The Efficiency-Equity Tradeoff of the Corporate Income Tax:

Evidence from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

Patrick J. Kennedy

Berkeley and JCT

(Job Market Paper)

Christine Dobridge

FRB

Paul Landefeld

JCT

Jacob Mortenson

JCT

(Click for latest version)

October 31, 2022

Abstract

This paper studies the effects of an historically large federal corporate income tax cut on U.S.

firms and workers, leveraging quasi-experimental policy variation from the 2017 law known as

the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. To identify causal effects, we use employer-employee matched

federal tax records and an event study design comparing similarly-sized firms in the same

industry that faced divergent tax changes due to their pre-existing legal status. Reductions

in marginal income tax rates cause increases in sales, profits, investment, and employment,

with responses driven by firms in capital-intensive industries. Workers’ earnings gains are

concentrated in executive pay and in the top 10% of the within-firm income distribution, while

workers in the bottom 90% of the distribution see no change in earnings. Interpreted through

the lens of a stylized model, our estimates imply that a $1 marginal reduction in corporate tax

revenue generates an additional $0.10 in output, with 78% of gains flowing to the top 10% of

the income distribution. Overall, the results imply that corporate tax cuts improve aggregate

efficiency but exacerbate inequality.

Eric Heiser provided outstanding research assistance. We thank Alan Auerbach, Nano Barahona, Tom Barthold,

David Card, Benjamin Faber, Pablo Fajgelbaum, Penelopi Goldberg, Amit Khandelwal, Patrick Kline, Michael Love,

Emi Nakamura, Cristóbal Otero, Andrés Rodríguez-Clare, Jesse Rothstein, Nina Roussille, Emmanuel Saez, Benjamin

Schoefer, David Sraer, Jón Steinnson, Damián Vergara, Danny Yagan, Gabriel Zucman, and seminar participants at

Berkeley and the 2022 NBER Conference on Business Taxation at Stanford for constructive comments and suggestions.

Kennedy acknowledges financial support from the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship

Program. This research embodies work undertaken for the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation, but as members of

both parties and both houses of Congress comprise the Joint Committee on Taxation, this work should not be construed

to represent the position of any member of the Committee. The views and opinions expressed here are the authors

own. They are not necessarily those of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, its members, or its staff.

1 Introduction

We study the effects of corporate income tax cuts on firms and workers in the United States,

where in 2017 Congress enacted the most sweeping and significant legislation on American federal

business taxation in a generation. Commonly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the

legislation introduced reforms to corporate marginal income tax rates, investment incentives,

and taxation of foreign income, among several other provisions of the tax code. Collectively,

the breadth of these provisions and the magnitude of the tax rate changes constitute the largest

overhaul of American business taxation since the Tax Reform Act of 1986, providing a rare and

sharp natural experiment to shed light on contemporary research and policy debates.

Even as governments around the globe have dramatically reduced corporate income tax rates

over the past half-century — from an unweighted average country worldwide statutory tax rate of

40% in 1980 to just 23% in 2021 (Tax Foundation 2021) — policymakers and researchers today

fiercely debate the costs and benefits of declining corporate tax burdens. Advocates for tax

cuts argue that lower rates increase investment, growth, and workers’ living standards, while

opponents argue they do little to boost growth and primarily benefit the wealthy.

In this paper we bring new evidence to these debates. Our empirical analysis specifically

studies the core provisions of TCJA affecting firms’ statutory marginal income tax rates, using

a rich employer-employee matched panel dataset constructed from large random samples of

firm- and worker-level federal tax records. The data allow us to observe a holistic set of firm

outcomes — such as sales, profits, shareholder payouts, and investment — and to merge them

with worker-level data on employment and annual labor earnings.

Our main empirical strategy leverages an event study design to compare the outcomes of

similarly-sized firms in the same industry that faced divergent changes in their tax treatment.

In particular, TCJA cut the top marginal tax rate for a legal entity type of firms known as

C-corporations from 35% to 21% (a 40% reduction). At the same time, TCJA cut the implied top

marginal tax rate for a separate legal entity type of firms known as S-corporations from 39.6%

to 37% (a 6% reduction), and also introduced a new tax deduction that, for many of these firms,

further reduced the top marginal rate to 29.6% (for a cumulative 25% reduction).

1

C-corporations

and S-corporations operate in the same industries, overlap in their firm size distributions, and

faced broadly similar tax burdens prior to TCJA, inviting a natural comparison.

We exploit the fact that the average C-corp received a significantly larger tax cut than the

average S-corp to provide the first exhaustive evidence of these corporate tax changes on firms’

sales, profits, shareholder payouts, investment, and employment, as well as on workers’ annual

1

The top marginal tax rate for S-Corporations is implied because, unlike for C-Corporations, it must be computed as

a weighted average of the marginal tax rates faced by each firms’ individual owners and cannot be directly inferred from

firms’ tax records. The newly introduced tax deduction for S-corporations is known as the Qualified Business Income

(QBI) deduction. We discuss both points in greater detail in Sections 2 and 3. As we will describe, the main differences

between the firm types are that C-corporations may have unlimited shareholders and pay taxes directly to the federal

government, whereas S-corporations face greater shareholder restrictions and pay taxes indirectly to the government

via the individual tax filings of their shareholders.

1

earnings. As in Yagan (2015), the identifying assumption of our research design is not random

assignment of C or S status; rather, it is that outcomes for C- and S-corps would have trended

similarly in the absence of the tax cuts. Event studies indicate that outcomes of comparable C-

and S-corps were on similar trends prior to TCJA, and we further implement a series of robustness

checks to validate that our causal estimates are driven by changes in top marginal tax rates rather

than other features of the law, superficial tax shifting behaviors, or unrelated economic forces

differentially affecting C- and S-corps at the same time as TCJA.

Our benchmark regression specifications, which compare trends in outcomes of C- versus

S-corps controlling for firm and industry-size-year fixed effects, indicate that corporate income

tax cuts cause economically and statistically significant increases in firms’ sales, profits, payouts

to shareholders, employment, and real investment in capital goods. Responses are concentrated

in capital intensive industries, and are not larger for smaller or cash-constrained firms, suggesting

that effects are driven by a reduction in the cost of capital rather than by liquidity effects.

Our benchmark estimate of the federal corporate elasticity of taxable income, a key parameter

for measuring the magnitude of tax distortions, is 0.38 (s.e.=0.13). This elasticity is smaller than

most comparable estimates generated from variation in state and local corporate taxes, but larger

than most estimates on personal income taxes. Since businesses are less mobile at the federal level

than at the state or local level, and since a large literature documents that personal labor supply

elasticities are small, we interpret this evidence as consistent with the common economic intuition

that tax distortions vary proportionally with factor mobility.

Moving to the worker-level evidence, quantile regressions show that annual earnings do not

change for workers in the bottom 90% of the within-firm distribution, but do increase for workers

in the top 10%, and increase particularly sharply for firm managers and executives. Unlike other

outcomes such as employment and investment, we find that executive earnings increase in both

capital and non-capital intensive industries. Moreover, executive pay increases are only weakly

correlated with changes in firm sales, profits, or sales growth relative to other firms in the same

industry. Synthesizing this evidence, we estimate that approximately 10% of the executive pay

bump is driven by improved firm performance, while the remaining 90% is plausibly attributable

to rent-sharing or executive capture.

Descriptively, relative to the population of workers in our sample, the executives and workers

in the top 10% who benefit from higher earnings are typically older, have longer employment

tenures at the firm, and are more likely to be men. However, we find little evidence that earnings

effects vary heterogeneously by gender, age, or tenure after controlling for workers’ place in the

within-firm earnings distribution.

To evaluate the effects of corporate tax cuts on tax revenue and output, we combine the

reduced-form elasticities from the empirical analysis with a stylized model of firm owners and

workers. Using the model, we estimate that a $1 marginal reduction in the tax rate generates

an additional $0.10 increase in output. Corporate tax revenues decline by $0.87, with behavioral

responses of firms and workers modestly blunting mechanical revenue losses, and consistent with

2

the notion that contemporary top corporate marginal income tax rates in the US are below the

revenue-maximizing rate.

To evaluate distributional impacts, we estimate the short-run incidence of corporate tax cuts

on several factor groups — firm owners, executives, and high- and low-paid workers — as the

share of total output gains accruing to each factor. Combining our reduced form elasticities

with moments from the tax data, we find that approximately 56% of gains flow to firm owners,

12% flow to executives, 32% flow to high-paid workers, and 0% flow to low-paid workers. We

then go beyond factor incidence to estimate effects across the income distribution, accounting for

the empirical fact that many workers are also firm owners (that is, they hold equity portfolios)

and many firm owners also work. Using data on the distribution of capital ownership, we find

that approximately 78% of the gains from tax cuts accrue to the top 10% of earners, and 22% of

gains flow to the bottom 90%. Leveraging the empirically observable geographic distribution of

workers and income, we further find that these benefits are disproportionately concentrated in the

Northeastern and Western regions of the United States, and particularly among workers in large

and high-income cities.

This paper builds on a large body of research that studies the effects of corporate taxes on

profits, investment, shareholder payouts, employment, wages, and executive compensation.

2

Early seminal studies use aggregate or firm-level panel data and estimate two-way fixed effect

models to study policy variation across countries or industries (Hall and Jorgenson 1967;

Cummins, Hassett, and Hubbard 1994; Cummins, Hassett, and Hubbard 1996; Goolsbee 1998;

Hassett and Hubbard 2002). More recent contributions use detailed administrative microdata and

modern econometric methods to exploit geographic policy variation (Link, Menkhoff, Peichl, and

Schüle 2022; Duan and Moon 2022; Garrett, Ohrn, and Suárez Serrato 2020; Giroud and Rauh

2019; Fuest, Peichl, and Siegloch 2018; Suárez Serrato and Zidar 2016; Becker, Jacob, and Jacob

2013), industry-level variation in exposure to tax deductions or credits (Curtis, Garrett, Ohrn,

Roberts, and Serrato 2021; Ohrn 2022; Dobridge, Landefeld, and Mortenson 2021; Ohrn 2018;

Zwick and Mahon 2017; House and Shapiro 2008), and firm-level policy variation induced by

plausibly arbitrary legal or circumstancial distinctions (e.g., Boissel and Matray 2022; Moon 2022;

Carbonnier, Malgouyres, Py, and Urvoy 2022; Bachas and Soto 2021; Risch 2021; Alstadsæter,

Jacob, and Michaely 2017; Patel, Seegert, and Smith 2017; Yagan 2015; Devereux, Liu, and Loretz

2014).

Despite major advances in recent research, there are natural reasons to question whether

existing evidence is generalizable to understanding the effects of corporate tax cuts in the context

of TCJA. Evidence from subnational governments, small developing countries, or small firms may

2

Other outcomes studied in the literature include: establishment counts (e.g., Suárez Serrato and Zidar 2016; Giroud

and Rauh 2019); consumer prices (Baker, Sun, and Yannelis 2020); innovation and the mobility of inventors (Akcigit,

Grigsby, Nicholas, and Stantcheva 2021); international tax competition (Devereux, Lockwood, and Redoano 2008); the

location and investment decisions of multinational firms (Becker, Fuest, and Riedel 2012; Devereux and Griffith 2003);

tax avoidance and profit shifting (Garcia-Bernardo, Jansk

`

y, and Zucman 2022; Desai and Dharmapala 2009; Auerbach

and Slemrod 1997; Slemrod 1995; Hines and Rice 1994); and macroeconomic performance (Cloyne, Martinez, Mumtaz,

and Surico 2022; Zidar 2019; Romer and Romer 2010, Lee and Gordon 2005). These outcomes are beyond the scope of

this paper.

3

have limited applicability to major reforms in a large advanced economy such as the United States

(Auerbach 2018). This concern is especially salient with respect to the U.S. federal corporate

income tax, where the tax base is broader, top tax rates are higher, revenues are orders of

magnitude larger, and factors of production are considerably less mobile. Moreover, economic

theory predicts that alternate tax instruments — such as dividend taxes, capital gains taxes, or

narrowly targeted corporate tax deductions and credits — have very different effects than the

corporate income tax (Auerbach 2002; Hassett and Hubbard 2002). In this light, it is not surprising

that, due to differences in both normative and empirical worldviews, debates over the effects of

TCJA remain hotly contested by researchers and policymakers (Barro and Furman 2018).

Well-identified evidence on the federal corporate income tax has remained scarce for three

reasons. First, federal tax reforms are rare historical events, leaving limited policy variation for

researchers to study. Second, digitized administrative microdata was previously unavailable

to researchers, constraining the scope and precision of empirical analyses. Third, even when

countries do change their tax rates, it is difficult for researchers to identify credible counterfactuals

for causal inference, particularly as the parallel trends assumption underlying cross-country

difference-in-difference analyses are challenging to defend in disparate socioeconomic and

institutional settings.

This paper overcomes these limitations to provide clear and transparent evidence on the effects

of corporate tax cuts on firms and workers. In doing so, we make four main contributions to the

literature.

First, we study a rare policy change that generated historically large within-country variation in

federal corporate income tax rates, and moreover generated variation even across similarly sized

firms in the same industry. As a share of GDP, the TCJA tax cut is orders of magnitude larger

than previous studies that focus, for example, on changes in state or local corporate taxes, which

tend to have lower rates and a smaller tax base (e.g., Giroud and Rauh 2019; Fuest, Peichl, and

Siegloch 2018; Suárez Serrato and Zidar 2016). The large magnitude of the tax cut is relevant on

both theoretical grounds (according to the conventional view that tax distortions are proportional

to the square of the tax rate, as in Harberger 1964) and on purely empirical grounds (since ex-ante

it is unclear whether existing evidence can be extrapolated to the case of an outlier).

Second, we complement the large shock with detailed employer-employee matched tax records

that allow us to observe an unusually holistic set of firm- and worker-level outcomes. We build

on frontier research that uses employee-level data to provide a nuanced account of corporate tax

incidence on different types of workers (Carbonnier, Malgouyres, Py, and Urvoy 2022; Risch 2021;

Dobridge, Landefeld, and Mortenson 2021; Fuest, Peichl, and Siegloch 2018), and extend existing

work by empirically estimating geospatial incidence and incidence on firm owners. In contrast

to studies that do not directly observe profits (e.g., Suárez Serrato and Zidar 2016), the richness

of our data allows us to estimate incidence using fewer assumptions than are typically required

when data availability are more limited.

Third, we contribute to a growing literature that seeks to understand the effects of TCJA on

4

the U.S. economy. Researchers have studied impacts on macroeconomic performance (Gale and

Haldeman 2021; Gale, Gelfond, Krupkin, Mazur, and Toder 2019; Kumar 2019; Barro and Furman

2018; Mertens 2018), international and intertemporal profit shifting (Garcia-Bernardo, Jansk

`

y,

and Zucman 2022; Dowd, Giosa, and Willingham 2020; Clausing 2020), pass-through businesses

(Goodman, Lim, Sacerdote, and Whitten 2021), executive compensation (De Simone, McClure,

and Stomberg 2022), capital structures (Carrizosa, Gaertner, and Lynch 2020), and regional or local

economic outcomes (Kennedy and Wheeler 2022; Altig, Auerbach, Higgins, Koehler, Kotlikoff,

Terry, and Ye 2020). Our study differs from existing research in that we specifically study the

effects of TCJA’s marginal corporate income tax cuts on firm- and worker-level outcomes using

rich admistrative microdata and a quasi-experimental research design leveraging cross-firm policy

variation.

Finally, we contextualize our findings from this historical episode in broader debates about

efficiency and equity in national tax and transfer systems (Carbonnier, Malgouyres, Py, and

Urvoy 2022; Bachas and Soto 2021; Risch 2021; Hendren and Sprung-Keyser 2020; Fuest,

Peichl, and Siegloch 2018; Suárez Serrato and Zidar 2016; Devereux, Liu, and Loretz 2014;

Arulampalam, Devereux, and Maffini 2012; Gruber and Rauh 2007). With respect to efficiency,

our model-based estimates of the marginal output gains from cutting the federal corporate income

tax are approximately 1.5 to 2 times as large as the literature-implied marginal gains from cutting

personal income or payroll taxes. With respect to equity, our results contrast with much existing

research in that we find the incidence of the corporate falls heavily on capital and highly-paid

workers. Assessing incidence across the income distribution, we estimate that corporate income

tax cuts are similarly regressive relative to personal income tax cuts, but markedly less progressive

than payroll tax cuts. We note that our results capture short-run responses and do not account

for potential changes in government spending or after-tax redistribution, which are important

considerations for policymakers but beyond the scope of this research.

The rest of the paper proceeds as follows. Section 2 summarizes key features of the Tax Cuts

and Jobs Act, including its legislative history, institutional context, and major policy changes.

Section 3 describes data sources and variable definitions. Section 4 details our empirical strategy

and presents results. Section 5 presents a stylized model that we use to estimate the revenue

impacts, excess burden, and incidence of TCJA’s corporate tax cuts. Section 6 concludes with a

discussion of the results.

2 Institutional Setting: The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act

2.1 Legislative History

In 2017 Congress took on the task of reforming federal business tax policy, with the stated aims

of increasing capital investment, economic growth, and international competitiveness.

3

Following

3

The policy reforms were first proposed in a blueprint document released by Republicans in the House of

Representatives in June 2016, available here.

5

several months of political negotiations and policy proposals, in December 2017 Congress and

the President enacted Public Law 115-97, more commonly known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act,

or TCJA. The law included provisions affecting many aspects of the federal business tax code,

including corporate income tax rates, investment incentives, and taxation of foreign income. Most

policy changes were implemented beginning in tax year 2018, although some provisions, such as

the investment incentives that we will later discuss, were applied to tax year 2017. Our aim below

is not to exhaustively detail TCJA’s numerous reforms — for reviews of significant provisions

see Auerbach (2018) and Joint Committee on Taxation (2018) — but rather to illuminate the key

institutional details and policy variation that we leverage in our empirical analysis.

2.2 C-Corporations vs. S-Corporations

At the heart of TCJA was an overhaul of the income tax schedules facing two legally distinctive

types of businesses, known as C-Corporations and S-Corporations. Combined, C- and S-corps

account for approximately 70% of total U.S. employment and 74% of total payrolls, with

government, non-profits, and non-corporate private businesses comprising the remainder (Census

Bureau 2019). Our analysis focuses exclusively on the corporate sector, as other entity types face

different tax and regulatory regimes, and are beyond the scope of this paper. Below we describe

salient legal differences between C- and S-corps.

C-Corporations

C-corps are required to pay income taxes directly to the federal government, may be private or

public, and are subject to both corporate income taxes (paid on corporate profits) and dividend

taxes (paid by shareholders on profits distributed as dividends). Prior to TCJA, C-corps faced a

progressive tax schedule with eight income brackets and a top marginal rate of 35%. After TCJA,

these brackets collapsed to a single uniform 21% tax rate. Appendix A.1 documents the evolution

of top marginal income tax rates for C-corps in the United States since 1909, illustrating the historic

nature of this large and rare tax cut, and Appendix A.2 details the collapse of the progressive

corporate income brackets following TCJA. Appendix A.3 puts the U.S. corporate tax in a global

perspective, and Appendix A.4 benchmarks the magnitude of the TCJA corporate tax cut against

other recent studies in the literature.

S-Corporations

S-corps do not pay taxes directly to the federal government. Rather, the firms’ profits are

distributed to the individual owners of the firm, who pay taxes on profits as ordinary income and

can deduct any losses. S-corps may have up to 100 shareholders, all of whom must be U.S. citizens

and not businesses or institutional investors, and are not permitted to sell shares on publicly

traded stock exchanges. Unlike C-corps, S-corps do not face corporate income taxes, nor are their

distributed profits subject to the dividend tax.

6

Prior to 2018, owners of S-corps faced a top marginal income tax rate of 39.6%. TJCA then

provided two distinct types of tax relief to owners of S-corps. First, it reduced the top personal

income tax rate from 39.6% to 37%. Second, it introduced a 20% tax deduction on qualified business

income that further reduced the effective marginal tax rate on S-Corp income for most high-income

tax-payers from 37% to 29.6%. This tax deduction — known as the Qualified Business Income

(“QBI”) deduction, or as “Section 199A” after the applicable section of the internval revenue code

— is claimable by most but not all owners of S-corps. Since the QBI limitations are complex and

not crucial for our empirical analysis, we abstract from details here and provide more details in

Appendix A.5.

Entity Type Choice and Switching

Firms must elect either C or S status upon incorporating. The decision to choose one corporate

form over the other may reflect a variety of considerations, including access to capital (recall that

S-corps may not be publicly traded) and tax planning (recall that C-corps must pay entity-level

taxes and are subject to dividend taxes on distributed profits). After electing C or S status,

switching entity types is costly, rare, and subject to regulatory restrictions. Thus, a firm’s entity

type prior to TCJA is strongly related to the tax rate change it faced after TCJA, and endogenous

switching is not a concern for our analysis.

2.3 Policy Variation in Marginal Income Tax Rates

Figure 1 shows the evolution of marginal income tax rates and tax burdens for C- and S-corps

in the years before and after TCJA. Panel A shows the sharp reduction in top statutory marginal

income tax rates for C-corps, as well as the change in implied top statutory marginal income tax

rates for S-corps depending on whether or not they are eligble for the QBI deduction.

Panel B shows the change in observed marginal tax rates from our analysis sample of large

firms with at least 100 employees. Entity-level tax rates and taxes paid are imputed for S-corps by

linking to returns of S-corp owners, as we will describe in detail in the following section. Observed

average marginal tax rates are lower than top statutory rates for several reasons. First, in any

given year some firms will have non-positive taxable income (for example, if they earn zero or

negative profits) and thus face a marginal tax rate of zero. Second, C-corps prior to TCJA faced a

graduated tax rate schedule. Third, our measure of the marginal tax rate for S-corps is computed

as a weighted-average of the tax rates faced by their owners, some of whom may not be in the top

tax bracket.

Panel C underscores the economic significance of the tax cuts in dollar terms, documenting the

observed average change in corporate taxes per worker for C- and S-corps. The panel shows that

average taxes per worker declined from 2016 to 2019 by approximately $1,600 per worker (≈28%)

for C-corps, and by approximately $800 per worker (≈13%) for S-corps.

Most importantly, all three panels show that, on average, C-corps received a significantly larger

tax cut than S-corps due to TCJA, illustrating the key policy variation that we use in our empirical

analysis to identify causal effects.

7

FIGURE 1: MARGINAL INCOME TAX RATES AND TAXES PER WORKER

Panel A: Top MTR (Statutory) Panel B: Average MTR (Observed)

S Corps

C Corps

W/out QBI

W/ QBI

(%)

10

20

30

40

50

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Top Marginal Income Tax Rates

.1

.15

.2

.25

.3

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

S Corps C Corps

Marginal Tax Rate

Panel C: Taxes Per Worker (Observed)

S Corps

C Corps

Taxes/Worker ($)

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Notes: Panel A shows top statutory marginal income tax rates for C and S Corporations before and after enactment of

TCJA. Panel B shows the average MTRs observed in our data analysis sample of large firms with at least 100

employees; we discuss the data construction and variable definitions in Section 3. Panel C shows the change in taxes

per worker paid by C- and S- corps observed in the data over the sample period.

8

3 Data

We use a panel of employer-employee matched annual federal tax records from tax years 2013

to 2019. We begin the sample period in 2013, allowing us to compare trends in the outcomes

of C- and S-corps several years before TCJA, and end the sample in 2019, prior to the onset of

the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Below we describe the data sources and sample construction,

provide variable definitions, and present descriptive statistics. We provide additional details about

the data cleaning procedures in Appendix B.

3.1 Corporate Tax Returns

We study firms in the corporate Statistics of Income (SOI) files produced by the U.S. Internal

Revenue Service (IRS). The corporate SOI files include stratified random samples of corporate tax

returns from both C-corps (from IRS Form 1120) and S -corps (from IRS Form 1120S). IRS produces

and cleans these random samples to estimate aggregate statistics and to provide government

agencies with essential data for development of legislation and policy analysis. The corporate

tax returns allow us to observe firms’ domestic sales, costs, profits, investment, and taxes paid, as

well as their year of incorporation and industry. The IRS over-samples large firms with known

probability weights, and the samples are designed as rolling panels so as to allow for longitudinal

analyses.

4

We impose the following two sample restrictions on the SOI panel, yielding an analysis sample

of approximately 11,600 unique firms and 81,000 distinct firm-year observations.

First, we restrict the sample to large firms, defined as those with at least 100 employees and $1

million in sales in every year of our pre-treatment period from 2013 to 2016. There are two reasons

for restricting the sample to large firms. Large firms account for the lion’s share of corporate

economic activity, comprising approximately 90% of corporate sales, 70% of corporate taxes, and

67% of corporate employment.

5

Moreover, many small C-corps faced tax increases (rather than

tax cuts) after TCJA due to the flattening of corporate income tax brackets to a uniform 21% rate.

Including smaller firms would thus require significantly complicating our empirical design, which

simply compares outcomes of similar C- and S-corps over time. The large firm restriction both

allows us to study the most economically significant firms and to employ a more transparent and

credible research design.

Second, we balance the panel and drop firms that ever switch entity types from C to S or from

S to C over the course of our sample period. Balancing the panel ensures that our results are

not driven by the changing composition of firms in the SOI samples. Because entity-switching is

rare, dropping switchers from our sample excludes only approximately 4% of firms, collectively

comprising less than 0.5% of corporate sales or profits.

4

For additional details on construction of the SOI samples, see documentation provided by the IRS here.

5

Authors’ calculations using IRS SOI data.

9

3.2 Individual Tax Returns

We complement the sample of corporate tax records with several sources of individual-level

administrative records.

First, we merge the sample of corporate tax returns with the universe of worker-level filings of

IRS Form W-2, which provides information on workers’ annual wage earnings from each of their

employers. Employers are required each year to share copies of form W-2 both with their workers

and with the IRS, allowing us to observe the earnings of all workers even if they had no federal tax

liability or did not file a personal income tax return.

Second, we collect information about the owners of S-corps in our sample from the universe

of filings of IRS Form 1099-K1, which provides data on the income received by owners of

S-corps from each of their pass-through businesses each year, including pass-through income from

non-corporate partnerships. As we will describe below, we complement this information with data

from IRS Forms 1040 to compute implied marginal income tax rates and federal taxes paid for S

corporations.

Finally, we observe individuals’ age and gender from the Master Database maintained by the

Social Security Administration (SSA). We also observe their residential location using data from

Kennedy and Wheeler (2022).

3.3 Variable Definitions and Measurement

Our empirical analysis uses information on firm-level tax rates, taxes paid, sales, profits,

investment, employment, and shareholder payouts. We also use data on workers’ employment

and annual wage and salary earnings. We take care to measure these variables consistently

over time, such that our outcomes are not affected, for example, by changes in the tax base or

in reporting requirements on tax forms. We provide additional details on variable definitions,

including specific forms and line item numbers, in Appendix B.

Marginal Tax Rates

Our primary explanatory variable of interest is the marginal income tax rate paid by firms. For

C-corps, we observe taxable income and directly infer each firm’s marginal income tax rate using

the federal corporate income tax schedules reproduced in Appendix Table A.1. For S-corps, we

observe each owner’s taxable income from their personal tax returns, and directly infer their

personal marginal income tax rate using the federal personal income tax schedules as reproduced

in Appendix Table A.1. We then compute the implied corporate marginal tax rate for the firm as a

weighted average of the marginal personal income tax rates faced by the firms’ owners, where the

weights are given by the share of ordinary business income distributed to each owner from that

firm. For example, if an S-corp has two owners who receive an equal share of that firm’s business

income, facing marginal tax rates on their individual income of 25% and 35%, respectively, then

we compute the implied corporate marginal tax rate as (.5 ∗ .25) + (.5 ∗ .35) = 30%. Appendix

10

Figure B.1 shows the sample distribution of corporate MTRs for both S- and C-corps before and

after TCJA.

Taxes Paid

For C-corps, we directly observe total tax payments to the federal government on Form 1120. For

S-corps, which do not pay entity-level taxes, we must estimate tax payments using information

from the individual-level tax records of the firms’ owners. To do so, we first compute each owner’s

average tax rate from Form 1040 as total federal tax divided by taxable income. We also record each

owner’s total net ordinary business income from Form 1040 Schedule E, and estimate total business

taxes paid on this income by multiplying it by the owner’s average tax rate. We bottom code

total business taxes at zero, ensuring in our calculations that owners do not pay tax on business

losses. For each owner, we allocate her total business tax payments to each firm that she owns

in proportion to the share of ordinary business income received from that business. Finally, we

sum up the total tax payments of each firm’s owners to record an estimate of total firm-level tax

payments. We provide additional details about these computations in Appendix B.

Sales, Costs, and Profits

We measure firm sales as gross receipts. Pre-tax profits are defined as sales minus cost of goods

sold, which includes both material and labor inputs. An advantage of this profit measure is that

it is simple, transparent, consistent over time, and invariant to tax law and corporate form. As

a robustness check, we also construct a harmonized measure of earnings before interest, taxes,

depreciation, and amoritization (EBITDA), described in B. After-tax profits are equal to pre-tax

profits minus taxes paid.

Dividends, Share Buybacks, and Total Payouts

Dividends are defined as total cash and property payments to shareholders. Share buybacks are

defined as non-negative changes in treasury stock, and total payouts are measured as the sum of

dividends and share buybacks.

Investment

Net investment is defined as the change in the dollar value of capital assets, where capital assets are

equal to the book value of tangible investment minus capital asset retirements and accumulated

book depreciation. We also report results on new investment, defined as the sum of capital

expenditures reported on IRS Form 4562. These tax forms include information on firms’ purchases

of new capital assets such as machinery, computers, vehicles, office furniture, and structures. Firms

report these investments according to the lifespan of the investment, which affects the horizon

of capital tax deductions available to the firm. We decompose new investment into “short-life”

equipment with depreciation schedules of less than or equal to 10 years (such as light machinery,

11

computers, and vehicles), “long-life” equipment with longer depreciation schedules (such as

heavy machinery), and structures (such as new factories or office buildings).

Employment, Earnings, and Executive Compensation

We measure firm employment as the total number of unique individuals with a W-2 issued by

the firm. Firms with complex ownership structures often use multiple employer identification

numbers, and we use crosswalks to improve the linkage between W-2s and their ultimate parent

companies (see Joint Committee on Taxation 2022). Workers’ annual earnings are defined as

Medicare wages from the W-2, which capture wage, tip, and salary income even if it is not taxable.

Total firm payrolls are the sum of workers’ annual earnings. Because employment, earnings, and

payrolls are always strictly positive in our sample, we take logs of these outcomes in the empirical

analyses.

Firms report compensation of officers on Forms 1120 and 1120s, which we use to measure

executive pay. Officer designations are determined by state tax law, and reported compensation

captures several but not all components of executive pay, including: wage, salary, and bonus

income; stock options and grants, when exercised; and non-qualified deferred compensation.

However, this measure does not capture stock options or grants before they are exercised, and

does not include qualified incentive-based compenstion plans.

6

The measure thus represents a

lower bound on executive compensation.

We also construct an alternate proxy measure of executive compensation as the combined

annual W-2 earnings of the top five highest paid workers at the firm. This measure captures

compensation of high-ranking employees who may not qualify as officers for tax purposes.

Additional Firm Characteristics

We group firms into four time-invariant size bins with approximately comparable numbers of

observations based on their average employment in the pre-period years prior to 2017, where the

bins are: 100-199 employees; 200-499 employees; 500-999 employees; and 1000+ employees. We

also classify firms into time-variant industries using the NAICS-3 codes they report on Forms 1120

and 1120s. In the resulting data we observe 86 distinct industries and 280 distinct industry-size

bins.

Firm age is inferred from the firm’s year of incorporation, reported on the 1120. Firms are

classified as multinationals if their foreign sales share is greater than 1%, where foreign sales are

defined as the sum of gross receipts from all Controlled Foreign Corporations (that is, foreign

subsidiaries) reported on Form 5471. We measure capital intensivity at the industry level as capital

6

Designation of officers is detemined by the laws of the state or country where the firm is incorporated. Qualifed

deferred compensation plans include 401(k) and similar investment vehicles; these plans are subject to contribution

limits and regulatory restrictions, and investments are generally risk-free to workers. Non-qualified deferred

compensation plans are not subject to contribution limits and in principle are at risk if the firm declares bankruptcy,

although such losses are empirically rare. Qualified incentive-based compensation plans have a maximum deferral of

$100,000 per year and are taxed as long-term capital gains, and thus are not reported on the W-2.

12

assets divided by sales. Firms are classified as capital intensive if the mean of this ratio in the

pre-period is greater than the sample median, and others are classified as non-capital intensive.

Appendix B.3 shows that capital intensive firms are approximately equally distributed across the

firm size bins, and are not exclusively manufacturing firms.

Data Processing

We scale several outcomes — taxes, sales, costs, and profits — by firm sales in 2016, our baseline

year prior to the passage of TCJA. While it is common in economic research to estimate elasticities

by transforming regression outcomes using natural logs, doing so in our case is problematic

because taxes and profits are often zero or negative in a given year. Scaling firm variables

by baseline sales permits a natural economic interpretation of the regression coefficients in our

empirical analyses, allows us to study a range of outcomes such that they can be consistently and

easily compared, and is standard in the literature. In accordance with economic theory and prior

research, investment results are scaled by lagged capital, although for consistency across results

we also report results scaled by baseline sales in the Appendix. We also follow the literature in

winsorizing the top and bottom 0.1% of the scaled outcomes separately for C- and S-corps in each

year. Winsorizing ensures that our results are not driven by outliers or by measurement error,

and improves statistical precision. We also show that the empirical results are robust to alternate

winsorizing thresholds.

3.4 Descriptive Statistics

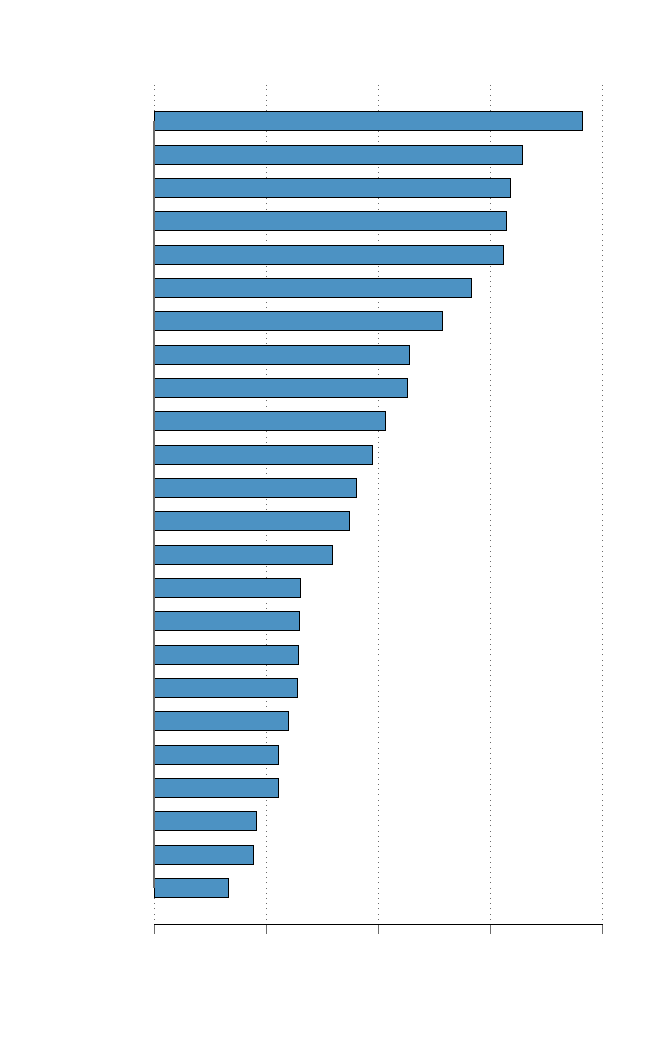

Panels A and B of Figure 2 show the distributions of log firm sales and log firm employment in our

sample, and illustrate broad overlap in the size distributions of C- and S-corps. The panels make

clear that the firm size distributions are strongly right-skewed, and that this skewness is more

pronounced for C-corps than S-corps. In robustness checks, we show that our empirical results are

insensitive to the inclusion or exclusion of very large C-corps; since they are qualitatively irrelevant

to the results, we include them in the main analysis sample.

Panel C of Figure 2 shows the NAICS-2 industry composition of the sample, and again reveals

broad overlap of C- and S-corps. Most industries have comparable shares of C- and S-corps. Some

sectors, such as management and professional services, have a relatively higher proportion of C-

than S-corps, while the reverse is true for others, such as construction and retail trade. Because

our event study analysis will use industry-size-year fixed effects to compare C- and S-corps in the

same industry and employment size bin, the observed sectoral overlap in the sample is more than

sufficient for our empirical design. In robustness checks, we show that results are insensitive to

the exclusion of industries in which the firm share of C-corps or S-corps exceeds 80%.

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics for our analysis sample from 2016. The mean firm in

the sample has annual sales of $1,046.9 million, earns pre-tax profits of $385.0 million, pays

$18.1 million in federal taxes, and makes real investments of $49.6 million per year. Mean firm

employment is 2,968 workers, and the average worker earns approximately $63,700 per year.

13

Consistent with Figure 2, columns 3-10 again underscore the right-skewness of firm size, especially

of C-corps, such that mean outcomes are significantly higher than medians and outcomes for

C-corps are higher and more variable than for S-corps.

7

FIGURE 2: FIRM SIZE DISTRIBUTIONS AND INDUSTRY COMPOSITION

Panel A: 2016 Sales Panel B: 2016 Employment

S-Corps

C-Corps

Density

0

.1

.2

.3

.4

$1mil $10mil $100mil $1bil $10bil $100bil

2016 Log Firm Sales

S-Corps

C-Corps

Density

0

.1

.2

.3

.4

.5

100 1K 10K 100K 1mil

2016 Log Firm Employment

Panel C: Industry Composition

Share of Firms

0

.05

.1

.15

.2

.25

.3

.35

Administration

Agriculture

Construction

Education

Entertainment

Finance

Food and Hotels

Health Care

Information

Management

Manufacturing

Mining

Other Services

Professional

Real Estate

Retail Trade

Transportation

Utilities

Wholesale Trade

C S

Notes: Panels A and B show the distribution of 2016 log firm sales and employment, respectively, for C- and S-corps in

the analysis sample. Panel C shows the NAICS-2 industry composition of firms in the sample.

7

All medians and other quantile statistics reported in this paper are fuzzed to protect taxpayer privacy; see

Appendix B for details.

14

TABLE 1: SUMMARY STATISTICS

All Firms C Corporations S Corporations

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5) (6) (7) (8) (9) (10)

Mean SD Mean SD p50 p90 Mean SD p50 p90

Taxes

Marginal Tax Rate 0.248 0.161 0.215 0.168 0.340 0.350 0.310 0.124 0.380 0.396

Federal Tax (mil) 18.1 164.7 26.1 202.7 0.6 24.7 2.9 13.1 0.6 6.8

Federal Tax Per Worker 6,050 11,503 6,382 12,480 1,229 17,567 5,415 9,326 1,669 15,187

Sales and Profits

Sales (mil) 1,046.9 5,976.2 1,467.0 7,327.1 152.7 2,276.4 244.4 636.3 117.6 463.5

Costs (mil) 654.5 4,667.9 905.8 5,733.4 69.5 1,130.1 174.5 521.9 72.5 345.3

Pre-Tax Profit (mil) 385.0 1,902.1 549.9 2,325.6 55.2 937.6 69.9 216.8 31.9 134.0

After-Tax Profit (mil) 366.9 1,799.7 523.8 2,199.9 52.2 906.3 67.0 211.7 30.2 127.1

EBITDA (mil) 155.9 1,240.2 227.0 1,525.2 11.6 273.0 20.1 64.4 8.1 38.6

Shareholder Payouts

Dividends (mil) 34.6 444.8 47.6 548.1 0.0 14.6 9.8 33.8 2.9 20.5

Share Buybacks (mil) 19.4 351.2 29.5 433.2 0.0 0.8 0.3 4.6 0.0 0.0

Total Payouts (mil) 56.5 708.4 80.8 873.0 0.0 24.9 10.1 34.1 3.0 20.9

Real Investment

Net Investment (mil) 17.9 404.4 26.6 498.8 0.0 23.3 1.3 15.0 0.0 5.3

Net Investment / Lagged Capital 0.16 1.36 0.15 1.26 0.01 0.39 0.18 1.53 0.01 0.42

New Investment (mil) 66.7 1,650.6 98.2 2,036.5 3.2 73.0 6.5 36.5 1.2 12.4

Employment and Earnings

Employment 2,968 21,533 4,041 26,241 510 5,986 918 5,262 340 1,454

Payroll (mil) 173 975 242 1,192 31 402 39 146 18 70

Mean Annual Earnings (thous) 63.7 59.2 68.2 62.8 56.5 111.3 55.1 50.3 49.0 80.9

Median Annual Earnings (thous) 46.2 25.4 49.6 28.0 42.9 84.8 39.7 17.7 37.6 60.2

Executive Pay

Executives’ Earnings (thous) 5,606 26,572 7,319 32,077 1,651 13,654 2,334 8,555 988 4,806

Mean Top 5 Earnings (thous) 1,187 3,329 1,496 3,950 458 3,203 596 1,388 341 1,059

Firm Characteristics

Firm Age 35 23 33 24 28 64 40 21 37 67

Multinational 0.24 0.32 0.10

Private 0.84 0.76 1.00

Capital Intensive 0.50 0.55 0.41

N Firms 11,647 7,645 4,002

Notes: Table shows summary statistics from 2016 for firms in the analysis sample. Medians and centile statistics are fuzzed to

protect taxpayer privacy. For data sources and variable definitions see Section 3.

15

4 Empirical Analysis

4.1 Empirical Strategy

We implement a transparent research design comparing trends in outcomes of C- and S-corps in

the same industry-size bin before and after TCJA. Our event study specification is given by:

y

ft

=

∑

t6=2016

β

t

C

f

∗ 1(year = t) + γ

f

+ α

is(f ),t

+

ft

(1)

where y

ft

is an outcome for firm f in year t; C

f

is a binary variable equal to 1 if firm f is a C-corp

or 0 if it is an S-corp; γ

f

is a firm fixed effect; and α

is(f ),t

is an industry-size-year fixed effect, where

the industry-size bins are constructed as described in Section 3.3. The coefficients of interest, β

t

,

capture the average differences in outcomes between C- and S-corps in the same industry-size

bin in year t. We use 2016 as the reference year, allowing us to compare C- and S-corp trends for

several years prior to TCJA and also to observe any potential anticipatory tax-shifting behaviors

beginning in 2017. Standard errors are clustered by firm.

The key identifying assumption permitting a causal interpretation of the β

t

coefficients is that

the outcomes of C- and S-corps would have trended similarly in the absence of TCJA’s changes to

firms’ marginal income tax rates. While this assumption is not directly empircally testable, there

are several reasons that parallel trends is likely to hold in our setting. First, Congressional passage

of TCJA was widely unexpected prior to the 2016 federal elections, and so firms had limited

scope to anticipate the reform and to adjust their behavior endogenously to the policy changes.

Second, our narrowly defined industry-size-year fixed effects imply that we make comparisons

among C- and S-corps that that compete in similar product markets and are subject to the same

industry-by-size specific supply and demand shocks. Third, Yagan (2015) finds that C- and S-corp

trends in real outcomes were statistically indistinguishable for all years in his sample period from

1996-2008, implying that C- and S-corps have historically responded similarly to macroeconomic

shocks and trends. Fourth, as we will show, our event studies show parallel trends in the outcomes

of C- and S-corps in the years directly prior to the policy reform. Lastly, in Section 4.8, we carefully

consider additional identification threats, and present a series of robustness checks to ensure that

our causal estimates are not driven by non-MTR features of the law, anticipation effects, superficial

tax-shifting behaviors, or unrelated economic shocks differentially affecting C- and S-corps at the

same time as TCJA.

Our goal of assesssing the efficiency impacts and distributional effects of TCJA’s corporate tax

cuts will require that we obtain elasticities of profits, investment, and earnings with respect to

the net-of-tax rate. To estimate these key elasticities, we pool outcomes in the post-period and

use two-stage least squares. The reduced form, first-stage, and structural equations are given,

respectively, by:

16

y

ft

= λC

f

∗ P ost

t

+ γ

f

+ α

is(f ),t

+

ft

(2)

ln(1 − ∆τ

f

) ∗ P ost

t

= δC

f

∗ P ost + γ

f

+ α

is(f ),t

+

ft

(3)

y

ft

= ε ln(1 − ∆τ

f

) ∗ P ost

t

+ γ

f

+ α

is(f ),t

+

ft

(4)

where ∆τ

f

is the 2016 to 2019 change in the marginal income tax rate for firm f , P ost

t

is

an indicator equal to 1 for years after 2018, and the fixed effects are the same as in equation 1.

Intuitively, we instrument for firms’ net-of-tax change using their pre-existing entity type status as

a C-or S-corps. The identifying assumptions underlying this empirical strategy are well known:

exogeneity, relevance, monotoncity, and exclusion. We do not claim strict exogeneity in our setting

– that is, we do not claim there is random assignment of C or S status – but rather rely on the

weaker claim of parallel trends in the outcome absent the changes in the tax rate (see Conley,

Hansen, and Rossi 2012). We examine the relevance and monotoncity conditions below, and return

to a discussion of the exclusion restriction when we evaluate mechanisms.

We begin the empirical analysis with a presentation of average responses, and then turn to

heterogeneity tests and robustness checks. We conclude the empirical analysis with a discussion

of mechanisms, where the focus is naturally related to the task of disentangling the impacts of

TCJA’s marginal tax rate cuts from other concurrent policy changes. First, however, our goal is

more modest: to provide clear evidence on how TCJA differentially affected C- and S-corps.

4.2 Marginal Tax Rates and Taxes Paid

Figure 3 plots the β

t

coefficients and 95% confidence intervals from estimating equation 1, using

the firms’ marginal tax rates and taxes paid as outcomes. We scale taxes paid (and other outcomes

that we will report below) by the firm’s baseline 2016 sales for the reasons discussed in Section 3.3.

In the bottom of each left panel we also report the 2016 sample outcome mean to contextualize the

economic scale and significance of the estimated coefficients.

Panel A of Figure 3 shows that the observed marginal tax rates of C- and S-corps trended

similarly prior to TCJA, but diverged sharply thereafter. On average, the marginal tax rate of

C-corps fell by approximately -5.2 percentage points (s.e.=0.2) compared to S-corps in the sample;

relative to the 2016 outcome mean in levels of 0.25, this represents a -5.2/0.25 ≈ 20.8% decline in

the marginal tax rate facing C-corps relative to S-corps. The panel also makes clear that firms’ tax

burdens began to decline in 2017, even though the bulk of TCJA’s provisions did not take effect

until 2018. This pattern provides suggestive evidence that firms engaged in intertemporal shifting

behaviors to minimize tax liability, such as reporting costs in 2017 rather than 2018 so that those

costs could be deducted at a higher tax rate. We discuss shifting behaviors in greater detail later in

Section 4.8.

Panel B of Figure 3 shows an analogous version of Panel A, where the outcome is transformed

as the log net-of-tax rate, (1-τ

MT R

f

). We show this transformation because economic theory predicts

17

FIGURE 3: EVENT STUDIES: MARGINAL TAX RATES AND TAXES PAID

Panel A: Marginal Tax Rate Panel B: Log Net-of-Tax Rate

-.06

-.04

-.02

0

.02

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.25

Marginal Tax Rate

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

0

.02

.04

.06

.08

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: -0.31

Log Net-of-Tax Rate

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Panel C: Tax / 2016 Sales Panel D: Tax Per Worker

-.02

-.01

0

.01

.02

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.06

Federal Tax

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

($)

-4,000

-3,000

-2,000

-1,000

0

1,000

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 6,045

Tax Per Worker

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Notes: The unit of analysis is a firm-year. The panels plot the β

t

coefficients estimated from equation 1. These coefficients capture

average differences in outcomes between C- and S-corps over time after controlling for firm and industry-size-year fixed effects.

Standard errors are clustered by firm and error bands show 95% confidence intervals. The outcome in Panel A is the firm’s marginal

tax rate, τ

MT R

f

, and the outcome in Panel B is the log net-of-tax rate, ln(1 − τ

MT R

f

). The outcome in Panel C is tax per worker,

reported in dollars, and the outcome in Panel D is tax scaled by the firms’ baseline 2016 sales. Marginal tax rates for S-corps are

defined as the weighted average of the shareholders’ individual marginal tax rates, where the weights are given by the ownership

shares. See Section 3 for details on the measurement of tax payments for S-corps. For data sources and variable definitions see Section

3.

18

that firms respond to the net-of-tax rate when optimizing profits. The figure shows that, on

average, C-corps saw their net-of-tax rate increase by approximately 6.8% (s.e.=0.2) relative to

S-corps following TCJA. Below, we use this result to scale other reduced form effects, allowing us

to estimate elasticities of key outcomes with respect to changes in the log net-of-tax rate.

Panel C of Figure 3 shows that the differences in tax cuts also translated into differences in

taxes paid, with C-corps paying approximately -1.0 percentage points (≈15.0%; s.e.=0.3) less in

federal tax in 2019 relative to their baseline sales when compared to S-corps. Panel D illustrates

that the magnitude of this effect is economically large: on average, C-corps paid approximately

$2,200 (s.e.=$436) less in tax per worker than comparable S-corps following TCJA.

Columns 1 to 4 of Table 2 report the C × P ost estimates produced from estimating equation

2. Similar to the event studies, these coefficients capture the average difference between

C- and S-corps in the pre- and post-periods for each outcome after controlling for firm and

industry-size-year fixed effects.

TABLE 2: MARGINAL TAX RATES AND TAXES PAID

(1) (2) (3) (4)

τ

MT R

f

ln(1 − τ

MT R

f

) Tax Per Worker Tax/Sales

2016

C × Post -0.052

∗∗∗

0.068

∗∗∗

-2203

∗∗∗

-0.010

∗∗∗

(0.002) (0.002) (436) (0.003)

2016 Outcome Mean 0.25 -0.31 6,045 0.06

Firm FE Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry-Size-Year FE Yes Yes Yes Yes

R2 0.72 0.73 0.59 0.83

N 81,529 81,529 81,529 81,529

N Firms 11,647 11,647 11,647 11,647

Notes: The unit of analysis is a firm-year. The table shows the C × P ost coefficients from

equation 2. These coefficients estimate average differential changes in outcomes between

C- and S-corps before and after TCJA, controlling for firm and industry-size-year fixed

effects. The outcome in column 1 is the firm’s marginal tax rate, τ

MT R

f

, and the outcome

in column 2 is the log net-of-tax rate, ln(1 − τ

MT R

f

). The outcome in column 3 is tax

per worker, reported in nominal dollars, and the outcome in column 4 is tax scaled by

the firms’ baseline 2016 sales. Marginal tax rates for S-corps are defined as the weighted

average of the shareholders’ individual marginal tax rates, where the weights are given by

the ownership shares. See Section 3 for details on the measurement of tax payments for

S-corps. Standard errors are clustered by firm.

The results in Figure 3 and Table 2 provide evidence of a strong first stage, demonstrating

an economically meaningful and statistically powerful differential effect of TCJA on the tax rates

and tax payments of C-corps versus S- corps. These results also show that the relevance and

monotoncity assumptions underlying equation 3 are satisfied in this setting.

19

4.3 Sales, Costs, Pre-Tax Profits, and EBITDA

Figure 4 plots the results from estimating equation 1 to assess trends in the sales, costs, and pre-tax

profits, and EBITDA of C- and S-corps over time. The figure shows trends in these outcomes

were statistically similar before TCJA, again lending support to the parallel trends assumption

underlying the identification strategy. After TCJA, however, C-corps’ sales increased markedly

relative to S-corps, by approximately 3.6 percentage points (s.e.=1.5) by 2019. The effect is precisely

estimated and economically significant: using values from Table 1, the coefficient implies that the

average C-corp increased its sales by approximately $40 million relative to comparable S-corps.

C-corps also faced higher costs, as shown in Panel B, although the magnitude of the cost

increase is smaller than for sales and, on average, is not statistically significant. Later we show

that this average effect masks important heterogeneity, with both sales and costs increasing

predominantly in capital intensive industries.

Given sharply increasing sales and only modestly increasing costs, Panel C shows that the

average pre-tax profits of C-corps also increased relative to S-corps, by 2.6 percentage points

(s.e.=0.9). Panel D shows an alternate measure of pre-tax profits, using the harmonized EBITDA

measure, and again reveals a clear increase in the profits of C-corps relative to S-corps. These

results provide initial evidence that firms expanded in response to tax cuts, consistent with the

standard notion that taxes induce economic distortions and may generate deadweight loss.

Columns 1 to 4 of Table 3 show the C × P ost coefficients associated with the event studies in

Figure 4. In column 5, we estimate the elasticity of pre-tax profits with respect to the net-of-tax rate

using equation 4. Scaling the reduced form estimate in column 3 by the first-stage estimate from

column 2 of Table 2 yields an elasticity of 0.38 (s.e.= 0.13).

This elasticity – known as the elasticity of the tax base, or alternately as the elasticity of taxable

income (ETI) – is a key parameter in the analysis. As shown by Feldstein (1999) and reviewed by

Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz (2012), under plausible assumptions it is a sufficient statistic that can be

used to estimate the welfare impacts and efficiency costs of tax changes. In general, a larger taxable

income elasticity implies greater deadweight loss, since it implies a larger distortion of economic

activity resulting from the tax.

Our estimate of the federal corporate ETI, 0.38, is on the lower end of corporate elasticities

identified from policy variation in small open economies. For example, Giroud and Rauh (2019)

estimate an elasticity of establishment growth (a proxy for the tax base) of approximately 0.50

with respect to state corporate taxes in the United States; Suárez Serrato and Zidar (2016) estimate

an elasticity of establishment growth of aproximately 0.9 for U.S. state corporate taxes over

an analogous time horizon to ours; and Bachas and Soto (2021) estimate large taxable income

elasticities of 3.0-5.0 for small firms in Costa Rica. On the other hand, our estimate of the corporate

ETI is on the higher end of most existing estimates of the ETI for personal incomes, which Saez,

Slemrod, and Giertz (2012) find in a literature review ranges from approximately 0.14 to 0.40, with

a central estimate of 0.25.

Viewed in the context of other research, we view our corporate ETI estimate as consistent with

20

FIGURE 4: EVENT STUDY: FIRM SALES, COSTS, AND PRE-TAX PROFITS

Panel A: Sales Panel B: Costs

-.02

0

.02

.04

.06

.08

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 1.00

Sales / 2016 Sales

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

-.02

-.01

0

.01

.02

.03

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.53

Costs / 2016 Sales

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Panel C: Pre-Tax Profits Panel D: EBITDA

-.02

0

.02

.04

.06

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.47

Pre-Tax Profits / 2016 Sales

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

-.05

0

.05

.1

.15

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.29

EBITDA / 2016 Sales

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Notes: Unit of analysis is firm-year. The panels plot the β

t

coefficients estimated from equation 1. These coefficients capture average

differences in outcomes between C- and S-corps over time after controlling for firm and industry-size-year fixed effects. Standard

errors are clustered by firm, and error bands show 95% confidence intervals. Sales are gross receipts. Costs are equal to cost of goods

sold, including both material and labor costs. Pre-tax profits are sales minus costs. EBITDA is a harmonized measure of earnings

before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amoritization; see Section 3 and Appendix B for details.

21

the common economic intuition that tax distortions vary with factor mobility. Firms and workers

are less mobile at the federal level than at the state and local level, mitigating distortions from

the federal corporate tax relative to the state and local corporate tax. However, many forms of

capital are internationally mobile relative to workers (Kotlikoff and Summers 1987), suggesting

that federal taxes on labor income, the primary source of personal income tax revenue, may be less

distorative than the federal corporate tax.

In Section 4.8 we perform extensive robustness checks on our ETI estimate, and in Section 6 we

discuss its significance in the context of the broader national tax and transfer system.

TABLE 3: SALES, COSTS, AND PRE-TAX PROFITS

(1) (2) (3) (4) (5)

Sales Costs Pre-tax π EBITDA Pre-tax π

C × Post 0.036

∗∗

0.010 0.026

∗∗∗

0.080

∗∗∗

(0.015) (0.009) (0.009) (0.011)

∆ ln(1 − τ

f

)× Post 0.379

∗∗∗

(0.127)

2016 Outcome Mean 1.00 0.53 0.47 0.29 0.47

Firm FE Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry-Size-Year FE Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes

R2 0.40 0.65 0.62 0.84 n.a.

N 81,529 81,529 81,529 81,529 81,529

N Firms 11,647 11,647 11,647 11,647 11,647

First-Stage F 409.5

Notes: The unit of analysis is a firm-year. Columns 1-4 show the C × P ost

coefficients from equation 2. These coefficients estimate average differential

changes in outcomes between C- and S-corps before and after TCJA, controlling

for firm and industry-size-year fixed effects. All outcomes are scaled by 2016

baseline sales. Sales are gross receipts. Costs are equal to cost of goods sold,

including both material and labor costs. Pre-tax profits are sales minus costs.

EBITDA is a harmonized measure of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation,

and amoritization. Column 5 reports the elasticity of pre-tax profits with respect

to the net-of-tax rate, computed by scaling the reduced form outcome in column

3 by the first stage coefficient from column 2 of Table 2. Standard errors are

clustered by firm. For additional information on data sources and variable

definitions see Section 3 and Appendix B.

4.4 After-Tax Profits and Shareholder Payouts

We use the same empirical strategy to evaluate trends in firms’ after-tax profits and payouts to

shareholders. Consistent with the increases in pre-tax profits and decline in tax liability, Panel A of

Figure 5, and Column 1 of Table 4, shows that the after-tax profits of C-corps increased relative to

S-corps following TCJA, by 3.6 percentage points (≈10.7%; s.e.=0.9). The magnitude of this effect is

22

economically and statistically signficiant, and underscores that tax cuts are highly lucrative to firm

owners. The elasticity of after-tax profits with respect to the net-of-tax rate, estimated in column

4 of Table 4 using equation 4, is 0.52 (s.e.= 0.13). Later, we leverage this elasticity to assess the

incidence of TCJA’s tax cuts on firm owners.

We also find that firms returned some of these excess profits to their shareholders via dividends

and share buybacks, the sum of which we refer to as total shareholders payouts. Because

shareholder payouts are infrequent events (approximately half of the payout observations in our

sample are zero), we study both the extensive and intensive margins. The outcome in Panel B of

Figure 5 is equal to one if total payouts are greater than zero (that is, the extensive margin), and

shows an increase of 4.0 percentage points (s.e.=0.8) in the payout probability of C-corps relative

to S-corps following TCJA. In Panel C we show the intensive margin, where the outcome is log

total payouts, and find that payouts of C-corps relative to S-corps increase by 21.9% (s.e.=5.0).

Consistent with this increase in shareholder payouts, in Appendix C.1 we find that C-corps do not

increase their issuance of equity or debt relative to S-corps after TCJA. The results are consistent

because, if firms need external financing to fund operations, they generally do not simulatenously

distribute cash to shareholders.

Overall, the results from Figure 5 and Table 4 provide evidence that firm owners bear a

substantial portion of the short-run economic incidence of the corporate income tax.

4.5 Labor Market Outcomes and Executive Pay

We again use equation 1 to examine the labor market outcomes of workers at C- and S-corps

before and after TCJA. Figure 6 shows the results from estimating equation 1 to assess trends in

log employment, total payroll, and annual earnings for selected groups of workers.

Figure 6 shows that the labor market outcomes of C- and S-corps followed similar trends prior

to TCJA. After TCJA, employment in C-corps increased modestly relative to S-corps, by 0.4%

(s.e.=0.8) on average, but the difference is not statistically distinguishable from zero. Total payrolls,

shown in Panel B, also increased modestly in C-corps relative to S-corps, by 1.2% (s.e.=0.8), and

again the difference is not statistically significant. However, later we show that these average

effects mask important heterogeneity across firms.

Panels C and D move beyond total payrolls to shed light on the distributional impacts of TCJA

on workers’ earnings. Panel C shows that the earnings of the median worker at the firm evolved

similarly for both C- and S-corps over the entire sample period, and implies that corporate tax

cuts did not have a statistically significant effect on earnings for the typical worker. By contrast,

Panels D shows that the earnings of higher-income C-corp workers increased sharply relative to

their counterparts in S-corps.

To more comprehensively evaluate the effects of TCJA on the distribution of workers’ earnings,

we estimate quantile regression specifications of equation 1, where the outcome y

ft

(p) is log annual

earnings of workers in firm f and year t at centile p. For example, y

ft

(p = 50) uses log median

earnings as the outcome, as shown in Panel C of Figure 6, and y

ft

(p = 99) uses the 99th percentile

23

FIGURE 5: EVENT STUDY: AFTER-TAX PROFITS AND SHAREHOLDER PAYOUTS

Panel A: After-Tax Profits

-.02

0

.02

.04

.06

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.41

After-Tax Profits / 2016 Sales

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Panel B: Shareholder Payouts (Extensive Margin)

-.02

0

.02

.04

.06

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 0.54

Shareholder Payouts (0/1)

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Panel C: Shareholder Payouts (Intensive Margin)

-.1

0

.1

.2

.3

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

2016 Outcome Mean: 1.45

Log Shareholder Payouts

Difference Between C-Corps and S-Corps Over Time

Notes: The unit of analysis is a firm-year. The panels plot the β

t

coefficients estimated from equation 1. These coefficients capture

average differences in outcomes between C- and S-corps over time after controlling for firm and industry-size-year fixed effects.

Standard errors are clustered by firm and error bands show 95% confidence intervals. In Panel A, after-tax profits are defined as

pre-tax profits minus tax, and are scaled by 2016 baseline sales. In Panel B, the outcome is an indicator equal to 1 if shareholder

payouts are positive (i.e., the extensive margin), where payouts are defined as the sum of cash and property distributions to

shareholders. In Panel C, the outcome is log shareholder payouts (i.e., the intensive margin). For additional information on data

sources and variable definitions see Section 3 and Appendix B.

24

TABLE 4: AFTER-TAX PROFITS AND SHAREHOLDER PAYOUTS

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Post-Tax π Payouts (0/1) Log Payouts Post-Tax π

C × Post 0.036

∗∗∗

0.034

∗∗∗

0.246

∗∗∗

(0.009) (0.006) (0.034)

∆ ln(1 − τ

f

)× Post 0.521

∗∗∗

(0.129)

2016 Outcome Mean 0.41 0.54 1.45 0.41

Firm FE Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry-Size-Year FE Yes Yes Yes Yes

R2 0.69 0.76 0.86 n.a.

N 81,529 81,529 81,529 81,529

N Firms 11,647 11,647 11,647 11,647

First-Stage F 409.5

Notes: The unit of analysis is firm-year. Columns 1-3 show the C × P ost

coefficients from equation 2. These coefficients estimate average differential changes

in outcomes between C- and S-corps before and after TCJA, controlling for firm and

industry-size-year fixed effects. After-tax profits are defined as pre-tax profits minus

tax, and are scaled by 2016 baseline sales. In column 2, the outcome is an indicator

equal to 1 if shareholder payouts are positive (i.e., the extensive margin), where

payouts are defined as the sum of cash and property distributions to shareholders. In

column 3 the outcome is log shareholder payouts (i.e., the intensive margin). Column

4 reports the elasticity of after-tax profits with respect to the net-of-tax rate, computed

as in equation 4. Standard errors are clustered by firm. For additional information on

data sources and variable definitions see Section 3 and Appendix B.

25

of log worker earnings as the outcome, as in Panel D.

Figure 7 plots the β

2019

coefficients from these quantile regressions along with their

corresponding 95% confidence invervals. The figure shows that the relative earnings of workers

in C- and S-corps below the 90th percentile are statistically identical following TCJA; we cannot

reject that the coefficients are statistically distinguishable from zero.

However, Figure 7 reveals a very different pattern for workers in the top 10% of the earnings

distribution. Workers in C-corps at the 90th percentile of the within-firm distribution see their

relative earnings increase by 1.0% (s.e.=0.3), and these impacts grow steadily larger and statistically

sharper further up the distribution. At the 95th percentile, we estimate a relative earnings increase

of 1.2% (s.e.=0.4) for C-corp workers, and this magnitude climbs to 4.5% (s.e.=0.8) at the 99th

percentile.

We further assess the impacts of MTR cuts on executive pay. Figure 8 estimates equation 1 using

as outcomes log officer compensation (observed on IRS Forms 1120 and 1120s) and a proxy variable

constructed as the log mean earnings of the top five highest-paid workers at the firm (observed

from IRS Form W2). In Panel A, we estimate that the relative earnings of executives increased

by 4.6% (s.e.=1.2) at C-corps relative to S-corps, and in Panel B we estimate a quantitatively

comparable effect for the earnings of the top 5 highest paid workers at the firm of 4.0% (s.e.=0.8).

Because the tax data do not allow us to observe all components of executive compensation, such

as awarded bu unvested stock grants, these estimates likely represent a lower bound on the effects

of TCJA on executive pay. The fact that executive earnings increase in 2017, before TCJA fully took

effect, is consistent with firms intertemporally shifting forward executive compensation, perhaps

in the form of bonuses, so that these costs could be deducted at a higher tax rate prior to the

corporate rate cut beginning in 2018.

Panel A of Table 5 reports the C × P ost coefficients from equation 2, as well as the dependent

variable means in the baseline year and implied elaticities with respect to the net-of-tax rate. For

workers at the 95th percentile, we estimate an earnings elasticity of 0.18% (s.e.=0.05), and for

executives we estimate a larger earnings elasticity of 0.64% (s.e.=0.17). The mean baseline earnings