This paper is included in the Proceedings of the

31st USENIX Security Symposium.

August 10–12, 2022 • Boston, MA, USA

978-1-939133-31-1

Open access to the Proceedings of the

31st USENIX Security Symposium is

sponsored by USENIX.

Security and Privacy Perceptions of Third-Party

Application Access for Google Accounts

David G. Balash, Xiaoyuan Wu, and Miles Grant,

The George Washington University; Irwin Reyes, Two Six Technologies;

Adam J. Aviv, The George Washington University

https://www.usenix.org/conference/usenixsecurity22/presentation/balash

Security and Privacy Perceptions of

Third-Party Application Access for Google Accounts

David G. Balash

The George Washington University

Xiaoyuan Wu

The George Washington University

Miles Grant

The George Washington University

Irwin Reyes

Two Six Technologies

Adam J. Aviv

The George Washington University

Abstract

Online services like Google provide a variety of application

programming interfaces (APIs). These online APIs enable

authenticated third-party services and applications (apps) to

access a user’s account data for tasks such as single sign-on

(SSO), calendar integration, and sending email on behalf of

the user, among others. Despite their prevalence, API access

could pose significant privacy and security risks, where a third-

party could have unexpected privileges to a user’s account. To

gauge users’ perceptions and concerns regarding third-party

apps that integrate with online APIs, we performed a multi-

part online survey of Google users. First, we asked

n = 432

participants to recall if and when they allowed third-party

access to their Google account: 89% recalled using at least

one SSO and 52% remembered at least one third-party app.

In the second survey, we re-recruited

n = 214

participants

to ask about specific apps and SSOs they’ve authorized on

their own Google accounts. We collected in-the-wild data

about users’ actual SSOs and authorized apps: 86% used

Google SSO on at least one service, and 67% had at least one

third-party app authorized. After examining their apps and

SSOs, participants expressed the most concern about access to

personal information like email addresses and other publicly

shared info. However, participants were less concerned with

broader—and perhaps more invasive—access to calendars,

emails, or cloud storage (as needed by third-party apps). This

discrepancy may be due in part to trust transference to apps

that integrate with Google, forming an implied partnership.

Our results suggest opportunities for design improvements to

the current third-party management tools offered by Google;

for example, tracking recent access, automatically revoking

access due to app disuse, and providing permission controls.

1 Introduction

The 2018 Cambridge Analytica scandal [

23

] prompted the

scrutiny of third-party apps that integrate with online applica-

tion programming interfaces (APIs). This came about when

an online personality quiz used the Facebook API to collect

detailed personal information from millions of unsuspecting

quiz-takers and their friends. In response, Facebook restricted

how third-parties can use its API [

34

]. However, Facebook is

not unique among online services that allow third-party apps

to leverage user account data via APIs.

Likewise, Google has APIs that allow third-party services

to use existing user account data. For example, Google’s

single sign-on (SSO) [

18

] lets users log onto participating

third-party services with their already-existing Google creden-

tials. Other major online services like Apple [

4

], Twitter [

38

],

and Facebook [

8

] offer similar SSO capabilities using their

accounts.

The Google API also exposes functionality from various

Google products. For instance, APIs let authenticated third-

party apps to interact with Google Calendar entries or Gmail

correspondence on behalf of the user. This particular integra-

tion is what enables iOS’s built-in Calendar app to display

and edit a user’s Google Calendar events, among others.

Despite many benefits, granting programmatic access to

one’s online account can pose security and privacy risks, as

highlighted by Cambridge Analytica. In 2018, Google pro-

posed granular permissions for API authorizations to give

users more control and mitigate these risks [

17

]. As of

September 2021, however, this updated design does not ap-

pear to be widely adopted. Google API integrations in popular

services like Dropbox and Zoom still use all-or-nothing con-

sent flows, and a spot check of the most popular apps on

the Google Workspace Marketplace

1

shows those too lack

fine-grained permissions.

In this paper we explore how users consider security and

privacy in light of third-party API access to their Google ac-

counts given the disclosure and control mechanisms currently

available. First, we surveyed

n = 432

participants to recall

the last times they used Google SSO or authorized a third-

party app access to their Google account data. When recalling

these, we also asked participants what factors they considered

before granting access. Of the 432 participants, the vast ma-

jority (89%) recalled using SSO, but only half (52%) recalled

1

https://workspace.google.com/marketplace/category/popular-apps

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3397

granting the third-party access to their Google account.

We then invited

n = 214

participants from the first survey

to return for a follow-up survey. As part of this second survey,

participants installed a browser extension that parsed entries

in their Google account’s “Apps with access to your account”

dashboard.

2

Based on this data, we asked participants about

specific apps they currently have installed on their Google

account. From the browser extension, we observed 1,010

third-party services that use Google SSO and 455 third-party

apps that integrate with APIs for various Google services. Of

the observed third-party apps, nearly half require two or more

permissions accessing the participants’ Google account. The

most common permission is modifying Google Play Game

activity (223 instances), followed by viewing primary Google

email address (189), and viewing personal info (177).

Participants were overall only Slightly concerned or Not

concerned about the access granted to third-party apps, but

showed the most concern about apps viewing personal info;

39% were Very concerned, Concerned, or Moderately con-

cerned. Interestingly, such information is perhaps less of a

privacy and security risk than third-party apps that can mod-

ify/view contacts, email, calendar events, or cloud storage.

The relative lack of concern with these permissions could be

attributed to a transference of trust to Google, as evidenced

by open-ended responses where participants indicated that

they believe Google is properly vetting these accesses.

We surveyed participants about the specific apps on their

accounts and asked if they wished to keep or remove account

access for those apps. A logistic regression revealed that par-

ticipants were

5.8×

more likely to want to remove access for

an app when they wished to change which Google account

data the app can access. Additionally, they were

5.9×

more

likely to keep access when the app was recently used, and

6.0×

more likely to keep access when they viewed the app

as beneficial. However, 79% and 78% of participants indi-

cated that they currently Rarely or Never review their apps

and SSOs, respectively. After viewing their third-party ac-

cesses as part of our survey though, the vast majority (95%)

of participants indicated they would want reminders to review

those at least Once a year.

These findings suggest a significant opportunity to improve

how users interact with third parties with programmatic access

to their accounts by helping users to identify and remove less

frequently used apps/SSO in an automated way, or to simply

revoke access after a period of disuse. Similarly, Google

could require regular re-approval of access, perhaps yearly so

as not to be too disruptive. Additionally, many participants

articulated a desire for controls of the permissions for third-

party apps. This would allow users to better limit which

aspects of their Google account each app/SSO can access

with respect to the benefit being provided, rather than forcing

them to accept an all-or-nothing approach.

2

https://myaccount.google.com/permissions

2 Background and Related Work

Russell, et al. [

32

] characterize online APIs as among: content-

focused APIs that provide data; feature APIs that integrate

existing software functionality from elsewhere; unofficial

APIs that (unintentionally) expose internal interfaces; and

analytic APIs that track user experiences. Here, we focus

on Google’s content-focused and feature APIs that enable

third-party developers to register apps with Google that can

perform operations on behalf of a user. Most services, in-

cluding Google’s, use the OAuth standard [

2

] to delegate and

manage these authorizations. OAuth has been the focus of

much security research [

5

,

36

,

45

], and in this paper we do

not investigate the security of OAuth directly but rather user

awareness and concerns for such delegations.

While we primarily focus on third-party apps, we also

consider SSO services as a form of third-party apps with

limited functionality. Bauer et al. [

6

] looked at willingness to

use the SSOs of Google, Facebook and other services, finding

that there were concerns with information sharing through

SSO, despite messaging. We find similar concerns in our

study. Ghasemisharif et al. [

14

] studied SSO with respect to

potential for account hijacking. The authors also measured

the prevalence of SSOs, finding that Facebook is the most

prevalent SSO service, followed by Twitter and Google. Hu

et al. [

21

] investigated SSOs in the context of online social

networks and how apps can complete an impersonation attack.

And Zhou et al. completed automated vulnerability testing

of SSO on the web [

43

]. Here we assume that the SSO is

properly implemented and instead focus on user perceptions

of sharing information with third-parties via SSO services.

Prior work on third-party apps have mostly focused on the

Facebook ecosystem. Felt et al. [

11

] examined 150 Facebook

platform apps in 2008, finding that 90% of the examined apps

have unnecessary access to private data. Huber et al. [

22

] de-

veloped a method to analyze privacy leaks in Facebook apps

at scale by leveraging client-side

iframes

to capture network

traffic. Google third-party apps do not necessarily operate

client-side. More recently, Farooqi et al. [

10

] used “honey-

token” email addresses (i. e., auto-generated accounts on an

email server that the researchers control) to detect Facebook

apps inappropriately collecting and using those addresses.

Such a method could also be used for Google third-party apps

but was not the primary focus of this research.

Our work is also related to prior research on permission

management for online APIs. Similar to Wang et al. [

39

],

who analyzed the permissions requested by Facebook API

apps at install time, we explore the permissions requested by

third-party apps that integrate with Google’s API. Prior work

explored a subset of these permissions on Google [

31

]. A lack

of centralization for third-party apps means there is far from

comprehensive coverage. Our work expands on this effort

with in-the-wild observations of apps authorized on actual

users’ Google accounts.

Permissions have been extensively studied in the context

3398 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

of smartphone apps. Notably, Felt et al. [

12

,

13

] examined

Android apps and found that one-third are overprivileged, and

Wijesekera et al. [

41

] surveyed Android users’ perceptions of

app permissions, 80% of whom wished to deny at least one

permission. With the shift towards runtime, ask-on-first-use

permission requests [

1

,

3

], Wijesekera et al. in 2017 [

42

]

developed a classifier to predict user permission preferences

by taking into account the context of the permission request.

Likewise, Smullen, et al. in 2020 [

35

] built a classifier that

demonstrated users are sensitive to the purpose of particular

permissions requested by apps. Our results show that similar

contextualization has impact on users’ perceptions of per-

missions, and recommend moving towards auto-review and

auto-revocation models for third-party apps as a whole and

for individual permissions.

Finally, this research is also related to work on privacy and

transparency dashboards for online services. These have been

both extensively proposed and explored in the literature [

7

,

9

,

20

,

24

,

26

,

28

,

29

,

33

,

37

,

40

,

44

]. The “Apps with access

to your account” page, to which we direct participants in the

survey, functions similarly to other transparency dashboards;

however, this dashboard offers less functionality than other

dashboards. We explore ways to improve management of

third-party apps through the web interface in Section 5.

3 Method

We begin by describing the two surveys. The first survey

asked participants to recall prior experiences with third-party

apps and SSOs. The second survey leveraged a custom

browser extension and asked participants to respond to the

specific SSOs and third-party apps currently authorized on

their Google account. In the remainder of this section, we

detail our study procedures, describe how we recruited partic-

ipants, discuss ethical considerations of our study, and outline

the limitations of our approach.

First Survey.

Below, the first survey is described. The full

survey can be found in subsection A.1.

1. Informed Consent: Participants consented to the study.

2.

Google Account Use: Participants were asked if they have

a Gmail account (as surrogate for a Google account), if it

is their primary Google account with sole ownership, and

the age of the account. Questions: Q

1

1–Q

1

4.

3.

Familiarity with “Sign in with Google”: Participants were

provided with contextual information from Google’s docu-

mentation [

18

] alongside a screenshot of a “Sign in with

Google” button (taken from Yelp) and asked about their

recent experiences using their Google account to sign into

a third-party app or service. Questions: Q

1

6–Q

1

9.

4.

Familiarity with Third-Party App Account Access: Par-

ticipants were provided with contextual information from

Google’s documentation [

16

] alongside a screenshot of a

third-party app’s Google API authorization screen (taken

from a generic app). Next, participants were asked about

their recent experiences granting a third-party app access

to their Google account. Questions: Q

1

10–Q

1

13.

5.

IUIPC-8: Participants answered the Internet users’ infor-

mation privacy concerns (IUIPC-8) questionnaire [

19

], to

gain insights into participants’ privacy concerns.

6.

Demographics: Participants were asked to provide de-

mographic information, such as age, identified gender,

education, and technical background. Questions: D1–D4.

Second Survey.

The second survey recruited from those

who completed the first survey. We used the following in-

clusion criteria to ensure participants have active Google

accounts with SSOs and/or third-party apps: (i) the partici-

pant has a Gmail account, (ii) the participant uses the Gmail

account as their primary Google account, (iii) the participant

has sole ownership of their Google account, (iv) the partici-

pant has used their Google account for more than one month,

(v) the participant correctly answered the attention checks.

Below, we describe each part of the second survey in detail,

and the full survey can be found in subsection A.2.

1.

Informed Consent: Participants consented to the main

study, which included notice that they would be asked to

install a web browser extension that would access their

Google’s “Apps with access to your account” page.

2.

Extension Installation: Participants installed the browser

extension that locally parses third-party apps and SSOs

and displays specific apps to the participant as part of the

survey. The extension also recorded aggregate information

about the number of SSO and API authorizations and the

date of the oldest and newest authorization.

3.

Explore Apps with Access to Your Account: We provided

participants with a brief descriptive introduction and then

directed them to explore their Google “Apps with access

to your account” page for one minute. This interaction

was managed by the browser extension with an overlay

banner and restricted navigation away from the page.

4.

Account Access Questions: Participants were asked what

they consider before allowing third parties access to their

Google account and services and how often that access is

reviewed. Questions: Q

2

1–Q

2

4.

5.

Keep or Remove: Each participants was shown all their

Google account authorizations and if they wished to keep

or remove the authorization. Question: Q

2

5

6.

App Permissions: Participants were asked about the per-

missions for their newest, oldest, and a random third-party

app to investigate potential impacts of installation time on

concern, benefit, and recall. Questions: Q

2

7–Q

2

14.

7.

Reflections: Participants were asked to reflect on their

understanding of the Google “Apps with access to your

account” page and if they would change their behavior as

a result of that interaction. Questions Q

2

15– Q

2

20.

8.

Feature Improvements: Participants provided suggestions

for improving Google’s “Apps with access to your account”

page. Questions Q

2

21–Q

2

26.

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3399

Table 1: Demographic and IUIPC data collected at the end

of the first survey.

First Second

Survey Survey

(n = 432) (n = 214)

Gender

n % n %

Woman 204 47 99 46

Man 216 50 107 50

Non-binary 11 3 7 3

No answer 1 0 1 1

Age

18–24 132 31 66 31

25–34 157 36 80 37

35–44 75 17 32 15

45–54 44 10 20 9

55+ 23 6 15 7

No answer 1 0 1 1

IUIPC

Avg. SD Avg. SD

Control 5.9 1.0 5.8 1.0

Awareness 6.6 0.7 6.6 0.8

Collection 5.4 1.2 5.3 1.2

IUIPC Combined 5.8 0.8 5.8 0.8

9.

Uninstall Extension: Upon completing the survey, partici-

pants were instructed to remove the browser extension.

Recruitment and Demographics.

We recruited

432

partic-

ipants via Prolific

3

for the first survey between March 31,

2021 and April 20, 2021. After applying our inclusion crite-

ria,

399

participants qualified for the second study, and

214

returned to complete the second survey. Participants received

$1.00 USD

and

$3.00 USD

for completing the first and sec-

ond survey, respectively, and it took, on average,

8

minutes

and 13 minutes to complete, respectively.

Thirty-one percent of first survey participants were between

18

–

24

years old,

36 %

were between

25

–

34

years old, and

33 %

were

35

years or older. The identified gender distribu-

tion for the first survey was

50 %

men,

47 %

women, and

3 %

non-binary, self-described, or choose not disclose gender.

Thirty-one percent of second survey participants were be-

tween

18

–

24

years old,

37 %

were between

25

–

34

years old,

31 %

were

35

years or older, and

1 %

chose not to disclose

their age. The identified gender distribution for the second

survey was

50 %

men,

46 %

women, and

4 %

non-binary,

self-described, or choose not disclose gender. Participant

characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Analysis methods.

When performing quantitative analysis,

descriptive or statistical tests, the analysis is provided in con-

text. For qualitative responses, we use open coding to analyze

responses to open-text questions. First, a primary coder from

the research team crafted a codebook and identified descrip-

tive themes for each question. A secondary coder coded

a

20 %

sub-sample as a consistency check, providing feed-

back on the codebook and iterating with the primary coder

3

https://www.prolific.co

- Prolific participant recruitment service,

as of October 5, 2021.

until inter-coder agreement was reached (Cohen’s

κ > 0.7

,

mean = 0.81, sd = 0.05).

Ethical Considerations.

The study protocol was approved

by The George Washington University Institutional Review

Board (IRB) with approval number

NCR202914

, and through-

out the process we considered the sensitivity of participants’

Google app authorization data at every step. All aspects of

the survey requiring access to the actual Google “Apps with

access to your account” page was administered locally on

the participant’s machine using the browser extension. All

participants were informed about the nature of the study prior

to participating and consented to participating in both surveys.

At no time did the extension or the researchers have access

the participants’ Google password or to any other Google

account data, and all collected data is associated with random

identifiers.

Limitations.

As an online survey, we are limited in that we

cannot probe deeply with follow-up questions to understand

the full range of responses. We attempt to compensate for

this limitation by performing thematic coding across many

responses to capture general opinions and feelings when in-

teracting with third-party apps and SSOs that have access to

their Google account.

Additionally, we are limited in our recruitment sample,

which is generally younger than the population as a whole.

Yet, we argue that despite this limitation, our results offer

insights into user awareness of third-party apps and SSO

access to their Google account, as well as other online services

with third-party APIs. We note that prior work by Redmiles,

et al. [

30

] suggests online studies about privacy and security

behavior can still approximate behaviors of populations.

Some results may be affected by social desirability bias,

where participants might indicate behavior that they believe

we (the researchers) expect them to embody. For example,

this may lead to participants over describing their awareness

or recall of granting access to third-party apps or SSOs, or

their intention to remove access. In these cases, one may view

these results as a potential upper bound on true behavior.

Finally, we acknowledge our study only considers Google,

even though many online services offer APIs. Still, we believe

our findings are broadly applicable because of the consistency

of the underlying mechanisms (i.e. OAuth scopes) and user

consent flows (i.e., users grant install-time permissions with

a dashboard for review) across many major providers.

4 Results

In this section we present the results of the two surveys. We

first describe the observed apps, SSOs, and their permissions

for participants completing the second survey. Next, we ex-

plore participants’ awareness and understanding of third-party

apps and their permissions. We then offer results on partic-

ipants’ motivations to install or not install a third-party app

and their intentions to change settings. Finally, we report

3400 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

38631

22583120

Do you recall ever granting a thrid−party app access to your

Google Account?

Do you recall ever using your Google Account to sign in to third−

party apps or services?

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

No Unsure Yes

Figure 1: Ninety percent of participants recall using their

Google Account to sign in (

Q

1

6

) and over half recall granting

a third-party app access to their Google Account (Q

1

10).

on participants’ reflections on their third-party apps and de-

sired features for improving transparency and control over

API access to their Google account.

4.1 Measurements

Third-party app and SSO findings.

In the first survey, 432

participants self reported if they recalled using Google’s SSO

(

Q

1

6

) or granting third-party apps (

Q

1

10

) access to their

Google account. We found that 89% (

n = 386

) of partici-

pants recalled using SSO to sign into a third-party service.

Furthermore, 52% (

n = 225

) recalled granting a third-party

app access to their Google accounts. See Figure 1.

Additionally, during the first survey, we asked participants

to recall the latest app or service they signed into using their

Google account (

Q

1

7

), and classified their responses into

various categories based on the app or service. We searched

repositories of available third-party apps, e.g., Google Play

or Google Workspace Marketplace, to determine the proper

app category. The top categories include shopping (

n = 51

;

12%), social media (

n = 42

; 10%), gaming (

n = 38

; 9%),

food (n = 34; 8%) and entertainment (n = 28; 6%).

Among the 214 second survey participants, a majority

(

n = 184

; 86%) have at least one SSO linked to their Google

account and 67% (n = 143) have at least one third-party app

with Google account access. Via the custom browser exten-

sion installed by the participants, we observed a total of 1,010

unique SSOs and 455 unique third-party apps accessing par-

ticipants’ Google accounts. For those who have at least one

SSO (

n = 184

), the average number of SSOs per participant

is 13 (median = 9.5; sd = 12). In comparison, those who have

at least one third-party app (

n = 143

) have an average number

of six third-party apps per participant (median = 3; sd = 6.7).

Third-party apps were authorized to access participants’

Google accounts for an average of 285 days (median = 142; sd

= 375). The maximum number of days authorized was 2,519

days and the minimum was one day. The highest number

of SSOs linked to a single participant’s Google account is

35 17 65

30 11 76

23 8 86

newest

Keep App

Aware Perm.

Recall Auth.

28 7 108

35 12 96

18 9 116

oldest

Keep App

Aware Perm.

Recall Auth.

23 11 51

19 9 57

12 6 67

random

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Keep App

Aware Perm.

Recall Auth.

No Unsure Yes

Figure 2: Full results of questions (

Q

2

5

), (

Q

2

7

), and (

Q

2

9

).

Most participants recall authorizing their apps and are aware

that their apps had permissions to access parts of their Google

account. Their newest app is the mostly likely to be removed.

65, and one participant had 49 third-party apps, the most

observed.

Associated account access permissions.

Among the 1,010

distinct SSOs, we recorded 114 unique associated permis-

sions. Moreover, we cataloged 144 unique permissions re-

quested across the 455 distinct third-party apps. The average

number of permissions per SSO was three (median = 2; sd =

1.5); per third-party app, the average number of permissions

was three (median = 2; sd = 2.2).

The third-party app with the greatest number of permis-

sions was Health Sync with 19 permissions. Health Sync was

followed by: autoCrat (14), FitToFit (14), DocuSign GSuite

Add-on (13), Zero - Simple Fasting Tracker (13), and Yahoo!

(12). Only a few ( 1%;

n = 12

) SSOs ask for a single permis-

sion, while 36% (

n = 166

) of third-party apps have only one

permission. Additionally, 78% (

n = 792

) of SSOs have two

or fewer permissions while 56% (

n = 255

) of third-party apps

have two or fewer permissions.

The most common observed permission was “Create, edit,

and delete your Google Play Games activity” (

n = 223

). This

was followed by: “See your primary Google Account email

address” (

n = 189

), “See your personal info, including any

personal info you’ve made publicly available” (

n = 177

),

“See, create, and delete its own configuration data in your

Google Drive” (

n = 71

), and “Associate you with your per-

sonal info on Google” (n = 44).

4.2 Awareness and Understanding

Awareness of Third-party Apps and SSOs.

In the second

survey, we used the browser extension to show participants

their newest, oldest, and a random third-party app. For partic-

ipants with only two apps, we considered those apps as their

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3401

oldest and newest. And for participants with only one app, we

considered it as their oldest. This results in imbalanced partic-

ipants with oldest apps

n

old

= 143

, newest apps

n

new

= 117

,

and random apps n

rand

= 85.

Participants were first asked if they recalled authorizing

each app (

Q

2

7

). Among participants with at least one app,

33 %

(

n = 47

) could not recall authorizing at least one of

them. The oldest installed app was recalled the most often

81 %

(

n = 116

), followed by the randomly selected app at

79 %

(

n = 67

), and finally the newest app at

74 %

(

n = 86

).

There were no significant differences between the apps shown

with respect to positive recall compared to negative or unsure

responses (

χ

2

= 0.27, p = 0.87

). (See Figure 3 displays the

full details.)

When asked when they last used these apps (

Q

2

8

); over half

(51%;

n = 74

) of the participants reported using their oldest

app Today or In the previous week. Whereas 43% (

n = 50

)

report using their newest app, and only 34% (

n = 29

) report

using their random app, over that same time period. There

were no statistical differences (using a Kruskal-Wallace test

H = 2.15, p = 0.34

) between reported last use of apps when

comparing newest, oldest, and random apps.

Subsequently, we asked participants if prior to seeing the

details about their newest, oldest, and a randomly chosen app

in the survey, they were aware that the app had permissions to

access their Google account data (

Q

2

9

). Forty-nine percent

(

n = 70

) of participants with third-party apps were not aware,

for at least one of those apps, that the app had permissions

to access parts of their Google account data. Participants

were more likely to be unaware of the Google account access

permissions of their newest app (35%;

n = 41

), followed by

their oldest app (33%;

n = 47

), and random app (33%;

n = 28

).

Again, though, there were no significant differences between

awareness of the apps (

χ

2

= 0.032, p = 0.98

). Figure 2 shows

the full results of app recall and awareness.

In the first survey, when participants were asked if they

recalled using Google’s SSO (

Q

1

6

), 10% (

n = 42

) responded

No or Unsure. Yet, 16 of the 19 (84%) of those same partici-

pants who completed the second survey actually did have a

SSO linked with their Google account. We also asked whether

they recalled granting a third party access to their Google ac-

count (

Q

1

10

), and 47% (

n = 203

) answered No or Unsure.

However, 52 of 95 (55%) of those very same participants who

completed the second survey in fact had granted a third-party

app access to their account.

Benefits From and Concerns For Third-Party Apps.

Par-

ticipants selected on a 5-point Likert agreement scale to indi-

cate the benefits of their newest, oldest and randomly picked

apps (

Q

2

10

). Eighty-two percent (

n = 117

) of participants

with apps Agree or Strongly agree that at least one of their

third-party apps is beneficial. The oldest app was reported as

the most beneficial with 59% (

n = 84

) who Agree or Strongly

agree, followed by 54% (

n = 63

) for the newest app, and 51%

25 25 23 21 21

Newest

App

When was the last time you recall using...

42 32 22 19 14 14

Oldest

App

20 9 14 23 6 13

Random

App

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Today Previous week Previous month

Previous year More than a year Unsure

Figure 3: Participants’ oldest app was also their most recently

used as over half report using their oldest app Today or In the

previous week (Q

2

8).

(

n = 43

) for the random app. However, there were no signifi-

cant differences across responses based on a Kruskal-Wallace

test (H = 2.12, p = 0.34).

Additionally, participants were asked whether they were

concerned about their newest, oldest and random apps having

access to their Google accounts (

Q

2

10

). Fifty percent (

n = 71

)

of participants with apps Agree or Strongly agree that they

were concerned with at least one of their third-party apps that

can access their Google account. Of the participants who

were concerned, 28% (

n = 24

) Agree or Strongly agree to

being concerned with their random app, 22% (

n = 26

) with

their newest, and 22% (

n = 32

) with their oldest. The full

results for app benefit and concern are shown in Figure 4,

and again, there were no statistically significant differences

(H = 1.58, p = 0.45).

Understanding App Access Permissions.

We asked partic-

ipants who have apps to rate their confidence in understanding

the permissions held by their third-party apps (

Q

2

11

). Note

that each participant had their own set of apps and permis-

sions, so there is an imbalance in the number of participants

surveyed for a given permission. Thus, we present permission-

specific results as percentages, with full counts in the figures.

Thirty-one percent (

n = 45

) of participants had at least one

permission that they were Not confident that they understood.

For the six most prevalent permissions requested by apps

in our study, participants were Confident or Very confident

(over

50 %

) in understanding each of them. Participants were

the most confident in understanding the permission “See your

primary Google Account email address,” with

33 %

Confident

and

39 %

Very confident. This was also the most common

permission surveyed, with 223 occurrences in third-party

apps. Conversely, participants were least confident in their

understanding of the permission “See your personal info, in-

3402 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

20 13 21 34 29

20

40 21 25 11

25

44 22 21 5

newest

Beneficial

Change

Concerned

14 19 26 53 31

17

61 33 22 10

17

60 34 25 7

oldest

Beneficial

Change

Concerned

14 12 16 29 14

14

29 16 13 13

20

29 12 16 8

random

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Beneficial

Change

Concerned

Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree n...

Agree Strongly agree

Figure 4: Full results of question (

Q

2

10

). Most participants

are not concerned about their third-party apps having access

to their Google account. Over half of participants do not want

to change the parts of their Google account that an app can

access. A majority of participants agree that app access to

their Google account is beneficial.

cluding any personal info you’ve made publicly available,”

with

12 %

Not confident,

16 %

Slightly confident. There is

also evidence in the qualitative data where a participants note

that this permission is confusing because it does not suffi-

ciently detail what information is included in “personal info.”

This was the second most common permission surveyed, with

186 occurrences in third-party apps. Results for the top six

most prevalent permissions can be found in Figure 5. Statis-

tical comparisons were not performed due to the imbalance

between groups for which permissions were surveyed.

Necessity of Access Permissions.

We asked participants to

report the necessity of each permission on a 5-point Likert

scale for their newest, oldest and randomly selected third party

app (

Q

2

12

). Sixty-one percent (

n = 87

) of participants had at

least one permission that they reported was Not necessary.

Among the six most prevalent permissions, participants

found the permission “See your personal info, including any

personal info you’ve made publicly available” to be the most

unnecessary, with 30% who stated that it is Not necessary and

31% who said it is only Slightly necessary. This is followed

by the permission “See, edit, download, and permanently

delete your contacts” in which 26% said it was Not necessary

and 18% said it is only Slightly necessary. At least 50% of

participants found the remaining prevalent permissions either

Necessary or Very necessary. Participants rated functional

permissions, such as “Read, compose, send, and permanently

delete all your email from Gmail,” to be more necessary for

the app to benefit them than data access permissions, like “See

your personal info, including any personal info you’ve made

publicly available.” The top six most prevalent permission

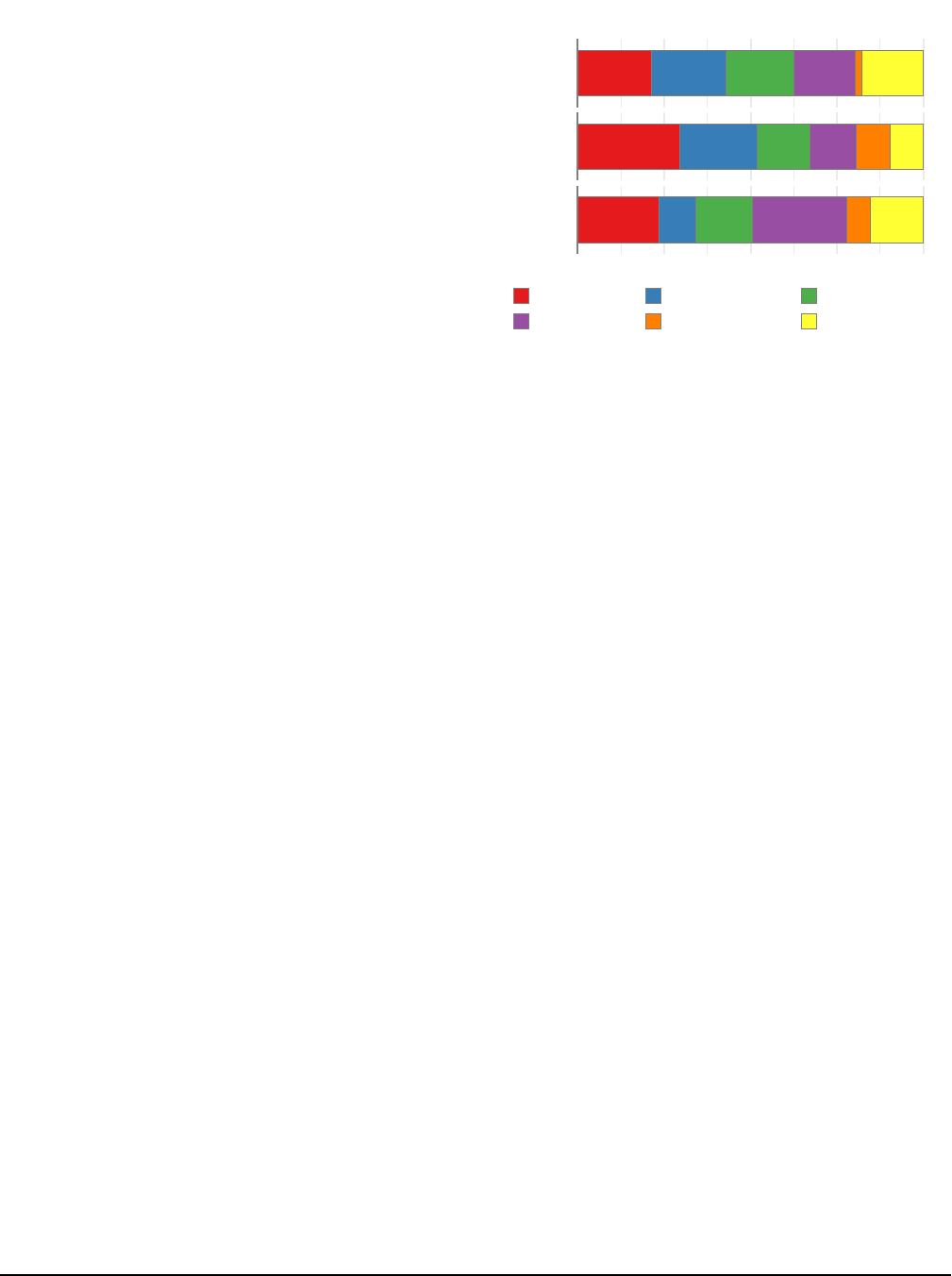

23 29 41 52 41

View

Personal

Info

How confident are you that you understand what

each permission allows the app to do?

7 6 13 19 21

Modify

Gmail

6 4 14 18 19

Modify

Contacts

6 4 8 21 18

Modify

Google Play

3 6 7 15 19

Modify

Google

Calendar

20 12 32 73 86

View Gmail

Address

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Not confident Slightly confident Moderately conf...

Confident Very confident

Figure 5: Results for (

Q

2

11

) for the top six most prevalent

permissions, of which “View Personal Info” was the least

understood and “View Gmail Address” was the most.

results for necessity can be found in Figure 6, and again, sta-

tistical comparisons were not performed due to the imbalance

between groups for which permissions were surveyed.

Concern for Access Permissions.

In

Q

2

13

we asked the

level of concern participants have about third-party apps ac-

cessing their account through various permissions. Forty-six

percent (

n = 66

) of participants had at least one permission

that they were either Concerned or Very concerned about.

For five of the six most prevalent permissions requested by

third-party apps observed in our study, over 70% of partic-

ipants answered Not concerned or only Slightly concerned

about apps on their account having these permissions. The

permission “See your personal info, including any personal

info you’ve made publicly available” had the highest concern,

with 16 % Concerned, 5 % Very concerned. (See Figure 7.)

Reasons for Concern.

Participants also provided free re-

sponses describing any concerns they have with a third-party

app, either the newest, oldest, or randomly chosen, having

these access permissions (

Q

2

14

). Qualitative coding of the

responses revealed that some participants expressed concern

with the permissions held by their apps (newest,

n = 46

; old-

est,

n = 90

; random,

n = 33

). The most common reasons

for concern were access to personal or sensitive information,

unnecessary access, ability to delete, and access to contacts

and email. For example, P53 shared, “I don’t want them hav-

ing access to my personal information” (newest; YouTube on

Xbox Live). Examples of concern regarding unnecessary ac-

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3403

56 57 42 24 7

View

Personal

Info

How necessary do you think each permission is for

the app to function in a way that benefits you?

16 11 11 9 14

Modify

Contacts

13 11 5 18 10

Modify

Google Play

7 9 9 12 13

Modify

Google

Calendar

31 25 54 72 41

View Gmail

Address

8 6 11 15 26

Modify

Gmail

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Not necessary Slightly necessary Moderately nece...

Necessary Very necessary

Figure 6: Results for (

Q

2

12

) for the top six most prevalent

permissions, of which “View Personal Info” was considered

the least necessary and “Modify Gmail” was the most.

count access include: “I’m a bit concerned about their access

to my Youtube Channel, since it seems a bit unnecessary and

excessive” (P170; newest; PlayStation Network) and “Not

sure why it needs Google Drive access, it shouldn’t be cre-

ating anything in there” (P93; random; Idle Island: Build

and Survive). Permissions that include the ability to delete

files was often concerning, for instance, “I don’t know if I

want them to be able to delete stuff from my Google Drive”

(P142; newest; CloudConvert). Access to email and contacts

were common concerns; for instance, P63 said, “As with any

app that requires having access to send emails, I’m always

worried about something unauthorized being sent” (oldest;

Boomerang for Gmail). P61 (oldest; Quora) noted:

I didn’t know that they could see and download my con-

tacts. That is a bit concerning because I don’t know what

they do with that data.

Participants were also concerned when they could not recall

authorizing the access, e.g., “I don’t remember authorizing

this app to have access to my Google account” (P10, newest;

Email - Edison Mail). Additionally, when participants infre-

quently used an app but found out it still had access to their

account, e.g., “I don’t use it anymore and they still have ac-

cess to my photos” (P16; random; Chatbooks - Print Family

Photos) and “I don’t use the Google nest hub anymore, so

it shouldn’t have access to my full account” (P12; oldest;

Google Nest Hub). A number of participants complained that

they had deleted the app from their device but it still had ac-

cess to their accounts, as when P137 shared, “I have removed

9 29 35 65 48

View

Personal

Info

How concerned are you about the app accessing

your account using these permissions?

3 6 8 19 25

Modify

Contacts

3 5 9 18 31

Modify

Gmail

2 6 4 10 35

Modify

Google Play

12 25 41 140

View Gmail

Address

2 5 14 28

Modify

Google

Calendar

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Very concerned Concerned Moderately conc...

Slightly concerned Not concerned

Figure 7: Results for (

Q

2

13

) for the top six most prevalent

permissions, of which “View Personal Info” was the most

concerning and “Modify Google Calendar” was the least.

the app from my phone and I don’t see why the app still has

to have these permissions” (newest; Adidas Training), and

P26 noted, “I was unaware these permissions were still on the

app as I’ve deleted the app” (newest; Linkt).

Many participants stated that they were unconcerned by the

app permissions (newest,

n = 62

; oldest,

n = 44

; random,

n =

41

). The most common reasons for the lack of concern was the

necessity of the permissions, and the limited access that the

permissions provided. For instance, P131 said “I don’t think

it has too many permissions and nothing seems unreasonable,

so I’m okay with this” (random; Lumin PDF), and P158

stated “It is a game and both of the permissions are valid”

(random; Starlost - Space Shooter). Some were unconcerned

because they trust the app, e.g., “I trust the service to keep

my information secure” (P148; newest; Amazing Marvin).

For others, the trust originates with the company who makes

the app, e.g., “I’ve never worried about Apple invading my

privacy” (P189; random; macOS).

4.3 Granting and Reviewing Account Access

Considerations When Granting App/SSO Access.

Google’s documentation [

15

] advises that users consider the

following five factors before granting a third-party access

to their Google account: (i) security, (ii) data use, (iii) data

deletion, (iv) policy changes, and (v) data visibility.

On a five-point agreement Likert-scale, we asked the par-

ticipants with apps if they considered these factors before

granting a third-party app access to their Google account

3404 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

6 37 53 65 23

5

30 44 69 36

19 29 81 52

16 23 91 51

14 16 108 45

SSO

Will Tell Change

Whether Delete

Who Sees Data

How Data Used

How Secure

6 10 23 60 47

9

34 35 49 19

6

30 32 55 23

7

15 23 65 36

4

13 18 73 38

12 15 82 36

APP

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

What Access

Will Tell Change

Whether Delete

Who Sees Data

How Data Used

How Secure

Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree n...

Agree Strongly agree

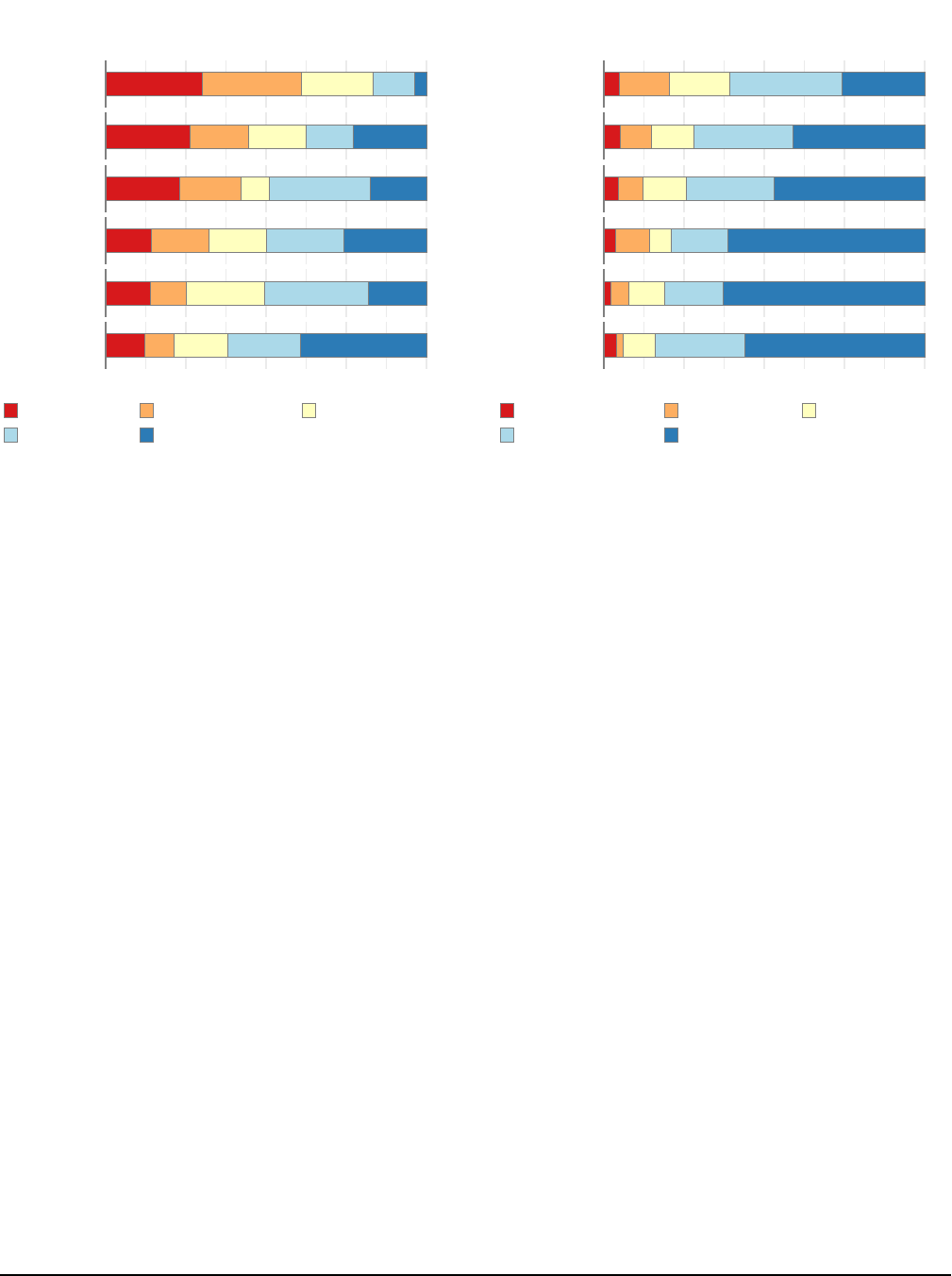

Figure 8: Full results of questions (

Q

2

1

) and (

Q

2

3

) in which

participants are asked what they consider before granting

Google account access to a third-party APP or SSO.

(

Q

2

3

) and before using their Google account to sign into a

service via SSO (

Q

2

1

); those results are presented in Figure 8.

The most considered factor for third-party apps was the

security of the app or website (security), in which

83 %

(

n =

118

) Agree or Strongly Agree. The next factor was how the

app or website will use your data (data use) where

78 %

(

n =

111

) Agree or Strongly Agree. This was followed by who else

can see your data on the app or website (data visibility), in

which

71 %

(

n = 101

) Agree or Strongly Agree. Next was

whether you can delete your data from the app or website

(data deletion), where

55 %

(

n = 78

) either Agree or Strongly

Agree. The least considered factor was whether the app or

website will tell you if something changes (policy changes),

where fewer than half (

n = 68

;

48 %

) Agree or Strongly Agree.

Among participants with SSOs (

n = 184

), the data shows

they considered similar factors as those for third-party app

account access. Again, the most considered factor was how

secure is the app or website (security), in which

83 %

(

n =

153

) Agree or Strongly Agree. The next most considered

factor was how the app or website will use your data (data

use) where

77 %

(

n = 142

) Agree or Strongly Agree. This was

followed by who else can see your data on the app or website

(data visibility), in which

72 %

(

n = 133

) Agree or Strongly

Agree. Next was whether you can delete your data from the

app or website (data deletion), where

57 %

(

n = 105

) either

Agree or Strongly Agree. The least considered factor was

whether the app or website will tell you if something changes

(policy changes), where fewer than half (

n = 88

;

48 %

) Agree

or Strongly Agree.

We used a Mann-Whitney U-test to compare each of the

considerations, comparing SSO to third-party access (see top

of Figure 8). We did not find any significant differences,

suggesting that participants view SSOs and third-party apps

accessing their Google accounts in similar ways when deter-

mining if they should grant that access. More detail on SSO

considerations is in the next section.

In open-response questions, we asked participants to pro-

vide more details on what they consider before granting

a third-party app access to their Google account or use

SSOs (

Q

1

12

,

Q

1

13

). Participants often (Q12,

n = 42

; Q13,

n = 43

) responded that they consider what permissions the

third-party would obtain, e.g., “What capabilities I was giving

the third-party” (P362). Security (Q12,

n = 33

; Q13,

n = 23

)

and privacy (Q12,

n = 22

; Q13,

n = 28

) were common con-

siderations. For instance P160 noted, “Whether it was secure

and could I trust it,” and P283 added, “I’m always worried

about my privacy anytime a app [sic] asks me for that infor-

mation.” Still, many participants (Q12,

n = 31

; Q13,

n = 10

)

had no considerations. For instance, P24 shared, “It was a

pop up so I didn’t consider it much at all.”

One particularly interesting theme that emerged from open

coding was the transfer of trust from the Google brand name

to third-party apps and SSOs when participants considered

granting access (Q12,

n = 7

; Q13,

n = 4

). That is, participants

were more likely to trust a third-party service because it was

using Google, and they trusted Google, irrespective of the

nature of the third-party service. For example, P278 declared,

“That it was okay since Google was allowing it,” and P297

added, “It must be okay since it partnered with Google.” P117

provided another example:

I would consider nothing again, I probably put too much

trust in Google and it’s become a crutch at this point, I

would easily allow it to be used in 3rd party situations.

and P161:

Nothing! Like before, I generally trust anything that

leads to that Google SSO page.

When considering granting SSO access (

Q

1

8

), many partic-

ipants (

n = 55

) considered ease of use and convenience before

signing in, and a common theme was the ease of reusing their

Google account login credentials versus creating a new ac-

count on a third-party app or website, e.g., “It is easier and

more convenient than making a brand new account to some

third party website” (P21). There were also many (

n = 42

)

who were unconcerned and had few considerations, such as

P99 who said,“I didn’t consider much, I use Google sign in

pretty regularly,” and P117 who stated, “I didn’t consider

much, my Google account has always been good to me and

offered ease of use with many things.”

Participants (

n = 27

) also shared concerns such as what

information would be accessible to the third-party app or ser-

vice; for instance, P90 responded, “If that service has access

to information associated with my Google Account,” and P91

replied, “I considered what that app would have access to

if I signed in through there.” Security (

n = 29

) and privacy

(

n = 13

) were common considerations. For example P80

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3405

37 106 9 16 13

How often do you review what services you can sign into using

your Google account?

35 80 16 10

How often do you review what services have access to your Google

account?

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Never Rarely Daily

Weekly Monthly Yearly

Figure 9: Over

75 %

of participants stated that they Never or

Rarely review what services they can sign into using (

Q

2

2

) or

have access to their Google account (Q

2

4).

shared, “I was worried about security of my Google Account,”

and P271 added, “The private data that this application was

going to read, in other words, I worry about my privacy.”

Some participants (

n = 12

) described a trade-off between

information sharing and convenience. For instance, P16

shared, “The effort of making a new account versus shar-

ing my google info.” Trust of the website or service being

signed into is also a common theme (

n = 26

), e.g., “I consider

if the website is trustworthy and if I can trust signing in using

my Gmail account in their website” (P68).

Reasons For Authorizing Account Access.

We asked par-

ticipants what was the purpose of allowing third-party ac-

cess (

Q

1

11

). The purpose for many (

n = 45

) participants was

the utility that the app provided, such as email and contact

management, file transfer, and synchronizing data between

devices. For instance, P37 explained, “I gave a ringtone app

access to my contacts and messages so that it can change the

notification/ringtone sounds” and P210 shared that the apps

purpose was “Allowing me access to multiple e-mails from

the same app on my Windows computer.” Another popular

(

n = 38

) purpose was calendar management, e.g., “Zoom, to

allow it to add meetings to my calendar” P25. Gaming was a

common (n = 38) purpose. For example, P355 responded:

I allowed access to my Google account for a lot of games,

because I can get achievements to be displayed on my

account with Google, and also it is usually an easy way

to recover or save data between devices.

Some participants (

n = 15

) just could not recall the purpose,

like P404 who shared, “I don’t really remember but I do

remember encountering this type of screen in the past.”

User Review of Apps With Account Access.

We find that

participants rarely or never review the services they can sign

into using their Google account or the apps that have access

to their Google account. We asked participants how often

they review the services they can sign into using their Google

account (

Q

2

2

). A majority (

n = 106

;

58 %

) Rarely review

their services,

20 %

(

n = 37

) Never review, and

16 %

(

n = 29

)

review them Monthly or Yearly. Among participants with

apps, we also asked how often they review the services that

have access to their Google account (

Q

2

4

). Again, a majority

(

n = 80

;

56 %

) Rarely review their services,

24 %

(

n = 35

)

Never review, and

18 %

(

n = 26

) review them Monthly or

Yearly. Figure 9 shows the full results of these questions.

For each of their newest, oldest and random app, we also

asked participants if they would like to change which parts

of their Google account that the third-party app can access

(

Q

2

10

).

52 %

(

n = 74

) of participants Agree or Strongly agree

they want to change which parts of their Google account are

accessible for at least one of their apps. The most agreement

for changing access was for the random app, in which 30%

indicated they Agree (15%;

n = 13

) or even Strongly agree

(15%;

n = 13

). This was followed by the newest app, where

21% (

n = 25

) Agree and 9% (

n = 11

) Strongly agree. The

oldest app had the least agreement for a change in access with

only 15% (n = 22) Agree and 7% (n = 10) Strongly agree.

Keeping or Removing Apps.

For each of the specific apps

shown—newest, oldest, and randomly chosen—we asked

participant if they would like to keep or remove the app or are

unsure about what to do (

Q

2

5

).

43 %

(

n = 62

) of participants

with third-party apps wanted to remove at least one of those

apps. Due to private data aggregation during the survey,

we only linked the keep/remove preferences for the newest,

oldest, and random app that were specifically reviewed by

the participants. For their newest app,

56 %

(

n = 65

) of the

participants said they want to keep it,

30 %

(

n = 35

) chose

to remove, and

15 %

(

n = 17

) answered unsure. Many more

participants (

76 %

;

n = 108

) responded to keep their oldest

app. While

20 %

(

n = 28

) wanted to remove, and

5 %

(

n =

7

) were unsure.

60 %

(

n = 51

) of participants wanted to

keep their randomly selected app, 27% (

n = 23

) answered to

remove, and 13% (n =

11

) were unsure. However, a Kruskal-

Wallace test found no significant differences between the three

apps shown (H = 0.49, p = 0.77). Full results in Figure 2.

We performed logistic regression to determine factors that

would lead a participant to remove a third-party app access

from their Google account (see Table 2). We controlled for

repeated measures by adding random intercepts to the model,

as each participant provided up to three apps they wished

to keep or remove. We found a significant correlation with

participants who want to change which parts of their Google

account the app can access (

β = 1.75, OR = 5.76, p = 0.001

),

where those participants were

5.8×

more likely to want to

remove the app access. We found a significant correlation

with participants who have used the app within the last month

(

β = −1.76, OR = 0.17, p =< 0.001

), and those participants

3406 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

Table 2: Binomial logistic model to describe which factors in-

fluenced the preference to remove an app (Remove responses

to question Q

2

5). The Aldrich-Nelson pseudo R

2

= 0.52.

Factor Est. OR Error Pr(>|z|)

(Intercept) −1.02 0.36 0.68 0.134

Participant’s newest app 0.22 1.24 0.53 0.687

Participant’s oldest app −0.07 0.93 0.56 0.904

Recall = Yes 0.92 2.50 0.68 0.179

Aware app permissions = Yes −1.15 0.32 0.61 0.058 .

Last use ∈ {day, week, month} −1.76 0.17 0.49 <0.001 ***

Access benef. ∈ {Agr., Str. Ag.} −1.80 0.17 0.55 0.001 **

Access conc. ∈ {Agr., Str. Ag.} 0.43 1.53 0.56 0.443

Access change ∈ {Agr., Str. Ag.} 1.75 5.76 0.54 0.001 **

# of permissions > median 0.05 1.05 0.44 0.909

Time since install < 3 months 0.84 2.32 0.54 0.123

Time since install > 2 years 0.26 1.30 0.66 0.689

Signif. codes: *** b= < 0.001; ** b= < 0.01; * b= < 0.05; · b= < 0.1

are

5.9×

more likely to want to keep the app access. We

also found significant correlation with participants who found

the app beneficial (

β = −1.80, OR = 0.17, p = 0.001

), where

they too are

5.9×

more likely to want to keep the app access.

These findings suggest the importance of app usage frequency

in account access authorization.

4.4 Reflection and Features

Understanding Account Linking and Access.

We directed

all participants in the second survey (

n = 214

) to explore

their “Apps with access to your account” page. We then

asked whether the page helps them to better understand which

third-party apps and websites are linked to their Google ac-

count (Q

2

15); nearly all participants (n = 204; 95 %) agreed

that it help. And when asked if the page helps to better un-

derstand which parts of their Google account third-party apps

can access (

Q

2

16

), again nearly all participants (

n = 198

;

93 %

) agreed. This suggests that the management page has

the potential for being an important tool.

Change Settings and Review Apps.

We asked participants

to indicate whether they intend to change any settings after

seeing their “Apps with access to your account” page (

Q

2

17

),

and roughly half (

n = 105

) affirmed that they would change

settings. Over

70 %

(

n = 152

) indicated they plan to review

third-party apps in six months (

Q

2

18

). Refer to Figure 10 to

see the full results of these questions.

If a participant affirmed they would change a setting, we

asked them to tell us which settings they would change

(

Q

2

19

). Many participants (

n = 76

) wanted to remove ac-

cess from one or more apps. They often (

n = 41

) mentioned

unused apps; for instance, P23 said:

I would definitely remove many of the apps that I do not

use anymore. They absolutely do not need to be linked

to my Google account anymore.

1054960

1523923

In six months do you see yourself reviewing third−party apps from

your "Apps with access to your account" page?

After completing this survey, do you see yourself changing any

settings on your "Apps with access to your account" page?

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

No Unsure Yes

Figure 10: Roughly

50 %

of participants stated that they

would change their settings after the survey (

Q

2

17

), and a

majority would review third-party apps in six months (

Q

2

18

).

Participants also wished to remove apps they no longer re-

called authorizing, e.g., “There are apps I do not use and do

not recall allowing access to my Google account” (P24).

Some participants (

n = 27

) wanted to change specific per-

missions access, something not allowable with the current

interface. The most common permissions mentioned included

contacts, account info, delete or modify files, and “unneces-

sary permissions.” For example, P189 said, “I would remove

Dropbox’s access to my contacts,” and P192 noted, “. . . and

maybe restrict Streak’s access to my Google Drive.” Partici-

pants (

n = 8

) mentioned protecting their personal information

as a reason for the settings change, e.g., “I would limit the

amount of information different apps can view - especially

with my personal information” (P145).

If a participant affirmed they planned to review third-party

apps in six months, we asked them to tell us what they would

look for (

Q

2

20

). Many participants (

n = 43

) would look for

apps that they no longer use, such as P137, who replied “I

would look for apps that I no longer use and if they still have

access to my account and to what parts of my account.” Some

participants (

n = 22

) said they would look for new apps that

have access to their account, e.g., “If any new apps are listed

that I don’t remember approving” (P169). Others (

n = 22

)

wanted to review changes to the list of apps with access to

their Google account. For instance, P138 explained:

I would look for any unexpected or new third parties and

just make sure that all of them have very limited access to

my personal information. I’d maybe continue to review

this page over time to make sure nothing has changed.

Some wanted to review changes to the existing apps, like

P180 who shared, “Check to see if anything has changed like

they got more access without saying anything.” Participants

(

n = 8

) also wanted to review how much access was allowed

USENIX Association 31st USENIX Security Symposium 3407

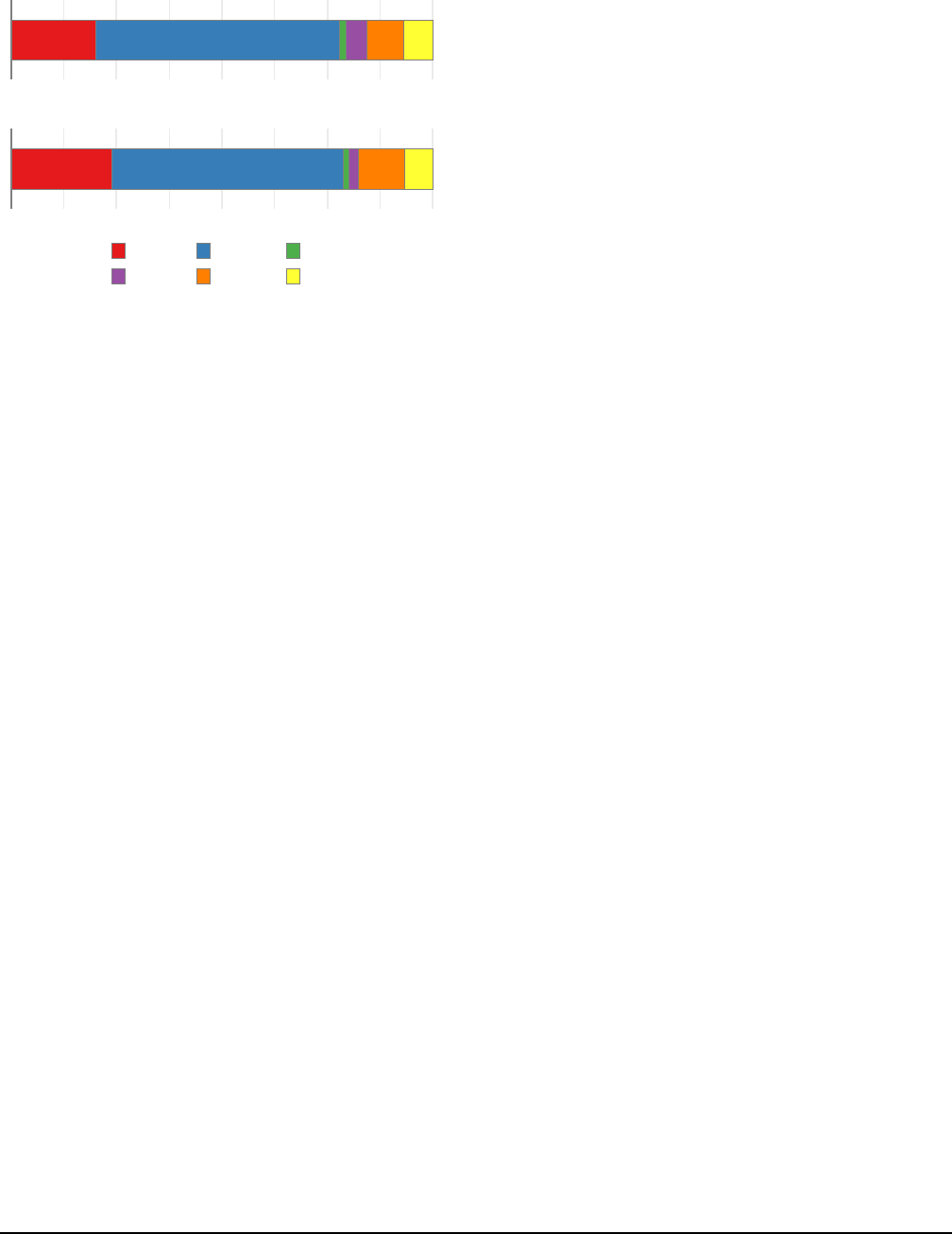

79 117

127 63

Reapprove

Reminder

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Once every three years Once a year Once a month

Once a week Not at all

Figure 11: A majority of participants stated that they wanted

an email reminder to review their “Apps with access to your

account” page Once a month (

Q

2

22

) and to reapprove apps

Once a year (Q

2

23).

to third-party apps. For example, P210 stated:

I would want to know exactly what those apps have ac-

cess to. Actually wish there was more information there.

Seems like it is a little generic.

New Features and Design Changes.

In an open-ended re-

sponse question, we asked what new features participants

would like to add to the “Apps with access to your account”

page (

Q

2

21

). Many participants (

n = 61

) wanted the page to

display more detailed information and for the account access

to be more transparent, e.g, “An option to have even more

detail of what was exactly being accessed” (P68). A common

(

n = 19

) request was an app usage or data access log, like

when P17 replied:

I think it would be useful for them to show when I last

used an app and when the app last used my data, to see if

the app is using my data even when I have not used the

app in a while.

Another request (

n = 12

) was detailed permission explana-

tions, for instance when P174 demanded,

DETAILED information about what is available to third

party apps. Not just “access to your personal informa-

tion,” but “access to: your full name, age, date of birth,

street address.”

Permissions level control is also desired, e.g., “The ability

to remove certain accesses that I don’t think the app needs”

(P143), and some requested access timeouts, e.g., “Auto re-

moval of apps after 3 months of no use” (P156).

We asked participants how often they would like to be

reminded if Google were to provide an email reminder to

review their “Apps with access to your account” page (

Q

2

22

).

Most participants (

n = 117

;

55 %

) responded Once a month,

another 37 % (n = 79) want a reminder Once a year.

10 48 42 79 34

6 17 93 96

I would want to designate specific data as private and

inaccessible to third−party apps.

I would want third−party apps to seek my approval each time

they access my Google account.

0% 25% 50% 75% 100%

Strongly disagree Disagree Neither agree n...

Agree Strongly agree

Figure 12: Over half of participants Strongly Agree or Agree

they want third-party apps to seek approval each time they ac-

cess their Google account (

Q

2

25

), and roughly

90 %

of partic-

ipants Strongly Agree or Agree they want to designate specific

data as private and inaccessible to third-party apps (

Q

2

26

).

One participant managed to submit a non-response, and is

excluded from this data.

Reapproving Apps.

Additionally, we asked participants if

Google required them to reapprove the third-party apps with

access to their account, how often would they want to provide

reapproval (

Q

2

22

). A majority of participants (

n = 127

;

59 %

)

want to reapprove apps Once a year, while

29 %

(

n = 63

) want

a reminder Once a month. Please see Figure 11 for the full

results of these questions.

When we asked participants if they would want third-party

apps to seek approval each time they access their Google

account (

Q

2

25

) over half (

n = 113

;

53 %

) agreed they want

third-party apps to seek approval each time they access their

Google account, while

27 %

(

n = 58

) disagreed. We also

asked participants if they want to designate specific data (e.g.

certain emails, individual contacts, particular calendar events)

as private and inaccessible to third-party apps (

Q

2

26

), and

most participants (

n = 189

;

89 %

) agreed, few (

n = 3

;

1 %

)

disagreed. Please refer to Figure 12 for the full results.

5 Discussion and Conclusion

In this section we offer conclusions and recommendations

for managing third-party apps and SSOs that access users’

Google accounts. We first discuss issues with handling dis-

used third-party access and the potential to have cascading

removal. Next, we focus on issues with transference of trust

from Google to third-party apps, and finally, we offer some

design improvement for “Apps with access to your account”

based on our observations and qualitative feedback.

Handling Stale Account Access.

This research identifies

the need for limiting account access for unused, forgotten, or

3408 31st USENIX Security Symposium USENIX Association

removed third-party apps. Participants either had not recently

used or were unsure when they had last used one in five third-

party apps in our study. Additionally, most participants ( 80%)

rarely or never reviewed the third-party account access. At

the same time, nearly half of participants wanted to modify

access after the study and over 70% wanted to do so within

six-months. Most participants indicated they would remove

unused apps or apps they no longer recall authorizing, but

the current interface for reviewing third-party apps does not

provide a record of last use.

Participants also expressed strong support (95%) for email

reminders to review their third-party apps at least once a year.

Moreover, participants highly favored (91%) a requirement to

reapprove account access at least once a year. Google could

send email reminders to all users to review “Apps with access

to your account” with additional details provided regarding

unused third-party apps. Review request could also be more

directed, perhaps asking users to review a single app at a time

so as not to overburden. Another possibility is to auto-expire

apps that have not been recently used or did not recently make

an API call. Facebook implemented a similar policy following

the Cambridge Analytica scandal [

23

], to expire app access

periodically and then require users to reauthorize.

Cascading Removal.

Participants were surprised to find

apps in their “Apps with access to your account” page that

they believed were removed in other places. For example,

many smartphone applications leverage a Google Account

for functionality and authentication, and in these case, partici-

pants who removed that smartphone app believed they also

remove the third-party app access.

While expiring third-party apps, see above, would help

address this issue, cascading removal could provide addi-

tional support for users who attempt to manage access to their

Google account. A third-party app, or the user’s account, can

send a notification when a secondary application that lever-

ages the third-party app is removed from a user device, which

in turn allows the user to deactivate the third-party app access.

All Or Nothing Permissions.

Users must approve all per-

mission requests for third-party apps or none, and many of

permission requests may not be fully understandable, contex-

tualized, or presented at the time of the access request. After

granting access, the “Apps with access to your account” offers

no permission-level control to limit account access; the only

option is to completely remove access.

Even without fine-grain controls, most participants in our

study find most permissions to be necessary for the functional-

ity of their apps; however, they consider some permissions un-

necessary and concerning, especially those that allow access

to view personal information that may include data beyond

just name and email address. Our qualitative data shows that

this practice is forcing users to consider a tradeoff between

their personal privacy and the benefits of third-party apps or

the convenience of SSOs.

Furthermore, when prompted to describe new features, par-

ticipants stated a desire for permission level controls, and

we recognize such a feature could have negative impacts on

the functionality of third-party apps. However, we recom-

mend that Google provide permissions level control for users’

personal data, for instance: “See your gender,” “See your

age group,” “View your street addresses,” “See and download