Appendix 1

Digital labour platforms: Estimates of workers,

investments and revenues

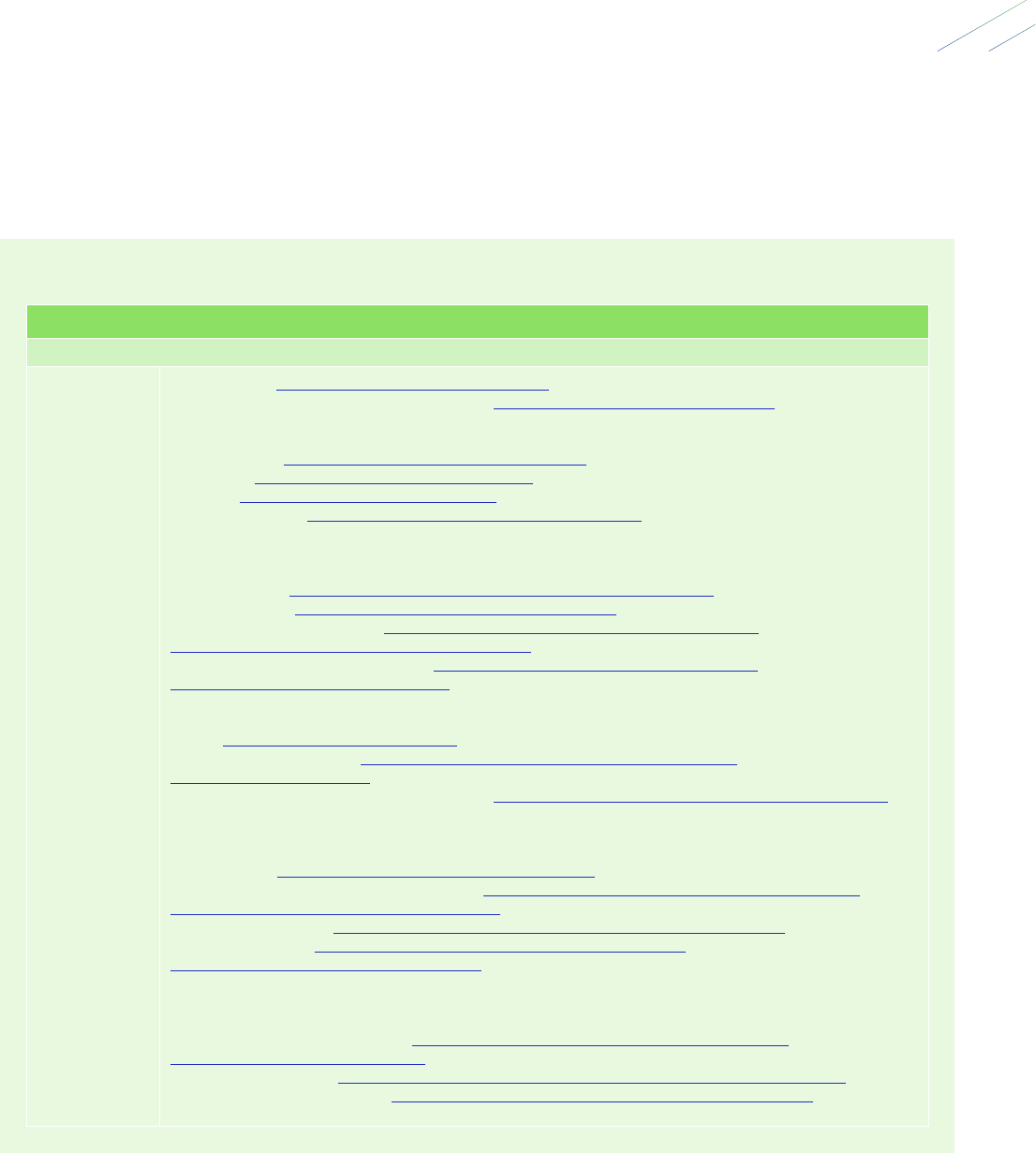

Table A1.1 List of country codes

Country

ISO

Alpha 3

Albania ALB

Algeria DZA

Argentina ARG

Armenia ARM

Australia AUS

Bangladesh BGD

Belarus BLR

Benin BEN

Bolivia, Plurinational

State of

BOL

Bosnia and Herzegovina BIH

Brazil BRA

Bulgaria BGR

Cameroon CMR

Canada CAN

Chile CHL

China CHN

Colombia COL

Costa Rica CRI

Croatia HRV

Cyprus CYP

Denmark DNK

Dominican Republic DOM

Ecuador ECU

Egypt EGY

El Salvador SLV

Ethiopia ETH

Finland FIN

Country

ISO

Alpha 3

France FRA

Georgia GEO

Germany DEU

Ghana GHA

Greece GRC

India IND

Indonesia IDN

Ireland IRL

Israel ISR

Italy ITA

Jamaica JAM

Japan JPN

Kazakhstan KAZ

Kenya KEN

Madagascar MDG

Malaysia MYS

Mauritius MUS

Mexico MEX

Morocco MAR

Nepal NPL

Netherlands NLD

New Zealand NZL

Nicaragua NIC

Nigeria NGA

North Macedonia MKD

Norway NOR

Pakistan PAK

Country

ISO

Alpha 3

Peru PER

Philippines PHL

Poland POL

Portugal PRT

Republic of Moldova MDA

Romania ROU

Russian Federation RUS

Saint Lucia LCA

Senegal SEN

Serbia SRB

Singapore SGP

Slovakia SVK

South Africa ZAF

Spain ESP

Sri Lanka LKA

Sweden SWE

Thailand THA

Tunisia TUN

Turkey TUR

Uganda UGA

Ukraine UKR

United Arab Emirates ARE

United Kingdom GBR

United States USA

Uruguay URY

Venezuela, Bolivarian

Republic of

VEN

Viet Nam VNM

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

2

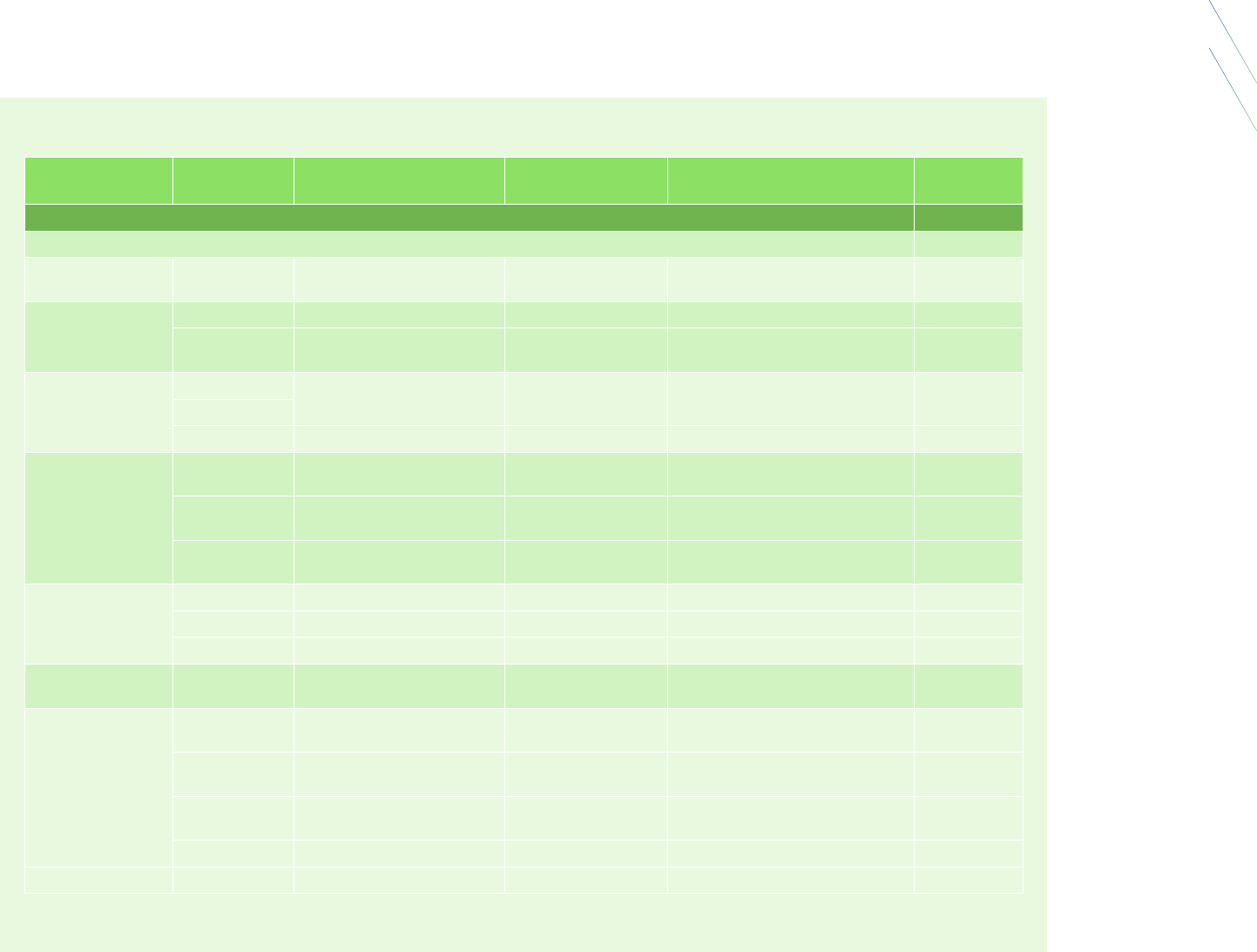

Table A1.2 Estimates of workers performing tasks on digital platforms

Reference Estimate Countries and years Time period/proportion of income Denition

Urzì Brancati,

Pesole and

Fernández Macías

(2020)

9.5–11% of adult population (aged

between 16 and 74 years)

16 EU Member

States,* 2018

Ever gained income from providing services via online

platforms.

Providing labour services via online platforms; payment

is conducted digitally via the platform, and tasks are

performed either online web-based or on-location.

1.9–2.4% of adult population

Provided labour services via platforms but less than once

a month over the last year.

3.1% of adult population

At least monthly, but for less than 10 hours a week and

earned less than 25% of their income via platforms.

4.1% of adult population

At least monthly, for between 10 and 19 hours or earned

between 25% and 50% of their income via platforms.

1.4% of adult population

At least monthly, and worked on platforms at least 20

hours a week or earned at least 50% of their income via

platforms.

Pesole et al. (2018)

9.7% on average

6–12% of adult population

14 EU Member States,

2017

Provided labour services at any time in the past.

Providing services via online platforms (location-based

and web-based).

8% on average

4–10% of adult population

Provided services regularly at least once a month in the

past year.

Alsos et al. (2017) 1% of working-age population Norway, 2016–17 Earned money through labour platforms in the past year.

CIPD (2017) 4% of working adults (18–70 years)

United Kingdom,

2016

Engaged in paid platform work at least once in the

previous 12 months.

Platform work includes performing tasks online, providing

transport or physically delivering food or other goods.

Huws et al. (2017)

9–12% in Germany, Netherlands,

Sweden, United Kingdom

18–22% in Austria, Italy, Switzerland

Austria, Germany,

Italy, Netherlands,

Sweden, Switzerland,

United Kingdom,

2016–17

Performed crowdwork at any time in the past.

Crowdwork is paid work via an online platform, such as

freelance platforms or outside one’s home on location-

based platforms.

6–8% in Germany, Netherlands,

Sweden, United Kingdom

13–15% in Austria, Italy, Switzerland

Performed crowdwork at least monthly.

5–6% in Germany, Netherlands,

Sweden, United Kingdom

9–12% in Austria, Italy, Switzerland

Performed crowdwork at least weekly.

Farrell, Greig and

Hamoudi (2018)

1.6% on all platforms

1.1% on labour platforms, 0.2% on

capital platforms, 0.4% selling (28

million US bank accounts)

United States, 2016

Earned income from platform work over the past month.

Labour platforms are those on which participants perform

discrete tasks, and capital platforms are those whose

participants sell goods or rent assets.

4.5% on all platforms Earned income from all platform work over the past year.

Appendix 1. Digital labour platforms: Estimates of workers, investments and revenues

3

Reference Estimate Countries and years Time period/proportion of income Denition

Burson-Marsteller,

Aspen Institute

and Time (2016)

42% of adult population

United States, 2015

Have purchased or used one of the services.

Services in the on-demand economy include: ride-sharing,

accommodation sharing, task services, short-term car

rental, or food or goods delivery.

22% of adult population Have oered at least one of the services in the past.

7% of adult population

Earn in a typical month at least 40% through on-demand

economy.

Katz and Krueger

(2016)

0.5% of labour force United States, 2015 Reference period – one week. Working through an online intermediary.

Surveys conducted by national statistical oces

Switzerland, FSO

(2020)

0.4% of the population

1.6% of the population

Switzerland, 2019 In the past 12 months.

Carried out work via internet-mediated platforms.

Provided internet-mediated platform services.

United States, BLS

(2018)

1% of total employment United States, 2017 In the last week.

Electronically mediated workers, doing short jobs or tasks

through websites or mobile apps that both connect them

with customers and arrange payment for the tasks.

Ilsøe and Madsen

(2017)

2.4% of working-age population

Denmark, 2017

In the past year.

Earned money via digital platforms, both labour and

capital platforms.

1% of working-age population In the past year.

Earned money via a labour platform such as Upwork,

Happy Helper.

1.5% of working-age population In the past year.

Earned money via a capital platform such as Airbnb,

GoMore.

Sweden, SOU

(2017)

4.5% of working-age population

Sweden, 2016

In the past year. Tried to get an assignment via a digital platform.

2.5% of working-age population In the past year. Performed work via a digital platform.

Canada, Statcan

(2017)

9.5% of adult population

(≥ 18 years) (7% ride services;

4.2% accommodation)

Canada, 2015–16

In the past 12 months.

Used either peer-to-peer ride services or private

accommodation services.

0.3% of adult population (≥ 18 years) In the past 12 months. Oered peer-to-peer ride services.

0.2% of adult population (≥ 18 years) In the past 12 months. Oered private accommodation services.

Statistics Finland

(2018)

7% of adult population Finland, 2017 In the past 12 months.

Worked or earned income from the following platforms:

Airbnb, Uber, Tori./Huuto.net, Solved, and others.

* These 16 EU Member States are Czechia, Croatia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom.

Source: ILO compilation.

Table A1.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

4

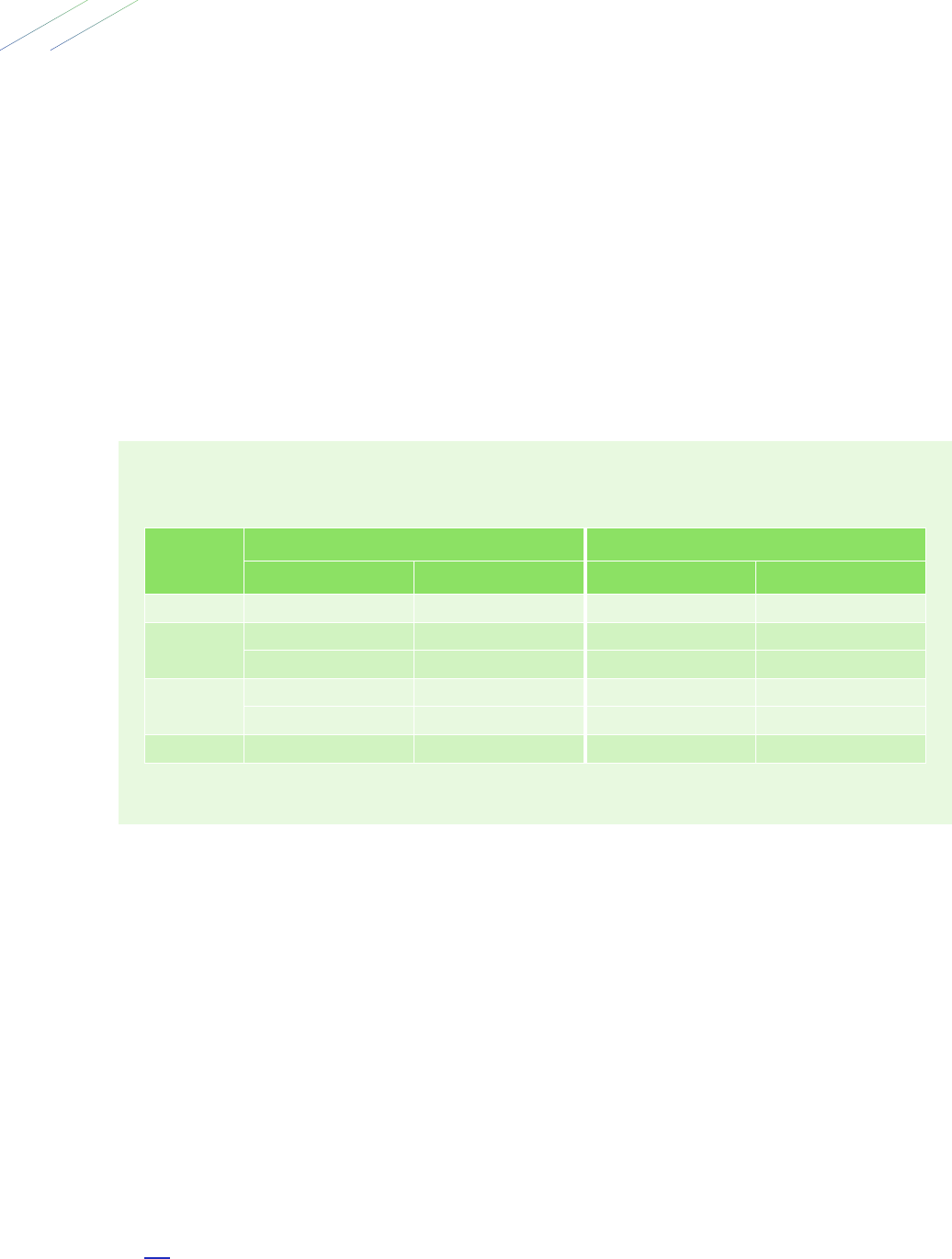

Table A1.3 Total funding from venture capital and other

investors, selected categories of digital labour platforms,

by region and type of platform, 1999–2020

Funding

(US$ million)

Number

of platforms

Number

of countries

Delivery 37 495 164 47

Africa 13 5 4

Arab States 48 6 5

Central and Western Asia 51 6 4

East Asia 8 915 16 3

Eastern Europe 110 10 3

Latin America and the Caribbean 3 019 15 9

North America 11 116 44 2

South Asia 4 19 9 21 2

South-East Asia and the Pacic 222 8 3

Western Europe 9 803 33 12

Taxi 62 784 61 30

Africa 45 8 6

Arab States 772 1 1

Central and Western Asia 929 2 2

East Asia 21 581 4 2

Eastern Europe 1 001 2 2

Latin America and the Caribbean 337 6 3

North America 33 032 19 1

South Asia 3 850 5 4

South-East Asia and the Pacic 26 4 2

Western Europe 1 211 10 7

Online web-based 2 69 0 142 31

Arab States 0.3 1 1

Central and Western Asia 113 4 2

East Asia 579 11 3

Eastern Europe 12 5 3

Latin America and the Caribbean 2 4 3

North America 1 601 66 2

South Asia 7 6 2

South-East Asia and the Pacic 77 9 5

Western Europe 299 36 10

Hybrid 16 999 5 4

Africa 908 1 1

South-East Asia and the Pacic 15 10 0 2 2

East Asia 991 2 1

Source: Crunchbase database.

Appendix 1. Digital labour platforms: Estimates of workers, investments and revenues

5

Table A1.4 Estimated annual revenue of digital labour

platforms, by region and type of platform, 2019–20

Revenue

(US$ million)

Number

of platforms

Number

of countries

Delivery 25 063 191 36

Africa 10 3 4

Arab States 113 7 3

Central and Western Asia 231 1 1

East Asia 9 107 101 4

Eastern Europe 63 7 5

Latin America and the Caribbean 934 6 4

North America 9 10 4 34 1

South Asia 690 10 1

South-East Asia and the Pacic 90 6 5

Western Europe 4 772 16 8

Transportation 17 343 31 18

Africa 7 2 2

Arab States 119 1 1

Central and Western Asia 1 000 1 1

East Asia 401 1 1

Eastern Europe 501 1 1

Latin America and the Caribbean 17 2 1

North America 14 521 9 1

South Asia 460 4 3

South-East Asia and the Pacic 17 3 2

Western Europe 300 7 5

Online web-based 2 509 107 22

Africa 2 1 1

Central and Western Asia 107 1 1

East Asia 127 6 3

Eastern Europe 24 3 2

Latin America and the Caribbean 1 1 1

North America 1 572 61 2

South Asia 26 7 1

South-East Asia and the Pacic 494 7 4

Western Europe 155 20 7

Hybrid 6 273 5 4

Africa 180 1 1

South-East Asia and the Pacic 3 60 0 2 2

East Asia 2 493 2 1

Source: Owler database, annual reports and lings by platform companies to the Securities

and Exchange Commission of the United States.

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

6

Table A1.5 Mergers and acquisitions in delivery platforms

Name of platform

Merger/

acquisition

Name of platform/company

(merged with/acquired by)

Date

of merger/

acquisition

Appetito24 Acquisition PedidosYa (acquired by Delivery Hero) 14.08.2017

Baedaltong Acquisition Delivery Hero 09.12. 2014

BGMENU.com Acquisition Takeaway.com (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 23.02.2018

Canary Flash Acquisition Just Eat (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 01.09.2019

Carriage Acquisition Delivery Hero 29.05.2017

Caviar Acquisition DoorDash 01.08.2019

Chef Shuttle Acquisition Bitesquad 23.06.2017

CitySprint Acquisition LDC 19.02.2016

Dáme Jídlo Acquisition Delivery Hero 09.01.2015

Daojia Acquisition Yum! China 17.05.2017

Delicious Deliveries Acquisition Bitesquad 10.10.2017

Deliveras Acquisition Delivery Hero 12.02.2018

Delivery.com Acquisition Uber 11.10.2019

Delyver Acquisition Big Basket 12.06.2015

Domicilios.com Acquisition iFood 08.04.2020

Doorstep Delivery Acquisition Bitesquad 28.08.2017

Eat24 Acquisition Grubhub 03.08.2017

Eats Media Acquisition delivery.com 26.08.2009

Eda.ua Acquisition Menu Group (UK) Limited 05.08.2019

Favor Acquisition HE Butt Grocery 15.02.2018

Feedr Acquisition Compass Group PLC 26.05.2020

Foodarena.ch Acquisition Takeaway.com (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 22.06.2018

Foody Acquisition Delivery Hero 20.09.2017

Foodfox Acquisition Yandex 28.11.2017

Foodie Call Acquisition Bitesquad 10.10.2017

FoodNinjas Acquisition Velonto 04.2020

Foodonclick.com Acquisition Delivery Hero 05.2015

Foodora Acquisition Delivery Hero 09.2015

Foodpanda Acquisition Delivery Hero 10.12.2016

Foodpanda India Acquisition Ola 19.12.2017

FoodTime Acquisition Fave 24.05.2019

Appendix 1. Digital labour platforms: Estimates of workers, investments and revenues

7

Name of platform

Merger/

acquisition

Name of platform/company

(merged with/acquired by)

Date

of merger/

acquisition

Freshgora

Minority stake

investment

Meal Temple Group 2019

Gainesville2Go Acquisition Bitesquad 01.10.2017

HipMenu Acquisition Delivery Hero 08.2018

Honest Food Acquisition Delivery Hero 20.12.2019

Hungerstation.com Acquisition Foodpanda 09.08.2016

Lieferando Acquisition Takeaway.com (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 10.04.2014

Menulog Acquisition Just Eat (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 08.05.2015

Mjam Acquisition Delivery Hero 2012

MyDelivery Acquisition Meal Temple Group 26.02.2019

NetPincér hu Acquisition Foodpanda, then by Delivery Hero

12.2014

and 12.2016

respectively

PedidosYa Acquisition Delivery Hero 26.06.2014

Pyszne.pl Acquisition Lieferando, then by Just Eat Takeaway.com

23.03.2012

and

10.04.2014

respectively

Rickshaw Acquisition DoorDash 14.09.2017

SberMarket Acquisition Sberbank 30.11.2020

Seamless Acquisition Grubhub 01.05.2013

SkipTheDishes Acquisition Just Eat (now Just Eat Takeaway.com) 15.12.2016

Stuart Acquisition Geopost 07.05.2017

Takeaway.com and Just Eat Merger Just Eat Takeaway.com 23.04.2020

Talabat Acquisition Internet Rocked, then by Delivery Hero

02.2015

and 12.2016

respectively

Tapingo Acquisition Grubhub 25.09.2018

Uber Eats (India) Acquisition Zomato 21.01.2020

Waitr Acquisition Landcadia Holdings 16.05.2018

Woowa Bros Acquisition Delivery Hero 12.2020

Yemeksepeti Acquisition Delivery Hero 05.05.2015

YoGiYo Acquisition Delivery Hero 2014

Zakazaka Acquisition Mail.Ru Group 02.05.2017

Source: Crunchbase database, annual reports and platform websites.

Table A1.5 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

8

Table A1.6 Mergers and acquisitions in taxi platforms

Name of platform

Merger/

acquisition

Name of platform/company

(merged with/acquired by)

Date

of merger/

acquisition

99 Acquisition DiDi 03.01.2018

Beat Acquisition Intelligent Apps 16.02.2017

Careem Acquisition Uber 26.03.2019

Citybird Acquisition Felix 12.06.2018

Curb Acquisition Verifone 13.10.2015

Easy Taxi Acquisition Cabify 01.01.2017

Fasten Acquisition Vezet Group, then by MLU BV

02.03.2018

and 15.07. 2019

respectively

Flinc Acquisition Diamler 28.09.2017

FREE NOW Acquisition Intelligent Apps 26.07.2016

Savaree Acquisition Careem, then by Uber

30.03.2016

and 26.03.2019

respectively

Vezet Group Acquisition MLU BV 15.07.2019

Yandex.Taxi and Uber (Russia, CIS) Merger MLU BV 02.2018

Source: Crunchbase database, annual reports and platform websites.

Appendix 1. Digital labour platforms: Estimates of workers, investments and revenues

9

Table A1.7 Mergers and acquisitions in online web-based platforms

Name of platform

Merger/

acquisition

Name of platform/company

(merged with/acquired by)

Date

of merger/

acquisition

99designs Acquisition VistaPrint 05.10.2020

Applause Acquisition Vista Equity Partners 23.08.2017

AudioKite Acquisition ReverbNation 04.11.2016

Brandstack Acquisition DesignCrowd 20.12.2011

ClearVoice Acquisition Fiverr 13.02.2019

Codechef Acquisition Unacademy 18.06.2020

DesignCrowd

Acquisition

and merger

DesignBay

(since renamed DesignCrowd)

23.11.2009

Freelancer Technology Acquisition Music Freelancer.net 02.01.2019

Gengo Acquisition Lionbridge 16.01.2019

Guru Acquisition Emoonlighter 01.07. 2003

Indiez Acquisition GoScale 26.02.2020

Iwriter Acquisition Templafy 07.05.2019

Kaggle Acquisition Alphabet (includes Google) 07- 03.2017

Liveops Acquisition Marlin Equity Partners 01.12.2015

Mila Acquisition Swisscom 02.01.2013

MOFILM Acquisition You & Mr Jones 11.06.2015

Streetbee Acquisition BeeMyEye 16.01.2019

Test IO Acquisition EPAN Systems 21.05.2019

Topcoder Acquisition Appirio, then by Wipro Technologies

17.09. 2013

and

20.10.2016

respectively

Twago Acquisition Randstad 14.06.2016

VerbalizeIt Acquisition Smartling 19.05.2016

WeGoLook Acquisition Crawford & Company 06.12.2016

Xtra Global Acquisition Rozetta Corp 09.08.2016

Zooppa Acquisition TLNT Holdings SA 07.2019

Source: Crunchbase database, annual reports and platform websites.

Appendix 2

ILO interviews with digital platform companies

and analysis of terms of service agreements

2A. ILO interviews with digital platform companies

To understand the functioning of digital platform companies, interviews with representatives of

both location-based platforms and online web-based platforms were conducted. With regard to

location-based platforms, interviews with representatives of taxi and delivery platforms were

conducted, in collaboration with consultants, using a semi-structured questionnaire prepared

by the ILO. The consultants approached taxi and delivery platforms in their cities of operations,

requesting them to participate on the basis of a letter provided by the ILO. The interviews

collected information on the platforms’ business proles, operations and marketing strategies,

business model, recruitment practices and future strategies. However, only a few taxi platforms

(in Chile, Ghana, India and Kenya) and one delivery platform (in Ghana) agreed to the interviews,

which were conducted in person by the consultants or using video call by the ILO.

With regard to online web-based platforms, the ILO contacted about 30 platform companies

with signicant or growing presence at the country or regional levels, requesting them to

participate in the study. The ILO conducted interviews with eight such platform companies and

with one open-source platform (Apache Software Foundation). The interviews used semi-struc-

tured questionnaire, which were quite similar to those for the taxi and delivery platforms but

platform specic. In addition, the interviews sought information related to tasks, matching

process, algorithmic management, work evaluation and the platforms’ global operations. All

these interviews were conducted using video call, and follow-up meetings were held with

some platforms.

Table A2.1 lists the platform companies whose representatives were interviewed. The inter-

views were conducted between March 2019 and March 2020, and took between approximately

30 minutes and two hours.

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

2

X

Table A2.1 Interviews conducted with digital platform companies

Platform company Person interviewed Coverage

A. Online web-based platforms

1. Clickworker CEO Berlin, Germany

2. Upwork Human Resources Manager Santa Clara, California, United States

3. Hsoub CEO London, United Kingdom

4. Worknasi CEO United Republic of Tanzania

5. Nabeesh CEO United Arab Emirates

6. Playment CEO Bengaluru, India

7. Crowd Analytix CEO Bengaluru, India

8. GoWorkABit

CEO (and member of the Sharing

Economy Association)

Estonia

9. Apache Foundation Board member (and Treasurer) Berlin, Germany

B. Location-based platforms

Taxi platforms

1. Uber Employee, operations department Accra, Ghana

2. Maramoja Employee, operations department Nairobi, Kenya

3. Uber

Employee, responsible for public policy

in East Africa

Nairobi, Kenya

4. Bolt Employee Nairobi, Kenya

5. Ola Employee, operations department New Delhi, India

6. Beat CEO Santiago, Chile

7. DiDi Director, corporate aairs Santiago, Chile

Delivery platforms

1. Okada Employee, operations department Accra, Ghana

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

3

2B. Analysis of terms of service agreements

The terms of service agreements and other related documents of 31 platforms have been analysed

for this report. Chapters 2 and 5 draw on this analysis to understand the functioning of the platform

business model. Of these, 16 are online web-based platforms (4 freelance, 3 contest-based, 5 competitive

programming and 4 microtask) and 15 are location-based platforms, of which 7 are in the taxi sector and

8 are in the delivery sector, operating in a number of countries.

The online web-based platforms were chosen because of their coverage in the global microtask, freelance

and competitive programming surveys for this report, and some additional platforms were analysed

because of their prominence. All the location-based platforms analysed for the business model were iden-

tied in the country-specic worker surveys that were conducted in Africa (Ghana, Kenya and Morocco),

Asia (China, India and Indonesia), Central and Eastern Europe (Ukraine), Latin America (Argentina, Chile

and Mexico), and the Middle East (Lebanon). The exception is Deliveroo, which was considered for ana-

lysis because of its distinct characteristics compared to other delivery platforms, in order to enable a

comparison to be made with these other platforms. In addition, with respect to Grab and Gojek, the

terms of service agreements for Singapore were also analysed, as both these platforms are based there;

some key aspects of the agreements in Singapore may dier from those in other countries where these

platforms operate. The platform websites provide information related to the agreements and other

related documents (see table A2.2). Where it was not possible to obtain the information required, the

information from the country surveys and interviews conducted for the purposes of this report were

used.

1

The analysis focuses on the following aspects:

X

Contractual relationship: The terms of service agreements of both online web-based and loca-

tion-based platforms provide information on the contractual relationship. They all use terminology

which seeks to deny any relationship of employment between themselves and the platform users (see

tables A2.2 and A2.3 for more details).

X

Types of services: The websites of both online web-based and location-based platforms provide

information on the types of services available. Though the terms of service agreements also provide

such information, this is usually very brief compared to the details posted on the main websites. For

online web-based platforms in particular, information included in the main text of this report is also

based on the interviews conducted with representatives of the platforms.

X

Revenue model: The websites of online web-based platforms provide information on the dierent

types of fees charged to the various users (clients, workers and so on). These include fees for on-

boarding, commission fees or service charges for performing the tasks, transaction/withdrawal fees,

maintenance fees and cancellation charges. Some of the platforms also have optional fees, which

include fees for clients to mark projects as urgent or to highlight them so as to attract higher-quality

submissions, and fees for workers to obtain access to more job proposals and better listings. Some

also have a subscription model, and the amounts payable for the various subscriptions along with the

dierent services and benets they provide are available on the respective platform websites.

In the case of location-based platforms, the terms of service agreements of both transportation and

delivery platforms provide information on the types of fees charged, which almost invariably include

commission fees, cancellation fees and waiting-time fees, as well as various other surcharges, such as

for airport trips and tolls or for cleaning and maintenance services. The terms and conditions of loca-

tion-based platforms also provide information on surge pricing, specifying that the prices of services

vary according to demand and supply. Nevertheless, the agreements do not include information on

the exact amount of these fees. For some platforms, such as Bolt and Cornershop in Mexico, and Grab

or GrabFood and Gojek in Singapore, more precise information on commission fees can be found on

their websites (usually in the FAQ or support sections), but where such information was not available, it

was collected from the surveys of taxi drivers and delivery workers in the various countries, and from

the interviews conducted with restaurant and grocery shop owners.

1 The text indicates when that is the case.

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

4

X

Recruitment and matching: Information on onboarding requirements and procedures was collected

from a number of sources. In some cases, privacy policies stipulate that users can access platforms

via third parties, such as social networking services, while for other platforms this information can be

deduced from the registration sections on their websites, which clearly give users the option to sign

up via third parties such as Google, Facebook or LinkedIn.

For instance, the privacy policies of both online web-based and location-based platforms provide

information on the documents needed to create an account. In the case of location-based platforms,

in particular, information on both the personal and technical requirements needed for joining as either

a driver or a courier (depending on whether the platform provides transportation or delivery services)

was collected from the registration sections on the platforms’ websites. Moreover, the support or

frequently asked question (FAQ) sections of online web-based platforms’ websites contain information

on verication and vetting procedures, which can include anything from ID verication via camera to

registration of user proles based on standards set by the platform. Information was also collected

from the country-specic surveys and the interviews conducted with companies for this report. Finally,

much of the information on the indicators used in assignment of work is based on an analysis of the

websites of 117 online labour platforms listed on Crunchbase.

X

Work processes and performance management: The websites of online web-based platforms con-

tain various sections relevant to work processes and performance management. There are sections

analysing platforms’ rating systems and the various levels assigned to workers based on such ratings,

and others referring to tools that the platforms make available to facilitate communication between the

parties and that enable them to track projects in real time (for example, in-app messaging systems, live

chat features and remote desktop apps). There are specic sections outlining the testing methods that

determine workers’ continued access to tasks and to the platforms. Information on the ratings systems

used by location-based platforms was more dicult to obtain. Their terms of service agreements are

usually silent on the matter and only a few platforms outline their rating systems on their websites.

Though most of the information concerning both online web-based and location-based platforms

was collected from their websites, the terms of service agreements were also relevant; they often

include clauses prohibiting activities such as communication between parties and payment being

made outside the platform, the use of automated methods (such as Google Translate in the case of

Appen) or the use of subcontractors. In the case of location-based platforms in particular, terms and

conditions include provisions on codes of conduct, customer service etiquette, and cancellation and

communication time frames.

Rules of platform governance

X

Account access/deactivation: Information on who can access the platforms and under what condi-

tions was mostly collected from terms of service agreements. In general, both online web-based and

location-based platforms deactivate user accounts when the users are considered to have breached

the terms of service agreements. That said, the power of platforms to deactivate accounts is often

broadly formulated. Many agreements contain clauses on platforms’ discretionary power to refuse

registration and deactivate accounts, often without the need to provide a reason or prior notice. In

the case of online web-based platforms, in particular, their websites often include sections with add-

itional information on deactivation and the reasons that might lead to it, which can include low ratings,

plagiarism or simply unoriginality of work, breach of codes of conduct (for instance, abuse of other

users), non-performance or submission of work which does not meet the platform’s or the client’s

specications or quality standards.

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

5

X

Dispute resolution: Most information on the dispute resolution processes of both online web-based

and location-based platforms was collected from the terms of service agreements, which usually con-

tain entire sections dedicated to dispute resolution in which the governing law and jurisdiction are

clearly specied. In the case of online web-based platforms, such sections tend to be lengthier, given

that dispute resolution procedures usually take the form of arbitration proceedings, the conditions

of which are dened in detail by the platforms. In addition, online web-based platforms often include

dierent dispute resolution policies depending on the issue in question, and information on these

dierent policies is usually located on their websites. For instance, Upwork has dierent dispute reso-

lution procedures for hourly and xed-price contracts. Online web-based platforms also tend to have

separate dispute resolution processes for disputes concerning intellectual property. For location-based

platforms, the governing law and jurisdiction is usually that of the country where the services are being

provided, though in some cases it is that of another country, as is the case with certain countries where

Uber, Bolt and Glovo operate.

X

Data collection and usage: Obtaining information on the data that platforms collect and how they

process it was fairly straightforward, since such information is provided through privacy policies which

are uniformly structured. These policies, for both online web-based and location-based platforms,

clearly specify the kind of data collected, how it is collected, when and from where, as well as how they

use it and when and with whom they share it. Data can be collected directly (i.e. when users provide

it) or indirectly (i.e. by technological means such as cookies). Data collected directly from users varies

across platforms and can include a user’s contact and nancial details, specic identity documents,

criminal records, vehicle registration and insurance documents, or even more sensitive information

such as race, religion and marital status (the latter observed only for Grab).

Data collected indirectly also varies, and can include anything from usage data (such as browsing and

searching history, areas within the platform visited, duration of visits and number of clicks) and device

information (such as IP address, device identier and browser type), to data on communication between

users and other data stored in the user’s device (information from address books and calendars, or

even the names of other applications installed in the device). Such automatically collected information

also includes data relating to worker performance, such as their ratings and participation statistics,

while location-based platforms may even collect driving-related data such as real-time geolocation

and acceleration or braking data (as the privacy policies for Uber and Grab specify).

Apart from describing the kinds of data they collect, platforms’ privacy policies also outline the

various ways in which they use such data. For instance, they process user data to provide, enhance

and personalize their services, to understand how users use their services, to comply with the law, and

for automated decision-making (for instance the privacy policy of Uber species that it uses data to

match workers with clients, determine prices based on demand and suspend or deactivate accounts).

Although platforms may describe in detail the kinds of data they collect and the ways in which they

process it, they do not, however, clearly link data collection to data processing; in other words, it is not

always clear how a particular kind of data, such as location data, is used. Moreover, platforms share

user data with their business partners, with other users of the platform, and with an array of third-

party service providers including payment processors, insurance and nancial partners, advertising

companies, social networking services, cloud storage providers, research and marketing providers,

and law enforcement agencies. Privacy policies provide information on data protection, usually by

asserting that they abide by certain data protection laws, such as the European Union’s General Data

Protection Regulation, or that they ensure that any party with access to the platform’s data abides by

its privacy policy.

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

6

X

Intellectual property rights (IPR): The terms of service agreements of both online web-based and

location-based platforms clearly state that any IPR rest with the platform. In the case of online web-

based platforms, however, it is not always clear in the terms and conditions which party has IPR over

the creative work produced via the platform. In most cases, IPR are transferred from the worker to the

client upon payment, though in some cases (such as Toptal) workers contractually assign any rights

in their work to the platform, which then transfers such rights to the clients upon payment. Certain

online web-based platforms also require that users sign non-disclosure agreements – as is the case

with private contests in 99designs and Designhill – while other platforms give clients the option to sign

such an agreement in return for a fee (such as Freelancer, PeoplePerHour). This information, wherever

possible, was collected from the platform websites, though often such information was not available.

X

Taxation: All the online web-based and location-based platforms under analysis specify that any prices

quoted on the platform are inclusive of taxes, and emphasize that the responsibility to determine and

pay taxes falls on the users (workers and clients). Nevertheless, there are some platforms that mention

in their terms of service that they deduct taxes from workers’ earnings. For instance, both Ola and

Zomato in India make deductions from proceeds as per the Income Tax Act, 1961. Freelancer recently

updated its “Fees and Charges” policy by adding a section on taxation, specifying that taxes will be

applied based on a user’s country of residence/registration. Similarly, Uber’s updated terms for Chile

state that Uber will transfer and collect the applicable taxes.

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

7

X

Table A2.2 Online sources of platforms’ terms of service agreements

A) Online web-based platforms

Freelance platforms

Freelancer

User agreement: https://www.freelancer.com/about/terms

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.freelancer.com/about/privacy

Revenue model

Fees and charges: https://www.freelancer.com/feesandcharges/

Membership: https://www.freelancer.com/membership/

Enterprise: https://www.freelancer.com/enterprise

Project management: https://www.freelancer.com/project-management/

Also see link under user agreement.

Ranking/ratings

Freelancer ratings: https://www.freelancer.com/support/General/freelancer-ratings

Freelancer rewards: https://www.freelancer.com/faq/topic.php?id=42

The preferred freelancer program: https://www.freelancer.com/support/freelancer/general/

the-preferred-freelancer-program?keyword=preferred

What is the preferred freelancer program?: https://www.freelancer.com/community/articles/

what-is-the-preferred-freelancer-program

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.freelancer.com/signup

Restrictions in some countries: https://www.freelancer.com/support/freelancer/General/

restrictions-in-some-countries

Know your customer and identity verication policy: https://www.freelancer.com/page.php?p=info%2Fkyc_policy

Also see links under user agreement and revenue model.

Work processes and performance management

Code of conduct: https://www.freelancer.com/info/codeofconduct

Communicating or paying outside Freelancer.com: https://www.freelancer.com/support/freelancer/General/

communicating-or-paying-outside-freelancer-com

Messaging my employers: https://www.freelancer.com/support/project/messaging-on-projects

Using the desktop app: https://www.freelancer.com/support/freelancer/project/

using-the-desktop-app?keyword=desktop%20a

Also see link under user agreement.

Rules of platform governance

Violations that lead to account closure: https://www.freelancer.com/support/freelancer/General/

violations-that-lead-to-account-closure

Reopening closed account: https://www.freelancer.com/support/Prole/can-i-reopen-my-closed-account

Milestone dispute resolution policy: https://www.freelancer.com/page.php?p=info%2Fdispute_policy

Also see links under user agreement and code of conduct.

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

8

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Freelance platforms (cont’d)

PeoplePerHour

Terms and conditions: https://www.peopleperhour.com/static/terms

For data collection and usage see the privacy and cookies statement: https://www.peopleperhour.com/static/

privacy-policy

Revenue model

Loyalty programs for premium buyers: https://www.peopleperhour.com/premium-programme

What’s the dierence between PeoplePerHour and TalentDesk.io?: https://www.peopleperhour.com/blog/

product-platform/dierence-between-peopleperhour-and-talentdesk-io/

Also see link under terms and conditions.

Ranking/ratings

Understanding CERT: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/articles/205218587-Understanding-CERT

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.peopleperhour.com/site/register

Your freelancer application: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/

articles/205217827-Your-Freelancer-Application

Freelancer application got declined: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360039120094-Freelancer-Application-got-declined?mobile_site=false

Verify your account: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360001764608-Verify-your-Account?mobile_site=false

Prole policies: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/articles/205218177-Prole-policies

PeoplePerHour academy: https://www.peopleperhour.com/academy

Also see links under terms and conditions, and revenue model.

Work processes and performance management

WorkStream policies: https://support.peopleperhour.com/hc/en-us/articles/205218197-WorkStream-Policies

Also see links under terms and conditions, and prole policies.

Rules of platform governance

See links under terms and conditions, prole policies, and WorkStream policies.

Toptal

Terms and conditions: https://www.toptal.com/tos

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.toptal.com/privacy

Revenue model

Enterprise: https://www.toptal.com/enterprise

The Toptal referral partners program: https://www.toptal.com/referral_partners

Frequently asked questions: https://www.toptal.com/faq

Recruitment and matching

See links under terms and conditions, privacy policy, and frequently asked questions.

Rules of platform governance

See links under terms and conditions, and frequently asked questions.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

9

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Freelance platforms (cont’d)

Upwork

User agreement: https://www.upwork.com/legal#useragreement

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.upwork.com/legal#privacy

Revenue model

Pricing: https://www.upwork.com/i/pricing/

Freelancer plus: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211062888-Freelancer-Plus

Enterprise: https://www.upwork.com/enterprise/

Featured jobs: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/115010712348-Featured-Jobs

Use connects: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211062898-Use-Connects; https://support.upwork.

com/hc/en-us/articles/360057604814-11-24-FREE-Connects-to-Do-More-on-Upwork-

How to bring your own talent to Upwork: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360051696934-How-to-Bring-Your-Own-Talent-to-Upwork

Fee and ACH authorization agreement: https://www.upwork.com/legal#fees

Hourly, bonus, and expense payment agreement with escrow instructions: https://www.upwork.com/

legal#escrow-hourly

Fixed-price escrow instructions: https://www.upwork.com/legal#fp

Milestones for xed-price jobs: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211068218-Milestones-for-Fixed-Price-Jobs

PayPal fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211063978-PayPal-Fees-and-Timing

Payoneer fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211064008-Payoneer-Fees-and-Timing

M-Pesa fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/115001615787-M-Pesa-Fees-and-Timing-

Wire transfer fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211063898-Wire-Transfer-Fees-and-Timing

Direct to local bank fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211060578-Direct-to-Local-Bank-Fees-and-Timing-

Direct to US bank (ACH) fees and timing: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/227022468-Direct-to-US-Bank-ACH-Fees-and-Timing

Also see link under user agreement.

Ranking/ratings

Job success score: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211068358-Job-Success-Score

Upwork’s talent badges: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360049702614

Expert-vetted talent: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360049625454-Expert-Vetted-Talent

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.upwork.com/signup/?dest=home

Eligibility to join and use Upwork: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211067778-Eligibility-to-Join-Upwork

Create a 100% complete freelancer prole: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211063188-Create-a-100-Complete-Freelancer-Prole

Application to join Upwork declined: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/214180797-Application-to-Join-Upwork-Declined

Multiple account types: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001171768-Multiple-Account-Types

ID verication badge: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360010609234-ID-Verication-Badge

Types of ID verication: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001176427-Types-of-ID-Verication

Sele ID review process: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001706047-Sele-ID-Review-Process

Also see links under user agreement, privacy policy, pricing, Freelancer plus, enterprise, featured jobs, and use connects.

Work processes and performance management

Upwork’s work diary: what it is and why use it: https://www.upwork.com/hiring/community/upworks-work-diary/

About the desktop app: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211064038-About-the-Desktop-App

Upwork for clients app: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211064028-Upwork-for-Clients-App

Upwork for freelancers app: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360015504093-Upwork-for-Freelancers-App

Use messages: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211067768-Use-Messages

Video and voice calls: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/217698348-Video-and-Voice-Messaging

Freelancer education hub: https://www.upwork.com/hiring/education/getting-started-for-freelancers/

Readiness test: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/360047551134-Upwork-Readiness-Test

Also see link under user agreement.

Rules of platform governance

Freelancer violations and account holds: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/

articles/211067618-Freelancer-Violations-and-Account-Holds

Non-disclosure agreements: https://support.upwork.com/hc/en-us/articles/211063608-Non-Disclosure-Agreements

Also see links under user agreement; hourly, bonus, and expense payment agreement with escrow instructions;

xed-price escrow instructions; and multiple account types.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

10

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Contest-based platforms

99designs

Terms of use: https://99designs.com/legal/terms-of-use

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://99designs.com/legal/privacy

Revenue model

Pricing: https://99designs.com/pricing

What is a platform fee?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/360022206031

What is a client introduction fee?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/360022018152

Can I choose how much I pay for a contest?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204760735-Can-I-choose-how-much-I-pay-for-a-contest-

What is a payout and how do I request one?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204108819-What-is-a-payout-and-how-do-I-request-one-

100% money-back guarantee? for real?!: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204108729-100-Money-back-guarantee-For-real-

Also see link under terms of use.

Ranking/ratings

What are designer levels?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/115002951643-What-are-designer-levels-

What are the benets for each designer level?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/360022097311

What is top level status?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001153443

Availability status and responsiveness score: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360000537386-Availability-Status-and-Responsiveness-Score

Recruitment and matching

How does 99designs’ application process work?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360036552311-How-does-99designs-application-process-work-

What are 99designs’ quality standards?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204862935-What-are-99designs-quality-standards-

What is identity verication?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/205460145-What-is-identity-verication-

Can I have more than one account?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204761325-Can-I-have-more-than-one-account-?mobile_site=false

Best design awards: https://99designs.com/best-design-awards/

Also see links under terms of use, privacy policy, pricing, and ranking/ratings.

Work processes and performance management

Designer code of conduct: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/204109559-Designer-Code-of-Conduct

Designer resource center: https://99designs.com/designer-resource-center

Also see links under terms of use, pricing, and what are 99designs’ quality standards?

Rules of platform governance

Non-circumvention policy: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360022405192-Non-Circumvention-Policy

What’s a non-disclosure agreement (NDA)?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/

articles/204760785-What-s-a-non-disclosure-agreement-NDA-

Who owns what and when?: https://support.99designs.com/hc/en-us/articles/204761115-Who-owns-what-and-when-

Also see links under terms of use; what are 99designs’ quality standards?; can I have more than one account?; and

designer code of conduct.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

11

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Contest-based platforms (cont’d)

Designhill

Terms and conditions: https://www.designhill.com/terms-conditions

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.designhill.com/privacy

Revenue model

Pricing guide: https://www.designhill.com/pricing/logo-design?services=contest

What is included in the enterprise package?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360013633753-What-is-included-in-the-Enterprise-package-

Here is what you get when you go for subscription upgradation: https://www.designhill.com/design-blog/

here-is-what-you-get-when-you-go-for-subscription-upgradation/

Why should you upgrade your designer membership subscription?: https://www.designhill.com/design-blog/

why-should-you-upgrade-your-designer-membership-subscription/

What is a payout and how do I request one?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115001380229-What-is-a-payout-and-how-do-I-request-one-

Can I choose how much I pay for a contest?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115001213765-Can-I-choose-how-much-I-pay-for-a-contest-

How much do 1-to-1 projects cost to customers?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115001517009-How-much-do-1-to-1-Projects-cost-to-customers-

Also see link under terms and conditions.

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.designhill.com/signup

How can I create an account?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115001187805-How-can-I-create-an-account-

Can I have multiple accounts?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115001186685-Can-I-have-multiple-accounts-

Also see links under terms and conditions; pricing guide; what is included in the enterprise package?; here is what

you get when you go for subscription upgradation; and why should you upgrade your designer membership

subscription?

Work processes and performance management

Designer code of conduct: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004513989

Free small business tools online: https://www.designhill.com/tools/

Also see links under pricing guide.

Rules of platform governance

Suspension policy: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004544629-Suspension-Policy

Concept originality policy: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/articles/115004544729-

What if someone breaches my NDA?: https://support.designhill.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360013262574-What-if-someone-breaches-my-NDA-

Also see links under terms and conditions; can I have multiple accounts?; and designer code of conduct.

Hatchwise

Terms and conditions: https://www.hatchwise.com/terms-and-conditions

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.hatchwise.com/privacy-policy

Revenue model

Contest pricing: https://www.hatchwise.com/contest-pricing

Our money back guarantee: https://www.hatchwise.com/guarantee

Also see link under terms and conditions.

Recruitment and matching

See link under contest pricing.

Work processes and performance management

The Hatchwise learning center: https://www.hatchwise.com/resources

Frequently asked questions: https://www.hatchwise.com/frequently-asked-questions

Rules of platform governance

See links under terms and conditions, and frequently asked questions.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

12

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Competitive programming platforms

CodeChef

Terms of service: https://www.codechef.com/terms

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.codechef.com/privacy-policy

Revenue model

Refund policy: https://www.codechef.com/refund-policy

Guidelines: https://www.codechef.com/problemsetting

Setting: https://www.codechef.com/problemsetting/setting

Testing: https://www.codechef.com/problemsetting/testing

CodeChef business: https://business.codechef.com

Ranking/ratings

Rating mechanism: https://www.codechef.com/ratings

Recruitment and matching

Create your CodeChef account: https://www.codechef.com/signup

Code of conduct: https://www.codechef.com/codeofconduct

Also see links under guidelines, setting, testing, and ranking/ratings.

Work processes and performance management

How does CodeChef test whether my solution is correct or not?: https://discuss.codechef.com/t/

how-does-codechef-test-whether-my-solution-is-correct-or-not/332

Also see links under guidelines, setting, testing, and code of conduct.

Rules of platform governance

See links under terms of service, setting, testing, and code of conduct.

HackerEarth

Terms of service: https://www.hackerearth.com/terms-of-service/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.hackerearth.com/privacy/

Revenue model

Pricing: https://www.hackerearth.com/recruit/pricing/

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.hackerearth.com

Also see link under pricing.

Rules of platform governance

What is HackerEarth’s plagiarism policy?: https://help.hackerearth.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360002921714-What-is-HackerEarth-s-plagiarism-policy-

Also see link under terms of service.

HackerRank

Terms of service: https://www.hackerrank.com/terms-of-service

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.hackerrank.com/privacy

Revenue model

Pricing: https://www.hackerrank.com/products/pricing/?h_r=pricing&h_l=header

Ranking/ratings

Scoring documentation: https://www.hackerrank.com/scoring

Recruitment and matching

Sign up: https://www.hackerrank.com/auth/signup?h_l=body_middle_left_button&h_r=sign_up

Also see links under terms of service and revenue model.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

13

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Competitive programming platforms (cont’d)

Kaggle

Terms of use: https://www.kaggle.com/terms

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.kaggle.com/privacy

Revenue model

Meet Kaggle: https://www.kaggle.com/static/slides/meetkaggle.pdf?Host_Business

Also see link under terms of use.

Ranking/ratings

Kaggle progression system: https://www.kaggle.com/progression

Recruitment and matching

Sign in: https://www.kaggle.com/account/login?phase=startRegisterTab&returnUrl=%2Fterms

Also see link under terms of use.

Work processes and performance management

Community guidelines: https://www.kaggle.com/community-guidelines

Courses: https://www.kaggle.com/learn/overview

Rules of platform governance

Why has my account been blocked: https://www.kaggle.com/contact

Also see links under terms of use, meet Kaggle, and community guidelines.

Topcoder

Terms and conditions: https://www.topcoder.com/community/how-it-works/terms/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.topcoder.com/policy/privacy-policy

Revenue model

Enterprise: https://www.topcoder.com/enterprise-oerings/

Talent as a service: https://www.topcoder.com/enterprise-oerings/talent-as-a-service/

Ranking/ratings

Algorithm competition rating system: https://www.topcoder.com/community/competitive-programming/

how-to-compete/ratings

Development reliability ratings and bonuses: https://help.topcoder.com/hc/en-us/

articles/219240797-Development-Reliability-Ratings-and-Bonuses

Recruitment and matching

Log in to Topcoder: https://accounts.topcoder.com/member

Also see links under terms and conditions, revenue model, and algorithm competition rating system.

Work processes and performance management

Community code of conduct: https://www.topcoder.com/community/topcoder-forums-code-of-conduct/

Account policies: https://www.topcoder.com/thrive/articles/Topcoder%20Account%20Policies

Rules of platform governance

Cheating infractions and process: https://www.topcoder.com/thrive/articles/Cheating%20Infractions%20&%20

Process

Non-Disclosure Agreement (NDA): https://www.topcoder.com/thrive/articles/Non%20Disclosure%20Agreement%20

(NDA)

Also see links under terms and conditions, account policies, and community code of conduct.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

14

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Microtask platforms

Amazon

Mechanical

Turk

Participation agreement: https://www.mturk.com/participation-agreement

For data collection and usage see the privacy notice: https://www.amazon.com/gp/help/customer/display.html/

ref=footer_privacy?ie=UTF8&nodeId=468496

Revenue model

Pricing: https://www.mturk.com/pricing

Amazon Mechanical Turk pricing: https://requester.mturk.com/pricing

Amazon pay fees: https://pay.amazon.com/help/201212280

FAQs: https://www.mturk.com/worker/help

Also see link under participation agreement.

Ranking/ratings

Qualications and worker task quality: https://blog.mturk.com/

qualications-and-worker-task-quality-best-practices-886f1f4e03fc

New feature for the MTurk marketplace: https://blog.mturk.com/

new-feature-for-the-mturk-marketplace-aaa0bd520e5b

Also see link under FAQs.

Recruitment and matching

See links under participation agreement, privacy notice, revenue model, FAQs, pricing, and qualications and

worker task quality.

Work processes and performance management, and rules of platform governance

See links under participation agreement and FAQs.

Clickworker

For the terms and conditions and privacy policy see: https://www.clickworker.com/terms-privacy-policy/

Revenue model

Pricing: https://www.clickworker.com/pricing/

Clickworker FAQ: https://www.clickworker.com/faq/

Customer FAQ: https://www.clickworker.com/customer-faq/

Survey participants for online surveys: https://www.clickworker.com/

survey-participants-for-online-surveys/#fee-recommendations

Recruitment and matching

Qualications at Clickworker: https://www.clickworker.com/crowdsourcing-glossary/qualications-at-clickworker/

What does a Clickworker do?: https://www.clickworker.com/clickworker-job/#distribution

Clickworker starts new SMS account verication system: https://www.clickworker.com/2014/05/08/sms_verication/

Also see links under terms and conditions and privacy policy, Clickworker FAQ, and customer FAQ.

Work processes and performance management, and rules of platform governance

See links under terms and conditions and privacy policy, Clickworker FAQ, and customer FAQ.

Appen

Legal terms: http://f8-federal.com/legal/

Revenue model

Frequently asked questions: https://success.appen.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115000832063-Frequently-Asked-Questions

Also see link under legal terms.

Recruitment and matching

Glossary of terms: https://success.appen.com/hc/en-us/

articles/202703305-Getting-Started-Glossary-of-Terms#tainted_judgment

Guide to: test question settings (quality control): https://success.appen.com/hc/en-us/

articles/202702975-Test-Questions-Settings

Also see link under frequently asked questions.

Work processes and performance management

Guide to quality control page: https://success.appen.com/hc/en-us/articles/201855709

Also see links under legal terms and recruitment and matching.

Rules of platform governance

See links under legal terms, frequently asked questions, glossary of terms, guide to: test question settings (quality

control), and guide to: quality control page.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

15

A) Online web-based platforms (cont’d)

Microtask platforms (cont’d)

Microworkers

Terms of use: https://www.microworkers.com/terms.php

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.microworkers.com/privacy.php

Revenue model

FAQ: https://www.microworkers.com/faq.php

Guidelines FAQ: https://www.microworkers.com/faq-guidelines.php

Also see link under terms of use.

Recruitment and matching, and work processes and performance management

See links under FAQ and guidelines FAQ.

Rules of platform governance

See links under terms of use, FAQ, and guidelines FAQ.

B) Location-based platforms

Taxi platforms

Bolt (Taxify) Ghana

Kenya

General terms for drivers: https://bolt.eu/en/legal/terms-for-drivers/

Terms and conditions for passengers: https://bolt.eu/en/legal/terms-for-riders/

For data collection and usage see:

Privacy policy for drivers: https://bolt.eu/en/legal/privacy-for-drivers/

Privacy policy for passengers: https://bolt.eu/en/legal/privacy-for-riders/

Revenue model

Commission fee: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/articles/115002946374-Commission-Fee

Driver paid wait time fees: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360009458774-Driver-Paid-Wait-Time-Fees

Issue with a cancellation fee: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360009457274?ash_digest=7dcc15def68f2cf475d9152c23ca169b44e11f2f

Damage or cleaning fee: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360003640779-Damage-or-Cleaning-Fee

Also links under general terms for drivers and terms and conditions for passengers.

For Ghana: Driver payouts and commission: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360001892993-Driver-Payouts-and-Commission

For Kenya: Driver balance and commission: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360010650180-Driver-Balance-and-Commission

Ranking/ratings

Activity score calculation: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/115002946174-Activity-Score-Calculation

Acceptance rate calculation: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/360007690199-Acceptance-Rate-Calculation

Rating a passenger: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/115002907553-Rating-a-Passenger

How to leave a rating: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/articles/115002918034-Rating-a-Ride

Also see link under general terms for drivers.

Recruitment and matching

Becoming a Bolt driver: https://support.taxify.eu/hc/en-us/

articles/115003390894-Becoming-a-Bolt-Driver

Also see link under general terms for drivers.

Work processes and performance management, and rules of platform governance

See links under general terms for drivers, terms and conditions for passengers, activity score

calculation, and acceptance rate calculation.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

16

B) Location-based platforms (cont’d)

Taxi platforms (cont’d)

Careem Morocco

Terms of service: https://www.careem.com/en-ma/terms/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.careem.com/en-ma/privacy/

Revenue model

How do I refer a friend?: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360001609527-How-do-I-refer-a-friend-

What do starting, time, distance, minimum and promised

fare mean?: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360001400007-What-do-Starting-Time-Distance-Minimum-and-Promised-fare-mean-

Cancelling a ride: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001600367-Cancelling-a-ride

Also see link under terms of service.

Recruitment and matching

Drive with Careem: https://drive.careem.com

How do I create a Careem account?: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360001609507-How-do-I-create-a-Careem-account-

What is in ride insurance? https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/

articles/115010884527-What-is-in-ride-insurance-

Also see link under terms of service.

Work processes and performance management

In-ride standards: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/articles/360001609427-In-ride-Standards

Also see link under terms of service.

Rules of platform governance

How does an account get blocked or suspended?: https://help.careem.com/hc/en-us/

articles/360001609447-How-does-an-account-get-blocked-or-suspended-

Also see link under terms of service.

Gojek Indonesia

Terms of use: https://www.gojek.com/terms-and-condition/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.gojek.com/privacy-policies/

Recruitment and matching

Join as our GoRide driver: https://www.gojek.com/help/mitra/

bergabung-menjadi-mitra-go-ride/

Also see links under terms of use and privacy policy.

Singapore

User terms of use: https://www.gojek.com/sg/terms-and-conditions/

Driver services agreement: https://www.gojek.com/sg/driver/agreement/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.gojek.com/sg/privacy-policy/

Revenue model

What is the Gojek Service Fee?: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/?q=service+fee

Also see links under user terms of use and driver services agreement.

Ranking/ratings

How do ratings work?: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/service/#how-do-ratings-work

Recruitment and matching

What documents will I need to upload?: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/

account/#what-documents-will-i-need-to-upload

What can I drive with on Gojek: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/

account/#what-can-i-drive-with-on-gojek

GoFleet: https://www.gojek.com/sg/driver/goeet/

Also see links under user terms of use, driver services agreement, and privacy policy.

Work processes and performance management

Driver code of conduct: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/driver-code-of-conduct

Also see links under user terms of use and driver services agreement.

Rules of platform governance

Can I share my Gojek account with Others?: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/

account/#can-i-share-my-gojek-account-with-others

I was suspended due to inactivity: https://www.gojek.com/sg/help/driver/

account/#i-was-suspended-due-to-inactivity

Also see links under user terms of use and driver services agreement.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

17

B) Location-based platforms (cont’d)

Taxi platforms (cont’d)

Grab Indonesia

Terms of service: transport, delivery, and logistics: https://www.grab.com/id/en/terms-policies/

transport-delivery-logistics/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.grab.com/id/en/terms-policies/

privacy-policy/

Revenue model

Grab referral programme terms and conditions: https://www.grab.com/id/en/pax-refer-friend/

privacy/

GrabFood – partner with us: https://www.grab.com/id/en/merchant/food/

Also see link under terms of service.

Recruitment and matching

Register now: https://www.grab.com/id/en/driver/transport/car/

Also see links under terms of service, privacy policy and GrabFood partner with us.

Singapore

Terms of service - transport, delivery and logistics: https://www.grab.com/sg/terms-policies/

transport-delivery-logistics/

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.grab.com/sg/terms-policies/

privacy-policy/

Revenue model

FAQs: https://www.grab.com/sg/driver/transport/car/faq/

Updated cancellation policy from 25 Mar 2019: https://help.grab.com/passenger/en-

sg/115008318688; https://www.grab.com/sg/passenger-cancellation-fees/

I was charged a cancellation fee: https://help.grab.com/passenger/

en-sg/115005276987-I-was-charged-a-cancellation-fee

What are grace waiting periods and waiting fees: https://help.grab.com/passenger/

en-sg/360035841031-What-are-grace-waiting-periods-and-waiting-fees

#AskGrab: where does the Merchant commission go?: https://www.grab.com/sg/blog/

askgrab-where-does-the-merchant-commission-go/

How do I refer?: https://www.grab.com/sg/gfm-referral/

Also see link under terms of service.

Ranking/ratings

Acceptance and cancellation rating: https://help.grab.com/driver/

en-sg/115013368427-Acceptance-and-Cancellation-rating

Recruitment and matching

Drive: https://www.grab.com/sg/driver/drive/

Deliver: https://www.grab.com/sg/driver/deliver/

Drive with Grab using your own car in 4 Steps: https://www.grab.com/sg/

drive-with-grab-using-your-own-car/

Also see links under terms of service and privacy policy.

Work processes and performance management

How to improve my star rating: https://help.grab.com/driver/

en-sg/115015441428-Driver-Rating-How-is-this-calculated

Also see link under terms of service.

Little Kenya

Terms and conditions: https://www.little.bz/ke/tnc.php

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

The role of digital labour platforms in transforming the world of work

18

B) Location-based platforms (cont’d)

Taxi platforms (cont’d)

Ola India

Subscription agreement: https://partners.olacabs.com/public/terms_conditions

Terms and conditions: https://www.olacabs.com/tnc?doc=india-tnc-website

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://www.olacabs.com/

tnc?doc=india-privacy-policy

Revenue model

Why is cancellation fee charged: https://help.olacabs.com/support/dreport/208298769

Also see links under subscription agreement and terms and conditions.

Ranking/ratings

How can I rate a ride?: https://help.olacabs.com/support/dreport/205098571

Recruitment and matching

Drive with Ola: https://partners.olacabs.com/drive

Lease a car: https://partners.olacabs.com/lease

Ola rolls out ‘Chalo Bekar’ comprehensive insurance program for

its driver partners: https://www.olacabs.com/media/in/press/

ola-rolls-out-chalo-bekar-comprehensive-insurance-program-for-its-driver-partners

Ola oers coverage of up to Rs. 30,000 for driver-partners and their spouses aected by COVID-19;

also brings free medical help for their families: https://www.olacabs.com/media/in/press/

ola-oers-coverage-of-up-to-rs-30000-for-driver-partners-and-their-spouses-aected-by-

covid-19-also-brings-free-medical-help-for-their-families

Also see link under subscription agreement.

Uber Argentina

Chile

Ghana

India

Kenya

Lebanon

Mexico

Morocco

United States

For the general terms of use, privacy notice, and general community guidelines see: https://

www.uber.com/legal/en/ (“Uber legal”) – select the relevant policy in the link and then the

relevant country.

Revenue model

For Ghana: tracking your earnings: https://www.uber.com/gh/en/drive/basics/

tracking-your-earnings/

Wait time fees: https://help.uber.com/riders/article/

wait-time-fees?nodeId=5960f72c-802a-4b61-a51c-2c9498c3b041

Am I charged for cancelling an Uber ride?: https://help.uber.com/riders/article/

am-i-charged-for-cancelling-an-uber-ride-?nodeId=5f6415dc-dfdb-4d64-927a-66bb06bc4f82

Also see links under Uber legal.

Recruitment and matching

Vehicle requirements: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/

vehicle-requirements?nodeId=2ddf30ca-64bd-4143-9ef2-e3bc6b929948

What does the background check look for: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/

what-does-the-background-check-look-for?nodeId=ee210269-89bf-4bd9-87f6-43471300ebf2

Why am I being asked to take a photo of myself?: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/

article/why-am-i-being-asked-to-take-a-photo-of-myself--?nodeId=7fa8a60d-cf6f-49ac-9a50-

b4bf6a3978ef

Getting a trip request: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/

getting-a-trip-request?nodeId=e7228ac8-7c7f-4ad6-b120-086d39f2c94c

When and where are the most riders?: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/

when-and-where-are-the-most-riders?nodeId=456fcc51-39ad-4b7d-999d-6c78c3a388bf

Insurance: https://help.uber.com/driving-and-delivering/article/

insurance-?nodeId=a4afb2ed-75af-4db6-8fdb-dccecfcc3fd7

Also see link under Uber legal.

Work processes and performance management

Can I use other apps or receive personal calls while online?: https://help.uber.com/

driving-and-delivering/article/can-i-use-other-apps-or-receive-personal-calls-while-online---

?nodeId=a5a7c0c7-da4b-46af-a180-7ad1d2590234

Also see link under Uber legal.

X

Table A2.2 (cont’d)

Appendix 2. ILO interviews with digital platform companies and analysis of terms of service agreements

19

B) Location-based platforms (cont’d)

Delivery platforms

Cornershop Mexico

Terms of use: https://cornershopapp.com/en/terms

For data collection and usage see the privacy policy: https://cornershopapp.com/es-mx/privacy

Revenue model

Cornershop for stores: https://cornershopapp.com/en/stores?adref=customer-landing

Cornershop Pop, la membresía de envíos gratis ilimitados: https://blog.cornershop.mx/

cornershop-pop-la-membresia-de-envios-gratis-ilimitados-mx/

Also see link under terms of use.

Deliveroo France

Conditions generales de prestation de service de Deliveroo: https://deliveroo.fr/en/legal

For data collection and usage see politique de condentialité de Deliveroo France: https://deliveroo.

fr/en/privacy

Revenue model

Comment suis-je payé ?: https://riders.deliveroo.fr/fr/support/nouveaux-livreurs-partenaires/

vous-etes-payes-pour-chaque-livraison-eectuee.-les

Also see links under conditions generales de prestation de service de Deliveroo, and politique

de condentialité de Deliveroo France.

Recruitment and matching

Ride with us: https://deliveroo.fr/en/apply

Nouveaux livreurs partenaires: https://riders.deliveroo.fr/fr/support/

nouveaux-livreurs-partenaires

Gérer votre entreprise: https://riders.deliveroo.fr/fr/support/gerer-votre-entreprise

Assurances Deliveroo: https://riders.deliveroo.fr/fr/support/toutes-vos-assurances-deliveroo

Also see links under conditions generales de prestation de service de Deliveroo, and politique

de condentialité de Deliveroo France.

United Kingdom

Terms of service: https://deliveroo.co.uk/legal

Scooter supplier agreement: https://old.parliament.uk/documents/commons-committees/work-