This PDF is a selection from a published volume

from the National Bureau of Economic Research

Volume Title: NBER Macroeconomics Annual 2001,

Volume 16

Volume Author/Editor: Ben S. Bernanke and Kenneth

Rogoff, editors

Volume Publisher: MIT Press

Volume ISBN: 0-262-02520-5

Volume URL: http://www.nber.org/books/bern02-1

Conference Date: April 20-21, 2001

Publication Date: January 2002

Title: Do We Really Know that Oil Caused the Great

Stagflation? A Monetary Alternative

Author: Robert B. Barsky, Lutz Kilian

URL: http://www.nber.org/chapters/c11065

Robert

B.

Barsky

and

Lutz Kilian

UNIVERSITY

OF

MICHIGAN AND

NBER;

AND

UNIVERSITY OF

MICHIGAN,

EUROPEAN CENTRAL

BANK,

AND CEPR

Do

We

Really

Know

that

Oil

Caused

the

Great

Stagflation?

A

Monetary

Alternative

1.

Introduction

There

continues to be considerable

interest,

both

among policymakers

and

in

the

popular press,

in

the

origins

of

stagflation

and the

possibility

of its recurrence.

The traditional

explanation

of the

stagflation

of the

1970s found

in

intermediate textbooks is

an adverse shift

in

the

aggregate

supply

curve that lowers

output

and

raises

prices

on

impact.1

Indeed,

it

is

hard to see

in

such

a

static

framework how

a

shift

in

aggregate

demand

could have induced

anything

but a

move of

output

and

prices

in

the

same direction. This fact has lent credence to the

popular

view

that

exogenous

oil

supply

shocks

in

1973-1974

and 1978-1979 were

primarily

responsible

for

the

unique experience

of the 1970s

and

early

1980s.

For

example,

The

Economist

(November

27,

1999)

writes:

Could

the

bad

old

days

of inflation be about to return? Since OPEC

agreed

to

supply-cuts

in

March,

the

price

of crude oil has

jumped

to almost

$26

a

barrel,

up

from

less

than

$10

last December

and

its

highest

since the Gulf

war in

We

have benefited from comments

by

numerous

colleagues

at

Michigan

and

elsewhere.

We

especially

thank

Susanto

Basu,

Ben

Bernanke,

Olivier

Blanchard,

Alan

Blinder,

Mark

Gertler,

Jim

Hamilton,

Miles

Kimball,

Ken

Rogoff,

Andre

Plourde,

Matthew

Shapiro,

and

Mark

Watson. We

acknowledge

an

intellectual debt to

Larry

Summers,

who stimulated our

interest

in

the

endogeneity

of oil

prices.

Allison

Saulog

provided

able

research assistance.

Barsky

acknowledges

the

generous

financial

support

of the Sloan

Foundation. The

opin-

ions

expressed

in

this

paper

are those of the authors and do not

necessarily

reflect

views of

the

European

Central

Bank.

1.

For

example,

Abel

and

Bernanke

(1998,

p.

433)

write that-after a

sharp

increase

in

the

price

of

oil-"in the short run

the

economy

experiences stagflation,

with

both a

drop

in

output

and a

burst

in

inflation."

138

*

BARSKY & KILIAN

1991.

This

near-tripling

of oil

prices

evokes

scary

memories

of the 1973 oil

shock,

when

prices

quadrupled,

and

1979-80,

when

they

also almost

tripled.

Both

previous

shocks

resulted

in

double-digit

inflation

and

global

reces-

sion.

. .

.

Even

if

the

impact

will

be more

modest

this

time than

in

the

past,

dear

oil

will

still leave some mark.

Inflation will

be

higher

and

output

will

be

lower

than

they

would be

otherwise.

Academic

economists,

even

those who

may

not

fully agree

with

the

prevailing

view,

have done

little to

qualify

these

accounts

of

stagflation.

On

the

one

hand,

the recent

scholarly

literature has

focused on the

relationship

between

energy

prices

and

economic

activity

without

explic-

itly addressing stagflation

(see,

e.g., Hamilton,

1983, 1985, 1988, 1999;

Rotemberg

and

Woodford,

1996).

On the

other

hand,

some

authors

(e.g.,

Bohi, 1989;

Bernanke,

Gertler,

and

Watson,

1997)

have stressed not

the direct effects of oil

price

increases on

output

and

inflation,

but

possi-

ble indirect effects

arising

from the

Federal

Reserve's

response

to the

inflation

presumably

caused

by

oil

price

increases.

A

common

thread

in

the

popular press,

in

textbook

treatments,

and

in

the academic literature is that oil

price

shocks are

an

essential

part

of

the

explanation

of

stagflation.

In

contrast,

in

this

paper

we

make the case

that

the oil

price

increases were

not

nearly

as essential a

part

of

the

causal mechanism

generating

the

stagflation

of the 1970s as is often

thought.

We discuss reasons for

being skeptical

of the

importance

of

commodity

supply

shocks

in

general,

and the 1973-1974 and

1979-1980

oil

price

shocks

in

particular,

as the

primary explanation

of the

stagfla-

tion

of the 1970s.

First,

we show that there

were

dramatic and

across-

the-board

increases

in

the

prices

of industrial

commodities

in

the

early

1970s

that

preceded

the OPEC oil

price

increases. These

price

increases

do

not

appear

to be related to

commodity-specific supply

shocks,

but

are

consistent

with an

economic

boom fueled

by monetary expansion.

Sec-

ond,

there

is

reason

to doubt

that

the observed

high

and

persistent

inflation

in

the deflator

in

the

early

and late 1970s can be

explained

by

the 1973-1974

and

1979-1980 oil

price

shocks.

The

argument

that

oil

price

shocks caused

the Great

Stagflation depends

on the

claim

that

oil

price

shocks

are

inflationary. Using

a

simple

model,

we show

that

a

one-

time oil

price

increase

will

increase

gross output price

measures such

as

the

CPI,

but not

necessarily

the

price

of value

added,

as

proxied

by

the

GDP

deflator.

Indeed,

an

oil

price

increase

may

lower

the deflator.

Fur-

ther,

the

data show

that

only

two

of

the

five

major

oil

price

shocks

since

1970

have been followed

by significant changes

in

the inflation

rate of

the GDP

deflator,

though

in all

cases the CPI

inflation rate

changed

sharply

relative to the deflator.

Although

we

come

to the same conclu-

Do

We

Really

Know

that Oil Caused

the Great

Stagflation?

*

139

sion as Blinder

(1979)

that oil caused

a

spike

in

consumer-price

inflation

during

the two most

stagflationary

episodes,

we

show

that oil

prices

do

not

provide

a

plausible explanation

of

the

sustained

inflation that

oc-

curred

in

the GDP deflator as

well

as in the

CPI.

If

oil

price

shocks were not

the

source of the Great

Stagflation,

what

explains

the

striking

coincidence

of

the

major

oil

price

increases

in

the

1970s

and

the

worsening

of

stagflation?

In

this

paper

we

provide

evidence

that

in

the 1970s the rise

in

oil

prices-like

that

in

other

commodity

prices-was

in

significant

measure

a

response

to macroeconomic

forces,

ultimately

driven

by

monetary

conditions. This view coheres well

with

existing

microeconomic theories about the effect of real-interest-rate

varia-

tion

and

output

movements

on

resource

prices,

and

challenges

the con-

ventional wisdom

that

major

oil

price

changes

are

largely exogenous

with

respect

to

macroeconomic variables of OECD

countries.

It is

commonly

held

that

major

oil

price

movements are

ultimately

due to

political

events

in

the

Middle East. Our

analysis

suggests that-although political

factors

were

not

entirely

absent from

the

decision-making

process

of OPEC-the

two

major

OPEC

oil

price

increases

in

the 1970s would have been far less

likely

in

the

absence of conducive macroeconomic

conditions

resulting

in

excess

demand in

the

oil

market.

The

prevailing

view that

exogenous

oil

price

shocks were the

primary

culprits

of

the Great

Stagflation

of the

1970s

goes

hand

in

hand

with

the

perception

that

monetary

factors

do

not

provide

an

adequate explanation

of

stagflation.

In

this

paper

we

develop

more

fully

a

latent

dissent to

the

conventional

view that

monetary

considerations

cannot account for

the

historical

experience

of the 1970s.2

Bruno and

Sachs

(1985)

and,

to

a

lesser

extent,

Blinder

(1979,

p.

77)

discuss

monetary

expansion

as one

impor-

tant

source of

stagflation,

but their

emphasis

is

on the

inadequacy

of

money

as an

explanation

of

the bulk

of

stagflation

and

commodity price

movements.3 In

contrast,

we

show how

in

a

stylized

dynamic

model

of

the

macroeconomy stagflation

may

arise

endogenously

in

response

to

a

sustained

monetary

expansion

even in

the

absence of

supply

shocks.

The

data

generated

by

the

model

are

broadly

consistent,

both

qualitatively

2.

References that

we

identify

with the

traditional view

include

Samuelson

(1974),

Blinder

(1979),

and

Bruno and

Sachs

(1985).

Precursors of our

alternative

explanation

of

stagfla-

tion and its

association with oil

prices

include Friedman

(1975),

Cagan

(1979),

McKinnon

(1982),

Houthakker

(1987),

and

De

Long

(1997).

3.

For

example,

Bruno and

Sachs

(1985,

p.

6)

stress

the

inadequacy

of

purely

demand-side

models of

stagflation

and

propose

that

contractionary

movements in

aggregate

supply

(such

as

oil

price

shocks)

are

needed

to

explain

the

slide into

stagflation.

Blinder

(1979,

pp.

102,

209)

states that

the

inflation

of

1973-1974

was

simply

not

a

"monetary

phenome-

non." As

the causes of

the

inflationary surge

in

the

mid-1970s,

and

also

of the

recession

that

followed,

he

identifies

"special

factors"

such as

food

price

shocks

in

1972-1974,

the

oil

price

shock

in

1973,

and

the

dismantling

of

price

controls

in

1974.

140

*

BARSKY &

KILIAN

and

quantitatively,

with

the

dynamic properties

of

the actual

output

and

inflation data

for

1971-1975.

Our model

captures

the notion

that

eco-

nomic

agents

in

the 1970s

responded only

gradually

to

shifts

in

the mone-

tary policy

regime.

We

link

these shifts to the breakdown of the Bretton

Woods

system

and to

changes

in

policy

objectives.

Several indicators

of

monetary

policy

stance show

that

monetary policy

in

the

United

States,

in

particular,

exhibited

a

go-and-stop pattern

in

the 1970s.

Moreover,

episodes

of

stagflation

were associated

with

swings

in

worldwide

liquid-

ity

that

dwarf

monetary

fluctuations elsewhere

in

our

sample.

The

remainder of

the

paper

is

organized

as follows.

We

begin

with an

outline

of

the

basic facts of the

stagflation

of

the

1970s

in

Section

2.

Section

3

presents

a

monetary

explanation

of

stagflation.

In

Section

4

we

examine

the

empirical support

for this

monetary explanation,

and

in

Section

5 the

reasons for

the shifts

in

monetary

policy

stance

that

in

this view

ulti-

mately triggered

the Great

Stagflation.

In

Section

6 we discuss theoretical

and

empirical

arguments against

the

oil-supply-shock

explanation

of

stag-

flation.

Finally,

in

Sections

7 and

8 we discuss the theoretical reasons

for

a

close

relationship

between

oil

prices

and macroeconomic

variables

and

provide

evidence

that oil

prices

were

in

substantial

part

responding

to

macroeconomic

forces,

rather

than

merely

political

events

in

the

Middle

East. Additional

evidence

from the most recent

oil

price

increase

is dis-

cussed

in

Section

9. Section

10 contains the

concluding

remarks.

2. Basic

Facts

This

section

describes some

of

the salient features

of

stagflation

and of

the

evolution

of oil

prices

in the

postwar period.

The 1970s

and

early

1980s

were

an

unusual

period

by

historical

standards.

Table

1

describes

the

pattern

of

inflation

and of GDP

growth

for each

of the

NBER

business-cycle

contractions

and

expansions.

For each

phase,

we

present

data on nominal

GDP

growth

and its breakdown

into real

and

price

components.

Two

critical observations

arise

immediately

from

Table

1.

First,

with one

exception,

the

phase

average

of the

rate of

inflation

rose

steadily

from

1960.2

to

1981.2,

and

declined

over

time

thereafter.

The

exception

is that

inflation

was 2.5

percentage

points

lower

(9.56%

com-

pared

with

6.98%)

during

the 1975.1-1980.1

expansion

than

in

the

pre-

ceding

contraction

period

from 1973.4

to

1975.1.

The

second,

and most

important,

observation

is

the

appearance

of

stagflation

in

the

data.

Stagflation

appears

in

Table

1

as

an

increase

in

inflation

as

the

economy

moves

from an

expansion

to

a

contraction

phase.

There

were

three

episodes

in

which

inflation,

as

measured

by

the

growth

in

the GDP

deflator,

was near

9%

per

annum.

In

two of

these

Do We

Really

Know that Oil Caused

the

Great

Stagflation?

*

141

Table

1 REAL

GROWTH, INFLATION,

AND NOMINAL

GROWTH

IN

THE

UNITED STATES

NBER business-

State

of

the

Percent

change per

annum

NBER business-

State

of

the

cycle

dates

economy

Real

growth Inflation

Nominal

growth

1960.2-1961.1

Contraction

-1.03

+1.22

+0.19

1961.1-1969.4

Expansion

+4.64

+2.59 +7.23

1969.4-1970.4

Contraction

-0.49

+4.93

+4.44

1970.4-1973.4

Expansion

+4.34

+5.22 +9.56

1973.4-1975.1 Contraction

-1.76 +9.56

+7.80

1975.1-1980.1

Expansion

+3.80

+6.98 +10.78

1980.1-1980.2 Contraction

-3.46 +8.88 +5.42

1980.2-1981.2

Expansion

+0.62

+9.11 +9.73

1981.2-1982.4 Contraction

-1.34

+6.07 +4.73

1982.4-1990.2

Expansion

+4.07 +3.29

+7.36

1990.2-1991.1 Contraction

-1.27

+4.12

+2.85

1991.1-2001.1

Expansion

+3.46

+2.10 +5.56

Source: Based on

quarterly chain-weighted

GDP

and

GDP

deflator data from

DRI

for 1960.1-2001.1. The

business-cycle

dates

are based on the NBER

dating.

The last

expansion

is

incomplete.

three

episodes

real

output

contracted

sharply

(i.e.,

in

1973.4-1975.1

and

1980.1-1980.2),

and

in

the

third it

grew

very

slowly

(i.e.,

in

1980.2-

1981.2).

Indeed,

in

all but

one contraction

(i.e.,

with

the

exception

of the

second Volcker recession

in

1981.2-1982.4),

average

inflation

during

the

contraction was

higher

than

during

the

previous

expansion.

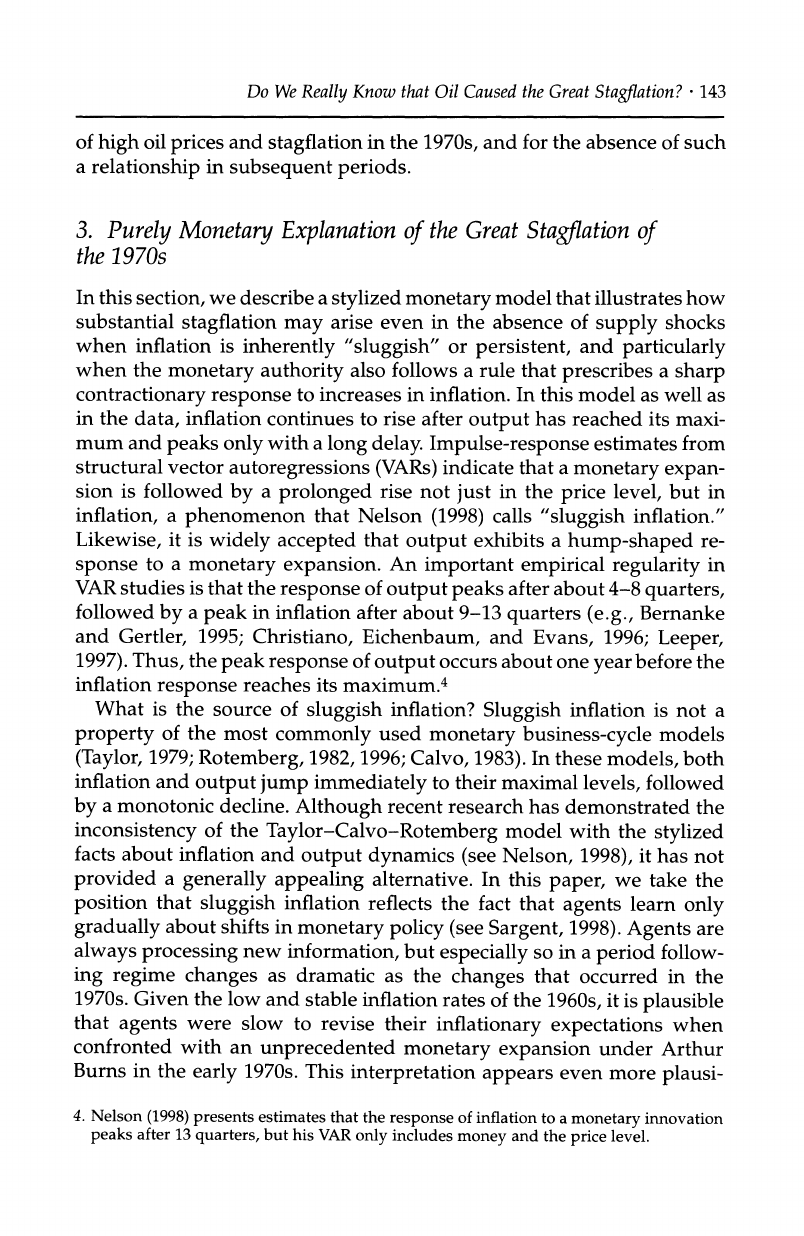

Figure

1

shows the

percentage change

in

the nominal

price

of

oil since

March

1971,

when

the

U.S. became

dependent

on oil

imports

from the

Middle East

(see

Section

8).

Episodes

of so-called oil shocks are

indicated

by

vertical bars

and

include the 1973-1974 OPEC oil

price

increase

after

the October

war

of

1973,

the 1979-1980

price

increases

following

the

Iranian

revolution

in

late 1978 and the

outbreak of the

Iran-Iraq

war

in

late

1980,

the

collapse

of OPEC

and

of the oil

price

in

early

1986,

the

oil

price spike

following

the invasion of Kuwait

in

1990,

and

the most

recent

period

of

OPEC

price management

since March 1999.

The

coincidence of

two

large

increases

in

the

price

of

imported

oil

in

the

1970s

and

two

periods

of

strong stagflation

has

spurred

interest

in

a

causal link

from

"oil

shocks" to

stagflation,

although

casual

inspection

of

Figure

1

and

Table

1

suggests

that

this

link

is

far

less

apparent

for other

episodes.

The

decade of

the 1970s also

coincided

with

fundamental

changes

in

monetary policy

and in

attitudes

toward

inflation,

as the Bretton

Woods

system

collapsed.

Monetary policy

became much

more

expansionary

on

average

and

more

unstable

in

the

1970s

than in

the

1960s. One

reason

that

these

developments

are

often

considered less

important

in

discus-

142

*

BARSKY

&

KILIAN

Figure

1

PERCENTAGE CHANGE IN NOMINAL

PRICE

OF OIL

50-

40-

30-

20-

10-

0

-10-

-20-

-30

-

-40-

-50

Source:

The

underlying

oil

price

series is

refiner's

acquisition

cost of

imported

crude

oil

(DRI

code:

EEPRPI)

for

January

1974 to

July

2000. We use the U.S.

producer

price

index for oil

(DRI

code:

PW561)

and

the

composite

index for refiner's

acquisition

cost of

imported

and domestic

crude oil

(DRI

code:

EEPRPC)

to

extend

the data

back

to March

1971.

sions

of

stagflation

is the

perception

that

monetary

factors are

unlikely

to

generate stagflation

of sufficient

magnitude

(see

Blinder,

1979).

As

we

will

show

in

Section

3,

this

perception

is incorrect. Another reason for

the

popularity

of

the

oil-price-shock

explanation

of

stagflation

is

the

fact that

both

the

phenomenon

of

stagflation

and that

of

major

upheavals

in

the oil

market

occurred for the

first

time

in

the

1970s,

although

Table 1

suggests

that

stagflation predates

the

first

oil

price

shock

of late

1973.

Although

oil

price

shocks continue

to

occur,

there

have been

no

major episodes

of

stagflation

since the 1970s.

In

this

paper

we

question

the

extent

to

which

we

really

know

that oil

price

shocks

played

a

central role

in

generating

stagflation.

We

will

show

that a

monetary

approach

can

explain

not

only

the

evolution of

the

Great

Stagflation,

but

also

that of

the

price

of

oil

during

that

period.

We

will

present

a

coherent

explanation

for the

almost simultaneous occurrence

I

Do We

Really

Know

that Oil

Caused

the Great

Stagflation?

*

143

of

high

oil

prices

and

stagflation

in

the

1970s,

and

for the absence

of

such

a

relationship

in

subsequent

periods.

3.

Purely Monetary Explanation

of

the

Great

Stagflation of

the 1970s

In

this

section,

we

describe

a

stylized

monetary

model

that

illustrates

how

substantial

stagflation may

arise even

in

the

absence of

supply

shocks

when

inflation is

inherently

"sluggish"

or

persistent,

and

particularly

when

the

monetary

authority

also

follows

a

rule

that

prescribes

a

sharp

contractionary

response

to increases in inflation.

In

this model

as well

as

in

the

data,

inflation

continues to rise after

output

has

reached

its

maxi-

mum and

peaks

only

with a

long

delay. Impulse-response

estimates

from

structural

vector

autoregressions

(VARs)

indicate

that a

monetary expan-

sion is

followed

by

a

prolonged

rise not

just

in

the

price

level,

but in

inflation,

a

phenomenon

that

Nelson

(1998)

calls

"sluggish

inflation."

Likewise,

it is

widely

accepted

that

output

exhibits

a

hump-shaped

re-

sponse

to

a

monetary

expansion.

An

important empirical

regularity

in

VAR

studies is that the

response

of

output

peaks

after about

4-8

quarters,

followed

by

a

peak

in

inflation

after about 9-13

quarters

(e.g.,

Bernanke

and

Gertler, 1995;

Christiano,

Eichenbaum,

and

Evans, 1996;

Leeper,

1997).

Thus,

the

peak

response

of

output

occurs about

one

year

before the

inflation

response

reaches its maximum.4

What

is the

source

of

sluggish

inflation?

Sluggish

inflation is

not

a

property

of

the most

commonly

used

monetary

business-cycle

models

(Taylor,

1979;

Rotemberg,

1982,1996;

Calvo,

1983).

In

these

models,

both

inflation

and

output jump

immediately

to their maximal

levels,

followed

by

a

monotonic decline.

Although

recent

research has

demonstrated the

inconsistency

of the

Taylor-Calvo-Rotemberg

model with

the

stylized

facts about

inflation

and

output dynamics

(see

Nelson,

1998),

it

has

not

provided

a

generally

appealing

alternative.

In

this

paper,

we take the

position

that

sluggish

inflation

reflects

the fact that

agents

learn

only

gradually

about shifts in

monetary

policy

(see

Sargent,

1998).

Agents

are

always

processing

new

information,

but

especially

so in a

period

follow-

ing regime

changes

as

dramatic as

the

changes

that

occurred

in

the

1970s.

Given the

low and

stable

inflation

rates of the

1960s,

it

is

plausible

that

agents

were slow

to

revise their

inflationary expectations

when

confronted

with an

unprecedented

monetary

expansion

under Arthur

Burns in

the

early

1970s.

This

interpretation

appears

even

more

plausi-

4.

Nelson

(1998)

presents

estimates that

the

response

of inflation

to a

monetary

innovation

peaks

after 13

quarters,

but

his VAR

only

includes

money

and

the

price

level.

144

*

BARSKY & KILIAN

ble

considering

the financial

turmoil and

uncertainty

associated

with

the

gradual

disappearance

of

the Bretton Woods

regime. Similarly, expecta-

tions

of

inflation

were slow to

adjust

in the

early

1980s,

when Paul

Volcker launched

a new

monetary policy regime resulting

in

much lower

inflation.

We

propose

a

stylized

model that

formalizes

the notion

that in times of

major

shifts

in

monetary policy

inflation is

likely

to

be

particularly slug-

gish.

Consider

a

population

consisting

of two

types

of

firms.

A

fraction

(,t

of

"sleepy"

firms is not convinced

that

a

shift

in

monetary

policy

has

taken

place

and

sets

its

output price

(pt)

at

last

period's

level

adjusted

for

last

period's

inflation

rate. The

remaining

fraction

1

-

w,

of "awake"

firms

is

aware of the

regime

change

and sets its

output

price

at

P?t

=

Pt

+

l3(Yt

-

yf),

where 8

is a

constant,

Yt

the

log

of real

GDP,

and

yf

the

log

of

potential

real GDP.

As time

goes

by,

the fraction

of

agents

that

is

un-

aware of

the

regime

change

evolves

according

to

wt

=

e-At.

These consider-

ations

imply

an

aggregate

price-setting equation

of

the form

Pt =

wtP

+ (1

- t)pt

=

e-'t

(2pt_1

-

Pt2)

+ (1

-

e-t)

[p,

+

(t

- yf)].

(la)

This

price

equation

is the source of

the inflation

persistence

in our

model.

Equation

(la)

is

very

much

in

the

spirit

of

Irving

Fisher's

(1906)

reference

to

an

earlier

monetary expansion

that

"caught

merchants

nap-

ping."

Its

motivation is closer

to that

of the Lucas

supply

schedule

(see

Lucas,

1972,

1973)

than

to that of

sticky-price

models.

Agents

are

always

free

to

adjust prices

without

paying

"menu costs."

Moreover,

by

the

choice

of

appropriate

time-varying

weights

wt,

our

inflation

equation

may

allow

for the

fact that

agents

learn more

quickly

about

some

shifts

in

policy

than about others.

For

expository

purposes,

however,

we

postu-

late

that these

weights

evolve

exogenously.

The second

building

block of

the model

is the

equation

Ayt

=

Amt

-

Apt,

(lb)

where

Apt

is

the

inflation

rate

(which

we

will

associate

with the rate of

change

of the GDP

deflator)

and

Amt

is the

rate of nominal

money

growth.

This

relationship

is

a

very

simple

money

demand

equation.

We

complete

the

model

by

adding

a

policy

reaction function.

We

posit

that

the Fed

cannot

observe

the current

level

of the

GDP

deflator.

We

postulate

a

reaction

function

under which

the

Fed

targets

the rate of

inflation.

Let

"-ew

be

the

steady-state

rate of inflation

consistent

with

the

initial

increase

in

money growth.

That

rate

may

be

interpreted

as

the

level of

inflation

that the Fed

is

willing

to tolerate

under

the new

expan-

Do We

Really

Know that

Oil Caused

the

Great

Stagflation?

?

145

sionary regime.

The Fed

responds

to

periods

of inflation

in excess of

,new

by decelerating

monetary growth by

some small fraction

y

of last

pe-

riod's excess

inflation rate:

A2mt

=

-y

Ap,_

I(Apt_1

>

fnw)

+

At,,

(Ic)

where

I(-)

denotes

the indicator

function,

and

Et

represents

the

increase

in

the

money

growth

rate

associated

with the Fed's more

expansionary

policy

after

the

collapse

of

the

Bretton Woods

system.

Note

that,

holding

constant other demand shifters

and

given

the

sluggishness

of

inflation,

this

money growth

rule

may

be translated into a more

conventional

interest-rate rule

by

inverting

an

IS curve

and

observing

that

high

real

balances

imply

low real interest rates.

In

addition,

by

way

of

compari-

son,

we

will

explore

a

much

simpler

model

in which

money supply

growth

follows

a

sequence

of

exogenous policy

shocks

Et

and

in

which

there

is no

policy

feedback:

A2mt

=

AEt. (lc')

The

model is

parametrized

as follows.

We

postulate

that

in

steady

state

output

grows

at

3%

per

annum.

Moreover,

prices

grow

at a

steady

rate of 3%

per

annum

prior

to the

monetary expansion.

We

follow

Kim-

ball

(1995)

in

setting

3

=

0.06. The

single

most

important parameter

in

the

model is

A,

which

determines the fraction of

agents

"awake." We

choose

A

to

give

our

model the

best

possible

chance to

match the

timing

of

business-cycle

peaks

and

troughs

in

the U.S. inflation and

output-gap

data

for 1971-1975.

The

resulting

value of

A

=

0.08

implies

that after

two

years

slightly

less

than

half of

economic

agents

will

have

adopted

the

new

pricing

rule.

This rate of

transition

may

appear

slow,

but-as we

will

discuss

below-is consistent with

evidence from other

sources as

well.5

Finally,

for

the model with

policy

feedback,

we

choose

y

=

0.05 for

illustrative

purposes.

This value

means

that, if,

for

example,

the inflation

rate last

quarter

is

2%,

the Fed will

decelerate

monetary growth

by

0.1

percentage point

(one-tenth

of

the initial

monetary expansion).

Our

choice of

y

ensures

that

the inflation

rate

returns to the initial

steady-

5.

In

our

model

it

takes about

two

years

for half

of the

agents

to

adopt

the

new

pricing

rule.

This

rate of

adaptation

may appear

very

slow,

but it

is not unlike

those found in

many

other

economic

contexts. For

example,

data

from

the literature on

the

entry

of lower-

priced

generics

into

the

market for

branded

drugs

show that

after two

years

only

about

half

of

the

consumers have

switched

to the

lower-priced generic

drug

(see

Griliches and

Cockburn, 1994;

Berndt,

Cockburn,

and

Griliches,

1996).

If

it

takes so

long

for

agents

to

adapt

in

such

a

simple problem,

it

does

not

appear implausible

that it

would

take

at

least

as

long

in

our

context.

146

*

BARSKY &

KILIAN

state rate

in

the

long

run.

This choice is consistent with the

interpreta-

tion

that the Fed-rather than

discovering

a solution to

the

dynamic

inconsistency

problem-found

its

way

back to low inflation

using

a

mechanical

rule

(see

Sargent,

1998).

Given this choice

of

parameters,

consider

a

one-time shock

to

E,

in

period

5,

representing

a

4-percentage-point-per-annum

increase

in

money growth, beginning

in

steady

state.

Figure

2a

shows

that

a

mone-

tary expansion

produces

the

essential features discussed above.

The

model

economy displays stagflation, sluggish

inflation,

and a

hump-

shaped response

of

output

to a

monetary expansion.

Most

importantly,

the

output gap

rises

with

the inflation rate

initially,

with

output peak-

ing

about two

years

after the

shock,

whereas inflation

peaks only

after

three

years

(close

to

the 13

quarters reported by

Nelson,

1998).

Between

these

two

peaks

output

and inflation move

in

opposite

directions,

re-

sulting

in

stagflation.

We now address

the extent to which

this

stylized monetary

model

can

explain

the

business-cycle

peaks

and

troughs

over the 1971-1975

period.

Consider

the

following

thought experiment:

Since

we know

that

a

strong

monetary expansion

took

place starting

in

the

early

1970s,

we-somewhat

arbitrarily-propose

to date the

monetary expansion

in

the

model so

that

period

5

in

Figure

2a

corresponds

to

1971.1. This

thought experiment

allows

us

tentatively

to

compare

the behavior

of

output

and inflation

in

the model

in

response

to a

monetary

expansion

with the actual

U.S.

data.

Given

this

interpretation,

the

monetary

model

predicts

a

peak

in

GDP

in

1972.4-1973.1,

followed

by

a

peak

in

deflator

inflation

in 1974.2

(shortly

after the

OPEC oil

price

increase)

and

a

trough

in

GDP

in 1975.2. Note

that,

although

the

NBER

dates

the

end

of the

expansion

in late

1973,

Hodrick

and Prescott

(HP)

detrended

GDP

peaks

in

1973.1,

at

the same

time as

the

gap peaks

in

our model.

Thus,

the

timing

of the

cycle

that would

have

been

induced

by

the

monetary

expansion

in

1971.1

(after

allowing

for the

Fed's reaction

to

the

changes

in inflation set

in

motion

by

this

initial

expansion)

is re-

markably

close

to the

timing

of

the actual business

cycle.

Note that

this

coincidence

of

the

timing

of

the

business-cycle

peaks

and

troughs

does

not

occur

by

construction,

but arises

endogenously

given

our

choice

of

parameters.

Continuing

with

the

same

analogy,

we now

focus

on the

magnitude

of

the

output

and

price

movements

induced

by

the

monetary

expansion.

Of

particular

interest

is

the

ability

of the

model

to

match

the

phase

averages

for 1971.1-1973.3

and for

1973.4-1975.1.

We find that

the

aver-

age per

annum

inflation

rates

for

1971.1-1973.3

and

1973.4-1975.1

in

the

model

are

fairly

close

to

the U.S.

data.

The model

predicts

average

inflation rates

of

5.1%

and

10.4%

per

annum,

respectively,

compared

Do We

Really

Know

that

Oil

Caused

the Great

Stagflation?

*

147

Figure

2 IMPLICATIONS OF A PURELY MONETARY

MODEL OF

STAGFLATION:

(a)

WITH POLICY

FEEDBACK;

(b)

WITHOUT

POLICY

FEEDBACK

0.08

0.06-

,,"

',\

0.04-

0.02-

0.00--

\

-0.02-

-0.04

-

-0.06

5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40

(a)

0.08

0.06-

,,

x\

'"\

0.04-

0.02-

"

/

,

/zi

'

0.00

-----

-0.02-

-0.04

5 10 15

20 25 30

35

40

(b)

Notes: Solid

curves:

quarterly

inflation

rate.

Dashed curves:

output gap.

Models described in

text.

Responses

to

a

permanent

1-percentage-point

increase

in

money

growth

in

period

5.

148

*

BARSKY & KILIAN

with

4.9%

and

9.6%

in

the

data.

Thus,

both

the model and

the

data

show

a

substantial

increase

in

inflation

during

the

recession.

Similarly,

for

GDP

growth

the model fit

is not

far

off. The

model

predicts

4.8%

growth

per

annum for

1971.1-1973.3

compared

with 5.2% in

the

data,

and

-3.0% for

1973.4-1975.1

compared

with -1.8% in the data.

We

conclude

that the

quantitative

implications

of

this model are not

far

off

from

the U.S.

data,

especially

considering

that we

completely

ab-

stracted

from other

macroeconomic determinants. Also note

that the

Fed

inflation

target

in

our model

economy

becomes

binding

in

early

1973,

consistent

with the

empirical

evidence of

a

monetary

tightening

in

early

1973

in

response

to actual and

incipient

inflation

(see

Section

4).

This

example

illustrates

that

go-stop monetary

policy

alone could

have

generated

a

large

recession

in

1974-1975,

even

in

the

absence

of

supply

shocks.

A

question

of

particular

interest is how essential

the

endogenous pol-

icy

response

of the

Fed

is

for the

generation

of

stagflation.

Some authors

have

argued

that the

1974

recession

may

be

understood

as

a

conse-

quence

of

the Fed's

policy response

to

inflationary expectations

(e.g.,

Bohi,

1989; Barnanke,

Gertler,

and

Watson,

1997).

Figure

2b shows that

policy

reaction

is an

important,

but

by

no

means

essential,

element of

the

genesis

of

stagflation.

In

fact,

a

qualitatively

similar

stagflationary

episode

would

have

occurred

under the

alternative

policy

rule

(lc')

with-

out

any

policy

feedback. The

main

effect of

adding policy

feedback

(y

>

0)

is

to increase

the

amplitude

of

output

fluctuations

and

to

dampen

variations

in

inflation.

In

the model

without

policy

feedback,

holding

fixed

the

remaining

parameters,

the

timing

of the

cycle

induced

by

the

monetary

regime

change

is

roughly

similar

to

that

in

Figure

2a.

Figure

2b shows

a

peak

in

GDP

in

1972.4-1973.1,

followed

by

a

peak

in inflation

in

1974.3

and

a

trough

in

GDP

in

1975.2.

The model

without

policy

feedback

predicts

average

annual

inflation rates

of 5.1%

and 12.0% for

1971.1-1973.3

and

1973.4-1975.1,

respectively,

compared

with

4.9% and 9.6%

in the

U.S.

data.

Average

output growth

per

annum over

these same

subperiods

is

4.9%

and

-2.0%,

respectively,

in the

model,

compared

with 5.2%

and

-1.8%

in the data.

The

policy

shift

associated

with

the

monetary

tightening

under Paul

Volcker

in

late

1980

provides

a

second

example

of the

basic mechanism

underlying

our

stylized

model.

Using

the

same

parametrization

as

for

Figure

2b,

our model

predicts

a

sharp

recession

in

late

1982,

followed

by

an

output

boom

in

1985

and

an

output

trough

in

early

1987. This

pattern

closely

mirrors

the movements

of HP-filtered

actual

output.

At the

same

time,

inflation

in

the model falls

sharply,

reaching

its

trough

in

1984,

Do We

Really

Know

that

Oil Caused the Great

Stagflation?

*

149

followed

by

a

peak

in

1986. Actual inflation in the GDP

deflator

followed

a

qualitatively

similar,

but

delayed pattern.

It

reached

its

trough

in

1986,

followed

by

a

peak

in

mid-1988.

Thus,

the

response

of

actual inflation

in

this

episode

is even more

sluggish

than

that

in

the model.

4

Supportfor

the

Monetary

Explanation

of

Stagflation

In

this

section,

we

will

present

four

additional

pieces

of evidence

in

support

of

the

monetary

explanation

of

stagflation.

First,

we

will

exam-

ine several indicators

of

monetary

policy

stance to show

that

monetary

policy

in

the

United

States,

in

particular,

exhibited

a

go-and-stop pattern

in the

1970s.

Second,

we

will

show

that

episodes

of

"stagflation"

were

associated

with

swings

in

world-wide

liquidity

which dwarf

monetary

fluctuations elsewhere

in

our

sample.

Third,

we

will

show

that

there

were

dramatic and

across-the-board increases

in

the

prices

of

industrial

commodities

in

the

early

1970s

that

preceded

the OPEC

oil

price

in-

creases.

These

price

increases

do

not

appear

to be

related to

commodity-

specific supply

shocks,

but are

consistent

with

an

economic

boom

fueled

by monetary

expansion. Finally,

we

will

document

that

in

early

1973

a

broad

range

of

business-cycle

indicators started to

predict

a

recession,

nine

months before the

first OPEC

oil

crisis,

but

immediately

after

the

Fed

began

to

tighten

monetary policy.

4.1

EVIDENCE OF

GO-AND-STOP MONETARY

POLICY

IN THE

UNITED STATES

Our

evidence is based on two

measures of the total

stance of

monetary

policy

for this

period-one

based

on the behavior

of the Federal

Funds

rate,

the

other

based on

narrative evidence

(see

Bernanke

and

Mihov,

1998;

Boschen and

Mills,

1995).

The

Bernanke-Mihov index of

the over-

all

monetary

policy

stance shows

a

strongly

expansionary

stance

from

mid-1970

to the

end

of 1972

(see

Figure

3).

Interestingly,

the

Boschen-

Mills

index,

which is

based on

narrative

evidence,

is

mostly

neutral

during

this

period

with

the

exception

of

1970-1971.

The reason

is

that

the

Boschen-Mills

index is based

on

policy

pronouncements

as

opposed

to

policy

actions.

Quite

simply,

the Fed's

pronouncements

in

this

period

were

uninformative

at

best and

probably

misleading.

Both

the

Boschen-Mills index and

the

Bernanke-Mihov

index

show

a

sharp

tightening

of

monetary

policy

in

early

1973.

The

Boschen-Mills

indicator,

on

a

scale from

+2

(very

expansionary)

to

-2

(very

tight),

moves

from neutral at

the

end of 1972

to

-1

for

the first

three

months of

1973. It

then

spends

the

next 6

months at

-2,

followed

by

two

months at

-1,

ending

the

year

in

neutral.

Further,

the

Bernanke-Mihov

index

shows a

sharp

and

prolonged

contraction

in

monetary

policy

by

early

1973

150

*

BARSKY

& KILIAN

Figure

3

INDICATOR OF OVERALL

MONETARY POLICY

STANCE,

JANUARY

1966

TO

DECEMBER 1988

0.

1968

1970 1972

1974 1976 1978

Source:

Courtesy

of B. Bernanke and

I.

Mihov.

(see

Figure

3).6

As noted

by

Boschen and Mills

(1995),

this contraction

was

an

explicit

response

to

rising

inflation. It

occurred

long

before the distur-

bances

in

the oil market

in

late 1973 and

provides

an

alternative

explana-

tion

of

the recession

in

early

1974.7 The

contractionary

response

of the

Fed

in 1973 to

the

inflationary pressures

set

in

motion

by

earlier Fed

policy

is

a

key

element

of

our

monetary explanation

of

stagflation.8

Note

that the

observed increase

in

inflation

in

1973 is understated

as a result of

price

controls,

and

the observed

increase

in

1974 is overstated

due

to

the

lifting

of the

price

controls

(see

Blinder,

1979).

6. The

downturn in the

Bernanke-Mihov index in

1973 reflects a

sharp

rise

in

the Federal

Funds rate.

Interestingly,

as

Figure

5d

shows,

although

the real interest

rate

rose,

it

remained

negative throughout

1974.

Thus,

the

contractionary

effect of the

monetary

tightening

must have worked

partly through

other channels such as

the

effect of

high

nominal

interest rates on

housing

starts in

the

presence

of

disintermediation

due

to

interest-rate

ceilings.

7.

This

interpretation

is

consistent

with

Bernanke,

Gertler,

and

Watson's

(1997)

conclusion

that

the Fed in 1973 was

responding

to the

inflationary

signal

in

non-oil

commodity

prices,

not to the oil

price

increase as is

commonly

believed.

8.

There

is

no Romer date for

1973,

despite

the clear evidence of a

shift

in

policy

toward a

contractionary

stance.

Do We

Really

Know

that

Oil Caused the Great

Stagflation?

?

151

As the

U.S.

economy

slid

into recession

in

1974,

the Fed

again

re-

versed course to

ward off

an

even

deeper

recession.

Indicators show

a

renewed

monetary expansion

that lasted

into

the late 1970s. The

Ber-

nanke-Mihov index indicates

that

monetary policy

was

strongly

expan-

sionary

from late 1974

into 1977

(see

Figure

3).

This

expansion

was

not

initially

reflected

in

high

inflation,

in line with our earlier discussion

of

sluggish

inflation.

Boschen and Mills record

a

similar,

if

somewhat

briefer,

expansion.

Around

1978,

the

monetary

stance turned

slightly

contractionary, becoming strongly

contractionary

in late 1979 and

early

1980 under Paul

Volcker,

as inflation continues

to worsen. Once

again,

the

monetary policy

stance

provides

an alternative

explanation

for the

genesis

of

stagflation.

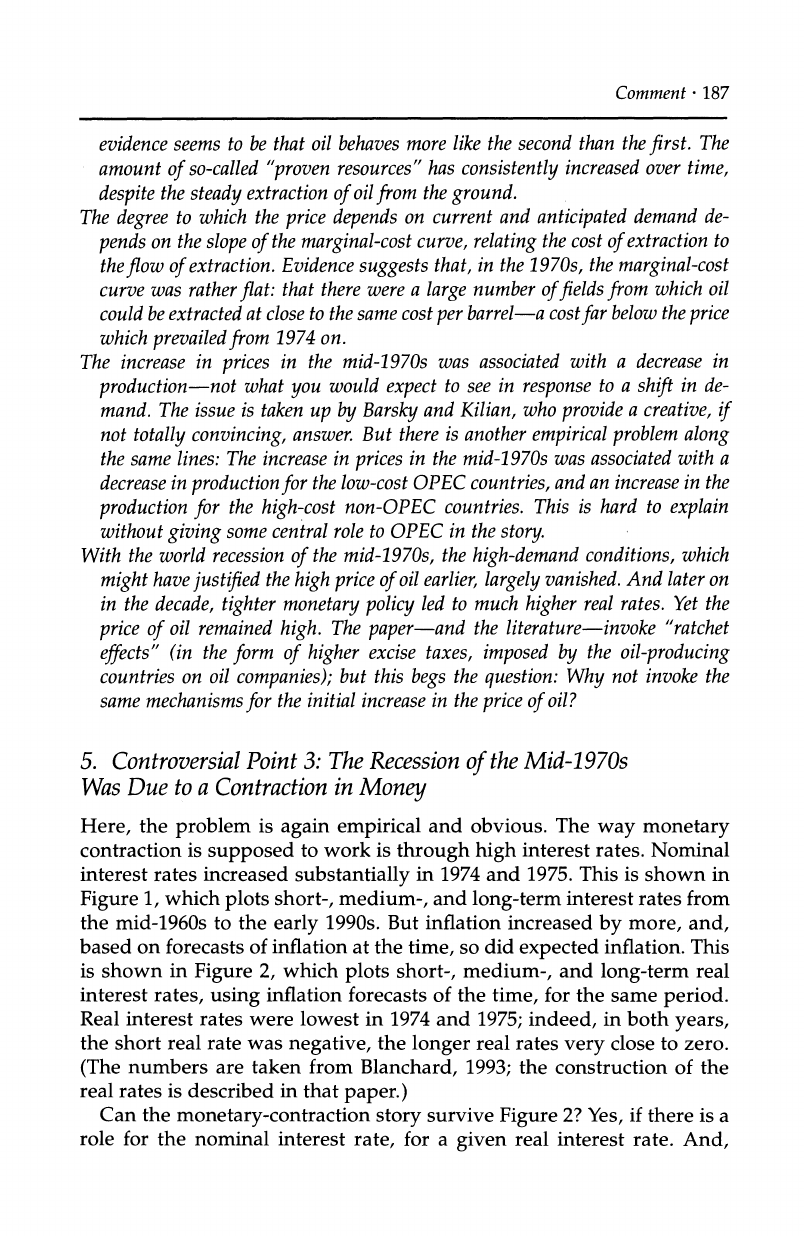

4.2

WORLDWIDE CHANGES

IN

LIQUIDITY

The

changes

in

monetary policy

indicators

in the 1970s

in

the

United

States,

and indeed

in

many

other OECD

countries,

were

accompanied

by unusually large swings

in

global liquidity.

One indicator of

global

liquidity

is world

money growth.

We focus on world

(rather

than

simply

U.S.)

monetary growth,

both because

the

prices

of

oil

and

non-oil com-

modities are

substantially

determined

in

world

markets,

and

because-

despite

its

origins

in

the U.S.-the

monetary expansion

in

the

early

1970s was

amplified

by

the

workings

of the international

monetary sys-

tem,

as

foreign

central banks

attempted

to stabilize

exchange

rates

in

the

1968-1973

period.

The

counterpart

of the

foreign-exchange

intervention

in

support

of the dollar was the

paid

creation of domestic credit

in

all of

the

large

economies

(see

McKinnon,

1982;

Bruno and

Sachs, 1985;

Genberg

and

Swoboda,

1993).

Figure

4a and b

show

a

suitably updated

data set for

GNP-weighted

world

money growth

and

inflation,

as defined

by

McKinnon

(1982).

There is evidence

of

a

sharp

increase

in

money growth

in

1971-1972 and

in

1977-1978

preceding

the two

primary stagflationary episodes

in

Table

1.

The increase

in

world

money

growth

is followed

by

a substantial

rise

in

world

price

inflation

in

1973-1974 and in

1979-1980

(see

Figure

4b).

The

data also

show

a

third

major

increase

in

world

money-supply

growth

in

1985-1986.

This does

not

pose

a

problem

for

the

monetary

explanation

of

stagflation,

because

1985-1986 is

fundamentally

different

from

1973-1974 and

1979-1980.

The coincidence of

substantial

money

growth

and low

world

inflation

constitutes

a

partial

rebuilding

of real

balances

following

the restoration

of the

commitment to

low

inflation.9

9.

This is

precisely

the standard

interpretation

of the

patterns

of

inflation and

money

growth

that

have

been

documented for the

period

following

the

monetary

reform that

ended the

German

hyperinflation

(see

Barro, 1987,

p.

206,

Table

8.1).

152

-

BARSKY

& KILIAN

Figure

4

MEASURES OF WORLD

LIQUIDITY

(a)

World

Money

Growth: Ten

Industrial

Countries

(b)

World Price Inflation: Ten Industrial Countries

15

20

15

...I

10

l

U)

0

-5

1960

1965

197

1975

1980

1985

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 19

(c)

Growth

of

World

Real Balances:

Ten

Industrial Countries

15

10

5

20

-10

-15-

1960

1965 1970

1975

1980

1985

Source:

Inflation

and

money

are

GNP-weighted

growth

rates

per

annum

as

defined

by

McKinnon

(1982,

pp.

322),

based

on

IFS

data

for

1960.1-1989.4.

We

now

turn

to

the

United

States,

where the

monetary expansions

of

the

1970s

originated.

Figure

5

shows

that

U.S.

liquidity

followed a

pat-

tern

similar

to

that

of other

industrial countries.

Figure

5a

shows

two

large

spikes

in

money growth

in

1971-1972

and in

1975-1977

that

pre-

ceded

two

episodes

of

unusually

high

inflation

in

the

GDP

deflator

in

1974 and

in

1980

(see

Figure

5b)

and

that

coincided

with

two

episodes

of

significantly

negative

growth

in

real

money

balances

in

1973-1974

and

1978-1980

(see

Figure

5c).

Figure

5c

also

shows

evidence

of

a

rebuilding

of

real

balances

(and

possibly

of the

financial

deregulation)

after

1980.

Additional

evidence

of

excess

liquidity

in

the

1970s is

provided

by

the

behavior of

the U.S.

real

interest

rate.

Figure

5d shows

that 1972-1976

and

1976-1980

were

periods

of

abnormally

low

real interest

rates,

followed

by

unusually high

real interest

rates

in

1981-1986.

This

pattern

is

consistent

with the

view that

the excess

money

growth

in

the

early

and

mid-1970s

depressed

ex

ante

real interest

rates

via a

liquidity

effect

and

further

depressed

ex

post

interest

rates

by

causing

unanticipated

inflation.

The

evidence

in

Figure

5d

also is consistent

with

the

view

that the Fed

in

the

1970s followed

an interest-rate

rule

that was

more tolerant

of

inflation

than would

have been

consistent

with a

Taylor

rule

as estimated

over

the

Do We

Really

Know

that Oil Caused

the Great

Stagflation?

*

153

Figure

5 MEASURES

OF

U.S.

LIQUIDITY

(a)

U.S.

Money

Growth

(b)

U.S.

Deflator Inflation

10

03

ao

cL

8

6

4

2

1

a)

0

a)

0-

OE

n

. .

1960 1965

1970

(c)

Growth

of U.S.

Real

Balances

.. ..

10

5

0

-5

1960 1965 1970 1975 1980 1985

1975 1980

1985

(d)

U.S. Real Interest Rate

I I I I

-

5-

0

^vH

^

.A.

i

1960 1965 1970

1975 1980 1985

Source:

(a)

Based on

DRI

series FM2.

(b)

Based on DRI series GDPD.

(c)

Based on DRI

series

FM2 and

PRXHS.

(d)

Based on DRI series FYGM3 and PRXHS.

Volcker-Greenspan period

(see

Clarida, Gall,

and

Gertler,

2000).

Finally,

the

timing

in

Figure

5d contradicts the view that oil

shocks were

responsi-

ble

for the low ex

post

real interest rates. Real

interest rates were

negative

during

1973,

after the evidence of

excess

money growth,

but

well before

the two

major

oil

price

increases.

In

fact,

the 1973-1974 and

1979-1980 oil

price

increases were followed

by

a

rise

in

ex

post

real interest

rates.

4.3

MOVEMENTS IN

OTHER

INDUSTRIAL COMMODITY

PRICES

An

important

additional

piece

of evidence that

has received

insufficient

attention in

recent

research is

the

sharp

and

across-the-board

increase

in

industrial

commodity prices

that

preceded

the

increase

in

oil

prices

in

1973-1974

(see

Figure

6).

These

increases occurred

as

early

as

1972,

well

before

the

October

War,

and

are too

broad-based

to

reflect

supply

shocks

in

individual

markets.

They

are,

however,

consistent

with

a

picture

of

increased

demand

driven

by

the

sharp

increase

in

global

liquidity

docu-

mented in

Figure

3.

There is

significant

evidence that

poor

harvests

caused food

prices

to

soar

in

the

early

1970s

(see

Blinder,

1979).

Our data

set

deliberately

rc

a)

03

03

c)

0-

,

I

LA

-

154

*

BARSKY

&

KILIAN

Figure

6

NOMINAL PRICE INDEXES

FOR CRUDE OIL AND FOR

INDUSTRIAL

COMMODITIES, JANUARY

1948 TO

JULY

2000

-

1

-

I I I

I

I

I

I

I

I

I

1950

1955

1960 1965 1970

1975

1980

1985

1990 1995

2000

Source: All

data are

logged

and de-meaned.

The

commodity

price

index

excludes oil

and

food. The index

shown is an index

for industrial

commodity

prices

(DRI

code:

PSCMAT).

Virtually

identical

plots

are

obtained

using

an

index for sensitive materials

(DRI

code:

PSM99Q).

The oil

price

series is defined as

in

Figure

1.

excludes

food-related commodities.

Instead,

we focus on

industrial

raw

materials.

Commodities such as

lumber,

scrap

metal,

and

pulp

and

pa-

per,

for

which

there

is no

evidence

of

supply

shocks,

recorded

rapid

price

increases in the

early

1970s

(see

National

Commission on

Supplies

and

Shortages,

1976).

For

example,

the

price

of

scrap

metal

nearly

dou-

bled

between October

1972

and

October

1973,

and

continued to rise until

early

1974,

to

nearly

four times its initial level. The

price

of lumber

almost

doubled between

1971 and

1974,

as

did

the

price

of wood

pulp.

These

commodity price

data

paint

a

picture

of

rapidly rising

demand for

all

commodities

in

the

early

1970s.

It

is

interesting

to

note

that a

similar

increase

did

not

occur

in

oil

prices

until

late 1973.

Similarly,

the

1979 increase

in

oil

prices

was

preceded by

a

boom

in

other

commodity prices,

consistent with

the evidence of mone-

tary

expansion, although

the

commodity price

increase is of lesser

magni-

tude.

In

fact,

a

striking empirical regularity

of the data in

Figure

6 is that

Do We

Really

Know that Oil Caused

the Great

Stagflation?

*

155

increases

in

other

industrial

commodity prices

tended to

precede

in-

creases

in

oil

prices

over the 1972-1985 OPEC

period

(and

similarly

for

decreases).

This fact is

evident for

example

in

1972,

1978, 1980,

1983,

and

1984.

A

natural

question

is

how

the

monetary

explanation

of

stagflation

proposed

here

can be reconciled

with

the

delayed response

of oil

prices

relative

to

other

industrial commodities.

The

explanation

appears

to

be

that,

unlike other

commodity

transactions,

most

crude-oil

purchases

until the

early

1980s did

not

take

place

in

spot

markets,

but at