2015

Learning While Earning:

The New Normal

Anthony P. Carnevale | Nicole Smith | Michelle Melton | Eric W. Price

$

$

Center

on Education

and the Workforce

McCourt School of Public Policy

Learning While Earning:

The New Normal

2015

Contents

The rise in the number of working learners is a

natural evolution of our work-based society.

Early work experience forms good habits and

helps students make career connections.

More attention should be paid to the

pathways from education to work.

Four rules are important for understanding the

connections between postsecondary programs and careers.

College enrollment has increased from

2 million to 20 million in 60 years.

Working learners are more concerned about enhancing

résumés and gaining work experience than paying for tuition.

Young working learners (16-29) make very dierent decisions

compared to mature working learners (30-54) when it comes to

majors selected, hours worked, and career choices.

Nearly 60 percent of working learners are women.

Young working learners are disproportionately white, while

mature working learners are disproportionately African-American.

Mature working learners are more likely to

be married with family responsibilities.

Mature working learners are concentrated in open-admission

community colleges and for-prot colleges and universities while

young working learners tend to go to more selective institutions.

Young working learners are more likely to select

humanities and social sciences majors while mature

working learners select healthcare and business.

Mature working learners are more likely to be

working full-time, but over a third of young working

learners work more than 30 hours per week while enrolled.

8

6

10

13

THE RISE OF

WORKING

LEARNERS

WHO ARE

WORKING

LEARNERS?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

PORTRAITS OF

WORKING LEARNERS

INTRODUCTION

SUMMARY

SUMMARY TABLE

14

20

24

14

15

18

19

20

21

24

27

28

30

32

33

35

Contents

Mature working learners earn

more than young working learners.

Working learners have less student

debt than students who do not work.

Forty-ve percent of young working learners earn

200 percent of the poverty treshold ($23,540) or less.

After graduating, working learners are upwardly mobile

and more likely to move into managerial positions.

Working learners need stronger ties between the

worlds of work and education. Among all programs for

working learners in postsecondary institutions, learning

and earning is the common currency.

The data system that connects postsecondary elds of study

and degrees with labor market demands is still a work in progress.

Available career counseling in colleges is very limited and is

rarely based on any data about the economic value of college majors.

Tying career outcomes to elds of study

is still an afterthought in postsecondary policy.

The traditional Bachelor’s degree-centric model has

limited utility in a world focused on workforce development.

Working learners need competency-based postsecondary

curricula that drill down below overall degree attainment and

programs of study to the cognitive and non-cognitive competencies

required for them to move along particular occupational pathways.

The relationship between postsecondary elds of study

and careers is only a rough proxy for a deeper and more

dynamic relationship between competencies taught in

particular curricula and competencies required to

advance in particular occupationally based careers.

The overlap between postsecondary education

and career learning is a huge uncharted territory.

Existing policies inside and outside the postsecondary policy

realm could be altered to be of greater assistance to working learners.

APPENDIX:

DATA SOURCES

REFERENCES

39

43

45

48

47

POLICY

IMPLICATIONS

60

67

50

51

53

54

54

56

57

58

59

W

e would like to express our gratitude to the individuals and organizations whose generous

support has made this report possible: Lumina Foundation (Jamie Merisotis and Holly

Zanville), the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation (Daniel Greenstein and Jennifer Engle), and

the Joyce Foundation (Matthew Muench). We are honored to be partners in their mission of

promoting postsecondary access and completion for all Americans.

Many have contributed their thoughts and feedback throughout the production of this report.

We are grateful for our talented designers, meticulous editorial advisers, and trusted printers

whose tireless efforts were vital to our success.

In addition, the Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce staff was

instrumental to production of this report, from conceptualization to completion. Our thanks

especially go to the following individuals:

• Jeff Strohl for research direction;

• Andrea Porter for strategic guidance;

• Megan Fasules, Artem Gulish, Andrew R. Hanson, and Tamara Jayasundera

for data compilation and analysis, and for fact-checking;

• Ana Castanon, Monet Clark, Victoria Hartt, Hilary Strahota,

and Martin Van Der Werf for communications efforts,

including design, editorial, and public relations; and

• Coral Castro and Joseph Leonard for assistance

with logistics and operations.

We would also like to thank ACT Foundation for its support of this report. We especially

thank Tobin Kyte and Marcy Drummond for providing insight to the report and fostering a

partnership between our organizations. We support ACT Foundation’s mission as it advances

solutions for working learners to integrate working, learning, and living to increase quality of

life and achieve education and career success.

We also wish to thank Dr. Felicito “Chito” Cajayon, the vice chancellor of workforce & economic

development at the Los Angeles Community College District; Milo Anderson; and Scott Ralls,

the president of Northern Virginia Community College; his executive assistant Corinne Hurst;

and Kerin Hilker-Balkissoon, the executive director of college and career pathways at Northern

Virginia Community College. All helped the authors contact mature working learners for this

report.

Finally, we sincerely thank the working learners who gave so generously of their time to help

shape the tone of the project in its formative stages. We have a greater appreciation for the

challenges faced by working learners and the opportunities they have. This report benefited

enormously from our conversations with them.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of Lumina

Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Joyce Foundation, ACT Foundation or their officers or employees.

Acknowledgements

Portraits of Working Learners

Working while learning is now the accepted pathway to education

and training for both young and mature working learners.

When working with aggregate data, it’s easy to lose sight of the voices and experiences of the people being studied.

As part of the research for this report, the authors interviewed a number of actual working learners — some of whom

were members of the ACT Foundation Working Learner Advisory Council — and utilized their personal experiences

and stories to illuminate the report and to develop policy proposals that would satisfy their needs. The following are

some of the individuals who helped to provide insight into the lives of today’s working learners:

H

eather Jones, a mature working learner, is enrolled part-time at a two-year public technical

college. She works full-time at the corporate oce of a large bank. She is taking classes for self-

enrichment and is not enrolled in a degree-granting program. She earned a Bachelor’s degree from a

four-year private doctorate-granting college 15 years ago.

Hometown: Burbank, Calif.

Heather Jones on working learner needs:

“Orientation days. How great that would be if there was something oered specically for

non-traditional aged students! You know it would be designated a certain name; they would

have specic resources, and specic contacts.”

Hometown: Lake Placid, Fla.

M

organ Lamborn, a young working learner, is enrolled part-time in a

Master of Business Administration program at a four-year public doctorate-

granting university where she works full-time as an admissions ocer.

Morgan Lamborn on working learner time constraints:

“Time is the biggest challenge. There are never enough hours in the day. So working on

my Master’s right now is a lot; it’s being pulled in 62 directions at once, every single day.”

T

hierry Pierre-Charles, a young working learner, is enrolled full-time in a Bachelor’s

degree program at a four-year public doctorate-granting university. His self-designed

major is in biomedical science and policy, with a focus on pre-medical studies and scientic

studies. He works part-time as a transition specialist assisting people with disabilities.

Hometown: Miramar, Fla.

Thierry Pierre-Charles on working learner isolation:

“I knew that I would end up having to work, because my parents weren’t in a position to support me. It kind of

impacts you mentally because you really don’t have too much social interaction — you know you can’t go out and have

fun. But the only reason I even kept doing it is because I didn’t have anything else to fall back on.”

Portraits of Working Learners

L

andon Taylor is a young working learner. He is married and has two children and is enrolled

full-time in a Bachelor’s Degree program at a four-year public non-doctorate-granting university.

His major is public relations and advertising. He works part-time during the day for a technology

consulting rm as a business development coordinator, and part-time in the evening as

a server at a restaurant.

Hometown: Oakland, Calif.

Landon Taylor on the motivations of working learners:

“Society tells you that if you have kids while you’re in school, your life is over — you’ve got to basically give up your

dreams. I believe the exact opposite. I think your children should inspire you to do great things. And that’s what

they’ve done. I can’t wait till when they’re older, to be able to tell them everything that we went through to make

sure that they had a great life.”

M

ilo Anderson, a mature working learner, is enrolled part-time in a certicate program

at a two-year public technical college. His focus is in business administration. He earned a

Bachelor’s degree from a four-year public non-doctorate-granting university 10 years ago.

Hometown: Canoga Park, Calif.

Milo Anderson on the stigmas faced by working learners:

“There is a stigma to going back to college. It’s sort of frowned upon. I think what I’d like to see, as more of a

general change in mindset, is more acceptance of the fact that education is a lifelong process. I’m going back

to school and I can see people’s expression change, like, ‘Oh. So, you’re 31 and still not doing anything with

your life?’ That’s the kind of negative mindset I’d like to see shifted.”

Y

adira Gurrola, a young working learner, is enrolled full-time in a Bachelor’s degree program

at a four-year public college. Her major is social work and she is also pursuing a certication to

become a pharmacy technician. She works part-time at a discount retail superstore as a store manager,

monitoring cash registers and the service desk, and assisting the pharmacy.

Hometown: Scottsblu, Neb.

Yadira Gurrolla on working learner perseverance:

“It feels good to know that I can pay for my phone. I can pay for my gas. I can pay for my clothes. I can pay for

everything that I need. This is, I guess, in my heart. This is me; this is my story. I know what my next step is. As

long as I can get there and keep going on, that’s kind of my ambition.”

1 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data,

2012-2013.

F

or decades, the popular conception of a

college student in this country has been

the full-time residential nancially dependent

student who enrolls in a four-year college

immediately after graduating from high school.

But that student has not been the norm at U.S.

postsecondary institutions for more than 30

years. Such students exist but they are greatly

outnumbered by working learners: students

who balance learning in college with earning

a paycheck.

In the United States today, nearly 14 million

people – 8 percent of the total labor force

and a consistent 70 percent to 80 percent of

college students – are both active in the labor

market and formally enrolled in some form of

postsecondary education or training.

1

These

programs include degree-granting programs,

such as Associate’s and Bachelor’s degree

programs, non-degree granting programs, and

certication and vocational training programs.

In the 21st century economy, skills have become

the most important currency in job markets.

Today, workers need the right postsecondary

preparation to gain a foothold and prosper

in the labor market, employers need highly

skilled postsecondary talent in order to remain

competitive, and communities need both a

highly skilled workforce and a competitive

business sector in order to build attractive

places to live, work, and study.

In this report, we examine the students who

are combining work with ongoing learning.

We nd that:

• Going to college and working while

doing so is better than going straight

to work after high school. Many people

argue that it’s better to go to work than to go

to college, particularly from the perspective

of lost potential wages while in school.

Our ndings show clearly that students

who complete college degrees while working

are more likely over time to transition to

managerial positions with higher wages than

people who go straight into full-time work

after high school.

• Working while attending college hurts

disadvantaged students the most.

This is because working learners of lower

socioeconomic status are more likely to work

full-time and attend under-resourced open-

admission community colleges. There is a

widespread consensus that working too much

while enrolled in a postsecondary program

hurts one’s chances of completing it. It is not

clear, however, whether low completion rates

among working learners employed full-time is

due to working more, having access to fewer

Summary

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 11

2 Working in high school is bad for student outcomes but outcomes are much more complicated for college students. For those

who complete a degree, working while in college can yield many long-run advantages, especially if students work in a field directly

related to their course of study.

3 Bailey et al,. Redesigning America’s Community Colleges. 2015. Working in field is especially relevant for fields of study that have direct

ties to occupations such as STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) and healthcare, or Associate’s degrees

in applied sciences. Carnevale et al., Certificates, 2012, show that working in field adds 37 percent to wages of workers with a

postsecondary vocational certificate.

4 See Table 1.

educational and support services, the relevance

of the program to their career, or other barriers

associated with socioeconomic status.

2

• Working and learning simultaneously

has benets, especially when students

work in jobs related to what they study.

Work experience also becomes an asset that

working learners carry with them as they enter

the full-time job market, accelerating their

launch into full-time careers.

3

• Most students are working. Students

are workers and workers are students.

From 1989 to 2008, between 70 percent and

80 percent of undergraduates were employed.

By 2012, that share declined to 62 percent due

to the job losses associated with the 2007-

2009 recession.

4

Students work whether they

are in high school or college; whether they

are rich, poor, or somewhere in between;

whether they are young and inexperienced

or mature and experienced.

• One-third of working learners are 30

or older. Mature working learners (ages

30-54) primarily comprise workers who

have a postsecondary credential but are

upgrading their credentials to keep up with

the requirements of their jobs, to earn a

promotion, or to retrain for a new career.

• More people are working full-time

while in college. About 40 percent of

undergraduates and 76 percent of graduate

students work at least 30 hours a week.

About 25 percent of all working learners

are simultaneously employed full-time and

enrolled in college full-time. Adding to their

stress, about 19 percent of all working learners

have children.

• You can’t work your way through

college anymore. A generation ago,

students commonly saved for tuition by

working summer jobs. But the cost of college

now makes that impossible. A student working

full-time at the federal minimum wage would

earn $15,080 annually before taxes. That isn’t

enough to pay tuition at most colleges, much

less room and board and other expenses.

• Students are working and taking out

more loans to pay for college.

The nation has yet to gure out how to pay

for this new stage in the transition from youth

dependency to adult independence and family

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

12

formation. Public funding of postsecondary education at both the state and federal

levels is declining. This trend has resulted in the rapid increase in the amount of

outstanding student loan debt, from $240 billion in 2003 to $1.2 trillion today.

5

Policy implications

• Working learners need stronger ties between the world of work

and the world of education. In spite of the centrality of career goals as the

motivation to get a college degree, students are left largely on their own to connect

their postsecondary education choices to an increasingly complex set of career

options.

6

• To improve the connections between work and learning, federal

and state policymakers should fund postsecondary education, in

part, based on performance measured by labor market outcomes.

Historically, the public has funded postsecondary education and training

programs based on enrollment. In this system, regionally-accredited institutions

receive public funding in proportion to the size of their student body. However,

many states have recently embraced performance-based funding models, under

which institutions are awarded for achieving outcomes measured by outcome

standards set by policymakers.

• Policymakers should also invest in competency-based education

programs that teach skills with labor market value. Mature working

learners in particular have developed competencies through work that are not

recognized by postsecondary education and training institutions because they

were not learned in a classroom environment. Competency-based education

programs recognize and award credit for prior learning, which allows working

learners to learn eciently and potentially to accelerate their progress through

education and training programs.

5 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the Federal Reserve

Bank of New York, 2003-2014.

6 Bailey et al., Redesigning America’s Community Colleges, 2015.

Summary Table

* A small share of working learners (3%) is over 55 years old and is generally excluded in the analysis of this report.

** The federal poverty line varies by household size. In 2015, an income of $23,540 represents 200 percent of the federal poverty line for a single individual.

Wages above $42,000

per year

Between $7,500 and

$42,000 per year

Less than $7,500 per year

9% 42%

58% 46%

33% 12%

Wages after

completing

Bachelor’s degree

Young working learner,

16-29 years old

Mature working learners,

30-54 years old*

Wages above $42,000

per year

Between $7,500 and

$42,000 per year

Less than $7,500 per year

10% 8%

67% 53%

23% 39%

Wages while

enrolled

Share 67% 33%

Share with children 20% 61%

Sex 56% women 59% women

40% 76%Share working full time

Bachelor’s degree Certificate/Associate’s degreeCommon degree program

Four-year colleges

Community colleges and

for-profit colleges

Institutional sector

Disproportionately white

Disproportionately African-

American

Race/ethnicity

Common occupations

26% food and personal

services occupations

6% in managerial occupations

12% food and personal

services occupations

17% in managerial occupations

Common majors

Social sciences, humanities,

business, and other

applied fields

Healthcare, business, and

other applied fields

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Review, 2012 and

National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health waves 3 and 4, 2001-2009.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

14

The rise in the number of working learners is a natural evolution

of our work-based society.

Work always has been, and continues to be,

a central component of American culture.

Americans work more hours than anyone else

in the developed world. Work provides income

that is the primary means to access the goods

and services necessary for a middle-class

standard of living, but it is more than that.

The jobs that individuals perform are a

central part of their identity.

Work used to be the primary means of nancing

a college education. In the 1950s, college

students represented a small share of the

population and many college students nanced

their tuition by working summer jobs. Since

then, going to college has become much more

widespread – and much more expensive. The

number of college students has increased from

2.4 million in 1949 to 20 million in 2014.

7

The lockstep march from school to work no longer

applies for a growing share of Americans. Many

young adults are taking longer to launch their

careers: the shift from a high school-centered

economy to a postsecondary-centered economy

has added a new phase to the lifecycle. In the

industrial economy high school was enough.

Nowadays one goes nowhere after high school

unless he or she gets at least some college.

8

On

average, because of the new postsecondary human

capital requirements for formal learning and work

experience, the age at which young workers reach

the median wage has increased from 26 to 30.

9

In

other words, the period of transition from youth

dependency to adult independence has grown

from seven to 11 years.

That kind of career bootstrapping is more

visible than ever on campuses. Not only do

colleges include growing numbers of students

who need work (working learners), but more

and more experienced workers who also need

college (learning workers). The transition

into a career is no longer linear. The system

of education for youth leading to informal

learning on-the-job has been replaced by

an expectation of lifelong learning and the

continuous upgrading of skills required to adapt

to new workplace technologies and evolving

occupational structures.

At the same time, the summer job market

has collapsed. In the 1970s, more than half

of youth in their late teens were employed in

7 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics’

Digest of Education Statistics tables, 2013.

8 At best, 20 percent of high school educated men have access to middle-class careers with what is left of the old industrial

career track. See Carnevale et al., Career Clusters, 2011.

9 Carnevale et al., Failure to Launch, 2013.

Introduction

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 15

summer jobs; today, only 30 percent are.

10

So

the old picture of students working and saving

all summer so they can study full-time during

the school year is now quite rare.

A persistent question for parents and educators

has been whether work harms educational

performance or expectations for further

education. The general answer has been

that working more than 15 to 20 hours per week

can harm academic performance and educational

aspirations, especially among

high school students.

11

But these ndings often

rely on heavily descriptive data. More nuanced

analyses suggest a more complicated picture.

Early work experience forms good

habits and helps students make career

connections.

The eect of work on students depends on the

student and the work. Work helps pay living costs

in high school and some share of educational

costs after high school. In general, work — even

menial work — promotes skills such as time

management, communications, and conict

resolution, as well as many other soft skills

necessary for success in the workforce. Work can

also be a meaningful alternative entry into the

adult world, providing an escape into relevance

10 Desilver, “The fading of the teen summer job,” 2015.

11 Dundes and Marx, Balancing Work and Academics in College, 2006

Internships. Half of graduating

college seniors report having

worked as interns.

T

he Economic Policy Institute estimates there are

about 2 million interns in the U.S. labor force (1.3

percent of the 155 million workers in the labor force).

Internships are tailored mostly to four-year college

students while they are enrolled or shortly after

they graduate and enter the full-time labor market.

Colleges and universities typically award academic

credit for internships and frequently match students

to internships and provide oversight of the intern-

employer relationship. Roughly half of college seniors

nationally said they completed an internship while

enrolled, suggesting that roughly one million college

students are employed as interns.

Internships provide on-the-job training and relevant

work experience that prepare future workers for

occupations in a particular industry or career field.

Interns also acclimate themselves to a professional

setting; acquire letters of recommendation for

future entry-level jobs and graduate-level programs

of study; and form professional networks they can

potentially leverage into high-paying jobs later in their

careers. Internships also serve as an opportunity to

test whether particular career fields are of interest

to the interns at minimal cost to themselves or their

employers.

Evidence shows that internships pay off in the long

run. The starting annual salary for college graduates

who completed a paid internship was $52,000,

compared to $36,000 for those who completed an

unpaid internship and $37,000 for those who did

not complete an internship. Furthermore, the share

of college graduates who received a job offer was 63

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

16

from the abstract grinding rigors of schooling.

Work can also be a personal and occupational

exploration connecting individual interests,

values, and personality with academic elds of

study leading to particular careers.

12

But the eects of work dier by student

characteristics both in high school and even more

so in college. Low-income students, especially low-

income African Americans and Hispanics, tend to

experience the more negative eects of working

on their educational achievement and educational

attainment. This appears to be the result of

a lack of counseling, social capital, and other

supports that are typically associated with a higher

socioeconomic status or more selective colleges.

13

The eects of work and learning also depend on

the nature of the work. A job is more powerful as

an educational tool when it provides exploratory

learning that supplements or complements

a student’s eld of study. This is crucial in

graduate education, where elds of study are

most tightly tied to careers. It is more complex

at the baccalaureate level, where educational and

career exploration is still fresh, especially among

younger students with less work experience. A job

is most likely to be complementary to academic

skills for the 80 percent of baccalaureate majors

pursuing career-related majors such as science,

technology, engineering, and mathematics

(STEM), business, education, and healthcare.

14

12 Hobson, Is Work Good for Your Health and Well-Being?, 2007

13 Carnevale et al., Separate and Unequal, 2013

14 Carnevale et al., The Economic Value of College Majors, 2015

percent for those who completed a paid internship,

compared to 37 percent for those who completed an

unpaid internship and 35 percent for those who did

not complete an internship.

†

The benefits are not so clear, however, when the

internships are unpaid. Many students engaged

in disciplines such as politics, policy, arts,

entertainment, and journalism often participate in

unpaid internships as a necessary rite of passage

for entry-level workers. However, there are strong

allegations that these internships are prone to

nepotism and that, because young adults from low-

income family backgrounds cannot afford to take

unpaid positions, their access to careers in these

industries is limited. The Economic Policy Institute

has proposed subsidizing unpaid internships for

students from low-income families through the

Federal Work-Study grant program to address these

concerns. The recent public scrutiny of unpaid

internships has sufficed, in some cases, to encourage

employers to either pay their interns, as the Nation

Institute and Atlantic Media did, or to end their

internship programs altogether, as in the case of

the mass-media company Condé Nast. Under the

assumption that internships are mutually beneficial

to employers, postsecondary institutions, and interns

themselves, these new trends represent a cause for

concern. However, recent evidence questioning the

value of unpaid internships suggests their decline

may not carry a significant negative impact.

† Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis

of data from the National Association of Colleges and Employers, 2013.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 17

Tying learning content to work experience is

more problematic at the Associate’s degree

level. More than half of Associate’s degrees are

Associate of Arts (AA) degrees with no obvious

relevance to specic occupations or industries. But

Associate of Science (AS) or Associate of Applied

Science (AAS) degrees, which have a direct tie

to occupation or industry, comprise a large

share of Associate’s degrees. The same is true of

the 12 million certicates produced every year.

Moreover, substantial shares of programs have

direct connections to industry-based certications

and licenses that provide a “workaday” focus for

college programs and course clusters.

Young and mature working learners’

experiences vary:

• Young working learners are more likely to be

enrolled in baccalaureate programs at colleges

than mature working learners, who are more

likely to be in certicate programs or employer-

sponsored training.

• Young and mature working learners enroll in

dierent majors and elds of study. Young

working learners are disproportionately

enrolled in the humanities and social

sciences, while mature working learners are

disproportionately enrolled in career-oriented

majors, such as healthcare and business.

• Mature working learners have more work

experience, possess a clearer concept of their

future career goals, and are more likely to

enroll in career-oriented majors.

Internships, externships, and work-study

programs that connect students to real job

experiences as well as professional contacts are

the new norm for college-goers. In the hope of

gaining a competitive edge and enhancing their

résumés, many working learners seek temporary

work positions while enrolled. Working learners

who complete college degrees while working are

more likely to transition to managerial positions

over time than workers who have not completed

college degrees while working.

This suggests that the marketplace rewards

those with higher credentials and increasingly

requires additional skills before employees

can be promoted. In addition to moving to

managerial positions, working learners also have

increased mobility as a whole and are more likely

to transition to dierent occupations after they

complete their education compared to workers

who do not complete degrees while working.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

18

More attention should be paid to the pathways from education to work.

The growing connection between work and

learning needs to be a serious subject for policy

discussion and a key performance metric in

assessing postsecondary outcomes. Ultimately,

of course, in a modern republic such as our own,

the higher education mission is to empower

individuals to live fully in their time. But it’s hard

for people to live fully in their time if they are

living under a bridge. It’s hard to be a lifelong

learner if one is not also a lifelong earner.

Yet, while the connection between postsecondary

education and the economy has moved to the

center of the national policy dialogue, and

as data systems that connect postsecondary

programs with careers become more integrated,

our current ability to articulate and build

curricula and counseling systems that honor

these relationships is woefully inadequate.

Transparency between postsecondary programs

and labor markets has become more important

because of the growing diversity among

postsecondary programs of study, credentials,

and modes of delivery that are aligned with an

increasingly complex set of career pathways.

• The number of career elds identied by the

U.S. Census Bureau increased from 270 to 840

between 1950 and 2010;

15

• The number of colleges and universities

grew from 1,850 to 4,720 between 1950

and 2014;

16

and

• The number of programs of study oered

by postsecondary education and training

institutions grew from 410 to 2,260 between

1985 and 2010.

17

In this new environment, programs and

curricula matter more and institutions matter

less. In economic terms, the relationship between

the college a worker attended and the career

that person chooses has become weaker and

the impact of eld of study on career prospects

has become stronger. The economic value of

postsecondary education and training has less to

do with institutional brands and more to do with

the growing dierences in cost and value among

15 Wyatt and Hecker, Occupational Changes During the 20th Century, 2006; BLS, 2015.

16 National Center for Education Statistics, Digest of Education Statistics, table 317.10.

17 National Center for Education Statistics, “Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System,” n.d.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 19

an expanding array of programs in particular

elds of study. Degrees and other postsecondary

credentials have multiplied and diversied: from

traditional degrees measured in years of seat

time; to micro-credentials that take a few months;

to boot camps, badges, stackable certicates,

noncredit programs, and MOOCs (massive open

online courses) that take a few weeks; to test-

based industry certications and licenses based

on proven competencies completely removed

from traditional classroom training.

The fragmentation in programs and providers

reects a parallel fragmentation in the

education and training needs of the modern

postsecondary student body.

Four rules are important for understanding the connections between

postsecondary programs and careers.

The new relationship between postsecondary

programs and the economy comes with new rules

that require much more detailed information on

the connection between individual postsecondary

programs and career pathways:

• Rule 1. On average, more education yields

more pay. Over a career, high school graduates

earn $1.3 million; Bachelor’s degree holders

earn $2.3 million; PhD holders earn $3.3

million; and professional degree holders earn

$3.7 million.

18

• Rule 2. What a person makes depends on what

that person takes. A major in early childhood

education pays $3.3 million less over a career

than a major in petroleum engineering.

• Rule 3. Sometimes less education is

worth more. A one-year information-

technology certicate holder earns up to

$72,000 per year compared with $54,000

per year for the average Bachelor’s degree

holder. Thirty percent of Associate’s degree

holders make more than the average

four-year degree holder.

• Rule 4. Programs are often the same in

name only. Programs and college majors

have dierent values at dierent institutions

depending on the alignment between particular

curricula and regional labor market demand, as

well as on dierences in program quality.

18 Carnevale et al., The Economic Value of College Majors, 2015.

College enrollment has increased

from 2 million students to 20 million

students over 60 years.

The growth in the postsecondary student body

is partly a function of the growing demand for

educated workers and the reality that jobs and

the opportunity to earn middle-class wages are

increasingly tied to postsecondary credentials.

The number of students enrolled in postsecondary

institutions increased from 2.4 million in 1949 to

20 million in 2010, from 60 percent to 68 percent

of high school graduates.

19

Much of the growth

since 1973 can be attributed to rising demand

for college graduates in the labor market and

the dierence in wages that could be earned by

college graduates over high school graduates.

As the U.S. economy has restructured over the

past few decades, the need for skilled workers

has accelerated. A comparatively widespread and

diverse cross section of American youth and older

students has recognized and responded to the

market demand for higher skills by enrolling in

postsecondary institutions.

Much of the postsecondary enrollment

growth witnessed over the past decade is

attributable to the rise in enrollment of

older students.

As economic change accelerated in the 1980s and

1990s, colleges began to attract an increasing

19 Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Center for Education Statistics’ Digest of Education Statistics,

Tables 302.10 and 303.10, https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/.

The Rise of Working Learners

Access to a support system that both removes

traditional barriers and provides a nancial

safety net appears to be one of the most

signicant factors aecting educational and

workforce outcomes for working learners.

Indeed, an ideal holistic support system for

working learners, provided in partnership

by a postsecondary institution and a private

company to increase postsecondary retention

and attainment rates, could include the

following components:

• Convenient learning options, such as

distance learning or online courses;

• Provision of child care;

• Aordable transportation options;

• Employment partnership agreements;

• Access to healthcare insurance;

• Paid sick, maternity, and paternity leave;

• Financial literacy and wealth-building

information and retirement/investment options;

and, most importantly,

• Tuition assistance.

Employee Tuition Assistance Programs

make up an important financial safety net

that supports working learners.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 21

share of older students as well as the traditional

18- to 24-year-old cohort. In fact, students over

the age of 25 accounted for more than 40 percent

of the enrollment growth between 2000 and

2011.

20

Today, most undergraduate students –

consistently between 70 percent and 80 percent

of undergraduates enrolled in U.S. postsecondary

institutions for most of the past 25 years — are

employed (Table 1). Regardless of student

characteristics such as family income, nancial

dependency, enrollment status, type of institution,

age, race, marital status, or other demographic

characteristics, the contemporary “average”

college student works.

Moreover, the attachment of students to the labor

market is anything but marginal. Data from the

early 1990s to the present consistently show that

students work an average of around 30 hours per

week. At least a quarter of all students – and about

a fth of all students who enroll on a full-time

basis – are also employed full-time while enrolled.

Working while enrolled in college is not a

new phenomenon and does not appear to be a

temporary response to cyclical economic factors.

Rates of student employment rose steadily

during the 1970s and 1980s and have held steady

20 National Center for Education Statistics. Digest of Education Statistics, 2013, (2015), Chapter 3.

We identify tuition assistance as being the

most important support component because,

in the absence of nancial support from an

external source, such as need-based grants,

parental support, or student loans, the majority

of workers simply could not aord the cost

of tuition and fees for postsecondary

enrollment each semester.

Over the past 20 years, businesses have

begun to rethink their position on tuition

assistance programs (TAPs) for employees.

While TAPs may be benecial for working

learners, they also benet employers. Workers

who make full use of tuition assistance may

demonstrate productivity above the market

level (i.e. companies that oer TAPs hire more

productive workers to begin with and reduce

costs through decreased employee turnover).

Even if the skills and knowledge gained

through completion of a degree program

ultimately lead to working learner turnover

to the benet of dierent companies, current

employers and rms continue to nd TAPs

to be worth the investment.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

22

since then (Table 1), irrespective of economic

cycles.

21

The U.S. Census Bureau found that

72 percent of students worked in 2011, and

one-fth of all students worked full-time year-

round. The number of weeks employed while

enrolled varies to some degree. For example,

the share of full-time students who work all

or most weeks is 87 percent, compared with

97 percent of exclusively part-time students.

Eighty-nine percent of dependent students work

all or most weeks, compared with 93 percent of

independent students.

22

The share of students working was relatively

consistent in the 1990s and 2000s at between

70 percent and 80 percent. The share working

full-time was also fairly consistent, at between

30 percent and 40 percent. Both have declined

somewhat due to the Great Recession that began

in 2007. The decline since 1996 in the proportion

of working learners who are employed full-time

may mean that the benets of working while

going to college may have topped out as rising

college costs make working a less eective

nancing strategy compared to loans.

21 The proposition that rising demand is entirely responsible for rising student employment is complicated by demographic supply side

factors. For example, the largest gain in employment among students occurred during the 1970s as the baby boomers rushed into the

workforce and onto college campuses at the same time, creating a relative surplus of young workers and a large number of college

students who needed to work, especially prior to the advent of large increases in federal student loans. (Stern and Nakata, Paid

Employment Among U.S. College Students, 1991).

22 Horn and Betktold, Profiles of Undergraduates in U.S. Postsecondary Education Institutions, 1998.

Table 1. In the 1990s and 2000s, the share of Americans working while enrolled in

postsecondary institutions was consistent until it declined following the recession.

2003 - 2004

2007 - 2008

2011 - 2012

1995 - 1996

1992 - 1993

1989 - 1990

29

29

29

30

31

21,072

24,573

18,081

12,328

11,667

10,139

33

32

26

36

34

4030

74

75

62*

79

72

77

Average hours

worked

Share

working (%)

Share working

full-time (%)

Average student debt

(2014$)

Year

Sources: All data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Review, various years; National Center for Education Statistics, 1994;

Cuccaro-Alamin and Choy, Postsecondary Financing Strategies, 1998; Horn and Berktold, Profiles of Undergraduates in U.S. Postsecondary

Education Institutions, 1998; Horn and Nevill, Profiles of Undergraduates in U.S. Postsecondary Education Institutions, 2006; U.S.

Department of Education, 2010; U.S. Department of Education, 2014.

* The decline in the percent of working learners in 2011-2012 is most likely due to severe job losses during the Great Recession.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 23

Working learners are more concerned about enhancing résumés

and gaining work experience than paying for tuition.

Students enter the labor market for a variety of

reasons.

23

Those reasons include to:

• Provide nancial support or pay for

education expenses;

• Gain or maintain useful skills and experience;

• Build or maintain a professional network; or

• Complement and reinforce classroom learning.

College students also work because it’s part of the

culture in which they were raised, because their

parents choose not to nance their education

wholly, or due to other preferences related to

debt, nancial independence, or lifestyle.

24

Regardless of their reasons, to some extent,

all working learners share the common

experience of simultaneously navigating

enrollment in postsecondary education

and formal engagement in the labor market.

23 Rising tuition and other educational costs relative to family income and the rise in unmet financial need explain the proliferation

of working learners. Students are motivated to work in order to pay tuition costs when they receive federal aid in the form of

work-study or when the student and his/her family are unable or unwilling to pay the difference between college costs and

unmet financial need. For example, during the 1960s and 1970s, student employment rates grew consistently while family

income and public subsidies for college were growing faster than college costs (Stern and Nakata, Paid Employment Among U.S.

College Students, 1991). The “rising cost of college” thesis also does not account for the fact that employment among part-time

students has held steady since at least the 1970s while postsecondary education costs have experienced extraordinary growth.

Moreover, the simple explanation that students work to pay for college doesn’t account for the complexity of student financing

strategies, and the differences among student strategies regarding how they combine borrowing, working, and enrollment. For

example, students at two-year institutions are more likely to work without borrowing to pay for their education, and students

who enroll full-time are more likely to borrow (Cuccaro-Alamin and Choy, Postsecondary Financing Strategies, 1998). However,

working is a strategy that students pursue regardless of whether they receive financial aid without having to borrow, or receive

aid and still choose to borrow; while intensity of work is less for those who receive aid and do not borrow and the least for those

who receive aid and do borrow, wherein, nearly one in five students (19%) who receive aid and borrow still work full-time

(Horn and Berktold, Profile of Undergraduates in U.S. Postsecondary Education Institutions, 1998).

24 This perspective is somewhat supported by the fact that over 70 percent of dependent students from families with incomes

over $90,000 per year work, and about a third of these students worked more than 20 hours per week (King, Working Their Way

Through College, 2006). Perna et al. argue that older undergraduates grow as a share of total enrollment; they posit that these older,

financially independent students are more likely to work because they are already working adults with financial responsibilities. This

would include the subset of students for whom the question is not “Why work?” but “Why enroll in school?”

In order to better understand and compare the diverse experiences of

working learners, we have separated them into two groups based on age.

Young working learners are those aged 16-29; we refer to working learners

aged 30-54 as mature working learners.

25

The decision to divide working

learners into two age groups is for the purpose of clarity; making age 30 the

dividing line is somewhat arbitrary. We use age 30 because at that point,

most adults (including working learners) will be more established in the labor

market and in adulthood.

26

We also studied the income levels of working learners. We categorize those

whose annual earnings place them at 200 percent of the poverty line

27

and below as “low-income working learners.” The choices that this group

makes – including selection of undergraduate majors and selection of future

occupations, along with associated labor market outcomes – are important in

assessing the extent to which education has been an important tool for

lifting these and similarly disadvantaged groups out of poverty.

Young working learners (16-29) make very different decisions

compared to mature working learners (30-54) when it comes

to majors selected, hours worked, and career choices

Fourteen million Americans work while enrolled in a higher education

institution.

28

Two-thirds of working learners are between the ages of

16 and 29 (Figure 1).

25 Where the data support it, we include data on working learners between the ages of 16-18; for some data sets,

this is not possible due to data limitations. In these cases, young working learners are those aged 18-29.

26 This analysis of working learners uses five different data sources (more details in Appendix 1). The differing data sources allowed

more detailed analysis of the characteristics of working learners. However, it is important to note that the populations covered

are different in each of these databases.

27 The federal poverty threshold changes each year and is determined by family size. Two hundred percent of the poverty level

multiplies the federal poverty level by two ($23,540 for a single individual is 200% of the 2015 poverty level).

28 Includes both postsecondary institutions and graduate schools.

Who Are Working Learners?

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 25

Figure 1. The majority of working learners are between the

ages of 16 and 29.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of

U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

16-29

30-54

33%

67%

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

Figure 2. More than half of working learners are in sales and food/personal services occupations.

Sales and office support

Food and personal services

Blue collar

Education

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Managerial and professional office

Healthcare professional and technical

Healthcare support

Community services and arts

STEM

Sixty percent of working learners work in one of two career elds: sales and

oce support occupations (34%) and food and personal services occupations

(26%) (Figure 2). Many of these jobs are either temporary or part-time.

Many working learners leave these jobs after graduating, while others

move into higher paying jobs.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

26

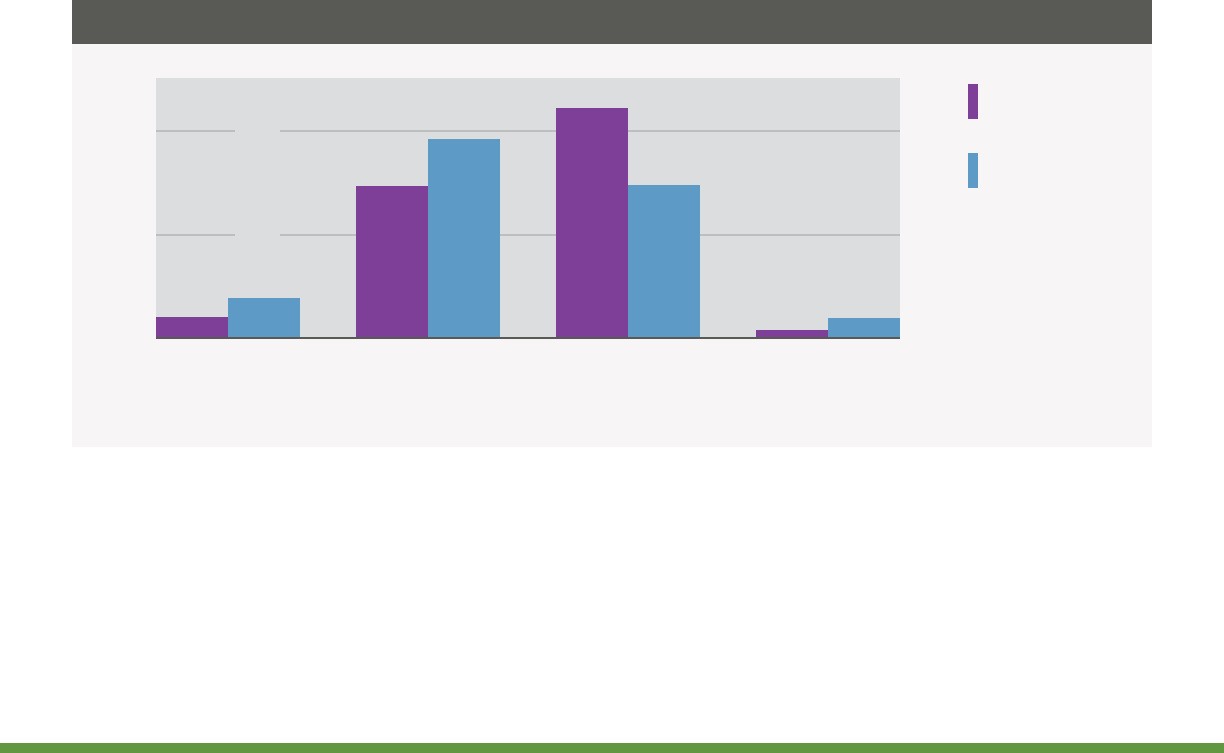

The distribution of jobs held by working

learners varies by age (Figure 3). While more

than a quarter of working learners between

the ages of 16 and 29 are employed in food and

personal service occupations – such as tending

bar, supersizing meals, and sweeping hair

clippings – the percentage of working learners

in those occupations drops to just 12 percent

for mature working learners. Working learners

transition from food and personal service

jobs into managerial positions as they gain

experience and credentials.

The majority (51%) of mature working learners

are employed in one of three career elds:

managerial occupations, education occupations,

and sales and oce support occupations.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis

of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

Figure 3. Young working learners are more likely to be in sales and office and food

and personal services occupations. Mature working learners are more concentrated in

management.

Sales and office support

Managerial and professional office

Blue collar

Education

Food and personal services

Healthcare professional and technical

Healthcare support

Community services and arts

STEM

Young working

learners (16-29)

34%

20%

17%

14%

12%

6%

8%

26%

Mature working

learners (30-54)

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 27

Working learners are more likely to hold jobs that are not related to their long-term career goals

– perhaps waiting tables or doing administrative work in an oce – but are more likely than other

workers to have long-term career goals (Figure 4).

Nearly 60 percent of working learners are women.

More women than men are enrolled in postsecondary institutions overall, and this is also true for

working learners. Indeed, women are more likely than men by a ratio of about 60:40 to be working

learners among the young and mature (Figure 5).

Figure 4. Working learners are more likely to be working in

transitional jobs not related to their long-term career goals.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data

from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health wave 4, 2008-2009.

Part of long-term career goals

Preparation for long-term career goals

Not related to long-term career goals

Do not have long-term career goals

Working only Working learners

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

28

Young working learners are disproportionately white, while mature working

learners are disproportionately African-American.

By race and ethnicity, the distribution of young

working learners reects that of the national

population. However, as workers age, the share

of working learners that is non-white rises –

attributable almost entirely to a larger share of

African-American working learners.

Within racial and ethnic categories, whites

comprise the majority of young and mature

working learners (62% and 57%, respectively,

compared with 64% for the general population),

but the share of African-American working

learners nearly doubles among mature

working learners (African-Americans are

12% of young working learners and about

23% of mature working learners).

29

Hispanic

young working learners are about 16 percent

of the working learner population, equal to

their share in the general population; this

drops to approximately 13 percent among

mature working learners. A similar pattern

holds for Asians.

Figure 5. Women are more likely to be working learners.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis

of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

Men

Women

Young working learners Mature working learners

41%59%

44%56%

29 As illustrated in Figure 6, African Americans represent 12 percent of the total population.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 29

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of

data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Review, 2012 and U.S. Census, 2010.

Figure 6. The majority of working learners are white, but mature

working learners are disproportionately African-American.

Young working learner

Mature working learner

U.S. Census data average

50%

25%

75%

White Black or African-

American

Hispanic

or Latino

Asian American Indian

or Alaska Native

Native Hawaiian/

other Pacific

Islander

Other/more

than one race

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

30

50%

25%

Mature working learners are more likely to be married with family responsibilities.

Stark dierences in family status characterize

young working learners and mature working

learners – mature working learners are much

more likely to be married and have children

than their young working learner counterparts

(Figure 7). Perhaps unsurprisingly, most young

working learners (60%) are single and do not

have dependents, compared with less than a

quarter of mature working learners. Young

working learners are also less likely to be

single parents; about 20 percent of young

working learners have at least one dependent,

but only 4 percent are unmarried; a larger

share of mature working learners have

dependents (about 60%), but about 17

percent are unmarried.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

analysis of data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study, 2012.

Figure 7. Mature working learners are more likely to be married than young working learners

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

Unmarried, no

dependent children

Unmarried with dependent

children

Married, no

dependent children

Married with

dependent children

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 31

Young working learners and mature working

learners are generally found in dierent types of

postsecondary institutions, and each group tends

to enroll in dierent types of degree-granting

programs. This is likely because mature working

learners have greater constraints on their time

(as they are more likely to be married and have

dependents, as well as to work longer hours).

As a result, mature working learners are more

prevalent in shorter-duration programs (i.e.,

those that are two years or less) such as those

that provide certicates and Associate’s degrees.

Likewise, mature working learners are more

likely than young working learners to be enrolled

in a postsecondary program that does not

provide a credential or degree upon completion.

These types of programs are often professional

in nature and oer a certicate of completion

based on attendance and not necessarily

completion of a formal examination. Young

working learners, by contrast, are most likely

to enroll in Bachelor’s degree programs oered

by selective, doctorate-granting institutions.

Fifty-six percent of young working learners are

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Review, 2012.

Figure 8. Young working learners are more likely to be enrolled in Bachelor’s degree programs.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

50%

Certificate Associate’s degree Bachelor’s degree Not in a degree program

or others

25%

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

32

in baccalaureate programs, compared with 37

percent of mature working learners, whereas 58

percent of mature working learners are enrolled

in AA or certicate programs, compared with

42 percent of young working learners (Figure

8). Among those enrolled in Associate’s degree

programs, young working learners are also

slightly more likely to be on an academic/

transfer, or general education track, whereas

mature working learners are more likely to be

in a technical or occupational Associate’s degree

program (33% of mature working learners are

in an occupational track, compared with 26%

of young working learners).

Mature working learners are concentrated in open-admission

community colleges and for-profit colleges and universities while

young working learners tend to go to more selective institutions.

The type of institution working learners attend

also varies by age. Almost half (46%) of young

working learners attend two-year public colleges,

and another 40 percent are enrolled in public

and private, not-for-prot, four-year institutions.

About 10 percent attend for-prot institutions.

By contrast, mature working learners attend

two-year public institutions (63%) and for-prot

institutions (20%) in greater numbers (Figure 9).

Even among working learners pursuing the

same degree, the institution type varies. For

example, among those enrolled in Bachelor’s

degree programs, mature working learners

are nine times more likely to be at for-prot

institutions compared with their young working

learner counterparts (18% of Bachelor’s degree-

seeking mature working learners are enrolled

in for-prot institutions, compared with only

2% of young working learners). By contrast,

roughly half (49%) of young working learners

are in public, four-year doctorate-granting

institutions, compared with just over a quarter

(28%) of mature-working learners.

30

Young working learners tend to go to more

selective institutions. For example, while equal

numbers (17%) of both young working learners

and mature working learners enroll in public,

four-year non-doctorate-granting institutions,

17 percent of young working learners enroll

in private, not-for-prot four-year doctorate-

granting institutions, compared to only 13

percent of mature working learners who enroll

in such institutions. Not only are young working

learners more likely to attend public two-year

and four-year institutions than mature working

learners, but such institutions are most likely

to be categorized as being either very selective

or moderately selective. In fact, more than

half of all young working learners attend

such institutions. Conversely, nine out of 10

mature working learners attend the least

selective institutions.

30 U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics, Baccalaureate & Beyond Longitudinal Study, 2008-12.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 33

Young working learners are more likely to select humanities and social sciences

majors while mature working learners select healthcare and business.

Young working learners are also more likely

than mature working learners to be liberal

arts majors, in programs such as visual and

performing arts, humanities, personal and

consumer services, education, communications,

English, history, and psychology (Figure 10).

Nearly half (49%) of mature working learners are

in either healthcare or business-related majors.

Mature working learners are also more likely

than their young working learner counterparts to

select majors for which the knowledge and skills

gained upon completion of the program of study

may be applied directly to a future career such as

military technology and protective service, public

administration, and law/legal studies programs.

Majors selected by young working learners are

less likely to be related to their occupations.

31

At the Associate’s degree level, young working

learners are more likely to be enrolled in general

education or transfer programs than their

mature working learner counterparts (74% vs.

68%), who are more likely to be enrolled in

technical programs (33% vs. 26%).

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Survey, 2003-2009.

Figure 9. Mature working learners are concentrated in two-year and for-profit institutions.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

Public or private

not-for-profit

4-year

50%

75%

25%

Public 2-year Public

less-than-2-year

Private not-for-

profit 2-year

For-profit

(2-year or 4-year)

31 An exception to this general finding applies to young working learners employed in the following technical or specialized fields:

artists and designers, sports occupations, and social service occupations.

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

34

Share of working learners

Computer and

information sciences

Engineering and

engineering technology

Biological and phys science,

sci tech, math, agriculture

General studies

and other

Healthcare fields

Education

Other Applied

Business

Social Sciences

Humanities

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce

analysis of data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study, 2012.

Figure 10. Business is the most popular major for both young and mature

working learners enrolled in Bachelor’s degree programs.

20%

Young working

learner

Mature working learner

Workforce outcomes dier for young and mature working learners due to:

• Dierent levels of labor market experience;

• Diering social and familial responsibilities, including dependency status by age; and

• Their self-identication as either “primarily students” or “primarily employees who

enroll in postsecondary programs.”

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 35

Mature working learners are more likely to be working full-time, but over a third

of young working learners work more than 30 hours per week while enrolled.

The mature working learner population divides

roughly evenly into those who are enrolled

full-time in a postsecondary program and those

who are enrolled part-time. Two-thirds of

young working learners attend postsecondary

institutions full-time.

Logically, with their heavier school

responsibilities, young working learners are

more likely to be employed part-time. Sixty-

three percent of young working learners work

fewer than 30 hours per week, and half of

those work fewer than 20 hours per week. The

number of hours worked varies signicantly

based on the level of education pursued, which

is likely also a function of both age

and dependency status (e.g., transitioning

from dependent to independent). Eighty-ve

percent of young working learners who

are classied as “dependents” are

employed part-time.

Mature working learners are most likely to work

at least 40 hours per week while enrolled. A

quarter of mature working learners work part-

time while enrolled. These patterns hold true

regardless of whether student loans are a factor.

Fifty-seven percent of young working learners

work 35 hours or fewer each week while

enrolled in school.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of

data from the Beginning Postsecondary Students Longitudinal Survey, 2003-2009.

Figure 11. Mature working learners tend to work longer hours while enrolled.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

1 - 19 20-29 30-39 40 or more

50%

75%

25%

Hours worked per week

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

36

Figure 12. Mature working learners work longer hours, regardless of

whether they are enrolled in undergraduate or graduate degree programs.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

Over 30 hours/week

21-30 hours/week

11-20 hours/week

0-10 hours/week

College

undergraduate

program

Young working learner Mature working learner

College graduate

professional

program

College

undergraduate

program

College graduate

professional

program

While they are enrolled, mature working learners work more hours than young working learners.

After they graduate, however, young and mature working learners work similar hours (Figure 12).

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 37

Working learners with a Bachelor’s degree tend

to work in similar occupations, regardless of

age or experience. Both young working learners

and mature working learners who have attained

Bachelor’s degrees are employed most frequently

in managerial and professional occupations

(22% for both groups); sales and oce support

occupations; education, training, and library

occupations; and STEM occupations. As

previously noted, mature working learners are

more likely to become employed in occupations

that are similar to their eld of study.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study, 2012.

Figure 13. After completion of a Bachelor’s degree, young and mature working learners work similar hours.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

1-19 20-29 30-39 40-49 50 or more

50%

25%

Hours worked per week

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

38

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey data, 2012-2013.

Figure 14. Working learners who have earned a Bachelor’s degree work in similar occupations.

Managerial and

professional office

Blue collar

Food and personal

services

Sales and office support

Healthcare professional

and technical

Education, training,

and library

Healthcare support

Social sciences

Community

services and arts

STEM

Young working learners Mature working learners

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 39

Mature working learners earn more than young working learners while enrolled.

While enrolled in a postsecondary program,

nancially independent young working learners

earn less than mature working learners. Nearly

70 percent of independent young working

learners earn less than $20,000 annually

(compared with only roughly 30% of mature

working learners). This disparity is likely a

reection of both the total number of hours

worked per week, the value of accumulated and

reinforced workforce experience, and the greater

likelihood of mature working learners working in

a professional eld.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Postsecondary Student Aid Review, 2012.

Figure 15. While enrolled, mature working learners earn more than young working learners.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

Less than $7,499 $7,500-$19,999 $20,000-$41,999 $42,000 or more

50%

25%

Learning While Earning: The New Normal

40

More than half of young working learners (52%) earn less than $43,000 annually, with 42 percent

earning between $20,000 and $42,999. Comparatively, only 38 percent of mature working learners

earn less than $43,000, with 30 percent earning between $20,000 and $42,999. At the higher end

of the income spectrum, about 40 percent of mature working learners earn more than $60,000 per

year, compared with 23 percent of young working learners (Figure 16).

Mature working learners are the most likely to earn comparatively higher salaries. More than 75

percent of young working learners earn less than $60,000 annually, whereas only 60 percent of

mature working learners, holding the same postsecondary degree, earn less than $60,000 annually.

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the Baccalaureate and Beyond Longitudinal Study, 2012.

Figure 16. After completing a Bachelor’s degree, mature working learners are more likely to earn high incomes.

Young working

learner

Mature working

learner

$1-$20,899 $20,900-$42,999 $43,000-$59,999 $60,000+

40%

20%

Learning While Earning: The New Normal 41

Source: Georgetown University Center on Education and the Workforce analysis of data from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent to Adult Health

wave 4, 2001-2009.

Figure 17. Working learners are more likely to have attended college

or gotten a degree than full-time students or full-time workers.

Some college or an

Associate’s degree

Bachelor’s degree

Graduate degree

High school or less

Working learner Student only Working only