1

F

21 March 2023

Investigative Report 23-03

Douglas R. Hoffer Vermont State Auditor

Universal Broadband in

Vermont:

Managing Risks

2

Mission Statement: The mission of the Auditor’s Office is to hold State

government accountable by evaluating whether taxpayer funds are

being used effectively and identifying strategies to eliminate waste,

fraud, and abuse.

Investigative Report: An investigative report is a tool used to inform

citizens, policymakers, and State agencies about issues that merit

attention. It is not an audit and is not conducted under generally

accepted government auditing standards. Unlike an audit, which

contains formal recommendations, investigative reports include

information and possible risk-mitigation strategies relevant to the topic

that is the object of the inquiry.

Principal Investigator: Ilan Weitzen, Government Research Analyst

3

Introduction

Since at least the mid-2000s,

Vermont policymakers have

recognized that high-quality

broadband infrastructure is

essential to promoting

economic growth,

employment and educational

opportunities, public health

and safety networks, and

social and civic engagement.

Despite broad agreement

about the need for

ubiquitous broadband,

progress has been slow.

While Vermont’s population

centers generally feature at

least one broadband

provider, 19 percent of

Vermont addresses do not have access to 25/3 megabits per second (Mbps) service (the federal

definition of broadband). More troubling, 70% of Vermont addresses lack 100/100 coverage, the state’s

goal for every address.

There are several primary reasons so many Vermonters have been unserved or underserved. First, for-

profit corporations have shown little interest in serving more rural, less profitable communities. Second,

and related to the first, the federal government has not required telecom companies to meet rural

areas’ broadband needs as they did with telephone service. Third, a Vermont telecom company, VTel,

received $116M during the Obama Administration to make coverage available to every unserved

address in Vermont. That effort failed. And fourth, Vermont did not identify a source of funds to make

more than incremental progress.

This report examines the State’s efforts to expand access to high-speed broadband since the onset of

the COVID-19 pandemic when the federal government provided funding to overcome the fourth barrier

described above. Much has been written and said about the state’s broadband goals. This report is

concerned with identifying risks that could impede successfully meeting those goals in the coming years.

Background

Concluding that existing broadband providers failed to achieve universal, reliable, high-quality service,

the Legislature sought to expand coverage through other means. In 2015, it authorized the creation of

multi-municipality Communications Union Districts (CUDs). CUDs were intended to develop, coordinate,

and implement broadband expansion in their respective territories, particularly where existing providers

have not provided adequate service (or any service) that meets the needs of residents and businesses.

CUDs allow towns to join forces and aggregate demand for broadband infrastructure to create

4

economies of scale while featuring an element of public accountability by virtue of representation of

each member municipality on a CUD’s board of directors. There are now 10 CUDs in varying stages of

development that together represent 214 municipalities.

State funding to further the CUDs’ efforts began in earnest

with the arrival of COVID and the substantial federal funds

that filled the state’s coffers. In June 2020, $800,000 from

the CARES Act was made available to CUDs for planning

activities. Separately, $12 million was granted to existing

internet service providers to extend broadband service to

unserved and underserved areas, prioritizing low-income

households who needed high-speed internet access during

the pandemic to learn remotely, telework, and access vital

medical services. An additional $2 million was dedicated to

help some Vermonters pay to connect their homes to

existing, nearby fiberoptic lines. As a result of these

investments, nearly 10,000 addresses gained access to high-

speed broadband.

A year later, with funds from the federal American Rescue

Plan (ARPA), the Legislature allocated $150 million to

support CUDs’ buildout efforts. At the same time, they passed Act 71, the law that created the Vermont

Community Broadband Board (VCBB) to coordinate, facilitate, and accelerate the implementation of the

State’s universal broadband goals. The VCBB was entrusted with granting the initial $150 million to the

CUDs. First, the CUDs were to receive preconstruction grants from the VCBB to fund comprehensive

studies of the infrastructure needed to create universal service in their geographic areas, and to develop

business plans utilizing private partnerships with internet service provider (ISP) operating partners.

Through subsequent construction grants, the CUDs would then be responsible for building out

broadband infrastructure over the next several years according to their VCBB-approved plans. To future-

proof the investments, only networks capable of at least 100 synchronous Mbps (100/100) would be

funded (only fiberoptic lines are capable of reliably achieving that standard at this time).

In 2022, the Legislature committed an additional $95 million to the VCBB to support Act 71’s broadband

goals. A minimum of an additional $100 million more, and as much as $250 million, is expected to be

made available through the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) signed into law by President

Biden in November 2021. This more than $350 million investment represents one of the largest

infrastructure projects in Vermont history, rivaling rural electrification and the Interstate Highways.

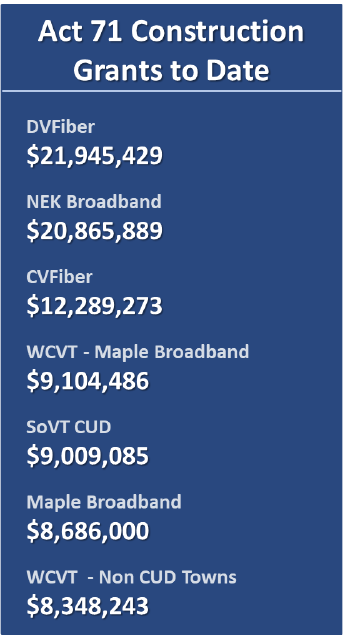

Since its inception, the VCBB has awarded $114.41 million in preconstruction and construction grants to

the CUDs and spent an additional $9.85 million for the bulk purchase of materials to avoid supply chain

issues and lower overall project costs. Six CUDs have commenced construction in their respective

territories.

5

Risks That Threaten Vermont’s Universal Broadband Goals

The risks below represent threats to Vermont’s ambitious plan to utilize the CUD model to deliver

universal, affordable broadband access to every Vermont address. These risks are informed by our

review of CUD contracts and grant agreements, VCBB, Vermont Communications Union District

Association, and CUD board meeting minutes and materials, dozens of interviews, and relevant

legislation.

Risk 1. Some CUDs Face a Potential Construction Funding Gap in Calendar Year 2024 Which Could

Halt Construction Mid-stride if Additional Funds Are Not Identified

The VCBB has identified several CUDs that, at present, would run out of construction funds after the

2023 building season. This would put construction on hold and could lead to higher project costs and

delayed service availability.

The gap will develop when CUDs’ ARPA grant monies run out and

the State awaits its share of federal Broadband Equity, Access, and

Deployment (BEAD) investments. Vermont is slated to receive a

minimum of $100 million, and up to $250 million, in BEAD funding

over the next two years, but it is uncertain when those funds will

become available. The initial payment to the State will amount to

just 20 percent of the total award, and the precise timing of its

arrival is unknown at this time. Even when the funds arrive, it may

take the VCBB and its consultants time to evaluate a new round of

grant applications.

Funding-related delays would be problematic for several reasons.

First, and most obviously, it will prolong the amount of time many

Vermonters wait for broadband service. Second, qualified

construction crews may select other work while the CUD waits for

funds, and may not return or be easily or promptly replaced. Third,

materials will likely be scarcer and more costly by the time funds

are in hand. And fourth, the CUDs’ business plans are based on

anticipated growth in subscribers (known as the take up rate). If the

plan anticipates paying customers being added throughout 2024,

but they are not hooked up, the lost revenue may pose cash flow problems and jeopardize operations

and further build out.

The VCBB, CUDs, and other stakeholders have suggested several possible ways to fill the potential

funding gap. They include:

* Creation of a $50 million revolving loan fund CUDs could draw from and replenish with their BEAD

allocation when it arrives.

6

* Seek infrastructure funds

from the Northern Borders

Regional Commission (NBRC)

to establish grants or low-

interest loans. [The NBRC is a

Federal-State partnership for

economic and community

development in northern

Maine, New Hampshire,

Vermont, and New York.]

* Use $30 million appropriated

in the FY 2023 Budget

Adjustment Act as a match

for Vermont’s $67 million

Middle Mile federal funding

request to supplement and

accelerate construction

efforts by the CUDs.

Whatever mechanism is chosen, the sooner it is established, the lower the risks involved.

Risk 2. CUDs May Struggle to Access Needed Construction Materials

Ensuring that CUDs have the necessary materials to construct their network is vital whether or not the

funding gaps described above occur. Demand for fiberoptic cable and other supplies will be heavy

throughout the country when $42.5 billion in BEAD funds are released. The sooner the necessary

materials are procured, the less risk that CUDs will face long wait times or inflated costs. Ideally, CUDs

would purchase materials this year for the 2024 season.

Risk 3. Construction May be Slowed by a Lack of Qualified Construction Workers

According to the VCBB, an additional 200 fiber technician workers are needed to support Vermont’s

broadband buildout. These new positions would join a labor market that is already unstable.

It is not clear how the VCBB concluded that 200 new positions are necessary, nor is it clear whether

those positions would still be needed once the fiber buildout has been completed. VCBB’s current

workforce development strategy centers around a training program designed in collaboration with the

Vermont State Colleges and other partners. This program

, plus the 2000 hours of apprenticeship the

VCBB says are needed before a new technician is proficient, may produce a cadre of new fiber techs

within a year or two, though the VCBB anticipates that for every three workers trained, one will elect to

pursue a different career path.

Before committing significant funds to broadband workforce training, policymakers should evaluate the

schedule of anticipated statewide buildout and determine whether such training programs are capable

of bringing new workers on-line in time to be useful. The cost of such training should be evaluated in

comparison to paying premium rates to existing workers or vendors to encourage them to take on this

7

work. Existing utility workers also present a

possible alternative to lengthy and costly training

programs. Partnerships with Vermont utilities

should be evaluated to determine whether utility

and CUD construction schedules could be

coordinated in order to deploy skilled workers who

already have comparable training, either by

contracting with the utilities or extending the offer

of secondary work to utility employees.

Risk 4. The Tension Between the VCBB Supporting the CUDs and Ensuring They are Viable Risks

Allowing Any Weaknesses in CUD Business Plans to Persist and Deepen

Act 71 requires the VCBB to ensure that each CUD has a viable business plan in place prior to granting

them funds. According to the VCBB, VCBB staff and Board members and a contracted third-party

consulting firm review and subject the business plans to stress testing to make certain they are

financially sustainable. Nonetheless, VCBB staff analysis has acknowledged the uncertainties inherent in

the state’s unique approach to broadband buildout and in external factors like federal funding rules. For

instance, VCBB staff have speculated that a time could come when two or more CUDs may be more

viable in the long run if they merge with one another due to demographic and infrastructure

considerations that risk the standalone CUD’s failure.

The VCBB has the authority to condition its grant awards to CUDs as it sees fit to achieve the state’s

broadband goals. The VCBB must apply continuous and rigorous scrutiny of CUD business plans to avoid

squandering the substantial, one-time funding driving the state’s efforts. And whether the VCBB directs

two or more CUDs to merge as a funding condition, or if CUDs elect to merge of their own accord, the

VCBB should anticipate this possibility by developing merger documents, so they do not need to be

drafted on the fly or under duress.

Risk 5. Reliance Upon CUDs with Varying Levels of Expertise and Capacity May Delay Broadband

Service to Some Vermonters, Lead to Increased Spending, and Establish Inequitable Policies

and Access

The VCBB’s executive director frequently remarks that the Board’s work has been akin to building a

plane while flying it. The same may also be said of the CUDs. In each case, an entity was established,

then required to hire staff and develop processes, all with the specter of deadlines for expending funds

hovering over their endeavors. As a result, the VCBB was not in a position to apply a robust, mature

oversight function over CUDs from the onset. Similarly, some CUDs were making business decisions in

the absence of professional staff, and without the benefit of the technical assistance the VCBB and a

maturing Vermont Communication Union District Association (VCUDA, the CUDs’ trade association) can

now offer.

8

The VCBB conducted a Grantee Risk-Based

Assessment of each CUD before considering

applications for preconstruction and construction

grant awards, as required by the State. In every

instance, the CUDs were determined to be high-

risk grantees, largely due to having little or no

track record receiving and administering grant

funds. For this and other factors, activities to date

have not always been smooth, as illustrated by

these examples:

• While the VCBB’s 2023 Legislative Report

indicates that existing grant agreements

address methods to support low-income

and disadvantaged communities, we have

not found any such language in the

agreements.

• The VCBB has relied, in part, on surveys

and self-attestations from the CUDs

regarding their own capacity, financials,

and reporting when considering funding awards despite their high-risk classification. Self-

attestations fall far short of the verification standard detailed in the Department of Finance and

Management’s Internal Control Standards: A Guide for Managers

.

• Despite its broad powers to be more directive, the Board has given CUDs freedom to make

business decisions that vary in terms of staffing, cost, strategy, negotiations, and public

disclosure/confidentiality. As a result, CUD activities may not always reflect the most efficient

and publicly beneficial use of public funds.

• At least two CUDs based their initial business plans upon the anticipated service take rate and

financials of another CUD even though they have different demographic and geographic

concerns.

• Though their grant agreements require monthly reporting to the VCBB, multiple CUDs submitted

reports that were late and lacking useful detail with regard to scope and scale.

While more than $110 million of public funds have been awarded under the initial, looser oversight

framework, a more comprehensive framework is being developed by Public Service Department grant

administration staff for consideration and adoption by the VCBB. The recommended oversight plan

includes a combination of desk and on-site monitoring methods, including compliance with:

• CUDs’ statutory requirements in terms of governing board composition and competency,

meeting records, bylaws.

• Federal administrative requirements such as conflict of interest policies, cost allocation

methodology, and procurement and internal control processes

9

The VCBB has also updated its monthly reporting requirement to obtain consistent, timely, and salient

information from CUDs.

The VCBB should adopt the new oversight framework as soon as possible so that the hundreds of

millions in future awards will be subject to a higher standard of public accountability.

Risk 6. With the Exception of the Early VCBB Fiber Purchase, CUDs Have Not Been Partnering for

Procurement of Goods and Services, Risking Higher Costs and Inferior Outcomes

Each CUD has, to this date, individually procured goods and services such as administrative support,

legal, and accounting. This raises the risk CUDs will pay varying costs for the same goods and services

with no public benefit or justification. It also limits the benefits of sharing the highest quality vendors to

perform comparable analysis and functions. In recognition of this, the VCBB and VCUDA recently

secured a grant of $2.5 million from the Northern Borders Regional Commission (NBRC) to fund an

initiative they have called the “Securing the Public Interest Through Shared Expertise and Services

Program”. The stated goals of the program include ensuring efficiency, accountability, and resilience in

the face of market challenges. The grant will fund positions for experts in the field who will mostly be

housed at VCUDA. These new “shared” staff will

conduct a needs analysis of shared services, and will

support CUDs in program management, policy

analysis, accounting, communications, and make

ready support. These roles have been funded for $2.1

million across three years. The VCBB and VCUDA

project that after year three CUD revenues will be

sufficient to sustain the shared positions.

There is a tension between combining services whenever possible and the autonomy of each CUD. The

VCBB will need to determine the extent to which it conditions its funding on the most efficient use of its

grant funds, even when that removes the options available to individual CUDs. For example, the VCBB

must decide whether it wishes to require CUDs to jointly purchase fiberoptic cable as a condition of

funding or to use a shared grant administrator.

Risk 7. Statutory Confidentiality Provisions Shield Some CUD Decision-making from the VCBB,

Policymakers and Residents of the Member Municipalities Despite Receiving Tens of

Millions in Public Funds

The CUDs have frequently invoked their statutory right to treat contracts and some other internal

documents as confidential or protected by attorney-client privilege even when it has prevented them

from receiving expert advice, though confidentiality concerns could be addressed with redactions or

nondisclosure agreements. This raises risks that CUDs will agree to provisions with their internet service

provider partners that are suboptimal from the point of view of end users and the taxpayers whose

funds are fueling their broadband buildout. Instances of contract provisions that are not being made

available for public inspection include:

10

• Proposed pricing plans.

• Requirements around public access programming and other

content.

• Service quality expectations.

CUDs are largely operating in unserved areas, and yet they are

concerned that public disclosure could allow for-profit

competitors who’ve previous ignored rural areas to swoop in

and undermine the CUDs’ business plans. While we cannot

judge the extent to which that fear is warranted, we do believe

the tendency, to date, to withhold key contractual elements

that will impact the end user raises the risk that anticipated

service take rates will not be as accurate as they should be, and

that users may be surprised to learn, when service arrives, that

certain policies have been locked in place by virtue of multi-

year contracts with service providers. CUDs’ member

municipalities each have a representative on their respective

CUD board of directors, but if those representatives do not seek

feedback from their fellow residents on key customer issues (or

are prevented from doing so by confidentiality provisions) such

as those bulleted above there is a risk that subscription rates

will not meet expectations.

Risk 8. Lack of Affordability Definitions and Requirements Threaten to Reduce Service Connections,

Undermine CUD Business Plans, and Create Regional Inequities

Act 71 directed the VCBB to give priority to applicants for broadband project funding that “provide

consumers with affordable service options.” Ensuring that Vermonters will be able to afford high-speed

broadband once it becomes available to them is central to the State’s universal service plan requirement

under Act 71 and the mission of the VCBB. While the CUDs are obligated to submit a plan to provide

low-income subscribers with affordable service options, specifically by referring them to a federal FCC

subsidy program, what affordability means for businesses and families has not been defined by the

Legislature or the Board. CUDs’ business plans assume service take rates from low- and moderate-

income households. If not enough low- and moderate-income Vermonters sign-up for plans because

they are deemed unaffordable, those who have subscribed will need to pay more to ensure sufficient

revenues for the CUDs to remain profitable.

Furthermore, high-speed plans available in more populous areas often range between $55-80/month

and have already proven a barrier to many households. In more rural communities with a smaller

customer base per mile of fiber, service costs could be even higher, putting more pressure on the

monthly subscription prices.

The Affordable Connectivity Program (ACP) administered by the FCC limits assistance to households with

incomes below 200% of the poverty line to a subsidy of $30/month to help pay for internet service.

11

Therefore, in Vermont, only families of four with incomes below $60,000/year are eligible; and for

families of two, income must be below $39,440. Established with $14 billion dollars from the American

Rescue Plan, the ACP is currently the only subsidy available to Vermont consumers and the funding is

slated to run out in 2024 unless it is renewed by Congress. Even with this consumer subsidy, it is not

clear that a discount of $30/month on a bill that may otherwise approach $100/month will be sufficient

for many Vermonters to sign up for service.

Because neither the authorizing legislation nor the VCBB have defined affordability, it is possible that

each CUD will establish its own definition of the term. It seems unlikely that the Legislature intended

that two like CUDs, building out in comparable communities, would charge customers at rates that may

vary greatly.

If this issue is not addressed before buildout occurs and further funds are awarded, attempts to remedy

the “affordability” issue will be difficult to implement since CUDs’ business plans and contractual

arrangements with internet service providers will be more or less locked in place. It raises the prospect

that policymakers will be asked to make annual appropriations from the state budget to subsidize

service which has previously been a matter for the providers to address.

Risk 9. The Firm the VCBB Employs to Evaluate CUD Business Plans Has Also Consulted for a CUD

and Does Not Appear to be Prohibited from Consulting for Others, Raising Conflict of

Interest Risks

VCBB has contracted with the firm CTC to perform independent evaluations of CUD business plans.

However, in addition to their work for the VCBB, CTC was contracted to provide consulting services to

the SoVT CUD before the VCBB awarded SoVT CUD $9 million in construction grant funds. Furthermore,

CTC bid on other CUDs’ requests for proposals.

The VCBB’s contract with CTC relies solely upon the 23

rd

provision of the state’s standard conflict of

interest language to address the conflict of interest risk described above. That provision reads:

“Conflict of Interest: Party shall fully disclose, in writing, any conflicts of interest or potential conflicts

of interest.”

It is not unusual, though, for contracts to include additional, case-specific processes allowing a

contractor to perform related work for another client while safeguarding against real or apparent

conflicts of interest. Contractors, especially larger ones, are capable of compartmentalizing their work

teams to mitigate conflict of interest concerns.

CTC’s services include advising the VCBB as they consider CUDs’ funding requests. In that context, the

ability of CTC or any other VCBB contractor to provide consulting services to a CUD should be

transparently addressed in order to maintain the public’s confidence that the VCBB is receiving truly

independent analyses of CUDs.

Risk 10. BEAD’s Irrevocable Letter of Credit Requirement is Not Designed for New and Small

Telecommunications Entities

Though BEAD funds are intended to be accessible by telecommunications entities of varying scale and

history, the program’s Irrevocable Line of Credit requirement presents a challenge for new and small

12

entities who are unlikely to have the acceptable forms of collateral needed to access the funds. VCBB

staff are seeking a waiver of this requirement from the National Telecommunications and Information

Administration (NTIA), the BEAD program’s administrative agency. If the waiver is not granted, a means

of establishing acceptable collateral will need to be developed, which risks Vermont’s BEAD funds not

being deployed in a timely manner.

Conclusion

The Vermont Community Broadband Board and their staff have (1) stood up an administrative agency,

(2) supported the development of ten newly created Communications Union Districts, and (3)

distributed more than $110 million for broadband planning and construction, all since the summer of

2021. The speed and nature of the undertaking has resulted, at times, in accountability and risk

mitigation strategies being developed after dollars are awarded, rather than before. If current estimates

are correct, the total cost to build a universal broadband network in Vermont will be between $600-800

million. The VCBB hopes 60% of those funds will come in the form of state, federal, or private grants.

The risks identified in this report do not represent an exhaustive list, but represents factors that, if left

unaddressed, could jeopardize Vermont meeting its broadband goals.