2022 Fireworks Annual Report

Fireworks-Related Deaths, Emergency Department-

Treated Injuries, and Enforcement Activities During

2022

June 2023

Blake Smith

Division of Hazard Analysis

Directorate for Epidemiology

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission

Dustin Pledger

Office of Compliance and Field Operations

U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission

This report was prepared by the CPSC staff.

It has not been reviewed or approved by,

and may not necessarily reflect the views of,

the Commission.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

2

Executive Summary

This report provides the results of U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC)

staff’s analysis of data on non-occupational, fireworks-related deaths and injuries during

calendar year 2022. The report also summarizes CPSC staff’s enforcement activities during

fiscal year 2022.

1

Staff obtained information on fireworks-related deaths from news clippings and other

sources in CPSC’s Consumer Product Safety Risk Management System (CPSRMS). Staff also

estimated fireworks-related injuries treated in hospital emergency departments from CPSC’s

National Electronic Injury Surveillance System (NEISS). Finally, CPSC staff conducted a special

study of non-occupational, fireworks-related injuries between June 17, 2022, and July 17, 2022.

The special study included collecting and analyzing more detailed incident information, such as

the type of injury, the fireworks involved, the characteristics of the victim, and the incident

scenario. About 73 percent of the estimated annual fireworks-related, emergency department-

treated injuries for 2022 occurred during that period.

Highlights of the report

Deaths and Injuries

• CPSC staff received reports of 11 non-occupational, fireworks-related deaths during

2022. Five of the deaths were associated with firework misuse; three deaths were

associated with a device misfire/malfunction; one death was associated with a device

tip-over; and two incidents were associated with unknown circumstances. Reporting of

fireworks-related deaths for 2022 is not complete, and the number of deaths identified

for 2022 should be considered a minimum.

• Fireworks were involved with an estimated 10,200 injuries treated in U.S. hospital

emergency departments during calendar year 2022 (95 percent confidence interval

7,800–12,500). The estimated rate of emergency department-treated injuries is 3.1 per

100,000 individuals in the United States, a decrease from 3.5 estimated injuries per

100,000 individuals in 2021.

• There is a statistically significant trend in estimated emergency department-treated,

fireworks-related injuries from 2007 through 2022. This trend estimates an increase of

535 fireworks injuries per year (p-value = <0.0001).

• In 2022, there were proportionately fewer white victims (5,100 total injuries, 69.9% of

victims, 75.6% of the U.S. population identifies as white), proportionately more black

victims (1,500 total injuries, 20.5% of victims, 13.6% of the U.S. population identifies as

black), and proportionately fewer victims associated with some other race (700 total

1

The 2022 federal fiscal year refers to the period of October 1, 2021, through September 30, 2022.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

3

injuries, 9.6% of victims, 10.8% of the U.S. population identifies with some other race).

2

There were 2,800 fireworks-related injuries where the race of the victim was unknown.

These percentages are calculated using only the victims where race was collected.

• In 2022, there were proportionately fewer injuries where the victim identified as Hispanic

(800 total injuries,11.1% of victims, 19.1% of the U.S population identifies as Hispanic)

and proportionately more injuries where the victim identified as non-Hispanic (6,400 total

injuries, 88.9% of victims, 80.9% of the U.S population identifies as non-Hispanic). There

were 3,000 fireworks-related injuries where the ethnicity of the victim was unknown.

These percentages are calculated using only the victims where ethnicity was collected.

• An estimated 7,400 fireworks-related injuries (or 73 percent of the total estimated

fireworks-related injuries in 2022) were treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments

during the 1-month special study period between June 17, 2022, and July 17, 2022 (95

percent confidence interval 5,300–9,600).

Results from the 2022 Special Study

• Of the 7,400 estimated fireworks-related injuries sustained, 65 percent were to males

and 35 percent were to females.

• Adults 25 to 44 years of age experienced about 36 percent of the estimated injuries, and

children younger than 15 years of age accounted for 28 percent of the estimated injuries.

Seniors 65+ years of age experienced a small percent of the estimated injuries at only 3

percent.

• Victims 15 to 19 years of age had the highest estimated rate of emergency department-

treated, fireworks-related injuries (6.0 injuries per 100,000 people). Children, 10 to 14

years of age, had the second highest estimated rate (3.7 injuries per 100,000 people). A

general decrease is noted comparing the 2022 rates to the 2021 rates, except for victims

15 to 24 years of age, which saw an increase from 4.0 injuries to 4.2 injuries per 100,000

people.

• There were an estimated 1,300 emergency department-treated injuries associated with

firecrackers and 600 with sparklers.

• The parts of the body most often injured were hands and fingers (an estimated 29

percent); head, face, and ears (an estimated 19 percent); legs (an estimated 19

2

The “other” race category contains Asian, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, and American Indian/Alaskan Native

individuals with more than one race.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

4

percent); eyes (an estimated 16 percent); trunk/other regions (an estimated 12 percent);

and arms (an estimated 5 percent).

• An estimated 38 percent of the emergency department-treated injuries were burns.

Burns were the most common injury to hands and fingers. Contusions and lacerations,

accounting for 30 percent of the emergency department-treated injuries, were the most

common injury to the head, face, and ears.

• Approximately 88 percent of the victims were treated at the hospital emergency

department and then released. An estimated 11 percent of patients were treated and

transferred to another hospital, or they were admitted to the hospital.

• CPSC staff conducted telephone follow-up investigations on a selected sample of

fireworks-related injuries reported in NEISS during the special study period, to clarify

information about the incident scenario or fireworks type. A review of data from the 10 in-

scope completed follow-up investigations showed that most injuries were associated

with misuse or malfunction of fireworks. Most victims recovered or were expected to

recover completely. However, there was one victim who reported that their injuries might

be long-term.

Enforcement Activities

During fiscal year 2022, CPSC’s Office of Compliance and Field Operations continued to

work closely with other federal agencies to conduct surveillance on consumer fireworks and to

enforce the provisions of the Federal Hazardous Substances Act.

Approximately 43% percent of the selected and tested products were found to contain

noncompliant fireworks. These noncompliant fireworks devices had a combined estimated

import value of $443,000. The violations consisted of fuse violations, presence of prohibited

chemicals, burnout or blowout, and pyrotechnic materials overload. Compared to previous

years, the percentage of tested products determined to be violative was significantly higher;

CPSC will closely monitor fireworks-related violations to determine if the rate of noncompliance

during fiscal year 2022 was anomalous.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

5

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ................................................................................................................. 2

Highlights of the report ........................................................................................................... 2

Deaths and Injuries ............................................................................................................. 2

Results from the 2022 Special Study .................................................................................. 3

Enforcement Activities......................................................................................................... 4

1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 7

Sources of Information ........................................................................................................... 7

Statistical methods ................................................................................................................. 9

2. Fireworks-Related Deaths for 2022 ....................................................................................10

3. National Injury Estimates for 2022 .....................................................................................13

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries: 2007-2022 .............14

Figure 1: Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries: 2007-2022

..............................................................................................................................................15

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Race: 2007-2022

..............................................................................................................................................17

Figure 2: Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Race:

2007-2022 .............................................................................................................................18

4. Injury Estimates for the 2022 Special Study: Detailed Analysis of Injury Patterns ........18

Fireworks Device Types and Estimated Injuries ....................................................................18

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Device Type: June

17–July 17, 2022 ...................................................................................................................19

Gender and Age of Injured Persons ......................................................................................20

Figure 3: Estimated Injuries by Gender: June 17 – July 17, 2022 ..........................................20

Figure 4: Percentage of Injuries by Age Group: June 17 – July 17, 2022 ...............................21

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Age and Gender:

June 17–July 17, 2022 ..........................................................................................................22

Age and Gender of the Injured Persons by Type of Fireworks Device ...................................23

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Device Type and

Age Group: June 17–July 17, 2022 .......................................................................................24

Body Region Injured and Injury Diagnosis .............................................................................25

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

6

Figure 5: Body Regions Injured: June 17 – July 17, 2022 ......................................................25

Figure 6: Types of Injuries: June 17 – July 17, 2022 ..............................................................26

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Body Region and

Diagnosis: June 17–July 17, 2022 .........................................................................................27

Types of Fireworks Devices and Body Regions Injured .........................................................28

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Type of Fireworks

Device and Body Region Injured: June 17–July 17, 2022 ......................................................28

Hospital Treatment ................................................................................................................29

5. Telephone Investigations of Fireworks-Related Injuries ..................................................29

Final Status of Telephone Investigations ...............................................................................30

Summary Statistics ................................................................................................................30

Hazard Patterns ....................................................................................................................31

Hazard Patterns as Described in Telephone Investigations for Fireworks-Related Injuries ....31

Long Term Consequences of Fireworks-Related Injuries ......................................................34

Where Fireworks Were Obtained ...........................................................................................34

6. Enforcement Activities .......................................................................................................35

7. Summary .............................................................................................................................35

References ..............................................................................................................................37

Appendix A ..............................................................................................................................38

Fireworks-Related Injuries and Imported Fireworks ...............................................................38

Estimated Fireworks-Related Injuries and Estimated Fireworks Imported into the United

States by Weight: 2007-2022 ................................................................................................39

Appendix B ..............................................................................................................................40

Telephone Investigations .......................................................................................................40

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

7

1. Introduction

This report describes injuries and deaths during calendar year 2022 associated with

fireworks devices, as well as kits and components used to manufacture illegal fireworks.

Reports for earlier years in this series can be found at:

https://cpsc.

gov/Research--Statistics/Fuel-

Lighters-and-Fireworks1.

This report is organized into seven sections. Section 1 describes the data and statistical

methods used in this analysis. Section 2 summarizes the 2022 fireworks-related incidents that

resulted in deaths. Section 3 provides an annual estimate of fireworks-related, emergency

department-treated injuries in the United States for 2022, and it compares that estimate to

previous years. Section 4 analyzes emergency department-treated, fireworks-related injuries

during the month around July 4, 2022. Section 5 summarizes the telephone in-depth

investigations of a subsample of the injury incidents that occurred during that period. Section 6

describes enforcement activities of CPSC’s Office of Compliance and Field Operations (EXC)

during fiscal year 2022. The report concludes with a summary of the findings in Section 7.

Appendix A is a table depicting the relationship between fireworks-related injuries and fireworks

imports between 2007 and 2022. Appendix B provides details on the completed telephone

investigations.

Sources of Information

Staff obtained information on non-occupational, fireworks-related deaths during 2022

from CPSC’s CPSRMS. CPSRMS combines data from CPSC’s Injury or Potential Injury

Incident File (IPII), Death Certificate File (DTHS), and In-Depth Investigation File (INDP) into

one incident database. Entries in IPII come from a variety of sources, such as newspaper

articles, consumer complaints, lawyer referrals, medical examiners, and other government

agencies. CPSC staff from the Office of Compliance and Field Operations conducted in-depth

investigations of the deaths to determine the types of fireworks involved in the incidents and the

circumstances that led to the fatal injuries.

Because the data in IPII are based on voluntary reports, and because it can take more

than 2 years to receive all the death certificates from the various states to complete the DTHS,

neither data source can be considered complete for 2021 or 2022 fireworks-related deaths at

the time this report was prepared. Consequently, the number of deaths should be considered a

minimum. Staff updates the total number of deaths for previous years when new reports are

received. Total deaths for prior years may not coincide with the number in reports for earlier

years because of these updates.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

8

The source of information on non-occupational, emergency department-treated

fireworks-related injuries is CPSC’s NEISS. NEISS is a probability sample of the U.S. hospitals

with emergency departments.

3

Injury information is taken from the emergency department

record. This information includes the victim’s age and sex, the place where the injury occurred,

the emergency department diagnosis, the body part injured, and the consumer product(s)

associated with the injury. The information is supplemented by a narrative of 140 to 400

characters

4

in length and that often contains a brief description of how the injury occurred.

To supplement the information available in the NEISS record, CPSC staff conducts a

special study of fireworks-related injuries every year during the month around July 4. Staff focus

their efforts on fireworks incidents during this period because, in most years, about two-thirds to

three-quarters of the annual injuries occur then. During this period, hospital emergency-

department staff shows patients pictures of several types of fireworks to help them identify the

type of fireworks device associated with their injuries. The type of fireworks involved in the

incident are then included in the NEISS narrative. In 2022, the special study period lasted from

June 17 to July 17.

After reading the incident case records, including the narrative descriptions of the

fireworks device and the incident scenario, CPSC staff may assign a case for additional

telephone investigation. Staff usually selects cases that involve the most serious injuries and/or

hospital admissions. Serious injuries include eye injuries, finger and hand amputations, and

head injuries. Cases also may be assigned to obtain more information about the incident than

what is reported in the NEISS narrative. In most years, phone interviewers can collect

information for one-fifth to one-half of the cases assigned. Information on the final status of the

telephone interviews conducted during the 2022 special study is in Section 5 and Appendix B of

this report.

In the telephone investigations, information is requested directly from the victim (or the

victim’s parent, if the victim is a minor) about the type of fireworks involved, where the fireworks

were obtained, how the injury occurred, and the medical treatment and prognosis. When the

fireworks device reported in the telephone investigation is different from what is reported in the

NEISS emergency department record, the device reported in the telephone investigation is used

in the data for this report.

As a result of this investigative process, three distinct levels of information may be

available about a fireworks-related injury case. For cases that occur before or after the July 4

special study period, the NEISS record is almost always the only source of information. Many

3

For a description of NEISS, including the revised sampling frame, see Schroeder and Ault (2001). Procedures used

for variance and confidence interval calculations and adjustments for the sampling frame change that occurred in

1997 are found in Marker, Lo, Brick, and Davis (1999). SAS® statistical software for trend and confidence interval

estimation is documented in Schroeder (2000). SAS® is a product of the SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC. Lo, Brick, and

Davis (1999). SAS® statistical software for trend and confidence interval estimation is documented in Schroeder

(2000). SAS® is a product of the SAS Institute, Inc. Cary, NC.

4

The maximum available number of characters changed from 142 to 400 characters on January 1, 2019.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

9

NEISS records collected outside the special study period do not specify the type of fireworks

involved in the incident. Additional information is typically available during the special study

period because the NEISS records collected by the emergency departments usually contain the

type of fireworks and additional details on the incident scenario. Finally, the most information is

available for the subset of the special study cases where staff conducted telephone

investigations. These various levels of information about injuries correspond to these different

analyses in the report:

• Estimated national number of fireworks-related, emergency department-treated injuries.

This estimate is made using NEISS cases for the entire year, from records where

fireworks were specified as one of the consumer products involved. For cases outside the

special study period, as noted above, there is usually no information on the fireworks type, and

limited information is available on the incident scenario. Consequently, there is not enough

information to determine the role played by the fireworks in the incident. Thus, the annual injury

estimate may include a small number of cases in which the fireworks device was not lit, or no

attempt was made to light the device. Calculating the annual estimates without removing these

cases makes the estimates comparable to previous years.

• Detailed analyses of injury patterns

The tables are based on the special study period only, and they describe fireworks type,

body part injured, diagnosis, age and sex of injured people, and other relevant information.

Fireworks-type information is taken from the telephone investigation or the NEISS comment

field when there was no telephone investigation. When computing estimates for the special

study period, CPSC staff does not include cases in which the fireworks device was not lit, or no

attempt was made to light the device.

• Information from telephone investigations

Individual case injury descriptions and medical prognosis information from the telephone

investigations are provided in Appendix B. These summaries also exclude cases in which the

fireworks device was not lit, or no attempt was made to light the device. These cases represent

a sample of some of the most serious fireworks-related injuries and may not represent the

typical emergency department-treated, fireworks-related injuries.

Statistical methods

Injuries reported by hospitals in the NEISS sample were weighted by the NEISS

probability-based sampling weights to develop an estimate of total U.S. emergency department-

treated, fireworks-related injuries for the year and for the special study month around July 4.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

10

Confidence intervals were estimated, and other statistics were calculated using computer

programs that were written to take the sampling design into consideration.

5

Estimated injuries

are rounded to the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50 injuries are shown with an

asterisk (*). Percentages are calculated from the actual estimates. Percentages may not add to

subtotals or to the total in the tables or figures, due to rounding.

This report also contains several detailed tables about fireworks-related injuries during

the special study period. National estimates in these tables were also made using the sampling

weights. To avoid cluttering the tables, confidence intervals are not included. Because the

estimates are based on subsets of data, they have larger relative sampling errors (i.e., larger

coefficients of variation) than the annual injury estimate or the special study injury estimate.

Therefore, interpretation and comparison of these estimates with each other, or with estimates

from prior years, should be made with caution. For example, when comparing subsets of the

data–such as between injuries associated with two different types of fireworks, or between two

different age groups–it is difficult to determine how much of the difference between estimates is

associated with sampling variability and how much is attributed to real differences in national

injury totals.

2. Fireworks-Related Deaths for 2022

CPSC has reports of 11 non-occupational, fireworks-related deaths that occurred during

2022.

6

Reporting of fireworks-related deaths for 2022 is not complete, and the number of deaths

in 2022 should be considered a minimum. Brief descriptions of the incidents, using wording

taken from the incident reports, follow:

• In January, a 21-year-old male was fatally injured from a fireworks blast outside of his

home. The victim lit a mortar type firework when the device unexpectedly detonated

early. The victim was struck in the right shoulder and was killed instantly. Emergency

services were called and transported the victim to the hospital where the victim was

pronounced dead. The official cause of death was not determined as the case is still

under investigation.

• In January, a house explosion killed a 17-year-old male as well as one unidentified

person. The two decedents were found dead at the scene. The blast also injured several

others. The group of victims were utilizing explosives to create fireworks in the garage.

The local fire chief stated that the ATF found numerous boxes (of materials) that the

5

See Schroeder (2000).

6

CPSC staff excludes incidents that are indirectly fireworks related. For instance, fireworks that start fires and lead to

deaths are excluded based on the logic that the fire is solely responsible for the death.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

11

victims ordered online. A neighbor was nearby and described the scene as “pure chaos.”

The neighbor continued saying that she saw flames engulfing the home and a young boy

and others running frantically. Investigators with the regional bomb and arson squad

stated that the brick home’s garage was leveled and the home itself was a burned-out

shell with a partial wall standing.

• In February, a 28-year-old male was fatally injured by an illegal mortar-style firework

blast on a frozen lake. The victim was with friends celebrating the life of a friend who had

passed away a year earlier. Four males went onto the ice to light the fireworks, two men

stayed at a distance while the other two lit the fireworks. After the explosion, the victim

was seen lying on the ice not moving. His friends tended to the victim while waiting for

emergency services to arrive. The victim was pronounced deceased at the scene.

Emergency services stated that the victim had major injuries on the right side of his

upper torso extending from chest to the head. The official cause of death was “Traumatic

Injuries of Head, Neck, Chest, and Right Upper Extremity” and ruled accidental. The

victim’s friends admitted to consuming alcohol on the day of the event.

• In June, a 26-year-old male was fatally injured while shooting off rocket type fireworks on

the shore of a bay. The victim was celebrating a friend’s graduation when he

successfully shot a firework into the air. He then lit a second device which did not go off.

The victim examined the malfunctioning device when it detonated. The victim collapsed

immediately. One of the party goers picked up the victim, carried him to a car, and

administered first aid in the back seat while another drove to the emergency room. At the

hospital, another unexploded firework was found in the pocket of the victim’s pants. The

victim remained in critical condition for over three days before being removed from life

support and being pronounced dead.

• In July, an 11-year-old male was fatally injured while shooting off fireworks with a group

of adults. The victim was holding a lit mortar-type device above his head. The shell

exited the bottom of the mortar and entered the victim’s skull. The mother of the victim

was present during the incident and stated that she held her son’s broken skull and brain

in her hands. Emergency services arrived and were transporting the victim to a local

high school parking lot for air transport. The victim was pronounced deceased before the

air transport arrived. Detectives believe that the device was loaded correctly, and that

the device malfunctioned. The official cause of death is listed as “Open head injuries due

to fireworks mortar.”

• In July, a 43-year-old male was fatally injured when lighting off fireworks during a party.

Eyewitnesses of the event indicated that the victim was lighting a mortar-style device

when the tube tipped over and shot directly at the victim. A party attendee attempted

lifesaving efforts. Emergency responders transported the victim to a local hospital where

further lifesaving efforts were unsuccessful. The victim was pronounced dead with an

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

12

official cause of death of “Traumatic cardiac arrest due to explosive injuries to the head

and neck due to unsafe firework use.”

• In July, an 18-year-old male was fatally wounded when lighting of a mortar-style

fireworks device at a park. One of the victim’s friends had lit a couple of artillery style

fireworks while holding the tube in his hand with no incident. Witnesses stated that the

victim held the tube in both hands near his face and chest when the mortar exploded in

his hands. Following the explosion, the victim made a groaning noise and immediately

fell to the ground. The victim’s friends called emergency services and began performing

CPR. Emergency services arrived at the scene and transported the victim to the hospital

where he was pronounced deceased on arrival. The victim and friends were consuming

alcohol at the time of the event.

• In July, a 42-year-old male was killed while lighting a mortar-style firework device at a

celebration at a friend’s house. The victim was holding the launching tube in his hand

and lifted the lit device above his head when a huge explosion occurred. The victim fell

to the ground and was unconscious immediately. The victim sustained a large hole in the

side of his neck and body cavity. Nearby family members attempted to stop the bleeding

while waiting for emergency services to arrive. Emergency responders transported the

victim to the hospital where he was declared deceased on arrival. The arson chief

believes it is a possibility that the victim inadvertently loaded the mortar canister upside

down in the launch tube. The victim was consuming alcohol at the time of the event.

• In July, and 18-year-old male was fatally wounded after lighting a mortar style firework in

a park. Police reported that the victim was struck by the mortar which killed the victim

instantly. The medical examiner listed the official cause of death as “Multiple blast-

related injuries to the head and neck, decapitation, avulsion of brain, multiple calvarial

and basilar skull fractures, facial fractures, and cervical vertebrae fractures. Fractures of

maxilla and mandible, multiple lacerations of the tongue, cutaneous abrasions,

contusions, and lacerations. Injuries to the torso, bilateral rib fractures and fracture of the

sternum and cutaneous abrasions, contusions, and lacerations of extremities.” No other

information regarding the incident was provided.

• In July, a 42-year-old male was killed when lighting off fireworks in the street near his

home. Nearby witnesses claimed that the victim lit a mortar-style device and placed the

mortar tube on top of his own head. When the device detonated the victim instantly fell

to the ground. A witness checked on the victim and noticed that he had severe wounds

to his hands and head. When emergency personnel arrived at the scene the victim was

pronounced deceased. Alcohol was being consumed at the time of the incident.

• In July, a 41-year-old male was killed by a lit firework device which struck the victim in

the torso, causing severe abdominal injuries at his home. Emergency services were

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

13

contacted, and the victim was transported to the local hospital. Doctors pronounced the

victim deceased a brief time after his arrival.

Including the 11 deaths described above, CPSC staff has reports of 162 fireworks-related

deaths between 2007 and 2022, for an average of 10.1 deaths per year.

7

3. National Injury Estimates for 2022

Table 1 and Figure 1 present the estimated number of non-occupational, fireworks-

related injuries treated in U.S. hospital emergency departments between 2007 and 2022.

7

See previous reports in this series (e.g., the report for 2021: Smith, Marier and Timian (2022)). In the most recent

three years, the number of deaths included 20 deaths in 2019, 24 deaths in 2020, and 15 deaths in 2021. The data

from 2019 to 2021 have been updated based on new incident reports received by CPSC staff during 2022 and may

differ from previous reports.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

14

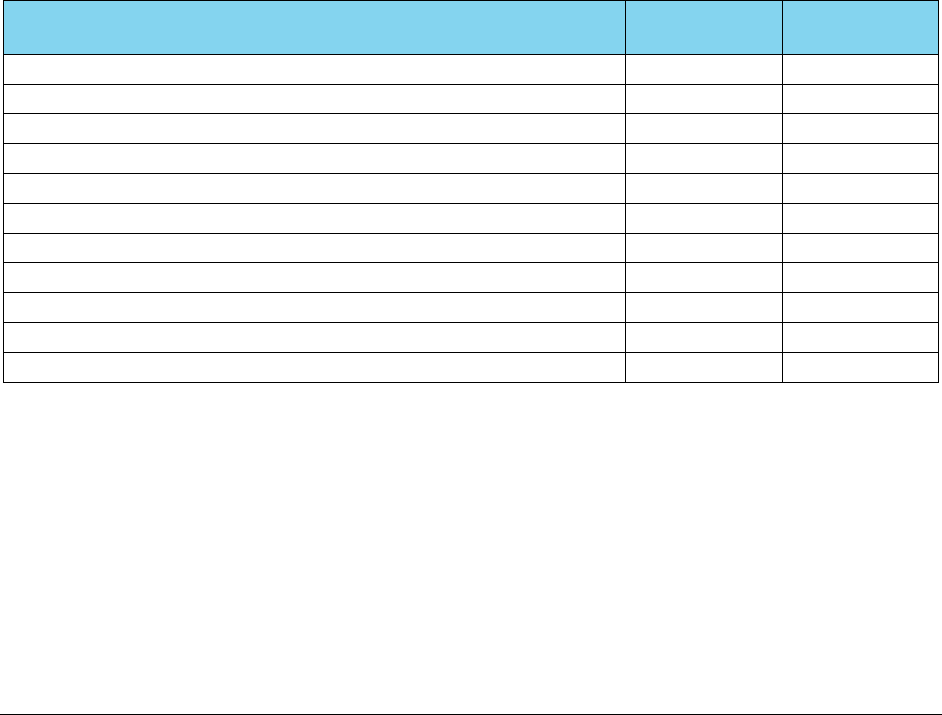

Table 1

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries: 2007-2022

Year

Estimated Injuries

Injuries per 100,00 People

2022 10,200 3.1

2021 11,500 3.5

2020

15,600

4.7

2019

10,000

3.0

2018

9,100

2.8

2017

12,900

4.0

2016

11,100

3.4

2015

11,900

3.7

2014

10,500

3.3

2013

11,400

3.6

2012

8,700

2.8

2011

9,600

3.1

2010

8,600

2.8

2009

8,800

2.9

2008

7,000

2.3

2007

9,800

3.3

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the

United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020, to July 1, 2022 (NST-EST2022-

POP). Population Estimates for 2010 to 2020 are from Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United

States, Regions, States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019; April 1, 2020; and

July 1, 2020 (NST-EST-2020). Population estimates for 2007 to 2009 are from Table 1. Annual Estimates of the

Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2009 (NST-

EST2009). Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau

There is a statistically significant increasing trend in the fireworks-related injury

estimates from 2007 through 2022 (p-value=<0.0001).

8

The slope of the fitted trend line shows

an increase of about 535 injuries per year. In calendar year 2022, there were an estimated

10,200 fireworks-related, emergency department-treated injuries (95 percent confidence interval

7,800 – 12,500). There were an estimated 11,500 such injuries in 2020. The difference between

the injury estimates for 2021 and 2022 is not statistically significant (p-value = 0.2871).

8

For details on the method to evaluate a trend that incorporates the sampling design, see Schroeder (2000) and

Marker et al. (1999).

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

15

Figure 1: Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries: 2007-

2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the

United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020, to July 1, 2022 (NST-EST2022-

POP). Population Estimates for 2010 to 2020 are from Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United

States, Regions, States, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2019; April 1, 2020; and

July 1, 2020 (NST-EST-2020). Population estimates for 2007 to 2009 are from Table 1. Annual Estimates of the

Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2000, to July 1, 2009 (NST-

EST2009). Population Division, U.S. Census Bureau

Appendix A contains a table showing estimated fireworks-related, emergency

department-treated injuries and fireworks imports between 2007 and 2022.

Table 2 shows that each year, the number of victims treated are mostly white, followed

by victims of an unknown race, Black victims, and victims of some other race. The “other” race

category contains Asian, Pacific Islander/Native Hawaiian, and American Indian/Alaskan Native

individuals and multiracial individuals. CPSC began collecting ethnicity information in 2018,

which includes information about whether a victim is Hispanic; as a result, ethnicity information

cannot be included at this time for the full 2007-2022 period. However, for 2022 alone, there

were 6,400 injuries where the victim did not identify as Hispanic (62.7% of total), 800 injuries

where the victim identified as Hispanic (7.8% of total), and 3,000 injuries where the victim’s

ethnicity was unknown (29.4% of total).

Figure 2 shows the trend by race across years; there is a statistically significant upward

trend for both white victims (p = 0.0019) as well as Black victims (p = 0.0132), but not for “other”

race victims (p = 0.9549). Between the years 2021 and 2022, there was no significant change in

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

0

2,000

4,000

6,000

8,000

10,000

12,000

14,000

16,000

18,000

Injury Rates

Estimated Injuries

Year

Fireworks Injuries Injuries per 100,000 People

Trend (Fireworks Injuries) Trend (Injuries per 100,000 People)

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

16

the number of white victims (p=0.5913) and neither Black nor “other” race victims experienced a

significant change.

When comparing the proportion of victims with a known race to the US population,

9

there were proportionately fewer white victims (69.9% of victims, 75.6% of the U.S. population

identifies as white), proportionately more black victims (20.5% of victims, 13.6% of the U.S.

population identifies as black), proportionately less victims associated with an “other” race (9.6%

of victims, 10.8% of the U.S. population identifies as another race).These percentages are

calculated using only the victims where race was collected. Victims with unknown race values

accounted for over 27.5% of all fireworks incidents in 2022.

9

Total U.S. Population race estimates obtained from Monthly Population Estimates for the United States: April 1,

2020 to December 1, 2023 (NA-EST2022-POP);

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

17

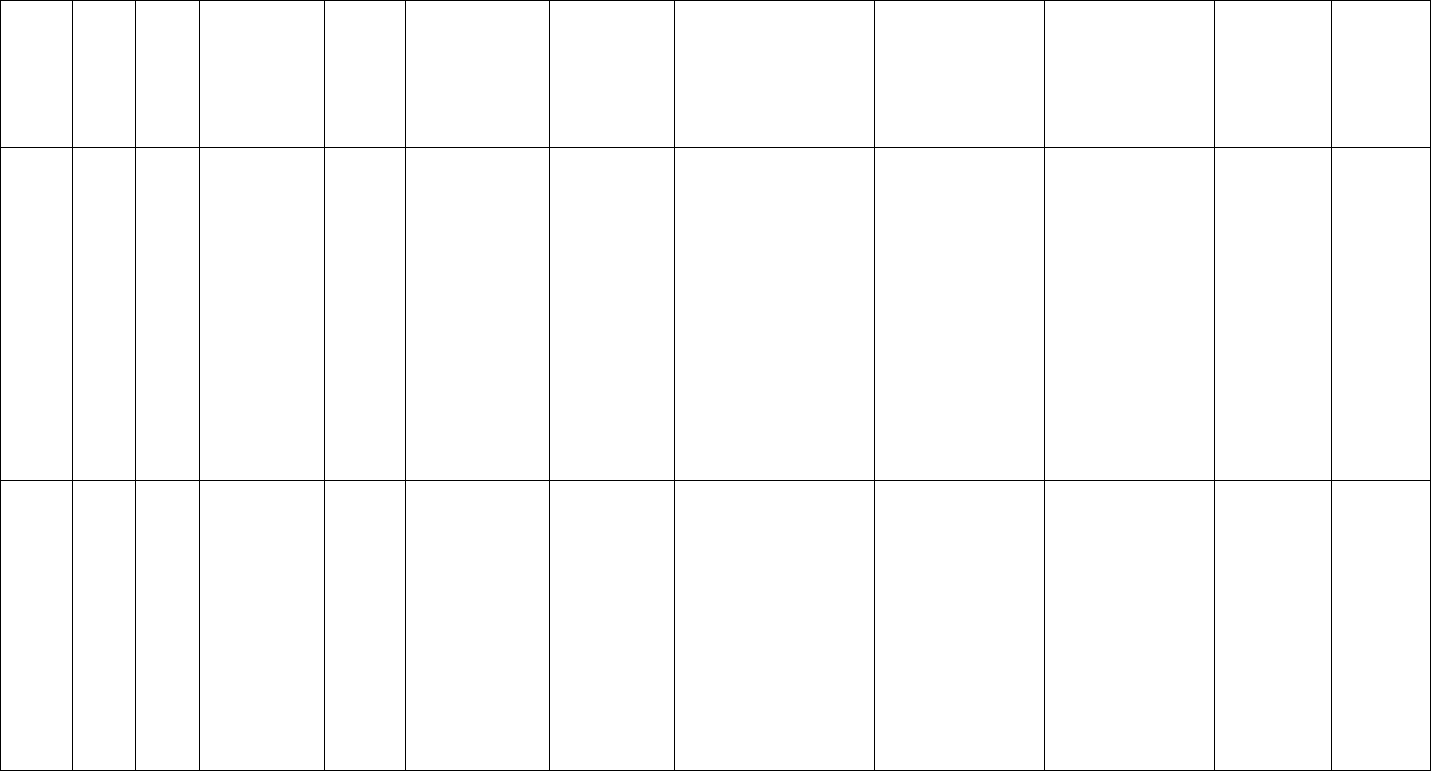

Table 2

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Race:

2007-2022

Year

White

Black/African

American

Other

Unknown

Total

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

%

N

2007

5,500

56.8

800

8.6

500

5.6

3,000

29.0

9,800

2008

4,500

63.8

400

6.4

400

5.9

1,700

23.9

7,000

2009

6,000

68.6

600

7.4

400

4.9

1,700

19.1

8,800

2010

5,000

58.4

600

7.1

600

6.6

2,400

27.9

8,500

2011

5,800

60.8

800

8.7

1,200

12.6

1,700

17.9

9,600

2012

5,200

59.6

800

8.8

700

10.0

1,900

21.6

8,700

2013

6,800

60.0

600

5.4

1,000

9.2

2,900

25.4

11,400

2014

5,600

52.9

800

7.8

600

5.5

3,600

33.8

10,500

2015

6,400

53.7

1,000

8.3

1,000

8.5

3,500

29.5

11,900

2016

5,800

51.9

1,500

13.3

1,400

12.4

2,500

22.4

11,100

2017

7,100

54.9

800

6.3

1,600

12.5

3,400

26.4

12,900

2018

4,900

53.7

1,200

12.7

700

8.0

2,400

25.7

9,000

2019

5,500

54.7

1,500

14.9

400

3.8

2,700

26.6

10,000

2020

8,100

51.5

3,000

18.7

1,000

6.7

3,600

23.1

15,600

2021

5,600

49.1

1,700

14.7

600

5.2

3,600

31.0

11,500

2022

5,100

50.0

1,500

14.7

700

6.9

2,800

27.5

10,200

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

Race percentages do not match the previous paragraph’s values, as incidents with unknown race values are included

in the calculations for Table 2.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

18

Figure 2: Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Race:

2007-2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission.

4. Injury Estimates for the 2022 Special Study:

Detailed Analysis of Injury Patterns

The injury analysis in this section presents the results of the 2022 special study of

fireworks-related injuries treated in hospital emergency departments between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. During this period, there were an estimated 7,400 fireworks-related injuries

(sample size=168, 95 percent confidence interval 5,300 – 9,600) accounting for 73 percent of

the total estimated fireworks-related injuries for the year, which is not statistically lower than the

estimated 8,500 fireworks-related injuries in the 2021 special study period (p-value = 0.3876).

The remainder of this section provides the estimated fireworks-related, emergency

department-treated injuries from this period, broken down by fireworks device type, victims’

demographics, injury diagnosis, and body parts injured.

Fireworks Device Types and Estimated Injuries

Table 3 shows the estimated number and percent of emergency department-treated

injuries by type of fireworks device during the special study period of June 17, 2022, to July 17,

2022.

0

1,000

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

6,000

7,000

8,000

9,000

2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Estimated Injuries

White Black/African-American

Other Trend (White)

Trend (Black/African-American) Trend (Other)

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

19

Table 3

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Device

Type: June 17–July 17, 2022

Fireworks Device Type

Estimated Injuries

Percent

Total

7,400

100%

All Firecrackers

1,300

18%

Small

200

2%

Illegal

500

6%

Unspecified

700

9%

All Rockets

400

6%

Other Rockets

300

5%

Bottle Rockets

100

1%

Other Devices

1,500

20%

Multiple Tube

100

1%

Reloadable

100

2%

Roman Candles

400

6%

Novelties

200

2%

Sparklers

600

8%

Helicopters

100

2%

Homemade/Altered

*

*

Public Display

100

2%

Unknown

4,100

55%

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on 168 NEISS emergency department-reported

injuries between June 17, 2022, and July 17, 2022, and supplemented by 10 completed In-Depth Investigations.

Firework types are obtained from the in-depth investigation, when available; otherwise, firework types are identified

from information in victims’ reports to emergency department staff that were contained in the NEISS narrative. Illegal

firecrackers include M-80s, M-1000s, Quarter Sticks, and other firecrackers that are banned under CPSC’s FHSA

regulations (16 C.F.R. § 1500.17 (Banned hazardous substances)). Fireworks that may be illegal under state and

local regulations are not listed as illegal unless they violate the CPSC’s FHSA regulations. Estimates are rounded to

the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50 injuries are denoted with an asterisk (*). Estimates may not sum

to subtotal or total due to rounding. Percentages are calculated from the actual estimates, and they may not add to

subtotals or the total due to rounding.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

20

There were 100 fireworks-related injuries that took place at public firework displays

during 2022. Unknown fireworks devices were associated with the most injuries during the 2022

special study period. Homemade/Altered devices were involved in less than 1 percent of the

total estimated injuries during the 2022 special study period.

Gender and Age of Injured Persons

Males experienced an estimated 3.0 fireworks-related, emergency department-treated

injuries per 100,000 individuals during the special study period. Females had 1.5 injuries per

100,000 people. Figure 3 shows the distribution of estimated fireworks-related injuries by

gender.

Figure 3: Estimated Injuries by Gender: June 17 – July 17, 2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022.

Children under 5 years of age experienced an estimated 700 injuries (9.5 percent of all

fireworks-related injuries during the special study period), as shown in Figure 4 and Table 4.

Children in the 5- to 14-year-old age group experienced an estimated 1,400 injuries. Breaking

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

21

down that age group further, children 5 to 9 years of age had an estimated 600 injuries and

children 10 to 14 years of age accounted for 800 injuries.

10

Figure 4: Percentage of Injuries by Age Group: June 17 – July 17, 2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between July 17, 2022, and

July 17, 2022.

The detailed breakdown by age and gender is shown in Table 4. The concentration of

injuries among males and people under 25 years of age has been typical of fireworks-related

injuries for many years.

10

The percentages are calculated from actual injury estimates, and age subcategory percentages may not sum to the

category percentage due to rounding.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

22

Table 4

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Age and

Gender: June 17–July 17, 2022

Age Group

Total

Per 100,000

People

Male

Female

Total

7,400

2.2

4,800

2,600

0-4

700

3.8

400

300

5-14

1,400

3.4

900

500

5-9

600

3.0

300

300

10-14

800

3.8

600

200

15-24

1,800

4.2

1,100

700

15-19

1,300

6.0

800

500

20-24

600

2.8

300

300

25-44

2,700

3.0

2,000

700

45-64

700

0.8

400

300

65+

200

0.4

100

100

Sources: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. NC-EST2021-ALLDATA: Monthly Population

Estimates by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin for the United States: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2021 (With short-

term projections to December 2022). Based on the special study between June 17, 2022, and July 17, 2022. The

oldest victim was 79 years of age. Estimates are rounded to the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50

injuries are denoted with an asterisk (*). Age subcategory estimates may not sum to the category total due to

rounding.

When considering injury rates (number of injuries per 100,000 people), children and

young adults had higher estimated rates of injury than the other age groups during the 2022

special study period. Children aged 15 to 19 years had the highest estimated injury rate at 6.0

per 100,000 population. This was followed by 3.8 injuries per 100,000 people for both children

10 to 14 years of age and children ages 0 to 4 years. A general decrease is noted when

comparing the 2022 rates to the 2021 rates, except for children 15 to 19 years of age which saw

an increase from 2.9 injuries to 6.0 injuries per 100,000 people.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

23

Age and Gender of the Injured Persons by Type of Fireworks Device

Table 5 shows the ages of those injured by the type of fireworks device associated with

the injury. For children under 5 years of age, sparklers accounted for 29 percent of the total

estimated injuries for that specific age group.

11

Unknown fireworks devices accounted for 55

percent of all injuries during the special study period.

No clear relationship between age and known fireworks type is suggested by the data in

Table 5. It is worth noting that the number of estimated injuries does not completely represent

the usage pattern because victims are often injured by fireworks used by other people. This is

especially true for rockets and aerial shells (e.g., multiple tube and reloadable devices), which

can injure people located some distance away from where the fireworks are launched.

11

The percentages are calculated from the actual injury estimates.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

24

Table 5

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Device

Type and Age Group: June 17–July 17, 2022

Age Group

Fireworks Type

Total

0-4

5-14

15-24

25-44

45-64

65+

Total

7,400

700

1,400

1,800

2,700

700

200

All Firecrackers

1,300

*

200

400

600

100

*

Small

200

*

*

*

100

*

*

Illegal

500

*

*

100

300

100

*

Unspecified

700

*

200

300

200

*

*

All Rockets

400

*

*

100

300

100

*

Other Rockets

100

*

*

*

100

*

*

Bottle Rockets

300

*

*

100

200

100

*

Other Devices

1,500

300

600

200

300

*

*

Multiple Tube

100

*

*

*

100

*

*

Reloadable

100

*

100

*

*

*

*

Roman Candles

400

100

200

100

*

*

*

Novelties

200

*

100

100

*

*

*

Sparklers

600

200

300

*

100

*

*

Helicopters

100

*

*

*

100

*

*

Homemade/Altered

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

Public Display

100

100

100

Unknown

4,100

300

600

1,100

1,500

400

100

Sources: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. Estimates are rounded to the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50 injuries are denoted

with an asterisk (*). Age subcategory estimates may not sum to the category total due to rounding.

As shown previously in Figure 3, males accounted for 65 percent of the estimated

fireworks-related injuries, and females comprised 35 percent. Both males and females were

most often injured by an unknown fireworks device (57 percent for males, 51 percent for

females).

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

25

Body Region Injured and Injury Diagnosis

Figure 5 presents the distribution of estimated emergency department-treated injuries by

the specific parts of the body injured. Hands and fingers were associated with an estimated

2,200 injuries. These were followed by an estimated 1,400 injuries for both the head/face/ear

region as well as the leg region; 1,200 eye injuries; 900 trunk/other injuries; and 400 arm

injuries.

Figure 5: Body Regions Injured: June 17 – July 17, 2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. Arm includes NEISS codes for upper arm, elbow, lower arm, shoulder, and wrist. Head/Face/Ear

regions include eyelid, eye area, nose, neck, and mouth but not the eyeball. Leg includes upper leg, knee, lower leg,

ankle, foot, and toe. Trunk/other regions includes chest, abdomen, pubic region, “all parts of body,” internal, and “25-

50 percent of body.”

Figure 6 shows the diagnoses of the estimated injuries associated with fireworks

devices. Burns were associated with 2,800 estimated injuries and was the most frequent

diagnosis. Contusions, lacerations, and abrasions were associated with 2,200 estimated

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

26

injuries. Fractures and sprains accounted for 500 estimated injuries. All other diagnoses

accounted for 1,900 estimated injuries

12

Figure 6: Types of Injuries: June 17 – July 17, 2022

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. Fractures and sprains also include dislocations. “Other diagnoses” include all other injury

categories. Percentages may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

As shown in Table 6, burns accounted for over half (59 percent) of the injuries to

hands/fingers. As a single-diagnosis category, burns caused the most injuries to trunk/other

regions, arm region, and Leg region. Contusions and lacerations were the most frequent injuries

to the head/face/ear regions. Other diagnoses were most associated with injuries in the eye

region.

12

Estimated injuries may not sum to the total due to rounding. Percentages are calculated from the actual injury

estimates.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

27

Table 6

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Body

Region and Diagnosis: June 17–July 17, 2022

Diagnosis

Body Region Total Burns

Contusions/

Lacerations

Fractures/

Sprains

Other

Diagnoses

Total

7,400

2,800

2,200

500

1,900

Arm

400

300

200

*

*

Eye

1,200

*

500

*

700

Head/Face/Ear

1,400

200

800

100

200

Hand/Finger

2,200

1,300

200

200

500

Leg 1,400 600 300 100 300

Trunk/Other 900 400 200 * 200

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. Fractures and sprains also include dislocations. “Other diagnoses” include all other injury

categories. Estimates are rounded to the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50 injuries are denoted with an

asterisk (*). Estimated injuries may not sum to subtotals or totals due to rounding.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

28

Types of Fireworks Devices and Body Regions Injured

Table 7 presents estimated injuries by the type of fireworks device and body region

injured.

Table 7

Estimated Fireworks-Related, Emergency Department-Treated Injuries by Type of

Fireworks Device and Body Region Injured: June 17–July 17, 2022

Region of the Body Injured

Fireworks Type Total Arm Eye

Head/Face/

Ear

Hand/Finger Leg

Trunk/

Other

Total

7,400

400

1,200

1,400

2,200

1,400

900

All Firecrackers

1,300

100

200

100

500

200

100

Small

200

*

100

*

*

*

Illegal

500

100

100

*

200

100

*

Unspecified

700

*

100

*

300

100

100

All Rockets

400

*

*

100 100 200 *

Other Rockets

100

*

*

* * 100 *

Bottle Rockets

300

*

*

100 100 100 *

Other Devices

1,500

*

200

100

800

200

200

Multiple Tube

100

*

*

*

*

100

*

Reloadable

100

*

100

*

*

*

*

Roman Candles

400

*

100

100

300

*

*

Novelties

200

*

*

*

200

*

*

Sparklers

600

*

*

*

300 100 100

Helicopters

100

*

*

*

* * 100

Homemade/Altered

*

*

*

*

*

*

Public Display

100

*

*

100

*

100

*

Unknown

4,500

300

800

1,000

900

600

600

Source: NEISS, U.S. Consumer Product Safety Commission. Based on the special study between June 17, 2022,

and July 17, 2022. Estimates are rounded to the nearest 100 injuries. Estimates of fewer than 50 injuries are denoted

with an asterisk (*). Estimated injuries may not sum to subtotals or totals due to rounding.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

29

Most injuries resulted from fireworks devices of an unknown type; this uncertainty results

from victims’ (or parent/guardians’) inability to identify the firework device that injured them,

when asked.

Hospital Treatment

An estimated 88 percent of the victims of fireworks-related injuries in the special study

period were treated at the emergency department and then released; about 5 percent of the

victims were admitted to the hospital. Approximately 5 percent of the victims were treated and

then transferred to another hospital. The remaining 2 percent of victims had other dispositions

(i.e., left the hospital without being seen or were held for observation).

13

The percentage of

victims that were treated and admitted, held for observation, or left without being seen for

fireworks-related injuries was lower than for all consumer products in 2022. The percentages of

those “treated and released” and “treated and transferred” and were higher for the fireworks-

related injuries in the special study period than those for all consumer products.

For all injuries associated with consumer products in 2022, 85 percent of patients were

treated and released; 10 percent were admitted to the hospital; 1 percent of patients were

transferred to other hospitals; and 4 percent had other dispositions, including left hospital

without being seen, held for observation, or deceased on arrival.

14

5. Telephone Investigations of Fireworks-Related

Injuries

CPSC staff conducted in-depth telephone investigations of a sample of fireworks

incidents that occurred during the 1-month special study period surrounding the 4

th

of July

holiday (June 17, 2022, to July 17, 2022). Completed telephone investigations provided more

detail about incidents and injuries than the emergency department information summarized in

the narrative in the NEISS record. During the telephone interview, respondents were asked how

the injury occurred (hazard pattern); what medical care they received following the emergency-

department treatment; and what long-term effects, if any, resulted from their injury.

Respondents were also asked detailed questions about the fireworks involved in the incident,

including their type, markings, and where they were obtained.

13

The percentages are calculated from actual injury estimates and may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

14

Comparisons are calculated using actual injury estimates and differences may not appear due to rounding.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

30

Cases were selected for telephone investigations based on the information provided in

the NEISS narrative and coded information in the NEISS records. The selection criteria

included: (1) unusual hazard patterns, (2) severity of the injury, and (3) lack of clear information

in the narrative about the type of fireworks associated with the injury. For these reasons, and

because many victims did not respond, the telephone investigation cases cannot be considered

typical of fireworks-related injuries.

From the 171-emergency department-treated, fireworks-related injuries during the

special study period, staff selected 91 cases for telephone investigations, of which 10 were

completed and determined to be in scope, 1 was completed and determined to be out of scope,

and 80 were incomplete. Table 8 shows the final status of these investigations, including the

reasons why some investigations were incomplete.

Table 8

Final Status of Telephone Investigations

Final Case Status

Number of

Cases

Percent

Total Assigned

91

100

Completed Investigation

11

12

In Scope

10

11

Out of Scope

1

1

Incomplete Investigation

80

88

Failed to Reach Patient

41

45

Victim Name Not Provided by Hospital

31

34

Victim Refused to Cooperate

8

9

Short descriptions of the 10 completed in-scope cases are found in Appendix B. The

cases are organized in order of emergency department disposition, with Admitted (to the

hospital) first, followed by Treated and Released, and Left without Being Seen by a Doctor.

Within dispositions, cases are in order of increasing age of the victim.

Summary Statistics

Of the 10 completed in-scope cases, 7 involved males, and 3 involved females. There

were four victims aged 5 to 14 years old; four victims aged 15 to 33 years old; and two victims

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

31

aged 34 to 59. Two victims were admitted to the hospital, seven victims were treated and

released, and one victim left without being seen.

The fireworks devices consisted of four reloadable aerial shells,

15

one roman candle, one

small firecracker, one novelty device, and three unspecified devices.

The distribution of the types of fireworks and the emergency department dispositions

differs from the special study data in Section 4. These differences reflect the focus in the

telephone investigations into more serious injuries and incomplete NEISS records. Twelve

percent of the victims selected for the telephone interviews completed the survey.

Hazard Patterns

The hazard patterns described below are based on the incident descriptions obtained

during the telephone investigations and summarized in Appendix B. When an incident had two

or more hazard patterns, staff selected the hazard pattern most likely to have caused the injury.

Hazard patterns are presented in Table 9 below, and a detailed description of the incidents

follows Table 9. Case numbers refer to the case numbers shown in Appendix B.

Table 9

Hazard Patterns as Described in Telephone Investigations for Fireworks-Related

Injuries

Hazard Pattern

Number of In-scope

Cases

Percent of Total

Total Cases

10

100%

Malfunction

5

50%

Misfire

3

30%

Errant Flightpath of Debris

2

20%

Misuse

5

50%

Improper Preparation

5

50%

15

The category “aerial shells” includes multiple tube, reloadable mortars, and rockets, but excludes bottle rockets.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

32

Malfunction (5 Victims, 50 percent of total)

Misfire

• Case 1: A 19-year-old male victim was with friends when they decided to set off a roman

candle-type device. Once the victim lit the device it immediately exploded hitting the

victim in the face. The victim went back to his car and witnesses took him to the

emergency department. Once arriving plans were made to transfer the victim to a nearby

hospital that was better equipped for the emergency eye surgery the victim needed. The

victim underwent eye surgery which involved the layers of his cornea being peeled back

to clean out the debris. The victim also had a cut on his forehead that required stitches.

The victim fully recovered from the eye surgery after two weeks and the injury to his

forehead healed after 1 month. There are no long-term consequences expected

because of the incident.

• Case 2: A 49-year-old male victim was lighting a mortar-style device when the firework

shot out of the side of the tube. The victim was taken to the emergency department

where he was treated for a grade 5 liver blast injury, right colon contusions, diaphragm

injury, right lung contusions, blast injury to both hands, and hemorrhagic shock. The

victim lost his right thumb, two ribs, and his spleen because of the event. The victim’s

wounds were cleaned, stitched, and cast by medical professionals. The victim reported

that his wounds took 6 months to heal properly.

• Case 7: A 23-year-old male victim was lighting a multiple tube device when the firework

immediately detonated. The device blew up in the victim’s face and burned his hands

and right arm. The victim attempted to treat himself with over-the-counter products but

decided to go to the emergency department the next morning. Once there, emergency

personnel cut the burns open and cleaned and bandaged the area. The victim saw a

burn specialist three days later and was given cream and an antibiotic for the wounds.

He was also supplied with bandages, wraps, and an arm band to protect the wound from

sun exposure. The victim returned to the burn specialist weekly to change bandages,

clean the wounds, and refill prescriptions. The victim fully recovered after 3 months. The

victim has no long-term consequences besides a lighter complexion to the healed burn

wounds.

Errant Flightpath of Debris

• Case 6: A 13-year-old female victim was with family watching neighbors set off

fireworks. The victim was approximately 8 feet away from the device when she felt a

“little pinch” on her left leg. It is believed that lit debris fell from the sky and landed on the

victim’s leg, although she had long sweatpants on. The victim was taken to the

emergency department where medical professionals cleaned and wrapped the wound.

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

33

The victim’s parents stated that it took 6 months for the injuries to fully heal. The victim is

not expected to suffer long term consequences from the event.

• Case 10: A 33-year-old female victim was at a sporting event where they were

performing a firework show after the game. The victim was looking up at the fireworks

when debris landed into her eyes. The victim left the area and went to get help and

water. Flushing the debris did not help and the victim went to the emergency

department. Medical professionals dilated both eyes and gave numbing drops to the

victim. The victims eyeball lens was inspected for damage. Medical professionals

prescribed medication for the damage to both corneas. The victim was discharged and

was told not to rub their eyes and not to drive until the eye fully healed. The victim stated

that it took them 5 days to recover from their injuries. The victim is not expected to suffer

long term consequences from the incident.

Misuse (5 Victims, 50 percent of total)

Improper Preparation

• Case 3: A 5-year-old male victim was helping their father light an unknown firework

device when a foreign body entered his eye from the sparks. The victim was taken to the

emergency department where medical professionals flushed and examined the eye. It

was determined that no damage occurred, and the victim was released. The victim’s

parents stated that the injury fully healed in less than 24 hours. The victim is not

expected to suffer long term consequences from the incident.

• Case 4: A 6-year-old male victim was with an older sibling when they found small

firecracker devices. The older child put two of the devices together and topped them with

gunpowder and told the victim to light the devices. The parent, who was not present,

saw the victim rubbing his face and saw the skin peeling off. The mother brought the

child inside and threw cold water in his face and called 911. Paramedics arrived and

took the victim to the emergency department. At the emergency department the victim

was given pain medication as well as burn cream to apply to the wounds at home. The

mother stated that it took about a week for the skin to heal and a month for the victims’

eyelashes to grow back. The mother stated that the injuries are no longer visible, and no

long-term consequences are expected.

• Case 5: A 14-year-old male victim lit a smoke bomb device in his hand when it exploded.

The victim was in pain and immediately ran to his grandmother. The grandmother put

cold water on the injury and called the victim’s mother. When the mother arrived, she

placed an ice pack on the injury and drove the victim to the hospital. At the hospital

medical professionals gave the victim pain medication and cleaned the wound and was

released. The victim attended physical therapy twice to “stretch” the skin around the

THIS DOCUMENT HAS NOT BEEN REVIEWED

OR ACCEPTED BY THE COMMISSION

CLEARED FOR PUBLIC RELEASE

UNDER CPSA 6(b)(1)

2022 Fireworks Annual Report | June 2023 | cpsc.gov

34

thumb to maintain full mobility. The victim is not expected to suffer long term

consequences from the incident.