primary law and regulations to certify

airplanes ground handling services companies. By now, 28 companies have been

identified, and five were certified. 18 more are currently going through the certification

9

process under RAD 24 (Dominican Aviation Regulation, in the Spanish abbreviation)

and 10 have expressed interest but have not started the process.

Along the same lines, through the Superior Academy of Aeronautic Sciences (ASCA),

the Dominican Republic has trained 9,265 students under more than 100 academic

courses from 2008-2018. The academy also trained 291 students on Air Traffic in

Aerodromes and Aeronautic Administration, since 2013. Furthermore, ASCA provided

courses for students in many other countries in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Through the School of Security and Safety in the Civil Aviation (ESAC), the

Dominican Republic trained 6,500 professionals on security and safety in civil

aviation, and 4525 professionals through 252 courses, from 2009-2018. Among these

students, 196 are foreigners from 17 different countries.

Under this new reform framework, and due to the commitment of the Dominican

Republic toward security issues, major progress was made in the Universal Civil

Aviation Security Program (USAP) from 76.46% to 96.98% in 2017, an increase of

20.52 percentage points, reaching high marks in terms of airport security and civil

aviation.

Air Navigation Systems

The FIR Santo Domingo (MDCS) has a dimension of 172,578 km

2

, surrounded by the

FIRs of Miami (KZMA), San Juan (TJZS), Curazao (TNCF) and Port-au-Prince

(MTEG).

The Air Traffic Flow Management Unit was created under the Santo Domingo Area

Control Center, with a staff of 13 specialists, to monitor and evaluate the traffic

situation in the airports and the Santo Domingo Flight Information Region (FIR),

generating deliverables designed for the optimal execution of air flows.

The Air Navigation System is staffed by more than 600 air navigation service provider

personnel, 266 aviation technical operators and 334 air traffic controllers. The ANS

personnel, spread throughout the different air navigation facilities, supported air

navigation services for 215,770 air operations during 2018.

The Dominican Republic created the Department of Safety Management, which is a

specialized technical body responsible for the implementation of an SMS for air

navigation services as well as the subsequent continuous operation of said system.

The Dominican Republic is upgrading its Aviation System Block, starting from Block

0, which has the capacities ready to be implemented with supporting documents such

as standards, procedures, specifications and training materials. The State expects to

10

start upgrading Block 1 in 2019, Block 2 in 2025 and Block 3 in 2031, with ICAO's

support.

Safety Audit Results and Lack of Effective Implementation

In 1993, the United States Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) downgraded the

Dominican Republic to Category II. Under the new aviation law approved in the

Dominican Republic (2006), and the different improvements obtained from the new

reform framework, the FAA upgraded the Dominican Republic aviation safety rating to

Category I in 2007.

The first audit under the Universal Safety Oversight Audit Program (USOAP) in the

Dominican Republic was carried out in January 2009, with missions to validate the

corrective measures in 2016 and 2017. The State has achieved great results in the

ICAO's USOAP, improving the Effective Implementation (EI) from 85.98% (2009) to

90.52% (world average is 66.32%). With these results, the Dominican Republic ranks

in the top 5 States in the North America, Central America and Caribbean Region

(NACC) in the safety oversight arena (top 4 of 22 in NACC region).

The Impact of Air Transport Reforms in the Dominican Republic Economy

Our macroeconomic model estimated a 15.5% increase in GDP per capita between

2006-2012, which can be translated in USD 607 per capita of income increase.

The microeconomic model estimated an increase between 23% and 27% in the

participation of passengers going to Dominican Republic from the U.S. over

passengers going to other destinations. Moreover, due to the policy improvements,

the increase of U.S. tourists to the DR increased tourism spending by USD 836

million to 1.016 billion between 2006-2012. The results show a causal relationship

between the reforms and the increase of passengers, thus impacting positively the

economy.

Using a conservative estimate, the total net benefit to Dominican Republic in the

period of 2006-2012 attributable to the policy is USD 837 million through American

tourist spending, and USD 78 million in taxes charged by the State to non-residents,

reaching a total of USD 915 million. The contribution of taxation to the economy

(GDP) of Dominican Republic is significant. Estimates indicate that for the year 2017,

taxation contributed around USD [non-residents 80 unit tax] 490 million to the DR

economy.

11

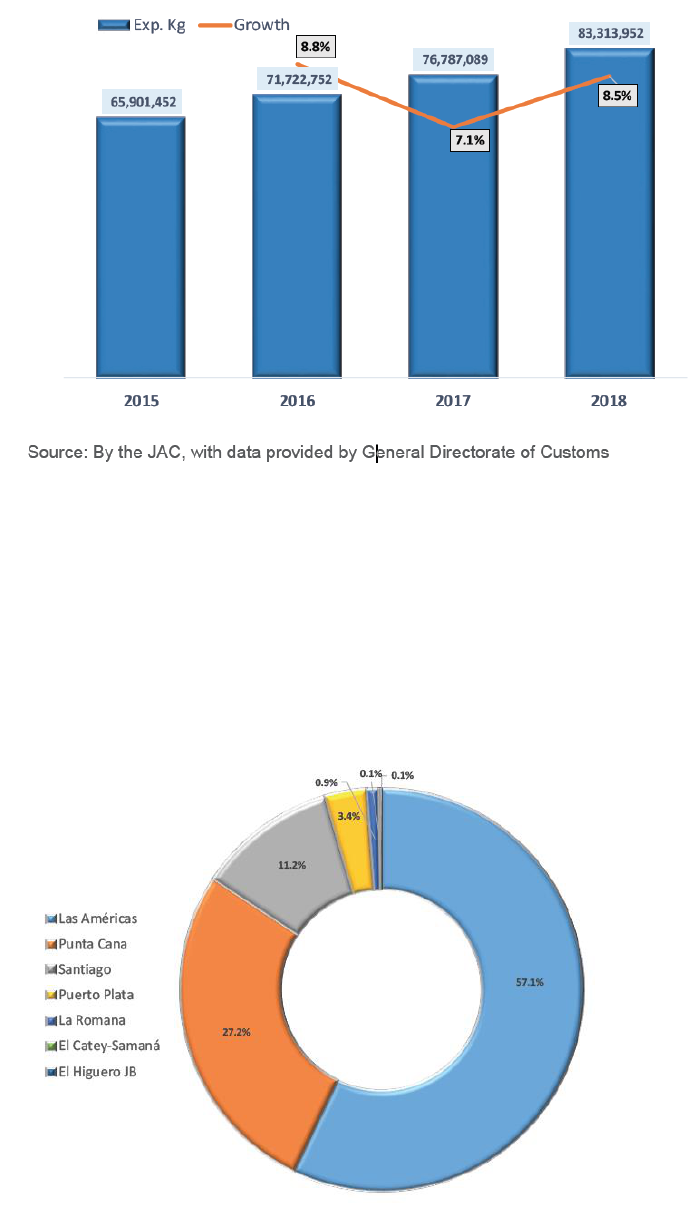

3. State Profile

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC

Socioeconomic Indicators

Aviation Indicators

Population: 10.88 million

Surface area: 48,671 square kilometers

Population Density: 224 people per sq km

Category: Small Island Developing State

GDP: 75.93 billion USD (2017)

GDP per capita: US$ 7,052.26 USD (2017)

Upper middle-income developing State (Word

Bank)

Average growth (2000-2016): 4.9%

Doing Business Ranking (2018): 99

th

(World Bank)

Global Competitiveness Index (2017-

2018): 3.9 out of 7 (104

th

out of 137) (World

Economic Forum)

Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Index

(2017): 76

th

(World Economic Forum)

Logistics Performance Index (2018): 2.66

(87th).

Number of passengers: 13,751,481 (2017)

Average growth total pax (1996-2017):

5.28%

Global Air Connectivity Index (2106): 0.41

(rank 47

th

- World Bank).

Air Liberalization Index (2011): 23 out of

50 (WTO).

Global Competitiveness Index - Quality of

Airport Infrastructure (2017-2018): 4.8 out

of 7 (50

th

) (World Economic Forum)

Airport Infrastructure:

36 airports, aerodromes and runways;

8 international airports (7 operative)

4 public airports (managed by private

firms through concessions)

3 private airports (Punta Cana, La

Romana y El Cibao)

1 national domestic airports;

1 military airport;

7 domestic aerodromes;

20 aerodromes for aerial work

(agriculture aerial spraying)

Effective Implementation (EI) of ICAO

USOAP: 90.52% (4

th

in the region, 2018).

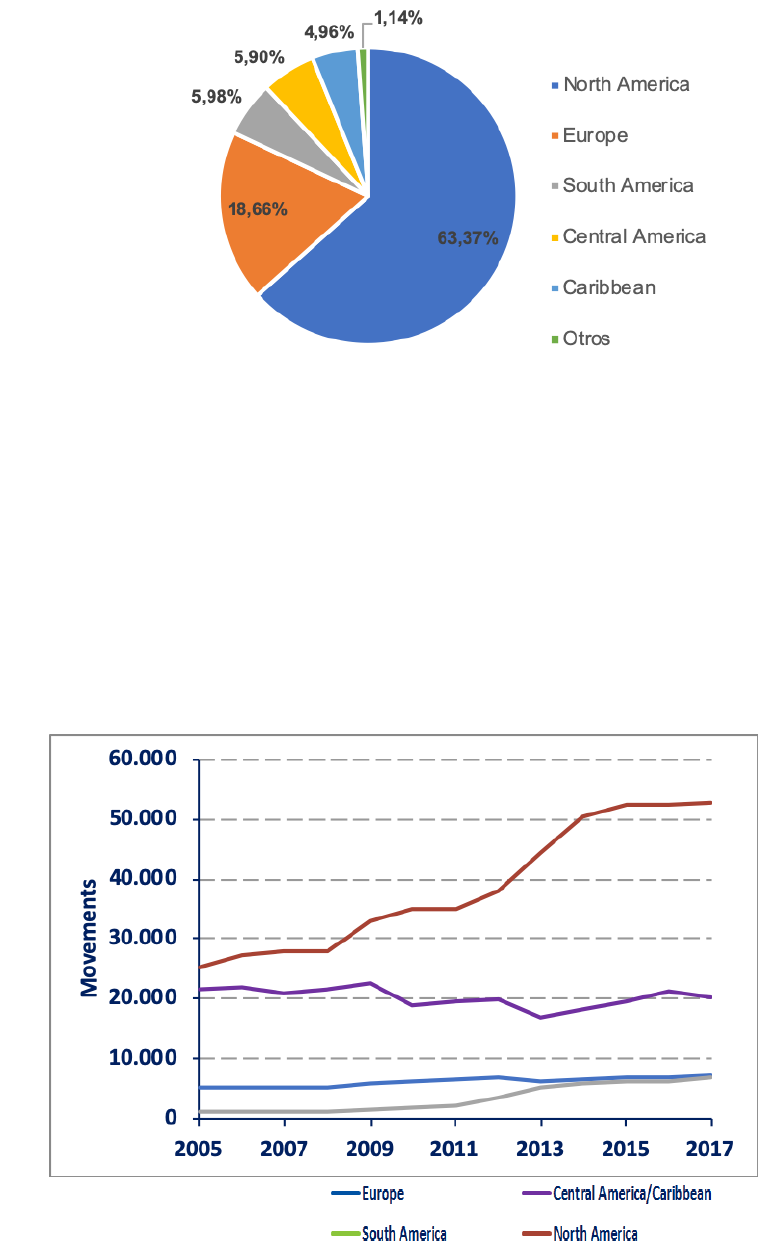

Chart 1: Tourist Arrivals by Air (%) ....................................................................................... 12

Chart 2: The evolution of the air transport market in the Dominican Republic, 1996-2018 ... 13

Chart 3: Air Transport Market by Region in Dominican Republic, 2018 (total pax) ............... 14

12

Chart 4: Number of scheduled flights in the Dominican Republic, 2005-2017 ...................... 14

4. State of Air Transport and Connectivity

4.1. State of Air Transportation: general statistics, main destinations and

airlines

The air transport market in the Dominican Republic has consistently grown by an

average of 5.52% annually over the last 20 years, making it one of the largest air transport

markets among the Caribbean countries. The number of foreign passengers has increased

at a faster pace compared to Dominican nationals, reaching 78% of total passengers in 2018

up from 70% in 1996. Moreover, 90% of tourists arrive by air, indicating the importance of

aviation for tourism on the island, as shown in the chart 1.

Chart 1: Tourist Arrivals by Air (%)

The chart 2 shows the evolution of the air transport market in the State. There are

only two points where the market showed slight drops in the rate of growth, both related to

major global events: 2001-2002, due to the terrorist attacks on 09/11, and 2008-2009, due to

the global economic crisis. However, the Dominican Republic quickly adapted to these short-

term setbacks by redirecting destination-marketing efforts to alternative source markets with

13

similar spending and travel habits, such as Canada, mitigating the effects of the crisis (WEF,

2011).

Chart 2: The evolution of the air transport market in the Dominican Republic, 1996-2018

Source: JAC

Regionally, in 2018, 63% of all passengers came from North America, while 19%

came from Europe and 6% from South America, as described in the chart 3. While the

numbers are skewed towards the United States — which captures most of the passengers of

North America — in South America, the passengers are divided nearly equally between

Brazil, Argentina, Chile and Colombia. In Europe, the largest number of passengers come

from Germany, Spain, Italy and France. The Caribbean accounts for 4.96% of passengers in

the air transport market in the Dominican Republic.

Average growth

(foreigners): 5.52%

Application of new aviation

reforms

14

Chart 3: Air Transport Market by Region in Dominican Republic, 2018 (total pax)

Source: JAC, OAG

The number of scheduled flights (movements) has also grown from 2005 to 2017,

especially from North America, as shown in chart 4:

Chart 4: Number of scheduled flights in the Dominican Republic, 2005-2017

Source: JAC, OAG

15

Only four countries make up more than 67% of passenger flows to the Dominican

Republic: the United States, Canada, Spain and Germany. The Dominican air transport

sector relies heavily on its ties to the United States. The U.S. accounted for 50% of the total

flow of passengers to the island in 2018. The average growth between 2005-2017 was

5.96% annually. The only drop occurred between 2007 and 2008, due to the 2008 financial

crisis in the U.S. Chart 5 shows the growth trend between the two countries.

The main inbound flights left and returned to the cities of New York (about 39% of

total U.S. passengers), Miami (11%), Fort Lauderdale (7%) and Atlanta (6%), arriving at the

airports of Las Americas (Santo Domingo), Punta Cana and Del Cibao. It is important to note

that eight of top 10 outbound routes from Dominican Republic are to United States in 2018.

Chart 5: Evolution of the air transport market in Dominican Republic (2005-2018), United States

(pax)

Source: JAC

Canada ranks second in terms of air transport flows to the Dominican Republic. The

State accounted for 12% of the total flow of passengers to the island in 2018. The average

growth rate between 2005-2018 was 6.36% annually. The main flights left and returned to

the cities of Toronto (45% of all Canadian passengers) and Montreal (30%) to Punta Cana

and Puerto Plata.

1

KJFK (John F. Kennedy International Airport); KMIA (Miami International Airport); KATL (Atlanta

International Airport); KEWR (Newark International Airport); LFLL (Fort-Lauderdale International

Airport); MDSD (Santo Domingo International Airport); MDST (Cibao International Airport); MDPC

(Punta Cana International Airport).

Route

1

Total pax, 2018

% of total U.S. pax

(Departures+Arrivals)

KJFK - MDSD

952,038

12,99%

KJFK - MDST

950,773

12,98%

KJFK - MDPC

490,600

6,70%

KMIA - MDSD

437,769

5,98%

KATL - MDPC

436,058

5,95%

KMIA - MDPC

380,963

5,20%

KEWR - MDPC

268,416

3,66%

KFLL - MDSD

261,433

3,57%

KFLL - MDPC

227,941

3,11%

KEWR -MDST

213,337

2,91%

TOTAL

4,619,328

63,05%

US TOTAL

7,326,465

Average growth: 5.96%

16

Chart 6: The evolution of the air transport market in the Dominican Republic (2005-2018),

Canada

Source: JAC

Spain is the third State in passengers flows to the Dominican Republic, accounting for

approximately 4% of all passengers in 2018. Between 2007 and 2013, the number of

passengers from Spain dropped consistently, but recovered from 2014 onwards. The main

flights departed from two cities, which account for 97% of all passengers: Madrid-Santo

Domingo and Madrid-Punta Cana.

2

CYYZ (Toronto Pearson International Airport); CYUL (Montreal International Airport).

Route

2

Total pax,

2017

(Departures+Arrivals)

% of total

CAN pax

CYYZ - MDPC

629,363

35%

CYUL - MDPC

402,057

23%

CYYZ – MDPP

185,500

10%

CYUL - MDPP

113,234

7%

TOTAL

1,326,819

74%

CAN TOTAL

1,326,819

Average growth: 6.36%

17

Chart 7: The evolution of the air transport market in the Dominican Republic (2005-2018), Spain

Finally, Germany was the 4

th

State in terms of passengers flows to the Dominican

Republic, accounting for approximately 3% of all passengers in 2018, a drop from 2017.

Between 2005 and 2009, Germany registered a drop on the number of passengers to the

Dominican Republic, but has recovered between 2012 to 2016. Germany registered an

average growth of 0.04% between 2005-2018. The main flights to the Dominican Republic

left and returned to the cities of Frankfurt (EDDF) (24%), Dusseldorf (EDDL) (22%) and

Cologne (EDDK) (15%) to Punta Cana, in 2018.

Chart 8: The evolution of the air transport market in the Dominican Republic (2005-2017),

Germany (pax)

Source: JAC

Route

Total pax,

2018

% of total SPA pax

(Departures+Arrivals)

LEMD-MDSD

377,091

61%

LEMD-MDPC

225,221

36%

TOTAL

602,312

97%

TOTAL SPA

622.681

Route

Total pax, 2017

(Departures+Arrivals)

% of total

GER pax

EDDF - MDPC

109,757

24%

EDDL – MDPC

101,363

22%

EDDK - MDPC

83,793

15%

TOTAL

279,033

59%

Average growth: 0.04%

Average growth: -0.26%

18

In 2018, 60 airline carriers provided regular flights to the Dominican Republic, with ten

of them making up 64% of the market share. JetBlue alone transported an estimated 21% of

the total passengers to the Dominican Republic in 2018. The low-cost airlines

3

stood out in

2018, accounting for an estimated 45% of all passengers.

Chart 9: Market share of air transport by airlines, Dominican Republic, 2018

Source: JAC, OAG

3

ICAO defines low cost carrier as an air carrier that has a relatively low-cost structure in comparison

with other comparable carriers and offers low fares and rates.

19

Forecast for Central America/Caribbean

4

The forecast shows an average growth of CAGR 4% in the routes from Central

America/Caribbean. CAGR 3.6% in the RPK from Central America/Caribbean – North

America for 2015-2045, still ranking first in terms of RPK (billion). The largest growth will take

place in Latin America/Caribbean – Central Southwest Asia (CAGR 5.3%).

Chart 11: ICAO Long-Term Traffic Forecast (2015-2045)

Source: ICAO

4

The Dominican Republic is part of this region.

20

4.2. Dominican Republic Airlines

The number of passengers transported by Dominican airlines has significantly grown

between 2015 and 2018, contributing to better connectivity between the DR and Curazao,

Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Saint Martin, British Virgin Islands, Aruba, Antigua and Barbuda

and Jamaica. They also performed charter flights to Central and North America.

In 2016, PAWA Dominicana started operating in the State, bringing some dynamism

to the airline market. PAWA Dominicana contributed to a 337% growth in the number of

passengers transported by national airlines compared with 2015, and 147% compared with

2017. The flight movements (entries and exits) reached 5,987 operations in 2016,

representing a growth of 58.9%. In 2017, the number of flights was 9,865, a growth of 64.8%.

However, PAWA ceased operations in the beginning of 2018, negatively impacting the

market but also creating space for new national operators.

The market of national airlines is dominated by Air Century S.A., a Dominican private

firm, which operates 16 regular routes and charter flights in the region. In 2016, Air Century

grew 151% in number of flights made, followed by 85.3% growth in 2017 and 82.4% growth

in 2018. Sky High Aviation, another Dominican airline company, has expanded its operations

since 2016, servicing the British and Dutch Caribbean. The company is planning to operate

larger airplanes in the future. The State has granted authorization for a new operator,

Servicios Aéreos GECA, S.A., to operate from the airport Jose Francisco Peña Gómez to

Puerto Príncipe and Haitian Cape in Haití, Habana, Santiago and Camaguey in Cuba,

Agudilla in Puerto Rico, Curazao, Aruba and Sant Martín, Tórtola, Kingston and

Providenciales. Annex 2 shows detailed information about routes and companies.

Dominican Republic Airlines

Flight movements, 2015-2018

Airlines

2015

2016

2017

2018

Helicópteros Dominicanos S.A./Helidos

1,017

1,594

2,211

2,390

Air Century, S.A./ACSA

651

1,452

2,098

3,004

Pawa Dominicana

470

2,040

3,685

224

Servicios Aéreos Profesionals, S.A.

471

400

1,0515

1,947

Sky High Aviation Services, S.R.L

307

343

698

2,123

Aerolíneas Mas S.A.

719

4

-

-

Aerolíneas Santo Domingo S.A.

109

42

39

34

Dominican Wings, S.A (Dw)

-

58

88

-

Tropical Aero Servicios S.R.L (Tas)

15

49

1

-

Republic Flight Lines, S.R.L

-

3

34

1

Aeronaves Dominicana//Aerodomca

6

-

3

-

21

Aerojet Services, S.A.

-

2

2

-

Transporte Aéreo S.A.

2

0

0

0

TOTAL

3,767

5,987

9,865

9,723

Source: JAC/IDAC

Dominican Republic Airlines

Number of passengers, 2015-2018

Airlines

2015

2016

2017

2018

Pawa Dominicana

11,477

114,998

288,530

19,330

Air Century, S.A./ACSA

4,001

10,075

18,673

34,061

Sky High Aviation Services, S.R.L

2,871

3,243

7,940

30,753

Servicios Aéreos Profesionals, S.A.

2,490

2,406

9,875

18,970

Dominican Wings, S.A (Dw)

-

2,204

6,657

-

Helicópteros Dominicanos S.A./Helidos

1,082

1,688

2,338

3,456

Aerolíneas Mas S.A.

8,109

39

-

-

Aerolíneas Santo Domingo S.A.

784

257

197

132

Republic Flight Lines, S.R.L

-

10

126

2

Tropical Aero Servicios S.R.L (Tas)

30

78

2

-

Aerojet Services, S.A.

-

5

3

-

Aeronaves Dominicana//Aerodomca

1

-

1

-

Transporte Aéreo S.A.

1

-

-

-

TOTAL

30,846

135,003

334,342

106,704

Source: JAC/IDAC

4.3. Cargo Statistics

Cargo Flights

5

In the Dominican Republic, as is standard global practice, most of the freight traffic by

air is on combined flights (passengers, freight and mail). Nevertheless, in 2018, there were

4,538 cargo-only flights, about 6 per day on average. More than 60% (2,789) were charter

flights and the rest scheduled (1,749).

5

This section was copied from the Air Transport Statistics Report: Dominican Republic 2018,

produced by JAC.

22

Chart 12: Dom. Rep. Cargo-only flights stages on scheduled and non-scheduled flights 2018

Freight traffic

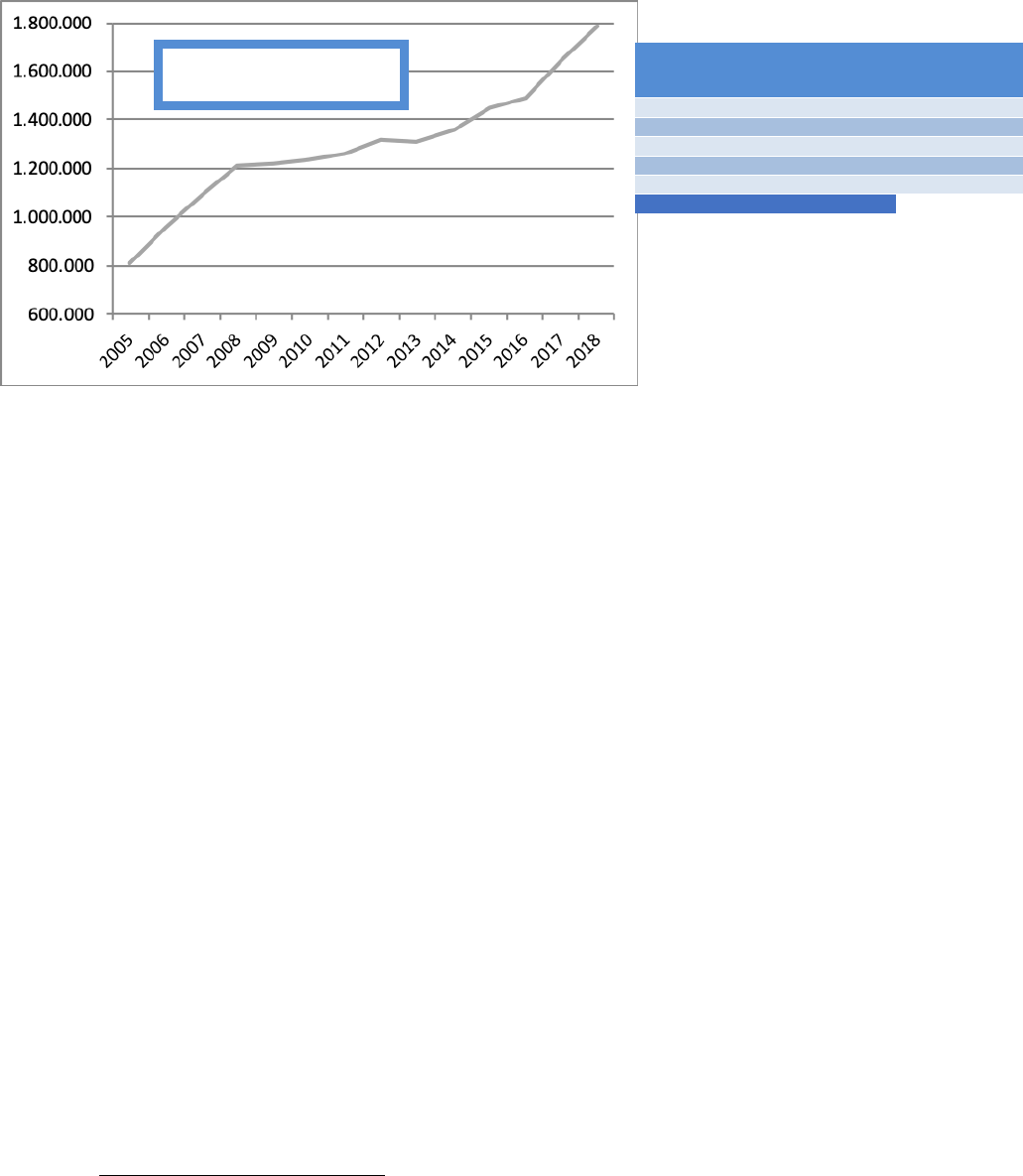

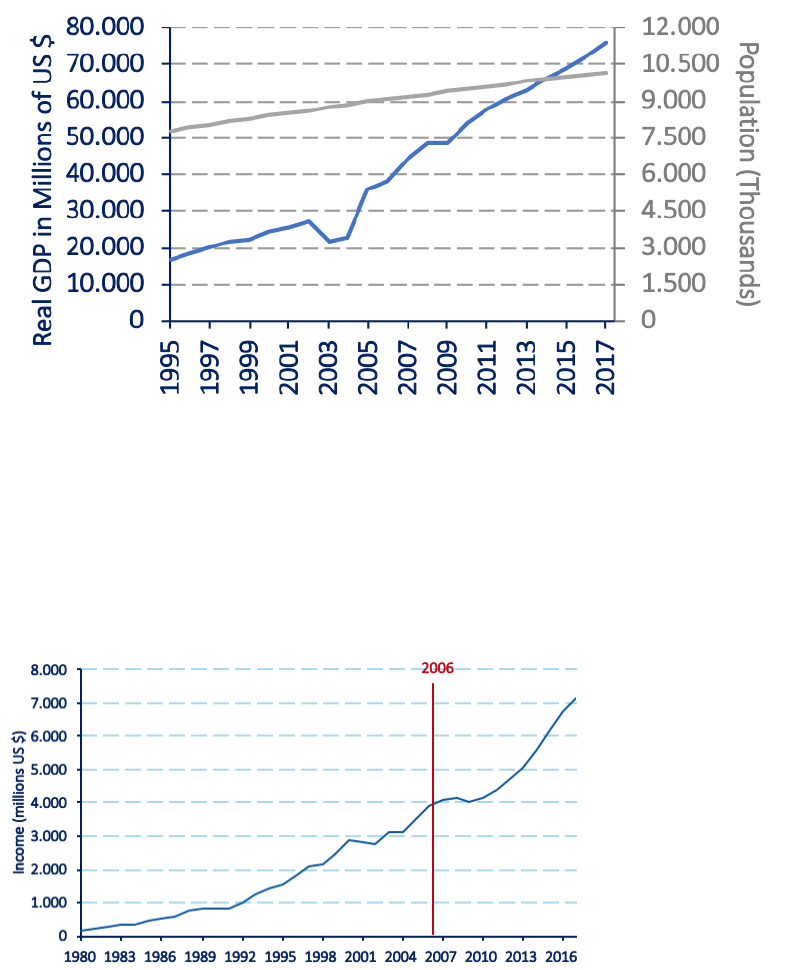

In 2018, 126,647,638 Kg. of cargo was moved by air, of which, 83,313,952 were

exports and 43,333,686 were imports. This translates to a total FOB value of USD

5,092,549,832, which makes up about 20% of total value of imports and exports of the

Dominican Republic. In regards to FOB, imports were much more valuable than exports, with

the former averaging FOB USD 55/KG, while the latter averaged USD 32.68/KG.

Exports – 2014-2018

83,313,952 kg of goods were exported in 2018, representing 8.5% growth from 2017.

As illustrated chart 13, there was steady yearly growth in exports since 2015, approximately

8% annually with a high-point of 8.8% growth in 2016.

23

Chart 13: Dominican Republic Exports 2015-2018

95% of the exports from the Dominican Republic departed from the Las Americas

JFPG, Punta Cana and Santiago airports, led by Las Americas JFPG with 47,601,023 Kg.

(57% of the total).

Chart 14: Dominican Republic Exports - Airports 2018

In 2018, 75% of exports from the Dominican Republic went to North America;

53,289,692 kg to the USA and 8,684,170 kg to Canada. Exports towards Europe also played

24

an important role, especially to France, the UK and Germany; these three destinations

accounted for 11% of total exports.

Chart 15: Dominican Republic Exports by State of destination 2018

The most exported product from the Dominican Republic, by weight, are produce

items, accounting for 56,464,527 kg.; this number represents almost 70% of the total weight

exported. By FOB standards, the most exported product from the State were fine pearls,

stones and precious metals, valued at USD 1,934,796,379, more than 70% of the total export

value.

Imports (2015-2018)

There was a significant recovery on imports in 2018 after a downturn in 2017. The

recovery represented a (5.8%) rate of growth in imports, +7.1 more than 2017 (-1.3%).

25

Chart 16: Dominican Republic Imports 2015-2018

99% of the imports to the Dominican Republic in 2018 came through the Las

Americas, Del Cibao and Punta Cana airports; Las Americas led the way receiving over 25

million Kg. in imports, accounting for more than half of the total amount.

Chart 17: Dominican Republic Imports - Airports 2018

26

The majority of imported goods to the Dominican Republic in 2018 came from North

America or Asia, specifically the USA, 18,681,645 Kg, and China, 9,546,839 Kg. These two

countries account for 65% of total imports.

Chart 18: Dominican Republic Imports by State of destination 2018

Machinery and appliances are the most imported products, by air, to the Dominican

Republic, both FOB-wise (USD 806,290,488) and weight-wise (13,435,975 kg.). Chemical

Industry products are the 3rd most imported product to the Dominican Republic in regards of

weight, but its's the most expensive imported product among the top 5 listed below with an

average value of USD 105/KG.

27

4.4. Air Connectivity: Direct Routes, Destinations and Airlines

As a Small Island Developing State (SIDS), air and maritime connectivity is crucial to

the development of tourism and international trade in the Dominican Republic, as they are

the main drivers of the State's GDP growth. Air connectivity is defined as the movement of

passengers, mail and cargo using the minimum number of transit points, i.e. making trips as

short as possible and at the lowest price. The figure below outlines the major variables

impacting air connectivity.

Figure 1: Variables of Air Connectivity

The DR, which accounts for 0.43% of the total passengers in the world, ranked 47th

based on 2016 results at the Global Air Connectivity Index, a World Bank indicator that focus

on understanding the role of connectivity in economic growth and development. About 62%

of total passengers arrived via direct flight to the State, while 36% made one stop and 2%,

two stops. States like France, the United Kingdom and the United Arab Emirates are well-

connected, for example, with about 85% of their passengers arriving via direct flights. The

figure below describes the passenger traffic composition of the State in 2017.

Figure 2: Passenger Traffic Composition of Dominican Republic, 2017

Source: ICAO-ICM Global Air Transport Diagnosis using Marketing Information Data Transfer (MITD) Data

28

By 2018, passengers flew via 242 direct routes from/into 38 countries/territories

provided by 43 airlines, through the DR’s 7 operational international airports. Most of the

direct routes connect the Dominican Republic to United States (29%), Canada (22%),

Germany (8%) and France (5%), accounting for 64% of the total. The map below shows the

main direct routes with connections beyond non-stop cities.

Figure 3: Air Connectivity of Dominican Republic, 2017

Source: ICAO-ICM

As mentioned before, the optimal use of the airport system is one of the important

elements of the DR’s advantageous air-connectivity. The State has 36 airports, aerodromes

and runways, categorized by public (direct administration and concessions) and private.

29

Figure 4: Main Airports and Heliports

Source: IDAC

The table below lists the main international airports. These are administered by the private

sector, either through concessions (five) or are privately-owned (three). It is important to note

that concessions were granted for the same firm, Aeropuertos Dominicanos Siglo XXI

(Aerodom), which has been part of the VINCI Airports group since 2016. Though the airports

are managed by private firms, they need to comply with international security norms

established by Law 491-06 by applying for an air-operating certificate, granted by the

General Department of Civil Aviation.

Table 1: International Airports in Dominican Republic, 2017

Name

Since

Pax flow and Connectivity

(2018)

Management

Technical

Information

Punta Cana International

Airport (PUJ/MDPC)

1983

Passengers: 7,852,417

(2nd in the Caribbean; 24th

in Latin America).

- 109 direct routes from/to

33 countries/territories

provided by 40 airlines.

- Charters from 46

countries/territories.

Private

(Grupo Punta Cana)

- Two runways

(3,100 x 45)

ICAO RC: 4E

- two terminals

Las Americas JFPG

(Santo Domingo –

SDQ/MDSD)

1959

Passengers: 3,781.,25

(5th in the Caribbean)

- 54 direct routes from/to 26

countries/territories

provided by 30 airlines

Public (concession in

2000 for 30 years to

Aerodom/VINCI

Airports)

- one runway (3,354

x 60)

ICAO RC: 4E.

- two terminals

30

- Charters from 34

countries/territories.

Cibao International Airport

(STI/MDST)

2002

Passengers: 1,598,569

- 15 direct routes from/to 6

countries/territories

provided by 10 airlines.

- Charters from 8

countries/territories.

Private (Aeropuerto

Internacional de

Cibao S.A.)

- one runway (2,620

x 45)

ICAO RC:4D

- two terminals

Gregorio Luperón

International Airport

(Puerto Plata,

POP/MDPP)

1979

Passengers: 873,481

- 36 direct routes from/to 9

countries/territories

provided by 12 airlines.

- Charters from 23

countries/territories.

Public (concession in

2000 for 30 years to

Aerodom/VINCI

Airports)

- one runway (3,081

x 46)

ICAO RC:4E

- one terminal

La Romana International

Airport (LRM/MDLR)

2000

Passengers: 197,547

- 14 direct routes from/into

9 countries/territories

provided by 18 airlines.

- Charters from 38

countries/territories.

Private

(Central Romana

Corportation, LTD)

- one runway (2,950

X 45)

ICAO RC:4D

- one terminal

Samaná El Catey/Juan

Bosch International

Airport (AZS/MDCY)

2006

Passengers: 165,419

- 12 direct routes from/into

5 countries/territories

provided by 8 airlines.

- Charters from 10

countries/territories.

Public (concession

for 30 years to

Aerodom/VINCI

Airports)

- one runway (3000

x 45)

ICAO RC:4E

- one terminal

La Isabela Dr. Joaquín

Balaguer International

Airport/ El Higuero

(JBQ/MDJB)

2006

Passengers: 47,779

- 7 direct routes from/into 4

countries provided by 4

airlines.

- Charters from 36

countries/territories.

Public (concession

for 30 years to

Aerodom/VINCI

Airports)

- one runway (1659

X 30)

ICAO RC:3C

- one terminal

María Montez

International Airport

(Barahona, BRZ/MDBH)

1996

- Did not perform any

international flights in 2018.

Public (concession in

2000 for 30 years to

Aerodom/VINCI

Airports)

- one runway (3000

X 45)

One terminal

Not operating

Source: IDAC

The government of the Dominican Republic manages most of the domestic airports,

with the exception of the Arroyo Barril Airport, which is operated by Aerodom. As illustrated in

table 1, traffic is concentrated in two main airports: Punta Cana (PUJ) and Santo Domingo

(SDQ). Around 80% of passengers originating in the Dominican Republic departed from

these two airports in 2017, via 50% of the total routes.

The international airports are distributed across different tourist destinations in the

State in order to decentralize services provided by the Santo Domingo Airport, which still is

the most important access point for international tourists to the Dominican Republic. The

Puerto Plata Airport was built in 1979, to allow tourist access to the beaches in the North

region, and of the Punta Cana International Airport was built in 1983, to improve access to

the Eastern region. In the capital area, the La Isabela Airport, formerly la Herrera,

complements the Santo Domingo Airport as a more affordable airport for Caribbean airlines

31

to fly to Haiti, Puerto Rico and Jamaica. The airport is also used for charter flights and even

for some international and domestic flights.

During the 2000s, due to the improvement of road transportation and investments in

the tourism sector, the airport system incorporated two new airports: La Romana

International Airport (2000), which serves the southeastern coast of the Dominican Republic;

the Cibao International Airport (2002), which connects the second biggest city of Dominican

Republic to the world and serves Dominicans who reside in the U.S., Cuba, Panama, Haiti,

Puerto Rico, Turks and Caicos Islands and the Dutch Antilles; and finally the Juan Bosch

International Airport (2006), that serves the Las Terrenas and Las Galeras beaches. The

María Montez International Airport, which provides access to the southwest region, one of

the most beautiful tourist destinations in the State, does not yet receive international flights.

This airport is two hours from the Haitian border. Since 2017, the private sector has invested

in developing the La Ciniega area, building hotels and summerhouses and providing asphalt

road access from the airport to the beaches. This investment will likely increase the number

of international tourists to the area starting in 2019-2020.

Over the next few years, the Dominican Republic will move to an organic airport

system in which each airport transitions from a regional monopoly to a more competitive

environment where tourists and other customers have multiple options for travel. For many

years, a given airport was the only safe and fast mode to access some beaches, but this is

no longer the case. The intermodality strategies between port (cargo and passengers), roads

and airports will be key to creating a more efficient use of the airports.

4.5. The Caribbean: Regional Benchmarking

The Caribbean is the region with the largest travel and tourism (T&T) contribution to

the GDP in the Americas, registering around 14% (the average for Latin America is 8.9%),

according to ALG (2014). The region receives around 21.2 million tourists annually, which

makes up a 2% share of world tourism. The forecast predicts that the T&T contribution will

grow 3.7% annually over the next decade, accounting for 52 million jobs.

Air transport is key for the tourism industry and for national and regional integration,

because remote and or island nations rely on this mode of travel almost exclusively. Most

islands in the Caribbean are above the world average in terms of air transport seats per

capita compared to income per capita. In the Americas, the Caribbean ranks third in seat

capacity and first in terms of international airlift capacity (2013). Most of the traffic for

Caribbean territories is inbound (tourists visiting the countries), and the outbound traffic is

32

weak from most of territories. The chart below shows the distribution amongst Latin

American countries and the Caribbean.

Chart 19: Schedule seats capacity - million seats, 2013

Source: ALG, 2014.

While the world average of international tourist arrivals has grown 3.8% (CAGR 2005-

13), the Caribbean air transport market has experienced one of the slowest capacity growth

rates in recent years (1.5%, CAGR 2005-2013). Moreover, there is uneven growth across

the territories of the region. Islands with more tourists have, in general, more positive

evolution (ALG, 2014). As we can see at the chart below, the Dominican Republic is the first

in the region, accounting for 22% of total tourist arrivals in the Caribbean in 2013.

33

Chart 20: Tourist arrivals by State in the Caribbean region, 2013

Source: ALG, 2014 (with data from UNWTO)

In terms of origin markets, North America accounts for two thirds of the incoming

tourists in the region, showing an increase of CAGR 1.5% between 2008 and 2012, while

European tourist arrivals have decreased by CAGR 1.9% during the same period. The routes

from North America to the Caribbean are very concentrated: the five top North American

airports with flights to the Caribbean account for 75% of the routes offered to the region,

while the top 10 accounts for 90%. Miami, New York, Toronto, Fort Lauderdale and Atlanta

are the main gateways to the Caribbean.

Surprisingly, the Latin American market weight increased by CAGR 8% between

2008 and 2012, accounting for 6.6% of the total market. Domestic & Intra-Caribbean markets

have experienced continuous capacity reduction, with an average decrease of 3.1% (CAGR

2005-2013) (ALG, 2014), and a 2.3% CAGR reduction in the number of routes. The region

has a large airport network (67 with more than one weekly international flight), but limited

traffic volumes. The top ten airports account for 57% of the region's capacity and the top 20

account for nearly 80%.

34

Chart 21: O&D Caribbean air traffic flows, 2013

Source: ALG, 2014.

Finally, Airbus predicted significant growth for international Caribbean traffic in the

next 20 years (CAGR 2013-2032), but it is pessimistic about Intra-Caribbean traffic. Airbus

expects a growth rate of around 3% per annum for the countries that have already reached

maturity (like Europe, Canada and the United States); and around 5% for emerging markets,

such as Latin America and Asia; and lowest expected growth is in intra-Caribbean countries,

at around 1.3%. The map below shows the forecast for different regions.

Figure 5: Airbus traffic forecast - Average annual growth rates 2013-2032 between Caribbean

(CAGR %)

Source: ALG, Airbus, 2013.

35

5. Policy and Regulation

There are further policies that could impact the air transport sector and therefore the

economy as a whole. These policies are, mainly, a civil aviation law that defines the

institutions, norms and regulations for the sector and the level of liberalization achieved, the

air services agreements with foreign nations, airport investments, pilot and technical training,

policies to promote activities that could benefit aviation, such as international trade and

tourism and measures to mitigate the impact of aviation on the environment. This section will

describe the effective policies the Dominican Republic has implemented that fostered

improvements in air transport.

5.1. National Framework for the Air Transport Sector

The Dominican Republic chose to make aviation a priority sector in their national

development, planning and policies. The State promulgated Law No. 491-06 in December

2006, modernizing the legislation to cope with the new standards in the sector. This initial law

was followed by two amendments, Law 67-13 and Law 29-18. JAC also released Resolution

180 (2010) and updated the requirement manual (Version 6.0, first version from 2010),

signaling further liberalization of the air transport market. The major changes reflected in

these measures are summarized below.

1. A set of strong institutions to define the air transport policies and to carry the

technical and economic regulations of the civil aviation, air traffic control,

investigation of accidents and sector's oversight:

According to Law 505-69, two institutions share the responsibilities for civil aviation in

the Dominican Republic: the Civil Aviation Board (Junta Aeronautica Civil - JAC, in Spanish)

and the General Department of Civil Aviation (Dirección General de Aviación Civil - DGAC,

in Spanish). While the Civil Aviation Board

6

was in charge of defining aviation policies and

authorizing the air transport services (frequencies, routes through permits), the Department

6

The Civil Aviation Board was a committee formed by members of the General Department of Civil Aviation, the

Dominican Armed Forces, General Director of Tourism, two aviation specialists and an attorney. The main

activities of this committee were to: (i) define the civil aviation policies; (ii) define the general plan for airports and

aerodromes and air navigation; (iii) submit the budget for construction, maintenance and rehabilitation of airports,

aerodromes and air navigation; (iv) advise the State about taxes and duties for airports, aerodromes and air

navigation; (v) define the aviation services; (vi) study the treaties and international agreements; (vii) approve or

deny agreements and contracts signed between national firms, or between national firms and foreign firms; (viii)

propose norms, regulations and procedures to the Executive; (ix) promote the aviation for tourism, trade,

agriculture.

36

of Civil Aviation was in charge of the technical and economic regulation, of air traffic control,

of airplanes registry, of investigating accidents and of airport construction, management and

oversight.

7

They also shared some responsibilities regarding the construction, maintenance

and rehabilitation of airports and in defining technical regulations.

The new laws aimed to address gaps in the institutional framework. First, the new

laws were more explicit about the responsibilities of JAC and the Dominican Institute of Civil

Aviation (the former DGAC), to avoid any overlap or conflict of interests between the two

entities. The new JAC has the responsibility of defining the general policy for civil aviation

and regulating the economic aspects for the air transport.

Second, it strengthens JAC by providing the commission with technical staff and an

annual budget to carry out their responsibilities. JAC also expanded its activities, for

example, negotiating and signing air service agreements with other countries, defining and

modifying the rules of the Committee for Investigation of Aviation Accidents and

representing the Dominican Republic in international conferences and meetings about

aviation. The organization is under the authority of the President.

Third, Law No. 491-06 grants autonomy to the Dominican Institute of Civil Aviation

(Instituto Dominicano de Aviação Civil - IDAC, in Spanish), which was previously under the

control of the President. This status means that the Institute has its own budget, technical

staff and the power to organize their own approach to oversee and control the national civil

aviation. This means the Institute and issue regulations and take decisions according to the

functions defined by the law.

Fourth, legislators created the National Air Transport Facilitation Committee (Comité

Nacional de Facilitación - CNF, in Spanish)

8

, which is in charge of procedures and

coordination for the clearance of aircrafts, people and goods through the security processes

required at international airports, and the Facilitation Committee for each international

airport. The CNF is under the authority of JAC, which is in charge of defining the

composition, functions and activities. These committees are a forum for air transport

facilitation issues to be raised and to explore new means of addressing or resolving them.

Furthermore, this structure promotes sharing of information and best practices in relation to

air transport facilitation issues and provides a platform for informing stakeholders of relevant

developments in recommended international regulations from different international

organizations, such as the ICAO.

7

The General Department of Civil Aviation was created under the Executive branch as a technical organization

with the following activities: (i) implement the decisions and resolutions by the Executive and Junta; (ii)

enforcement of aviation laws and norms of air navigation; (iii) promote the civil aviation activities; (iv) control of the

air traffic and security of air navigation; (v) propose, with the Civil Aviation Committee, the regulation needed for

the implementation of OACI recommendations; (vi) National Licensing of airplanes; (vii) requirements for titles and

licenses; (viii) administrative sanctions; (ix) investigating aviation accidents; (x) oversees the construction and

management of airports; (xi) organize and manage the air traffic in the State; (xii) meteorological services.

8

The Decree 746-08 established the organigram, functions and regular meetings.

37

In 2009, Decree 500-09 created the Facilitation Division, with the primary function of

inspecting airports. The division schedules five inspections for each airport that handles

more than 500,000 passengers and 3 for those who process less than 500,000. The main

results of the decree are: (i) the development of the National Facilitation Program (PNFTA in

Spanish), in lines with SARPs; (ii) the implementation of Norms for Air Transport Facilitation

(RFTA, in Spanish), to be approved by the CNF; (iii) and the development of a program on

accessibility for disabled people accessing airports. Regarding the last initiative, the

Division delivered an assessment report about the conditions of three international airports

for disabled people’s mobility and organized seminars about the topic in 2018. As a result,

the three international airports adapted their terminals to ease the accessibility of disabled

people. Currently, the Institute for Technical Training (INFOTEP, in Spanish) is giving a

course about sign language to JAC professionals and CNF representatives.

Fifth, the state created the Commission on Aviation Accidents Investigation, an

autonomous committee to investigate aircraft incidents and accidents on Dominican soil or

Dominican aircraft accidents on foreign soil. According to the previous law, the DGAC was

in charge of investigating aircraft accidents, which can bring about potential conflicts of

interest. For example, if accidents causes were related to the air navigation system, the

DGAC would investigate problems in the system they managed, which is a conflict of

interest. An external and neutral body is preferable and will make more accurate non-

blaming assessments and recommendations.

In short, Law 491-06 provides autonomy, independent technical staff and financial

resources to the aviation agencies in the Dominican Republic to carry out the activities of

the aviation sector with greater efficiency. Moreover, the new law created a mechanism of

division of labor along with checks and balances between the different aviation agencies in

order to avoid redundancies or conflicts of interest.

2. The incorporation of the Chicago Convention agreement and its annexes under the

national framework:

Dominican legislators incorporated the rules and procedures on International Civil

Aviation and its annexes under the national law. Law 491-06, and the amendments, granted

primacy to the best practices stated at the Chicago Convention as follows:

(a) Air traffic control: IDAC must offer and oversee the services of air traffic control

according to ICAO standards (Art. 6, g);

38

(b) Operational security: IDAC must adopt any measures to guarantee the

operational security for civil aviation, following the norms, methods and recommended

practices in the annexes of the Chicago Convention (Art. 26, d; Art. 112, a);

(c) Air Transport of cargo, luggage and dangerous goods: Any individual has to

accept or offer transport for any cargo or luggage according to the dispositions in the

annexes of the Chicago Convention and to the technical instructions for safe air

transport of dangerous goods issued by ICAO (Art.140);

(d) Airports: IDAC must adopt the necessary measures to keep the airports in an

optimum level of service, according to ICAO standards and IDAC regulations (Art. 157

and 158). The law requires mandatory airport certification to operate an airport, which

includes security and quality requirements for efficient airport service.

(e) Pilots and cabin crew: Law 29-18 grants the IDAC Director General the

responsibility to limit, through decree, the flight of pilots and cabin crew, following

domestic and international best practices.

3. More flexibility for foreign operators and relaxation of ownership requirements for

national operators.

The laws reforms also increased the participation of foreign operators in the

Dominican air sector. First, Law 491-06 allows a faster process for signing air service

agreements with other countries by granting autonomy to JAC in negotiating ASAs. The

majority of air services agreements/memorandum of understanding between the Dominican

Republic and other countries were signed after 2006, and many have been updated since

then.

Second, the new laws allow aviation authorities to grant air service permits to foreign

air carriers, even if there is no air service agreement signed by the State where the air carrier

is based. For this privilege, the Dominican Republic should ask the foreign State for

reciprocity for Dominican airlines. Third, the law extends the period that an authorization is

required for the operation of private foreign airplanes while on Dominican soil from 30 days to

90 days.

Four, JAC Resolution 108-10, currently under review, has established an open sky

policy that aims to lower restrictions on frequency, type of airplane, number of seats and

cargo volume, letting the market determine these factors. JAC also grants 6th freedom rights

for passengers, cargo and combined, and 7th freedom rights for all-cargo. Moreover, JAC

intends to let the demand and supply determine the airfare, to expand the traffic rights, to

allow multiple operators for the same route and flights through shared code agreements, and

to foster more charter and non-regular flights as a way to contribute to the growth of tourism

39

and the national economy.

Five, Law 67-13, an amendment of Law 491-06, relaxed ownership requirements for

national operators, by considering allowing companies with primarily foreign capital (up to

100%) to qualify as national carriers provided that the investment is from an internationally

known airline. Last, the JAC Requirement Manual, the regulatory framework for the Civil

Aviation Board, introduces and simplifies the requirements for the issuance of operating

permits for foreign operators and includes a regulatory framework for charters, approval of

shared code agreements between air operators and special permits.

9

Six, the Dec. 375-10

exempted the airport tax for transit passengers who are boarding cruises.

5.2. Air Services Agreement (ASAs) and Share Code Agreements

Until 2007, the Dominican Republic had signed bilateral agreements

10

with 19

countries, most of them traditional in nature (limited frequencies and routes). However, Law

491-06 has impacted the liberalization of the air services in the State. By giving JAC the

mandate to sign ASAs on behalf of the State and a technical staff to carry out the activities,

the new law boosted the number of agreements towards more liberal agreements signed

between the Dominican Republic and other countries, reaching agreements with a total of 66

countries.

9

The process for special permits takes only 10 days to conclude.

10

This includes Memorandum of Understanding, Understanding Agreement, Consultation Agreement

and the Air Services Agreements.

40

Chart 22: Number of Bilateral Agreements that the Dominican Republic has with other

countries in a specific year, 2004-2018

Source: JAC, 2018

The chart above shows that the Dominican Republic has liberalized its market to

foreign carriers by prioritizing open skies and more flexible agreements. It is worth noting that

the open sky agreements went from two (2) in 2007 to 29 in 2018, while agreements under a

flexible modality went from 7 to 25 during the same time span. Agreements under a

traditional modality became stable over the years. From the total of 66 agreements: the

majority includes 5th freedom for passenger, 19 includes 6

th

freedom for passengers and

cargo flights combined and 23 includes 7

th

freedom for cargo.

Table 2: Bilateral Agreements between Dominican Republic and foreign countries, 2018

Approach for the Agreement

Countries

Traditional (limited routes and

frequencies)

Argentina (2006); Belgium (1998); Cuba (1987/2005

1

); El

Salvador (1998); Israel (2017); México (1994); Portugal (2018);

Switzerland (2000); South Africa (2017); Trinidad and Tobago

(1992); Germany (1992/2018)

6

;

Flexible (some flexibilities, such as

tariff defined by the market,

capacity or frequencies)

Austria (1999/2007); Bahamas (2018); Canada (2008);

Colombia (2008/2011); Spain (2010/2012)

2

; Qatar (2012/2017);

Russia (2009); France (1969)

4

; Guatemala (1998); Haiti (2017);

Hungary (2003); India (2011); Italy (1971); Jamaica (2018);

Norway (2016); Denmark (2016); United Kingdom (1951/2006)

5

;

41

Czech Republic (2016); Singapore (2016); Venezuela (1970);

Bolivia (2018); Morocco (2018); Bahamas (2018), Jamaica

(2018); Kenya (2018); Poland (2018); Rwanda (2018).

Open Skies

Antigua and Barbuda (2014); Aruba (2014); Brazil (2018); Chile

(2011); Costa Rica (1998); Dubai (2007); Ecuador (2014);

United Arab Emirates (2014); United States (1949)

3

; Finland

(2016); Luxembourg (2015); Guyana (2016); Iceland (2009);

Jordan (2009/2017); Kuwait (2016); Nicaragua (2016); New

Zealand (2016); Panamá (2008); Paraguay (2010); Sweden

(2106); Curacao (2015); Saint Marteen (2013); Netherlands

(2010); Serbia (2015); Peru (2009); Sri Lanka (2017); Turkey

(2014); Uruguay (2018); China (2018).

1

The year on the left is when the State signed the MoU and, on the right, it is the year the ASA was signed.

2

Spain and the Dominican Republic signed an ASA in 1968 under the traditional approach.

3

The United States and the Dominican Republics signed an ASA in 1986 and 1999, but the Congress did not ratify these. Since

2010, they have been negotiating an open skies agreement.

4

France and the Dominican Republic signed an ASA in 1969, under the traditional approach. In 2011 and 2013, they updated

the ASA through an MoU, under a more flexible framework.

5

The United Kingdom and the Dominican Republic signed an ASA in 1951, under the traditional approach. In 2006, they

updated the ASA through an MoU, under a more flexible framework.

6

The ASA is traditional for tariffs but flexible regarding capacity.

The Dominican Republic is also a signatory state of the Air Transport Agreement of

the Association of Caribbean States, which grants rights of 5th freedom for passenger and

cargo flights combined to all member states; and of the Multilateral Agreement for Open

Skies between Member States of the Latin American Civil Association, which grants 6

th

freedom for passenger and cargo flights combined and 7

th

for cargo.

JAC has also accepted more code share agreements following the reforms, as a way

to bring more routes to the State. Currently, there are 15 active code share agreements,

which provide 25 routes from Panamá, Spain, the United States, Guadeloupe, Guyana, and

the United Kingdom, involving 15 airlines. In fact, Law No 491-06 not only defined this role

for JAC, but also dedicated articles 256-259 to this matter.

5.3. Aviation and Environment

Environmental protection is one of the priorities of IDAC. Since 2012, the organization

has participated in the National Council for Climate Change and the Clean Development

Mechanism. In 2013, IDAC prepared the first action plan to reduce CO

2

emissions from

national aviation and participated to the World Conference on Climate Change in Poland.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the European Union (UE)

signed an agreement in 2013 to implement a capacity building program for CO

2

mitigation in

42

international aviation. The Dominican Republic was one of 14 states who were selected to

participative on this initiative, serving as the ICAO office for the Caribbean States. The

project is the first phase of the Carbon Offsetting Scheme for International Aviation

(CORSIA), an ICAO program joined by the Dominican Republic.

The project has the following objectives: (i) to improve the capacity of the National

Civil Aviation authorities to develop an Action Plan on CO

2

emissions reduction in

accordance with ICAO recommendations; (ii) to design an efficient CO

2

emissions monitoring

system for international aviation developed in each selected Member State; (iii) to identify,

evaluate and partiality implement priority mitigation measures. In 2014, ICAO, UE and IDAC

organized the Kick-Off Seminar to create a plan to achieve the objectives of the project. The

2015 Action Plan defined the expectations in terms of CO

2

emissions in the DR aviation

sector for 2035 compared to a non-action scenario.

Chart 23: Baseline and Forecast for CO

2

emissions derived from aviation in the Dominican

Republic

Source: IDAC, 2018.

Between 2012-2018, Dominican stakeholders invested around USD 13 million in

measures to mitigate CO

2

emissions, including solar power plants, equipment to improve

energy efficiency in the airports, LED lights, more efficient refrigeration systems and engine

wash procedures, implementation of Preconditioned Air (PCA) units and electronic Ground

Power Units (GPU) to reduce the use of auxiliary power units (APU) in seven positions at the

Punta Cana Airport, new Performance Based Navigation (PBN) flight paths and continuous

descent and continuous climb operations, and the partial implementation of the Air Traffic

Flow Management (ATFM) concept in the main building of Air Navigation Services Norge

43

Botello. ICAO-UE measured 16.800 CO

2

fewer tons of emissions from international flights

and airports compared to the 2018 baseline (without project scenario).

The table below summarizes the main activities undertaken as a part of the

environment program between 2015-2018.

Table 3. Evolution of environmental activities for the aviation sector in the Dominican Republic

Year

Activity

2015

IDAC installed the Aviation Environmental System (AES): the Monitoring,

Reporting and Verification (MRV) tool. The AES is composed of a core database

and an internal engine for data validation and verification (to treat imported data),

as well as a component for data aggregation and analysis (to generate exported

data).

Release of the Action Plan to Reduce Emissions from the aviation sector

1

.

2016

The Dominican Republic released the first official report of CO

2

emissions in

Aviation generated by the AES.

Agreement between IDAC and the National Committee of Energy to facilitate the

implementation of renewable energy. The partnership will include a feasibility

study for the production of biofuel for the industry.

Agreement between IDAC and the Ministry of Environment to foster capacity

building in both organizations and align activities and goals.

Punta Cana Declaration, in which the National Council for Climate Change and

Clean Development Mechanism, the National Committee of Energy, the IDAC,

the JAC, the Airport Department and the Ministry of Environment agreed on a

road map to foster the use and local production of biofuel for aviation.

2017