Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

For use at 11:00 a.m. EDT

July 5, 2024

Monetary Policy rePort

July 5, 2024

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., July 5, 2024

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chair

statement on Longer-run goaLs and monetary PoLicy strategy

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as reafrmed effective January30, 2024

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory mandate from

the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate long-term interest rates. The

Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public as clearly as possible. Such clarity

facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and businesses, reduces economic and nancial

uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary policy, and enhances transparency and accountability,

which are essential in a democratic society.

Employment, ination, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and nancial

disturbances. Monetary policy plays an important role in stabilizing the economy in response to these

disturbances. The Committee’s primary means of adjusting the stance of monetary policy is through changes

in the target range for the federal funds rate. The Committee judges that the level of the federal funds rate

consistent with maximum employment and price stability over the longer run has declined relative to its

historical average. Therefore, the federal funds rate is likely to be constrained by its eective lower bound

more frequently than in the past. Owing in part to the proximity of interest rates to the eective lower bound,

the Committee judges that downward risks to employment and ination have increased. The Committee is

prepared to use its full range of tools to achieve its maximum employment and price stability goals.

The maximum level of employment is a broad-based and inclusive goal that is not directly measurable

and changes over time owing largely to nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the

labor market. Consequently, it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the

Committee’s policy decisions must be informed by assessments of the shortfalls of employment from its

maximum level, recognizing that such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The

Committee considers a wide range of indicators in making these assessments.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the Committee

has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its judgment that ination

at the rate of 2percent, as measured by the annual change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The

Committee judges that longer-term ination expectations that are well anchored at 2percent foster price

stability and moderate long-term interest rates and enhance the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. In order to anchor longer-term ination

expectations at this level, the Committee seeks to achieve ination that averages 2percent over time, and

therefore judges that, following periods when ination has been running persistently below 2percent,

appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve ination moderately above 2percent for some time.

Monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity, employment, and prices with a lag. In setting

monetary policy, the Committee seeks over time to mitigate shortfalls of employment from the Committee’s

assessment of its maximum level and deviations of ination from its longer-run goal. Moreover, sustainably

achieving maximum employment and price stability depends on a stable nancial system. Therefore, the

Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-term outlook, and its assessments of

the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that could impede the attainment of the

Committee’s goals.

The Committee’s employment and ination objectives are generally complementary. However, under

circumstances in which the Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it takes into account

the employment shortfalls and ination deviations and the potentially dierent time horizons over which

employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to review these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its annual

organizational meeting each January, and to undertake roughly every 5years a thorough public review of its

monetary policy strategy, tools, and communication practices.

Summary .................................................................1

Recent Economic and Financial Developments ................................... 1

Monetary Policy ........................................................... 3

Special Topics ............................................................. 3

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments .....................5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments .................................................... 30

International Developments ................................................. 36

Part 2: Monetary Policy ..................................................41

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections ................................53

Abbreviations ............................................................71

contents

contents

Note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of noon EDT on July2, 2024.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, June28, 2024; for monthly data,

May2024; and, for quarterly data, 2024:Q1. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a given period is measured to

its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 26, 37, and 43, note that the S&P/Case-Shiller U.S. National Home Price Index, the S&P 500 Index, and the Dow Jones Bank Index are

products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and have been licensed for use by the Board. Copyright © 2024 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a

division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All rights reserved. Redistribution, reproduction, and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without

written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices, please visit www.spdji.com.

S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial Services LLC, and Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings

LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates, nor their third-party licensors make any representation or

warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither

S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC, their afliates, nor their third-party licensors shall have any liability for any errors, omis-

sions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

List of Boxes

Housing Services Ination and Market Rent Measures .............................. 9

Employment and Earnings across Demographic Groups ............................ 16

Developments Related to Financial Stability ..................................... 33

Monetary Policy Independence, Transparency, and Accountability .................... 42

Developments in the Federal Reserve’s Balance Sheet and Money Markets .............. 47

Monetary Policy Rules in the Current Environment ................................ 50

Forecast Uncertainty ....................................................... 68

1

Ination eased notably last year and has

shown modest further progress so far this

year, but it remains above the Federal Open

Market Committee’s (FOMC) objective of

2percent. Job gains have been strong, and the

unemployment rate is still low. Meanwhile, as

job vacancies continued to decline and labor

supply continued to increase, the labor market

moved into better balance over the rst half of

the year. Real gross domestic product (GDP)

growth was modest in the rst quarter, while

growth in private domestic demand remained

robust, supported by slower but still-solid

increases in consumer spending, moderate

growth in capital spending, and a sharp pickup

in residential investment.

The FOMC has maintained the target range

for the federal funds rate at 5¼ to 5½percent

since its July2023 meeting. In addition,

the Committee has continued to reduce its

holdings of Treasury securities and agency

mortgage-backed securities. The Committee

does not expect it will be appropriate to

reduce the target range until it has gained

greater condence that ination is moving

sustainably toward 2percent. Reducing policy

restraint too soon or too much could result in

a reversal of the progress on ination. At the

same time, reducing policy restraint too late

or too little could unduly weaken economic

activity and employment. In considering any

adjustments to the target range for the federal

funds rate, the Committee will carefully assess

incoming data, the evolving outlook, and the

balance of risks.

The FOMC is strongly committed to

returning ination to its 2percent objective.

The Committee remains highly attentive

to ination risks and is acutely aware that

high ination imposes signicant hardship,

especially on those least able to meet the higher

costs of essentials.

Recent Economic and Financial

Developments

Ination. Although personal consumption

expenditures (PCE) price ination slowed

notably last year and has shown modest

further progress this year, it remains above the

FOMC’s longer-run objective of 2percent.

The PCE price index rose 2.6percent over

the 12months ending in May, down from the

4.0percent pace over the preceding 12 months

and a peak of 7.1percent in June2022.

The core PCE price index—which excludes

food and energy prices and is generally

considered a better guide to the direction

of future ination—also rose 2.6percent in

the 12months ending in May, down from

4.7percent a year ago and slower than the

2.9percent pace at the end of last year. On a

12-month basis, core goods price ination and

housing services price ination continued to

ease over the rst part of the year, while core

nonhousing services price ination attened

out after slowing notably last year. Measures

of longer-term ination expectations are

within the range of values seen in the decade

before the pandemic and continue to be

broadly consistent with the FOMC’s longer-

run objective of 2percent.

The labor market. The labor market continued

to rebalance over the rst half of this year,

and it remained strong. Job gains were solid,

averaging 248,000 per month over the rst ve

months of the year, and the unemployment

rate remained low. Labor demand has eased, as

job openings have declined in many sectors of

the economy, and labor supply has continued

to increase, supported by a strong pace of

immigration. With cooling labor demand and

rising labor supply, the unemployment rate

edged up to 4.0percent in May. The balance

between labor demand and supply appears

similar to that in the period immediately

summary

2 SUMMARY

before the pandemic, when the labor market

was relatively tight but not overheated.

Nominal wage growth continued to slow in

the rst part of the year but remains above a

pace consistent with 2percent ination over

the longer term, given prevailing trends in

productivity growth.

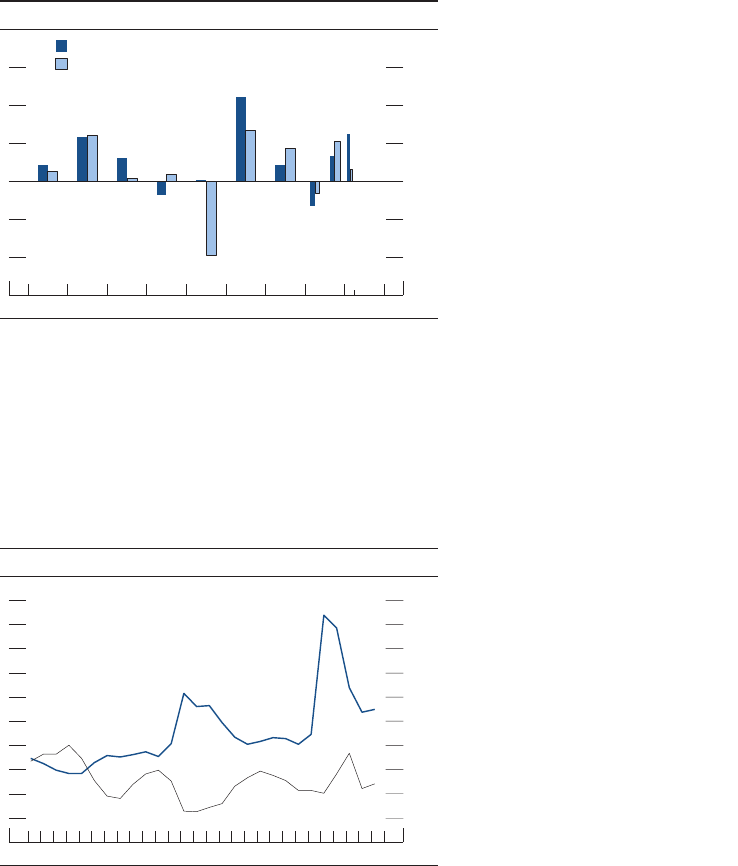

Economic activity. Real GDP growth is

reported to have moderated in the rst

quarter after having increased at a robust

pace in the second half of last year. Much

of the slowdown was due to sizable drags

in the volatile categories of net exports and

inventory investment; growth in private

domestic nal purchases—which includes

consumer spending, business xed investment,

and residential investment—also moved a

little lower in the rst quarter but remained

solid. Real consumption growth slowed in the

rst quarter from a strong pace in the second

half of last year, reecting a decline in goods

spending. Real business xed investment

grew at a moderate pace in the rst quarter

despite high interest rates, supported by strong

sales growth and improvements in business

sentiment and prot expectations. Activity in

the housing sector picked up sharply in the

rst quarter as a result of a jump in existing

home sales and rising construction of single-

family homes.

Financial conditions. Financial conditions

appear somewhat restrictive on balance.

Treasury yields and the market-implied

expected path of the federal funds rate have

moved up, on net, since the beginning of

the year, while broad equity prices have

increased. Credit remains generally available

to most households and businesses but at

elevated interest rates, which have weighed on

nancing activity. The pace of bank lending

to households and businesses increased in the

rst ve months of the year but continues

to be somewhat tepid. Delinquency rates on

small business loans stayed slightly above

pre-pandemic levels, and delinquency rates for

credit cards, auto loans, and commercial real

estate loans continued to increase in the rst

quarter of 2024 to levels above their longer-

run averages.

Financial stability. The nancial system

remains sound and resilient. The balance

sheets of nonnancial businesses and

households stayed strong, with the combined

credit-to-GDP ratio standing near its two-

decade low. Business debt continued to decline

in real terms, and debt-servicing capacity

remained solid for most public rms, in

large part due to strong earnings, large cash

buers, and low borrowing costs on existing

debt. However, there were also signs of

vulnerabilities building in the nancial system.

In asset markets, corporate bond spreads

narrowed, equity prices rose faster than

expected earnings, and residential property

prices remained high relative to market rents.

Moreover, in the banking sector, some banks’

fair value losses on xed-rate assets remained

sizable, despite most of them continuing to

report solid capital levels. Additionally, parts

of banks’ commercial real estate portfolios

are facing stress. Some banks’ reliance on

uninsured deposits remained high. Even so,

liquidity at most domestic banks remained

ample, with limited reliance on short-term

wholesale funding. Bond mutual funds’

exposure to interest rate risk stayed elevated,

and data through the third quarter of 2023

show that hedge fund leverage had grown to

historical highs, driven primarily by borrowing

by the largest hedge funds. (See the box

“Developments Related to Financial Stability”

in Part 1.)

International developments. Foreign economic

activity appears to have improved in the rst

quarter after a soft patch in the second half

of last year. In advanced foreign economies,

growth rates returned to moderate levels

despite the eects of restrictive monetary

policy as lower ination improved real

household incomes. In emerging market

economies, growth was supported by a

recovery in exports and rising global demand

for high-tech products, with the rise in activity

in China in the rst quarter being particularly

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 3

outsized. Nonetheless, other factors continued

to weigh on economic growth: Data indicated

ongoing weakness in China’s property sector,

and in Europe, energy-intensive sectors

continue to struggle, reecting their ongoing

adjustment to past increases in energy prices

following Russia’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine.

Foreign headline ination has continued to

decline since the middle of last year, but the

pace of disination has been gradual and

uneven across countries and economic sectors.

Still, many foreign central banks have noted

this progress in lowering ination, and some

have begun to cut their policy rates. A notable

exception is Japan, which ended its negative

interest rate policy and yield curve control in

March amid persistently high ination. The

trade-weighted exchange value of the dollar

rose signicantly, consistent with widening

gaps between U.S. and foreign interest rates.

Monetary Policy

Interest rate policy. The FOMC has

maintained the target range for the policy

rate at 5¼ to 5½percent since its July2023

meeting. The Committee judges that the risks

to achieving its employment and ination

goals have moved toward better balance

over the past year. The Committee perceives

the economic outlook to be uncertain

and remains highly attentive to ination

risks. The Committee has indicated that

it does not expect it will be appropriate to

reduce the target range until it has gained

greater condence that ination is moving

sustainably toward 2percent. Policy is

well positioned todeal with the risks and

uncertainties the Committee faces in pursuing

both sides of its dual mandate. In considering

any adjustments to the target range for

the federal funds rate, the Committee will

carefully assess incoming data, the evolving

outlook, and the balance of risks.

Balance sheet policy. The Federal Reserve

has continued the process of signicantly

reducing its holdings of Treasury and agency

securities in a predictable manner.

1

Beginning

in June2022, principal payments from

securities held in the System Open Market

Account have been reinvested only to the

extent that they exceeded monthly caps. Under

this policy, the Federal Reserve has reduced

its securities holdings about $1.7trillion since

the start of balance sheet reduction. The

FOMC has stated that it intends to maintain

securities holdings at amounts consistent with

implementing monetary policy eciently and

eectively in its ample-reserves regime. To

ensure a smooth transition from abundant to

ample reserve balances, the FOMC slowed

the pace of decline of its securities holdings

at the beginning of June and intends to

stop reductions when reserve balances are

somewhat above the level that the Committee

judges to be consistent with ample reserves.

Special Topics

Housing services ination. The PCE price

index for housing services started accelerating

in 2021, notably increasing its contribution

to core PCE ination. Because this index

calculates average rent for all tenants—both

new tenants and existing tenants—its changes

tend to lag changes in market rent measures

for new leases. Therefore, measures of market

rent growth for new leases can help predict

future changes in the PCE price index. Since

mid-2022, market rents have decelerated

and returned to a growth rate similar to or

below their average pre-pandemic pace, while

the PCE index continues to show elevated

ination, reecting the gradual pass-through

of market rates to existing tenants. As this

process continues, PCE housing services

ination should gradually decline, though

much uncertainty remains about the extent

1. See the May4, 2022, press release regarding the

Plans for Reducing the Size of the Federal Reserve’s

Balance Sheet, available on the Board’s website at https://

www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/

monetary20220504b.htm.

4 SUMMARY

and timing. (See the box “Housing Services

Ination and Market Rent Measures”

in Part 1.)

Employment and earnings across groups. A

strong labor market over the past two years

has been especially benecial for historically

disadvantaged groups of workers. As a

result, many of the long-standing disparities

in employment and wages by sex, race,

ethnicity, and education have narrowed, and

some gaps reached historical lows in 2023

and the rst half of 2024. However, despite

this narrowing, signicant disparities in

absolute levels across groups remain. (See

the box “Employment and Earnings across

Demographic Groups” in Part 1.)

Monetary policy independence, transparency,

and accountability. Congress has established

a statutory framework that species the

long-run objectives of monetary policy—

maximum employment and stable prices—

and gives the Federal Reserve operational

independence in conducting monetary policy.

In this framework, the Federal Reserve

makes determinations about the monetary

policy actions that are most appropriate

for achieving the dual-mandate goals that

Congress has assigned to it. The Federal

Reserve recognizes that independence is

a trust given to it by Congress and the

American people and that with independence

comes the need to be transparent about,

and accountable for, its monetary policy

decisions. Transparency also improves

monetary policy’s eectiveness. The Federal

Reserve promotes transparency by providing

information about FOMC decisions through

policy communications and a variety of

publications. The means by which the Federal

Reserve informs the American people

about its monetary policy decisions include

ocial FOMC statements, monetary policy

reports, and Committee meeting minutes

and transcripts, as well as speeches, press

conferences, and congressional testimony

given by Federal Reserve ocials. (See

the box “Monetary Policy Independence,

Transparency, and Accountability” in Part 2.)

Federal Reserve’s balance sheet and money

markets. The size of the Federal Reserve’s

balance sheet has continued to decrease

since February as the FOMC has reduced

its securities holdings. Reserve balances, the

largest liability on the Federal Reserve’s balance

sheet, and usage of the overnight reverse

repurchase agreement facility—another Federal

Reserve liability—both declined. (See the

box “Developments in the Federal Reserve’s

Balance Sheet and Money Markets” in Part2.)

Monetary policy rules. Simple monetary policy

rules, which prescribe a setting for the policy

interest rate in response to the behavior of

a small number of economic variables, can

provide useful guidance to policymakers. With

ination easing over the past year, the policy

rate prescriptions of most simple monetary

policy rules have decreased recently and now

call for levels of the federal funds rate that are

close to or below the current target range for

the federal funds rate. (See the box “Monetary

Policy Rules in the Current Environment”

inPart2.)

5

Domestic Developments

Ination eased notably last year and

has shown modest further progress in

recentmonths

Ination stepped down markedly last year

and has shown modest further progress so

far this year. Ination remains elevated,

though, and is still above the Federal Open

Market Committee’s (FOMC) longer-run

objective of 2percent. The price index for

personal consumption expenditures (PCE)

rose 2.6percent over the 12 months ending in

May, down from the 4.0percent pace a year

ago but little changed since the end of last year

(gure1). After having slowed markedly in the

second half of 2023, monthly core PCE price

ination—which excludes food and energy

prices and is generally considered a better

guide to the direction of future ination—

rmed in the rst quarter of this year and

then eased somewhat in April and May. As a

result, the 12-month change in core PCE prices

declined from the 4.7percent pace in May

of last year to 2.9percent in December and

moved down further this year, to 2.6percent

in May (gure2). A similar message is

evident from the trimmed mean measure

of PCE prices constructed by the Federal

Reserve Bank of Dallas, which provides an

alternative approach to reducing the inuence

of idiosyncratic price movements. The index

increased 2.8percent over the 12months

ending in May, a pace that is somewhat slower

than at the end of last year (as shown in

gure1).

Consumer energy prices have

increased, while food price ination has

attenedout

PCE energy prices increased 4.8percent in the

12 months ending in May after having declined

12.3percent over the preceding 12 months

Part 1

recent economic and financiaL deveLoPments

Total

Excluding food and energy

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

1. Personal consumption expenditures price indexes

Monthly

SOURCE: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for a

ll

else, Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

Trimmed mean

6-month change

12-month change

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Percent, annual rate

20242023202220212020201920182017

2. Core personal consumption expenditures price index

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, personal consumption

expenditures via Haver Analytics.

3-month change

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

(gure3, left panel). Oil prices increased, on

net, in the rst half of this year (gure4).

Prices rose amid concerns about escalation

of the conict in the Middle East, additional

costs of rerouting some oil shipping away

from the Red Sea, and ongoing production

cuts by OPEC (Organization of the Petroleum

Exporting Countries) and its allies. Continuing

geopolitical tensions, including tensions

emanating from the conicts in the Middle

East and Ukraine, pose an upside risk to

energy prices.

Prices of agricultural commodities and

livestock edged up, on net, over the rst half

of this year after having come down markedly

in 2022 and 2023 from the highs reached at the

start of Russia’s war on Ukraine in early 2022

(gure5). As a result of these movements, the

12-month change in PCE food prices slowed

substantially from its peak of 12.2percent in

August2022 to just 1.2percent in May (as

shown in gure3, left panel).

Prices of both energy and food products are

of particular importance for lower-income

households, for which such necessities account

for a large share of expenditures. Reecting the

sharp increases seen in 2021 and 2022, these

price indexes are 25percent and 32percent

higher than in 2019, for food and energy,

respectively.

Food and

beverages

Services

ex. energy

and housing

Goods ex. food, beverages, and energy

20

10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

4

2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

Food and energy

Percent change from year earlier

Energy

+

–

+

–

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

Percent change from year earlier

20242023202220212020201920182017

Components of core prices

Monthly

Housing services

NOTE: The data are monthly.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

3. Subcomponents of personal consumption expenditures price indexes

Brent spot price

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

Dollars per barrel

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

4. Spot and futures prices for crude oil

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE

: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend through

June 28, 2024.

S

OURCE

: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

Agriculture

and livestock

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

Week ending January 4, 2019 = 100

2019 2020 2021 2022 2023 2024

5. Spot prices for commodities

Weekly

Industrial metals

N

OTE

: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend through

June 28, 2024.

S

OURCE

: For industrial metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Spot

Index; for agriculture and livestock, S&P GSCI Agriculture & Livestock

Spot Index; both via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 7

4

2

+

_

0

2

4

6

8

Percent change from year earlier

202420222020201820162014

6. Nonfuel import price index

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

Core goods prices increased modestly

this year after having declined sharply in

the second half of 2023

In assessing the outlook for ination, it is

helpful to consider three separate components

of core prices: core goods, housing services,

and core nonhousing services. After posting

notable declines in the second half of last

year, core goods prices increased modestly,

on net, over the rst months of this year. This

development likely reects, in part, movements

in nonfuel import prices, which turned up in

recent months after having declined, on net,

over 2023 (gure6). Smoothing through these

monthly movements, prices for core goods over

the 12 months ending in May moved down

1.1percent, similar to their pre-pandemic rate

of decline, after having increased 2.5percent

over the previous 12-month period (gure3,

right panel). The progress on ination for

core goods reects improvements in supply–

demand imbalances. Indeed, the supply chain

issues and other capacity constraints that had

earlier boosted ination so much continued

to ease, though at a more gradual pace this

year than over the past two years, and supply–

demand conditions in goods markets appear

to be relatively balanced. For example, the

shares of respondents to the Quarterly Survey

of Plant Capacity Utilization citing insucient

supply of labor or materials as reasons

for producing below capacity, which had

increased considerably during the pandemic,

have continued to fall and are now near pre-

pandemic levels (gure7).

Housing services price ination

continued to slow gradually but remains

elevated . . .

The 12-month change in housing services

prices moved down from more than 8percent

in May2023 to 5.5percent in May of this year

but is still well above its pre-pandemic level (as

shown in gure3, right panel). Market rent

ination, which measures increases in rents for

new housing leases to new tenants, has fallen

markedly since late 2022 to near pre-pandemic

rates, and this slowdown points to continued

easing of housing services ination over the

Insucient supply

of labor

0

10

20

30

40

50

Percent

202420232022202120202019

7. Reasons for operating below full capacity

Quarterly

Insucient supply

of materials

N

OTE: The series are the share of rms selecting each reason for

operating below full capacity.

S

OURCE: U.S. Census Bureau: Quarterly Survey of Plant Capacity

Utilization.

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

year ahead. (The box “Housing Services

Ination and Market Rent Measures” provides

further details.)

. . . while core nonhousing services price

ination attened out so far this year

Finally, price ination for core nonhousing

services—a broad group that includes services

such as travel and dining, nancial services,

and car repair—slowed last year but attened

out, on net, in the rst ve months of this

year. Core nonhousing services prices rose

3.4percent in the 12months ending in May,

down from 4.7percent a year ago but little

changed since the end of last year (as shown

in gure3, right panel). The lack of further

progress this year is due in large part to price

increases in volatile categories—for example,

portfolio management services, which can

be inuenced by idiosyncratic factors, such

as swings in the stock market, more than

supply and demand conditions. Because

labor is a signicant input to these service

sectors, the ongoing deceleration in labor

costs—supported by softening labor demand

and improvements in labor supply—suggests

that disination will eventually resume for

thiscategory.

Measures of longer-term ination

expectations have been stable; shorter-

term expectations have been volatile but

are generally lower than a year earlier

The generally held view among economists

and policymakers is that ination expectations

inuence actual ination by aecting wage-

and price-setting decisions. Survey-based

measures of expected ination over a longer

horizon have generally been moving sideways

over the past year, within the range seen during

the decade before the pandemic, and they

appear broadly consistent with the FOMC’s

longer-run 2percent ination objective. This

development is seen for surveys of households,

such as the University of Michigan Surveys

of Consumers, and for surveys of professional

forecasters (gure8). For example, the median

forecaster in the Survey of Professional

SPF, next 10 years

Michigan survey, next 5 to 10 years

SPF, 6 to 10 years ahead

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

4.5

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

Percent

20242022202020182016201420122010

8. Measures of ination expectations

N

OTE

: The data for the Michigan survey are monthly and extend

through June 2024. The Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF) data

are quarterly and extend through 2024:Q2.

S

OURCE

: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Federal

Reserve Bank of Philadelphia, SPF.

Michigan survey, next 12 months

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 9

(continued on next page)

units, they are typically smaller for continuing tenants

renewing their lease than they are for new tenants.

3

This lag implies that measures of rent growth for

new leases can help predict future changes in the

PCE price index for housing services. Over the past

few decades, private rms have started publishing

various “market rent” measures that track the average

rent for new leases by new tenants.

4

For example, the

3. See Ben Houck (2022), “Housing Leases in the

U.S. Rental Market,” Spotlight on Statistics (Washington:

Bureau of Labor Statistics, September), https://www.bls.gov/

spotlight/2022/housing-leases-in-the-u-s-rental-market/

home.htm.

4. PCE prices for housing services differ from these market

rent measures for reasons beyond the fact that market rent

measures are limited to new leases to new tenants. In addition,

the discrepancy arises from the methodology used for index

construction (for example, the rent measures used in the PCE

price index sample a given residence only once every six

months), the representativeness of the sample, and the way in

which the measure controls for quality adjustments. Moreover,

market rent measures capture the “asking” prices posted by

landlords, while the rent measures used in the PCE price index

gauge the rent that tenants actually pay. Among these factors,

whether all leases are used (as opposed to only new leases)

appears to be the main contributor to this discrepancy. See

Brian Adams, Lara Loewenstein, Hugh Montag, and Randal

Verbrugge (2024), “Disentangling Rent Index Differences:

Data, Methods, and Scope,” American Economic Review:

Insights, vol. 6 (June), pp. 230–45.

The price index for housing services includes rents

explicitly paid by renters as well as implicit rents that

homeowners would have to pay if they were renting

their homes known as owners’ equivalent rent (OER).

This index is an important component of the price

index for personal consumption expenditures (PCE),

composing about 15.5percent of the total PCE price

index. Housing services prices started accelerating

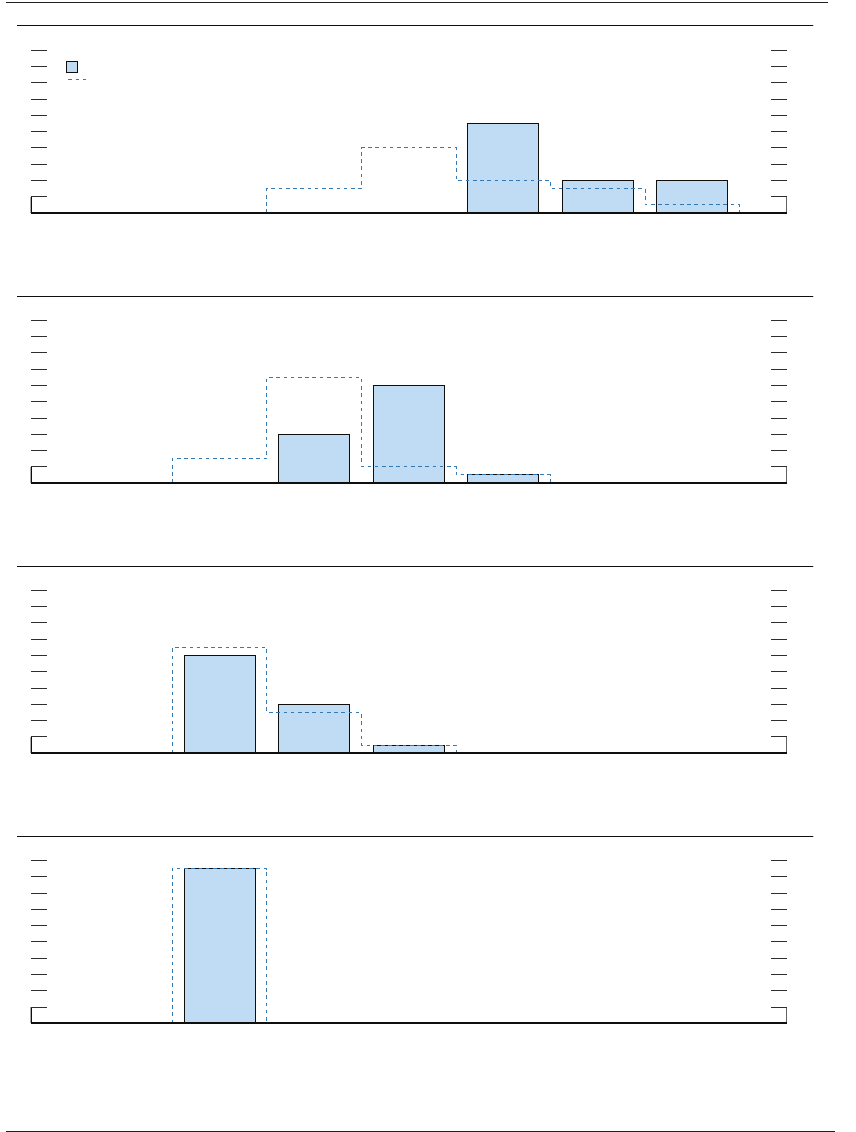

in 2021, and, as gure A illustrates, the contribution

of these prices to the 12-month change in the core

PCE price index increased notably, reaching a peak

of 1.4percentage points in 2023. In May2024, the

contribution of this component stood at 1.0percentage

point, down from its peak but still well above the

0.5percentage point that was typical before the

COVID-19 pandemic.

The PCE price index for housing services is derived

from two components of the consumer price index

(CPI): rent of primary residence and OER.

1

The rent of

primary residence index measures the average rent paid

by tenants. OER estimates the rent that homeowners

would pay if they were renting their homes without

furnishings or utilities and is derived from rental data

for units in the same neighborhood, with an adjustment

for structure type.

2

Because the price index for housing services

measures average rent for all tenants—both new

tenants and existing tenants—its changes are more

subdued and tend to lag changes in rent measures for

new leases, described later. Because rental agreements

typically last for 12months, most renters will not see an

immediate increase in their rent even if the rent for new

leases increases sharply. Additionally, the Bureau of

Labor Statistics, the agency responsible for computing

the CPI, reports that when rent increases occur for

1. The sum of the weights of these two components in the

total CPI is 34.4percent, considerably higher than their weight

in the total PCE price index.

2. The typical structure type varies signi cantly across

owner- and tenant-occupied units: Owner-occupied homes

are mostly single-family units, while renter-occupied homes

are roughly evenly divided between single-family and

multifamily units. Constructing the OER measure involves

reweighting the sample of rent quotes for a given area to

re ect the relative importance of owner-occupied housing in

that area. See slide13 of Robert Cage (2019), “Measurement

of Owner Occupied Housing in the U.S. Consumer Price

Index” (Washington: Bureau of Labor Statistics, November15),

https://www.bea.gov/system/files/2019-11/bea_tac_nov2019_

cage.pdf.

Housing Services In ation and Market Rent Measures

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percentage points

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

A. Contributions to 12-month change in core

personal consumption expenditures price index

Monthly

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics;

Federal

Reserve Board sta calculations.

Core goods

Core services ex. housing

Housing services

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Figure B illustrates that, historically, the year-over-

year change in market rents is an informative leading

indicator for the year-over-year change in PCE housing

multifamily apartment buildings. The Apartment List National

Rent Index, available beginning in 2017, measures changes in

median market rents across the entire rental market for both

single-family and multifamily units. To calculate unit-level rent

growth, all these measures, including the CoreLogic index,

use the repeat-rent methodology to control for differences

in property characteristics among the units listed for rent in

different periods.

CoreLogic Single-Family Rent Index measures changes

in average market rents for single-family homes.

Other measures include the Zillow, Apartment List,

and RealPage indexes, which vary in terms of the type

of unit they cover (single-family versus multifamily),

their methodologies, and the representativeness of the

national rental market.

5

5. The Zillow Observed Rent Index for single-family

residences, available beginning in 2015, focuses on changes

in asking rents for single-family units. The RealPage Rent

Index, available beginning in 1996, measures changes

in average market rents across professionally managed

Zillow single-family units

CoreLogic single-family detached units

RealPage multifamily units

6

3

+

_

0

3

6

9

12

15

18

21

Percent change from year earlier

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

B. Housing rents

Monthly

NOTE: CoreLogic data extend through April 2024, Zillow data start in January 2016, and Apartment List data start in January 2018 and e

xtend

through

June 2024. Zillow, CoreLogic, Apartment List, and RealPage measure market-rate rents—that is, rents for a new lease by a new tenant. PCE i

s

personal consumption expenditures.

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis, PCE, via Haver Analytics; CoreLogic, Inc.; Zillow, Inc.; Apartment List, Inc. via Haver Analytics; RealPage

,

Inc.; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

PCE housing services

Apartment List single-family and multifamily units

(continued)

Housing Services In ation (continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 11

contracts typically last for a year and rents for existing

tenants take some time to catch up to the rents charged

to new tenants. In particular, the rise in measures of

market rents, including the CoreLogic Single-Family

Rent Index and the Zillow Observed Rent Index, from

the onset of the pandemic until now has been larger

than the corresponding increase in the PCE price

index for housing services, suggesting that the PCE

price measure has not yet fully caught up with the

current state of the rental market.

8

However, as long

as market rents continue to increase moderately, PCE

housing services in ation should gradually decline

and eventually return to its pre-pandemic pace as well.

However, signi cant uncertainty remains regarding the

timing of this decline and whether market rent in ation

will, in fact, remain moderate.

8. Between January2020 and April 2024, the CoreLogic

Single-Family Rent Index and the Zillow Observed Rent Index

have increased 32 percent and 38 percent, respectively, while

PCE prices for housing services have increased 23percent.

See Christopher D. Cotton (2024), “A Faster Convergence of

Shelter Prices and Market Rent: Implications for In ation,”

Current Policy Perspectives 2024-4 (Boston: Federal Reserve

Bank of Boston, June), https://www.bostonfed.org/-/media/

Documents/Workingpapers/PDF/2024/cpp20240617.pdf.

services prices, with the market rent measure typically

leading the PCE measure by one year.

6

This relationship

is particularly evident in the periods following the

Great Recession and the COVID-19 pandemic. For

example, PCE housing services in ation reached a peak

of 8.3percent in April2023, exactly one year after the

12-month change for the CoreLogic index reached its

peak of 13.8percent.

Since mid-2022, each of these measures of market

rents has decelerated and returned to a growth rate

similar to or below its average pre-pandemic pace.

7

While the PCE price index for housing services also

began decelerating in mid-2023, its current rate of

increase remains well above the average rate seen

in the years before the pandemic. As noted earlier,

changes in the PCE price index for housing services

tend to lag changes in market rents because rental

6. Several studies use market rent measures to predict

housing services in ation. See, for instance, Marijn A. Bolhuis,

Judd N.L. Cramer, and Lawrence H. Summers (2022), “The

Coming Rise in Residential In ation,” Review of Finance,

vol.26 (September), pp. 1051–72; and Kevin J. Lansing,

Luiz E. Oliveira, and Adam Hale Shapiro (2022), “Will Rising

Rents Push Up Future In ation?” FRBSF Economic Letter

2022-03 (San Francisco: Federal Reserve Bank of

SanFrancisco, February), https://www.frbsf.org/wp-content/

uploads/sites/4/el2022-03.pdf.

7. In addition, the Bureau of Labor Statistics has recently

started publishing a quarterly rent index for new tenants (the

New Tenant Rent Index). While the New Tenant Rent Index

is subject to revision with each release, the year-over-year

growth of this index declined from its peak of 12.9percent in

the second quarter of 2022 to 0.4percent in the rst quarter

of 2024, the lowest reading since the second quarter of 2010.

See Bureau of Labor Statistics (n.d.), “New Tenant Rent Index,”

webpage, https://www.bls.gov/pir/new-tenant-rent.htm.

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Forecasters, conducted by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Philadelphia, continued to expect

PCE price ination to average 2percent over

the ve years beginning ve years fromnow.

Ination expectations over a shorter horizon—

which tend to follow observed ination more

closely and tend to be more volatile—have

moved down, on net, since the middle of

2022 to near the range seen during the decade

before the pandemic. In recent months, the

median value for ination expectations over

the next year as measured in theMichigan

survey has been generally lower than readings

from a year earlier. Similarly, expected

ination for the next year as measured in the

Survey of Consumer Expectations, conducted

by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, has

also declined, on average, from a year earlier.

Market-based measures of longer-term

ination compensation, which are based on

nancial instruments linked to ination such

as Treasury Ination-Protected Securities, are

also broadly in line with readings seen in the

years before the pandemic and consistent with

PCE ination returning to 2percent. These

measures have been little changed, on net,

since the beginning of the year (gure9).

The labor market remains strong

Payroll employment gains have been strong,

averaging 248,000 per month over the rst ve

months of the year. Job gains slowed from the

rst half to the second half of last year but

appear to have picked up, on net, so far this

year (gure10). Recent job gains have been

broad based, with over 60percent of industries

expanding their employment, on net, over the

three months ending in May. That said, gains

have been particularly strong in health care

and in state and local governments, where

employment remains below the levels implied

by pre-pandemic trends.

2

2. Administrative data from the Quarterly Census

of Employment and Wages (QCEW) suggest that job

growth last year was solid, but not as strong as reported

in the Current Employment Statistics (CES). The CES

5-year

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

4.0

Percent

202420232022202120202019201820172016

9. Ination compensation implied by Treasury

Ination-Protected Securities

Daily

5-to-10-year

N

OTE:The data are at a business-day frequency and are estimated

from smoothed nominal and ination-indexed Treasury yield curves.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Federal Reserve Board

sta calculations.

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

Thousands of jobs

2024202320222021

10. Nonfarm payroll employment

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data shown are a 3-month moving average of the change in

nonfarm payroll employment.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 13

The unemployment rate has edged up since the

middle of 2023 but was still at a historically

low level of 4.0percent in May. Through

May, the unemployment rate has remained

at or below 4percent for over two years

(gure11). Unemployment rates among most

age, educational attainment, sex, and ethnic

and racial groups remain near their respective

historical lows (gure12).

Labor demand has been gradually

cooling. . .

Demand for labor remained strong in the

rst half of 2024 but has continued to cool

gradually, on net, from its very elevated levels

of early 2022. Job openings, as measured in

the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

(JOLTS), have continued to fall from their all-

time high recorded in March2022 but are

payroll data will be revised in early 2025, when the

Bureau of Labor Statistics benchmarks these data to

employment counts from the QCEW as part of its annual

benchmarking process.

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Percent

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

12. Unemployment rate, by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE

: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identied as Hispanic or Latino

may

be of any race. Small sample sizes preclude reliable estimates for Native Americans and other groups for which monthly data are not reported b

y

the Bureau of Labor Statistics.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

Percent

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

11. Civilian unemployment rate

Monthly

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

still slightly above pre-pandemic levels.

3

An

alternative measure of job vacancies using job

postings data from the large online job board

Indeed also shows that while vacancies have

proceeded to move gradually lower through

the rst half of 2024, they have remained

above pre-pandemic levels.

4

Consistent with

the decline in job vacancies, the National

Federation of Independent Business (NFIB)

survey indicated that on net, in May, fewer

rms planned to add workers over the next

three months than was the case at the end of

2023; rms’ hiring plans reported in the NFIB

survey have been trending down since the

middle of 2021.

The cooling in labor demand has been

mostly due to reductions in rm hiring, as

indicators of layos, such as initial claims

for unemployment insurance and the rate of

layos and discharges in the JOLTS report,

have remained at historically low levels.

. . . and labor supply has increased

further . . .

Meanwhile, the supply of labor has continued

to increase on net. While labor force

participation has leveled o over the past year,

the U.S. population increased strongly because

of high levels of immigration.

The labor force participation rate (LFPR)—

which measures the share of people either

working or actively seeking work—increased

solidly from the beginning of 2021 through

the middle of 2023 but appears to have

3. Some analysts have noted that the vacancy-posting

behavior of rms may have changed since 2019 in ways

that lift the number of vacancies. For example, multi-

establishment rms may be posting vacancies for a

single job opening at several or all of its establishments

if the new job allows workers to work remotely from

any establishment. These multiple job postings may

result in overcounting of job vacancies in establishment-

level measures, such as those from JOLTS and Indeed.

Alternatively, after having experienced an exceptionally

strong labor market in 2022, rms may now be more

willing to post vacancies for positions that they are

unlikely to ll immediately.

4. Indeed job postings data are available on the

company’s Hiring Lab portal at https://data.indeed.com/

#/postings.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 15

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

Percent

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

13. Labor force participation rate

Monthly

NOTE:Data are monthly, and values before January 2024 are

estimated by Federal Reserve Board sta in order to eliminate

discontinuities in the published history.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

attened out at a relatively high level since

then. The LFPR was 62.5percent in May,

a touch below its average level over the past

12 months (gure13). Notably, the post-

pandemic recovery in the LFPR has diered

widely across demographic groups, with the

participation rate for women aged 25 to 54

reaching all-time highs in recent months and

the participation rate for individuals older

than 55 exhibiting no signs of recovery. (The

box “Employment and Earnings across

Demographic Groups” provides further

details.)

Labor supply has also been boosted in recent

years by relatively strong population growth

due to a notable expansion in immigration.

Though ocial estimates by the Census

Bureau show a robust increase in population

growth in 2022 and 2023, recent estimates

by the Congressional Budget Oce indicate

that actual population growth may have been

considerably higher. The most recent data

suggest that immigration is somewhat slower

than the strong rates seen late last year.

5

. . . resulting in a normalization of labor

market conditions

With cooling labor demand and rising labor

supply, the labor market became gradually less

tight over the rst half of this year, although

it nevertheless remains strong. The balance

between demand and supply in the labor

market appears similar to that during the

period immediately before the pandemic.

5. A recent report from the Congressional Budget

Oce (CBO) estimates that immigration in 2022 and

2023 was considerably higher than in the Census Bureau’s

estimates. See Congressional Budget Oce (2024), The

Demographic Outlook: 2024 to 2054 (Washington: CBO,

January), https://www.cbo.gov/publication/59697. Recent

studies have put more weight on the CBO estimates, in

part because the Census Bureau is using lagged estimates

of immigration from the American Community Survey,

while the CBO is using more recent, high-frequency data.

See Wendy Edelberg and Tara Watson (2024), “New

Immigration Estimates Help Make Sense of the Pace of

Employment,” Hamilton Project (Washington: Brookings

Institution, March), https://www.brookings.edu/

wp-content/uploads/2024/03/20240307_Immigration

Employment_Paper.pdf.

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Among prime-age people (aged 25 to 54), the

employment-to-population (EPOP) ratio for Black or

African American workers remained near its historical

peak in the rst half of 2024, and the gap in the EPOP

ratio between prime-age Black and white workers

fell to its lowest point in almost 50years. Similarly,

prime-age Hispanic or Latino workers’ EPOP ratio

has increased notably over the rst part of 2024 and

is now more than 1percentage point above its 2019

level ( gure A, top-left panel). That improvement has

further reduced the EPOP ratio gap between Hispanic

or Latino workers and white workers from already

At the aggregate level, solid labor demand and

improved labor supply, together with ongoing gains

in productivity and falling in ation, have resulted in

high rates of employment and rising real wages over

the past year. This solid labor market performance has

been broadly shared and has been especially bene cial

for historically disadvantaged groups of workers.

As a result, many of the long-standing disparities in

employment and wages by sex, race, ethnicity, and

education have narrowed, and some gaps reached

historical lows in 2023 and the rst half of 2024.

However, despite this narrowing, signi cant disparities

in absolute levels across groups remain.

Employment and Earnings across Demographic Groups

(continued)

Black or African American

Men, some college or more

Men, high school or lessAsian

Hispanic or Latino

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

202420232022202120202019

Race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

202420232022202120202019

Sex and educational attainment

Monthly

Women, some college or more

Women, high school or less

A. Prime-age employment-to-population ratios compared with the 2019 average ratio, by group

People without a disability

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

6

9

12

Percentage points

202420232022202120202019

Disability

Monthly

N

OTE

: Prime age is 25 to 54. All series are seasonally adjusted by the Federal Reserve Board sta.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

People with a disability

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 17

the average employment rate for this group.

4

For

persons without a disability, the EPOP ratio is little

changed from its 2019 level.

Although most groups have shown robust

employment gains over the past few years, the

EPOP ratio for people aged 55 or older remains

approximately 2percentage points below its 2019

level and has changed little since late 2021 ( gure B).

This shortfall is attributable to a persistent increase in

the rate of retirement among this group. Most of the

increase in retirement relative to 2019 is due to the

continued aging of the baby-boom generation, a trend

that was expected to have occurred even without the

pandemic.

5

However, retirements have also been

4. The increase in the number of persons with a disability

may be linked to cases of long COVID, which, while

debilitating, might not limit work as much as other types

of disabilities. As a result, an in ux of relatively higher-

employment individuals into the disabled category could have

raised employment rates for this group even if no individual’s

employment changed.

5. For example, as baby boomers have continued to age,

the median age of the population aged 55 or older increased

from 66 in 2019 to 67 in the rst half of 2024, and the median

age of that group is expected to continue increasing into

the future. This shift in the composition of the 55-or-older

population has naturally lowered the observed EPOP ratio for

this group nearly 0.5percentage point per year, as EPOP ratios

are lower at older ages.

historically low levels. Although the EPOP ratio for

prime-age Asian workers has moved somewhat lower

over the past year, it remains historically high and

above its 2019 level.

1

The EPOP ratio for prime-age women has continued

to increase steadily, reaching another record high in the

rst few months of 2024, whereas the EPOP ratio for

prime-age men has been mostly at over the past year,

near its level in the year before the pandemic ( gureA,

top-right panel). As a result, the EPOP ratio gap

between prime-age men and women fell to a record

low this year. The increase in the female EPOP ratio

relative to the pre-pandemic period is (almost) entirely

attributable to rising labor force participation, which

had also been increasing briskly before the pandemic,

consistent with a growing share of women with a

college degree.

2

Other factors, including strong labor

market conditions and greater availability of remote-

work options, may have also contributed to rising

prime-age female labor force participation.

3

Among prime-age persons with a disability, the

EPOP ratio has surged well above its 2019 level during

the past few years ( gure A, bottom panel). Some of

this increase is likely due to the unique labor market

circumstances of the past few years. With tight labor

market conditions, employers may have been relatively

more likely to hire persons with a disability than in

other times. Additionally, the rise of remote work may

have enabled persons with a disability to work without

the challenges of on-site work. However, some of the

increase could stem from a change in the composition

of this group, as the number of persons with a disability

rose following the pandemic, which may have raised

1. As monthly series have greater sampling variability

for smaller groups, we do not plot EPOP ratio estimates for

American Indians or Alaska Natives.

2. For a discussion of the contribution of educational

attainment to prime-age female labor force participation

before the pandemic, see Didem Tüzemen and Thao Tran

(2019), “The Uneven Recovery in Prime-Age Labor Force

Participation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City,Economic

Review, vol. 104 (Third Quarter), pp. 21–41, https://www.

kansascityfed.org/Economic%20Review/documents/652/2019-

The%20Uneven%20Recovery%20in%20Prime-Age%20

Labor%20Force%20Participation.pdf.

3. For a discussion on access to remote work and

participation rates, see Maria D. Tito (2024), “Does the

Ability to Work Remotely Alter Labor Force Attachment?

An Analysis of Female Labor Force Participation,” FEDS

Notes (Washington: Board of Governors of the Federal

Reserve System, January19), https://doi.org/10.17016/2380-

7172.3433.

(continued on next page)

Ages 16 to 24

Ages 55+

15

12

9

6

3

+

_

0

3

Percentage points

202420232022202120202019

B. Employment-to-population ratios relative to 2019

average, by age

Monthly

Ages 25 to 54

NOTE:Data before January 2023 are estimated by Federal R

eserve

Board sta in order to eliminate discontinuities in the published history.

S

OURCE:Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Curren

t

Population Survey; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

C. Median real wage growth, by group

4th quartile

White

1st quartile3rd quartile

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Wage quartiles

Monthly

2nd quartile

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Race

Monthly

Nonwhite

Men

High school or less

Bachelor’s degree or more

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Sex

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through March 2024. Series show 12-month moving averages of the median percent change in the hourly wage of individuals

observed 12 months apart, deated by the 12-month moving average of the 12-month percent change in the personal consumption expenditures price

index. In the top-left panel, workers are assigned to wage quartiles based on the average of their wage reports in both Current Population Survey

outgoing rotation group interviews; workers in the lowest 25 percent of the average wage distribution are assigned to the 1st quartile, and those in the

top 25 percent are assigned to the 4th quartile.

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Wage Growth Tracker; Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

Women

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Educational attainment

Monthly

Associate’s degree

by the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Wage Growth

Tracker and de ated by the personal consumption

expenditures price index—was consistently stronger for

workers in lower wage quartiles compared with the top

quartiles during the pandemic and early recovery, but

now all quartiles are experiencing similar growth.

7

Strong wage growth across the income distribution

is re ected in the experiences of different demographic

groups. Wage growth for nonwhite workers has been a

bit stronger than that for white workers for much of the

past year ( gure C, top-right panel). Wages for women

and men have grown essentially in tandem over the

past year ( gure C, bottom-left panel).

8

Real wage

growth for workers with a high school diploma or less

remains strong and has been rising a bit faster than for

workers with more education, on average, over the past

few years ( gure C, bottom-right panel).

7. To reduce noise due to sampling variation, which can

be pronounced when considering disaggregated groups’

wage changes, the series shown in gure C are the 12-month

moving averages of the groups’ median 12-month real wage

changes. Thus, by construction, these series lag the actual real

wage changes. Wage data extend through March2024 only to

avoid complications stemming from changes in the underlying

data source.

8. The measure of real wage growth shown in the gure

uses the same price index for all groups, but in ation

experiences can differ across demographic groups because

of differences in what they purchase or where they shop.

See Jacob Orchard (2021), “Cyclical Demand Shifts and

Cost of Living Inequality,” working paper, February (revised

September2022).

elevated above the level expected from aging alone,

mostly for individuals aged 65 or older.

6

While employment disparities across many

demographic groups are now within historically narrow

ranges, substantial gender, racial, and ethnic gaps

remain, underscoring long-standing structural factors.

Currently, prime-age women are employed at a rate

10 percentage points less than men, while prime-age

Black and Hispanic workers are employed at a rate

3to4percentage points less than white workers.

Similar to employment, a continued strong labor

market has supported strong nominal wage growth, and

as in ation has come down, that strong nominal wage

growth has translated into higher real wage growth.

Real wage growth has been comparatively robust for

historically disadvantaged groups. As shown in the top-

left panel of gure C, real wage growth—as measured

6. For an analysis on the increase in retirements following

the pandemic, see Joshua Montes, Christopher Smith, and

Juliana Dajon (2022), “ ‘The Great Retirement Boom’: The

Pandemic-Era Surge in Retirements and Implications for Future

Labor Force Participation,” Finance and Economics Discussion

Series 2022-081 (Washington: Board of Governors of the

Federal Reserve System, November), https://doi.org/10.17016/

FEDS.2022.081.

(continued)

Employment and Earnings (continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 19

C. Median real wage growth, by group

4th quartile

White

1st quartile3rd quartile

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Wage quartiles

Monthly

2nd quartile

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Race

Monthly

Nonwhite

Men

High school or less

Bachelor’s degree or more

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Sex

Monthly

N

OTE

: The data extend through March 2024. Series show 12-month moving averages of the median percent change in the hourly wage of individual

s

observed

12 months apart, deated by the 12-month moving average of the 12-month percent change in the personal consumption expenditures p

rice

index.

In the top-left panel, workers are assigned to wage quartiles based on the average of their wage reports in both Current Population Surve

y

outgoing

rotation group interviews; workers in the lowest 25 percent of the average wage distribution are assigned to the 1st quartile, and those in

the

top 25 percent are assigned to the 4th quartile.

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Wage Growth Tracker; Bureau of Labor Statistics; U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

Women

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

Percent

202420232022202120202019

Educational attainment

Monthly

Associate’s degree

20 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

A variety of labor market indicators support

this assessment. The ratio of job openings

to unemployment has fallen notably from its

peak of about 2.0 in spring 2022 to 1.2 in May,

the same as its average in 2019. Similarly, the

gap between the number of total available

jobs (measured by employed workers plus job

openings) and the number of available workers

(measured by the size of the labor force) has

also moved down markedly from its peak of

6.1million in spring 2022 to 1.4million in

May and is only a bit above its 2019 average of

1.2million (gure14). The unemployment rate

has continued to edge up this year and reached

4.0percent in May, modestly higher than in

2019. In addition, the percentage of workers

quitting their jobs each month, an indicator

of the availability of attractive job prospects,

has continued to move down this year and,

though still elevated, is now modestly below

its pre-pandemic level. Similarly, the share

of respondents to the Conference Board

Consumer Condence Survey reporting that

jobs are plentiful has continued to move down

and is somewhat lower than its level in 2019.

Furthermore, the NFIB survey indicates that

rms’ perceptions of labor market tightness

have come down from their recent peaks and

returned to their pre-pandemic range. Finally,

business contacts surveyed for the Federal

Reserve’s May2024 Beige Book reported signs

of a cooling labor market—including easing

in hiring plans, better labor availability, and

modest wage growth—and, similar to 2019,

cited some diculty nding workers in selected

industries or areas.

6

Wage growth remains elevated but

hasslowed

Consistent with the easing in labor market

tightness, nominal wage growth continued to

slow so far this year, though it remains above

its pre-pandemic pace and likely too high,

given productivity trends, to be consistent with

2percent ination over time (gure15). Total

hourly compensation, as measured by the

6. See the May2024 Beige Book, available on the

Board’s website at https://www.federalreserve.gov/

monetarypolicy/beigebook202405.htm.

Available workers

135

140

145

150

155

160

165

170

175

Millions

2024202220202018201620142012201020082006

14. Available jobs versus available workers

Monthly

N

OTE

: Available jobs are employment plus job openings as of the end

of the previous month. Available workers are the labor force. Data for

employment and labor force before January 2024 are estimated by

Federal Reserve Board sta in order to eliminate discontinuities in the

published history.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics; U.S. Census

Bureau; Federal Reserve Board sta calculations.

Available jobs

Average hourly earnings, private sector

Employment cost index, private sector

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Percent change from year earlier

202420232022202120202019201820172016

15. Measures of change in hourly compensation

N

OTE

: For the private-sector employment cost index, change is over

Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker

the 12 months ending in the last month of each quarter; for private-

sector average hourly earnings, the data are 12-month percent changes;

for the Atlanta Fed’s Wage Growth Tracker, the data are shown as a

3-month moving average of the 12-month percent change and

extend

through March 2024.

S: Bureau of Labor Statistics; Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta,

Wage Growth Tracker; all via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2024 21

employment cost index, increased 4.1percent

over the 12months ending in March, a

noticeable slowing from the peak increase

of 5.5percent in mid-2022. Other aggregate

measures of labor compensation, such as

average hourly earnings (a less comprehensive

measure of compensation) and the Federal

Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s Wage Growth

Tracker (which reports the median 12-month

wage growth of individuals responding to

the Current Population Survey), have also

continued to slow from their recent peaks in

2022 but remain well above their pre-pandemic

growth rates. Wage growth has not normalized

to the same extent as the measures of labor