BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION | JANUARY 2019

Ability

-to-Repay and

Qualified Mortgage Rule

Assessment Report

1 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Message from

Kathleen L. Kraninger

Director

The Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection is pleased to publish this report containing the

results of its assessment of the Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Rule that the Bureau

issued in 2013 to implement provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act amending the T ruth in Lending

Act. The provisions were designed to assure that consumers are offered and receive residential

mortgage loans on terms that reasonably reflect their ability to repay the loans.

Separately, section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Bureau to conduct an

assessment of each significant rule or order adopted by the Bureau under Federal consumer

financial law. This report has been prepared to satisfy that statutory obligation.

This somewhat unique statutory requirement places a responsibility on the Bureau to take a

hard look at each significant rule it issues and evaluate whether the rule is effective in achieving

its intended objectives, and the purposes and objectives of Title X of the Dodd-Frank Act, or

whether it is having unintended consequences. I see this as a valuable opportunity to assure that

public policy is being pursued in an efficient and effective manner and to facilitate making

evidence-based decisions in the future on whether changes are needed.

The Bureau’s Office of Research took the lead in conducting this assessment. The Bureau’s

researchers began work over two years ago in identifying the questions that needed to be asked

and in exploring the available data sources to answer those questions. The researchers then

developed research plans and solicited public comment on such plans and other information.

The researchers determined that although public and commercially-available data, along with

the National Mortgage Database which the Bureau has developed in collaboration with the

Federal Housing Finance Agency, could be used to examine the effects of the rule on the market

as a whole, those data were insufficient to examine specific market segments where the rule

might have had its largest effect. Accordingly, the Bureau obtained, among other things, a

unique dataset comprised of de-identified, loan-level data from a number of creditors to fill this

gap. The Bureau’s researchers supplemented those data with a survey to which over 175 lenders

2 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

responded along with data from a survey conducted by the Conference of State Bank

Supervisors.

Through rigorous statistical analyses of the quantitative data and a careful review of the

qualitative data and public comments received in response to the Bureau’s Request For

Information, the Bureau has produced this comprehensive assessment report. I am confident

that this report provides numerous useful findings and insights for stakeholders, policy makers,

and the general public about developments in the origination of mortgages and the effects of the

rule on the availability and cost of credit.

The issuance of this report is not the end of the line for the Bureau. I am committed to assuring

that the Bureau uses lessons drawn from the assessments to inform the Bureau’s approach to

future rulemakings. We are interested in hearing reactions from stakeholders to the report’s

methodology, findings and conclusions. The Bureau anticipates that continued interaction with

and receipt of information from stakeholders about this report will help inform the Bureau’s

future assessments as well as its future policy decisions regarding this rule.

Sincerely,

Kathleen L. Kraninger

3 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Table of Contents

Message from Kathleen L. Kraninger ............................................................................1

Table of Contents ..............................................................................................................3

Executive Summary .........................................................................................................6

1. Introduction ..............................................................................................................15

1.1 Purpose and scope of the assessment ..................................................... 19

1.2 Methodology and plan for assessing effectiveness ................................. 29

1.3 Sources of information and data ............................................................. 32

2. The ATR/QM Rule ....................................................................................................36

2.1 Statutory background .............................................................................. 36

2.2 ATR/QM Rule background ..................................................................... 38

2.3 Overview of ATR/QM Rule requirements .............................................. 42

3. Market overview .......................................................................................................49

3.1 The development of the modern mortgage market ................................ 50

3.2 Early 2000s mortgage market expansion............................................... 56

3.3 Financial crisis and Great Recession: 2007-2009 ................................. 63

3.4 Pre-Rule economic recovery: 2009-2013 ............................................... 67

3.5 Mortgage market pre- and post-Rule...................................................... 69

3.6 Compliance with the Rule ....................................................................... 79

4. Assuring the ability to repay..................................................................................82

4 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

4.1 Ability to repay and loan performance ................................................... 83

4.2 Loans with restricted features ................................................................. 84

4.3 Historical trends in DTI and relationship with loan performance ........ 96

4.4 Effects of the General QM DTI limit on loan performance.................. 106

5. Effects of the Rule on access to mortgage credit and cost of

credit ........................................................................................................................116

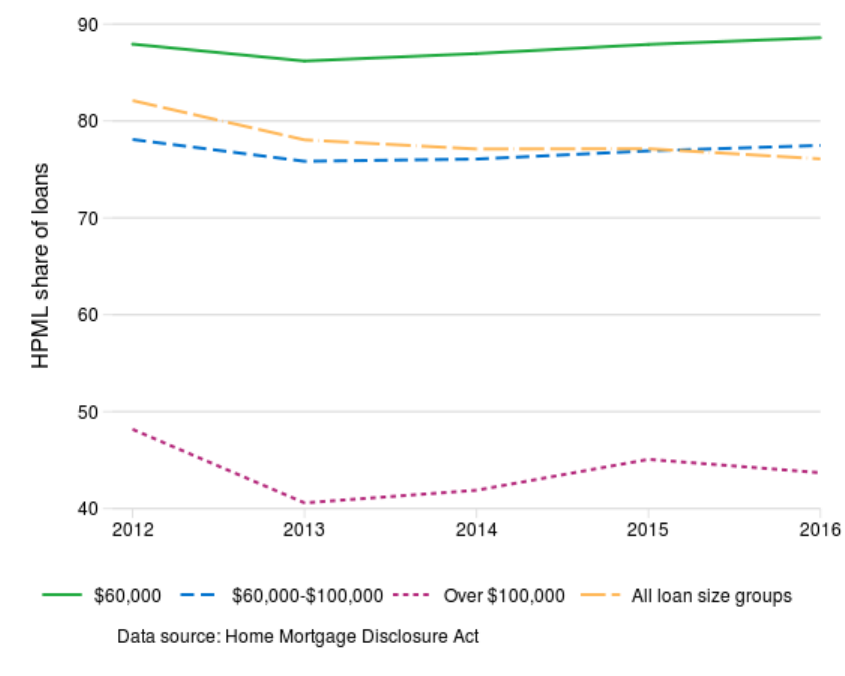

5.1 Market trends in origination of loans with DTI greater than 43 percent119

5.2 Evidence from the lender survey........................................................... 123

5.3 Effect of the Rule on access to credit for borrowers with DTI greater

than 43 percent: evidence from the Application Data ..........................131

5.4 Effects of the points and fees requirement on the availability of small

dollar loans and cost of credit ............................................................... 163

5.5 The rebuttable presumption provision ................................................. 180

6. The Temporary GSE QM .......................................................................................188

6.1 Background ............................................................................................ 189

6.2 Conforming originations since the implementation of the Rule ..........191

6.3 Functional features of the Temporary GSE QM requirements ............ 192

6.4 Meeting the goals of the QM requirements ..........................................204

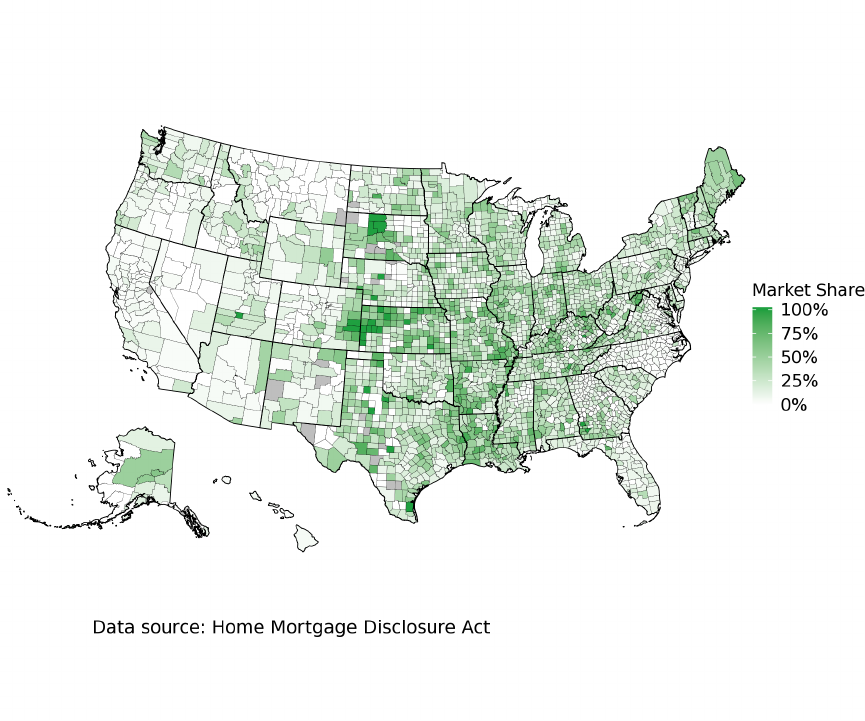

7. Analysis of the small creditor QM category ......................................................207

7.1 Background ............................................................................................ 208

7.2 Analysis using HMDA data ................................................................... 210

7.3 Evidence from CSBS survey data .......................................................... 223

8. Additional effects of the Rule ..............................................................................229

8.1 Effect on closing times........................................................................... 229

8.2 Survey evidence ..................................................................................... 231

Appendix A: The Rule and Bureau purposes and objectives ...........................235

5 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Introduction .................................................................................................... 235

Purposes .......................................................................................................... 235

Objectives ........................................................................................................ 238

Appendix B: Comment summaries .......................................................................242

Evidence about ATR/QM Rule effects ........................................................... 243

Recommendations to modify, expand, or eliminate the ATR/QM Rule ...... 254

The assessment plan ....................................................................................... 263

Appendix C: Application data request to nine lenders ....................................267

6 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Executive Summary

The mortgage market has been a key to homeownership for an increasing number of American

families since the middle of the 20th century.

T he Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) amended

the T ruth in Lending Act (T ILA) in 2010 to place certain new obligations on the origination of

consumer mortgages. T he Dodd-Frank Act also directed the Bureau of Consumer Financial

Protection (Bureau) to issue rules to effectuate c ertain amendments and authorized the Bureau

to prescribe rules as may be necessary or appropriate to enable the Bureau to administer and

carry out the purposes and objectives of T ILA. The Bureau’s initial rule and certain changes to

that rule, which this report refers to collectively as the Ability-to-Repay/Qualified Mortgage

(AT R/QM) Rule or Rule, came into effect in January 2014.

1

Section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Bureau to conduct an assessment of each of

its significant rules and orders and to publish a report of each assessment within five years of

the effective date of the rule or order. The Bureau has determined that the ATR/QM Rule is a

significant rule. The Bureau developed plans for assessments in 2015 and began work on the

ATR/QM Rule assessment in 2016. Pursuant to decisions made at that time, although this

assessment addresses matters relating to the costs and benefits of the Rule, this report does not

include a benefit-cost analysis of the Rule or parts of the Rule. For Section 1022(d) assessments

that the Bureau undertakes going forward, the Bureau in its discretion is reconsidering whether

to include benefit-cost analysis in its assessment and its published report. The Bureau expects

that this report will inform the public about the effects of the Rule and will help inform the

Bureau’s future policy decisions concerning mortgage originations including whether to

commence a rulemaking proceeding to make the Rule more effective in protecting consumers,

less burdensome to industry, or both.

The key requirement of the Rule is that lenders must make a reasonable and good faith

determination, based on verified and documented information, that the consumer has a

1

For a full definition of t he ATR/QM Rule, see Chapters 1 and 2.

7 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

reasonable ability to repay (ATR) before issuing a residential mortgage loan. The Rule defines

certain factors that a lender must consider in making such a determination and requires that the

determination must be made using a payment schedule that fully amortizes the loan over the

term of the loan. Lenders who are found to be non-compliant with this requirement can be held

liable for damages under TILA. In addition, non-compliance can be asserted as a matter of

defense by recoupment or setoff in a foreclosure proceeding.

The Rule also defines the category of Qualified Mortgage (QM) loans and provides that QM

loans are presumed to comply with the ATR requirement. In most cases, the presumption is

conclusive (i.e. a safe harbor). However, for “high cost” loans—a term whose definition largely

tracks one developed by the Federal Reserve Board as a proxy for subprime loans—the

presumption is rebuttable, allowing the consumer the opportunity to prove that the lender in

fact failed to make a reasonable determination of the consumer’s repayment ability.

All QM loans must be fully amortizing loans with terms no greater than thirty years and (except

for loans under $100,000) cannot have the sum of points and fees exceed 3 percent of the loan

amount. Additionally, to meet the Rule’s General QM test, the ratio of monthly debt obligations

to income cannot exceed 43 percent (“debt to income ratio,” or “DTI”). For this test, DTI must

be calculated in accordance with the provisions of the Rule’s Appendix Q which incorporates the

FHA underwriting standards from 2013 for calculating debt and income. The Rule creates a

temporary category under which loans eligible for purchase or guarantee by Fannie Mae or

Freddie Mac (the Government Sponsored Enterprises, or GSEs) generally qualify as QM loan.

This exception (the Temporary GSE QM) is scheduled to expire seven years after the effective

date of the Rule (or earlier if the GSEs cease to be in conservatorship). In addition, mortgages

eligible for purchase or guarantee by the Federal Housing Authority (FHA), Veterans

Administration (VA), or Rural Housing Service (RHS) are QMs by virtue of separate regulations

issued by those agencies pursuant to separate Title XIV rulemaking authority under the DFA.

Key Findings

The collapse of the housing market in 2008 sparked the most severe recession in the United

States since the Great Depression. As documented in this report, the years prior to the collapse

were marked by an increased share of lending going to borrowers of lower creditworthiness and

to new loan product types associated with higher risk.

8 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

A number of different theories have been advanced as to why the housing market collapsed. In

the report that the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in

the United States

2

issued after the Dodd-Frank Act was enacted the majority pointed to

“dramatic failures of corporate governance and risk management,” “excessive borrowing, risky

investments and lack of transparency,” and “widespread failures in financial regulation and

supervision” as key causes.

3

A minority report by one commissioner concluded that

“government housing policy” was responsible for “fostering the growth of a bubble of

unprecedented size and an equally unprecedented number of weak and high-risk residential

mortgages.”

4

A separate minority report by three other commissioners disagreed with both

views and identified ten causes, some global and some domestic, as essential to explaining the

financial and economic crisis.

5

Since the issuance of the Commission’s report there has been a

vast body of academic literature seeking to explore the contributing causes of the crisis.

6

It is

beyond the scope of this report to address the question of what caused the housing market to

collapse a decade ago.

The provisions of the Dodd-Frank Act described above and that are the subject of this report

were enacted for the stated purpose of “assur[ing] that consumers are offered and receive

residential mortgage loans on terms that reasonably reflect their ability to repay.”

7

This report

2

The Commission was created in May, 2009 by P.L. 111-21 and issued its r eport i n January, 2011. Six m embers of the

Com m ission w ere appointed by the Dem ocratic l eadership of C ongress and four by the Republican leadership. The

m a jority r eported was joined by the six m embers a ppointed by the Dem ocratic l eadership; three m embers

a ppoi nted by the Repub lican l eadership joined on e di ssent and the fourth authored a separate dissent.

T h e Financial C risis In quiry Report at xviii - x x ii (2 011) .

4

Id. at 444.

5

Id. a t 445-448.

6

For a n on-exhaustive list of additional literature on the causes of the crisis, see Adelino, Manuel, Antoinette Schoar,

a n d Felipe S everino. "Loa n originations a nd defaults in the mortgage crisis: The r ole of t he m iddle c lass." T he

Rev iew of Financial Studies 2 9.7 (2016); Amrom in, G ene, et a l. "C om plex m ortgages." Rev iew of Finance 2 2.6

(2 018); Avery, Rob ert B. , and Kenneth P. Br evoort. "The subprim e c risis: Is g ov ernment housing policy to b lame?"

Rev iew of Economics and Statistics 97.2 (2015); Bubb, Ryan, and Alex Kaufman. “Securitization and moral hazard:

Ev idence from credit score cutoff rules.” 63, 1-1 8 (Apr. 2014); Case, Karl E., Robert J. Shiller, and Anne Thom pson.

“ W hat have they been thinking? Hom e buyer b ehavior in hot and col d m arkets.” National Bureau of Econom ic

Research Working Paper #18400 (2012); Chen g, In g-Haw, and Sahil Raina, and Wei Xiong. “Wall Street and the

Hou sing Bu bble.” 104(9): 2797-2829 (2014); Corbae, Dean, and Erwan Quintin, "Leverage and the Foreclosure

Cr i si s, " Journal of Politica l Ec on om y 1 23 , n o. 1 ( Fe b. 2 015 ); Foote, Christ opher L., Kri st opher S. Gerardi, and Paul S.

Willen. “Why Did So Ma ny People Ma ke So Many Ex Post Bad Decisions? The Causes of the Foreclosure Crisis.”

Na tional Bureau of Econom ic Research Working Paper #18082 (2012); Lee, Don ghoon, C hristopher May er, and

Joseph Tracy. “A New Look a t Second Liens.” Federal Reserve Bank of New Y ork S taff Reports (2 012); Mian, Atif,

a n d Amir Sufi. "Fr audulent incom e ov erstatem ent on m ortgage applications during the credit expansion of 2002 to

2 0 05." T he Rev iew of Financial Studies 30.6 (2017); Pa lmer, Christopher, “Why Did S o Ma ny Subprim e Borrowers

Defa u lt During the Crisis: Loose Credit or Plummeting Prices?” (Sept. 24, 2015).

7

TILA § 1 29B(a)(2), 15 USC § 1 639b(a)(2).

9 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

does not address the necessity of the new TILA requirements or the merits of possible

alternative ways that Congress might have responded to the housing collapse, but rather, as

required by the Dodd-Frank Act, assesses the effectiveness of the ATR-QM Rule that

implemented those requirements.

Assuring Ability to Repay

A primary purpose of the Rule is to prevent the extension of mortgage credit for which

consumers lack the ability to repay, based on information available at the time of origination.

The report finds that approximately 50 to 60 percent of mortgages originated between 2005 and

2007 that experienced foreclosure in the first two years after origination were mortgage loans

with features that the ATR/QM Rule generally eliminates, restricts, or otherwise excludes from

the definition of a qualified mortgage, such as loans that combined low initial monthly payments

with subsequent payment reset or those made with limited or no documentation of the

consumer’s income or assets. Loans with these features had largely disappeared from the market

prior to the adoption of the Rule, and today they appear to be restricted to a limited market of

highly credit-worthy borrowers.

Further, this report finds that loans with higher debt to income ratios—which is a factor

generally required to be considered in making ATR determinations and is one of the criteria

used to define the General QM category—are historically associated with higher levels of

delinquency, after controlling for other relevant borrower characteristics (even though the

strength of the relationship depends on the economic cycle). In the conventional mortgage

market—which encompasses all mortgages other than those purchased or guaranteed by a

government agency—DTI ratios are constrained from returning to crisis-era levels by a

combination of the ATR requirement, GSE underwriting limits which define the loans which are

eligible for purchase by the GSEs (currently, a DTI limit of 45 percent applies to most loans) and

the Bureau’s General QM DTI threshold which limits the General QM category to loans with

DTIs at or below 43 percent. Even though house prices have largely returned to pre-crisis levels,

currently five to eight percent of conventional loans for home purchase have DTI exceeding 45

percent; in contrast, approximately 24 to 25 percent of loans originated in 2005 – 2007

exceeded that ratio.

Even though it is not possible for the Bureau to directly observe the ability to repay at

origination, an analysis of realized loan performance across a wide pool of loans can be

informative. Among other metrics, this report examines the percentage of loans becoming 60 or

more days delinquent within two years of origination. The analysis finds that the introduction of

the Rule was generally not associated with an improvement in loan performance according to this

metric.

10 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

In part, this is due to the fact that delinquency rates on mortgages originated in the years

immediately prior to the effective date of the Rule were historically low, as credit was already

tight at that time. The delinquency rate of loans with DTIs exceeding 43 percent made under the

Rule’s ATR underwriting requirements (non-QM loans) remained steady at 0.6 percent; the

delinquency rate of GSE loans with DTIs above 43 percent increased from 0.6 percent for loans

originated in 2012-2013 to 1.0 percent among 2014-2015 originations. Thus, although the

performance of non-QM loans did not improve in absolute terms, it has improved relative to the

performance of comparable QM loans. (Chapter 4)

Access to Credit and Restrictions on Unaffordable Loans

Looking at the market as a whole, there was not a significant break in the volume of mortgage

applications or the average approval rate at the time the Rule became effective. This is

attributable in part to the fact that, as noted, following the financial crisis and before the Rule

took effect credit had tightened substantially and in part to the breadth of the definition of QM

and the safe harbor afforded to most QM loans. The Bureau estimates that 97-99 percent of

loans originated in 2013, the last year prior to the effective date of the Rule, would have satisfied

QM requirements. As explained above, if a loan is a QM loan, it is presumed to meet the Rule’s

ATR requirement, and, therefore, the ATR requirement would not separately decrease access to

credit for borrowers who qualify for a QM loan.

There are, however, certain segments of the market where the Rule is more likely to have

affected access to credit and the Report focuses on those segments.

• Borrowers with high debt to income ratios – For high DTI borrowers—defined

here to mean borrowers with a DTI above 43 percent—who qualify for a loan eligible for

purchase or guarantee by one of the GSEs (or one of the federal agencies), the Rule has

not decreased access to credit since such mortgages meet the standard for QM loans. In

fact, the evidence suggests that the GSEs may have loosened their underwriting

requirements for high DTI borrowers, as evidenced by recent trends (Chapter 6)

There is a segment of high DTI borrowers seeking loans which are not eligible for GSE

purchase (or a government purchase or guarantee), most commonly due to loan size.

Generally, such loans are non-QM loans as they cannot meet the General QM standard

and thus are subject to the ATR provisions. The Bureau’s analysis of detailed application

data from nine larger lenders (further, “Application Data”) indicates that the Rule

displaced between 63 and 70 percent of approved applications for home purchase among

non-QM High DTI borrowers during the period of 2014 – 2016; this translates into a

11 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

reduction of between 1.5 and 2.0 percent of all loans for home purchase made by these

nine lenders during this period. Evidence from other data sources, including a survey of

mortgage lenders that the Bureau conducted as part of this assessment (further, Lender

Survey) and recent research by the Federal Reserve Board and academic economists

likewise points to sharp reductions in access to credit among this category of borrowers

following the implementation of the Rule. Notably, results in the refinance category are

quite different. For non-QM, High DTI borrowers seeking to refinance their loans, the

Application Data points to an initial reduction in access to credit in 2014, followed by

gradual improvement in the years after. T his is consistent with a notion that consumers

seeking to refinance a mortgage having already demonstrated some ability to repay,

thereby lowering ATR risk and making lenders more likely to extend credit. (Chapter 5)

The Application Data also indicates that among the non-QM High DTI borrowers

seeking to purchase homes, approval rates declined across all credit tiers and income

groupings, with the result that the average credit score and income for declined

applicants increased after the Rule took effect. Further, more broad-based industry data

indicates that despite tightening of credit, delinquency rates for non-QM High DT I

borrowers did not decrease after the Rule took effect. Together, these findings suggest

that the observed decrease in access to credit in this segment was likely driven by

lenders’ desire to avoid the risk of litigation by consumers asserting a violation of the

ATR requirement or other obligations or risks associated with that requirement, rather

than by rejections of borrowers who were unlikely to repay the loan. (Chapter 5)

• Self-employed borrowers – As with high DTI borrowers, the Rule did not impact

access to credit for self-employed borrowers seeking a mortgage which is eligible for

purchase or guarantee by one of the GSEs or federal agencies. In contrast, self-employed

borrowers who do not qualify for a loan eligible for purchase or guarantee by one of the

GSEs or federal agencies generally need to qualify under the General QM standard in

order to obtain a QM loan. Responses to the Lender Survey indicate that specifically for

self-employed borrowers, lenders may find it difficult to comply with Appendix Q

relating to the documentation and calculation of income and debt. However, the

Application Data indicates that the approval rates for non-High DT I, non-GSE eligible

self-employed borrowers have decreased only slightly, by two percentage points.

(Chapter 5)

• Borrowers seeking smaller loan amounts: The points-and-fees cap on QM loans

has potential implications for borrowers seeking smaller loan amounts because, to the

extent there are fixed costs in originating mortgages, those costs will constitute a higher

percentage of the loan amount for smaller loans relative to larger loans. The Bureau’s

12 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

analysis of HMDA data indicates, however, that the Rule likely had no effect on access to

credit for such loans. This is consistent with responses to Lender Survey which indicate

that applications for which the points and fees limit will be exceeded are sufficiently rare

that lenders handle them on a case-by-case basis. Specifically, lenders typically waive

certain fees, with or without a compensating increase in the interest rate, to avoid

exceeding the cap. Lenders denying an application to avoid exceeding the QM points and

fee cap is rare. (Chapter 5)

Creditor Costs and the Cost of Credit

The Rule introduces certain requirements for documenting income and debt that may differ

from the pre-Rule practices for some lenders. For non-QM loans (as well as high cost QMs), the

Rule also creates potential liability for ATR violations. Furthermore, under a separate rule

administered by other agencies, holders of non-QM loans are required to hold extra capital

against such loans which can add to the cost of funding these loans. The Report examines the

effect of the Rule on lenders’ costs of originating loans and on the prices they charged to

consumers.

At the aggregate market level, the Rule does not appear to have materially increased costs or

prices. A periodic survey conducted by the Mortgage Bankers Association among non-bank

lenders indicates that the costs of originating mortgage loans have increased over the past

decade but that there was not a distinct increase around the time of the implementation of the

Rule. Similarly, the Bureau’s analysis indicates that the spread between the average interest rate

on 30-y ear fixed-rate mortgages over the relevant Treasury rate has remained constant since the

implementation of the Rule. (Chapter 3)

The Bureau would not be able to reasonably obtain evidence that directly measures the extra

cost of originating a loan that may have been created by the Rule. Instead, the Bureau has

obtained qualitative feedback through responses to the Lender Survey, regarding material

changes in credit policy that have occurred. A majority of respondents indicated that their

business model has changed as a result of the Rule. Among those respondents who reported

changed business model, some respondents pointed to increased income documentation or

increased staffing, while others mentioned adopting a policy of not originating non-QM loans.

The Bureau has utilized the Application Data to quantify the cost in the form of foregone profits

from not originating certain non-QM loans; it is found that among the nine lenders that

provided the data, the lost profits amounted to between $20 and 26 million per year.

Focusing specifically on non-QM loans, evidence is mixed as to whether the Rule has increased

the price of such loans. None of the nine lenders that provided Application Data charge extra for

13 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

non-QM loans specifically and a review of retail rate sheets of approximately 40 lenders revealed

that an extra adjustment for non-QM loans is very infrequent. Nevertheless, 23 out of 204

respondents to the Lender Survey that the Bureau conducted for this assessment indicated

applying such an increase and recent research by the Federal Reserve Board finds that loans

with DT Is above 43 percent are substantially more expensive than similar loans with DTIs at or

below 43 percent. (Chapter 5)

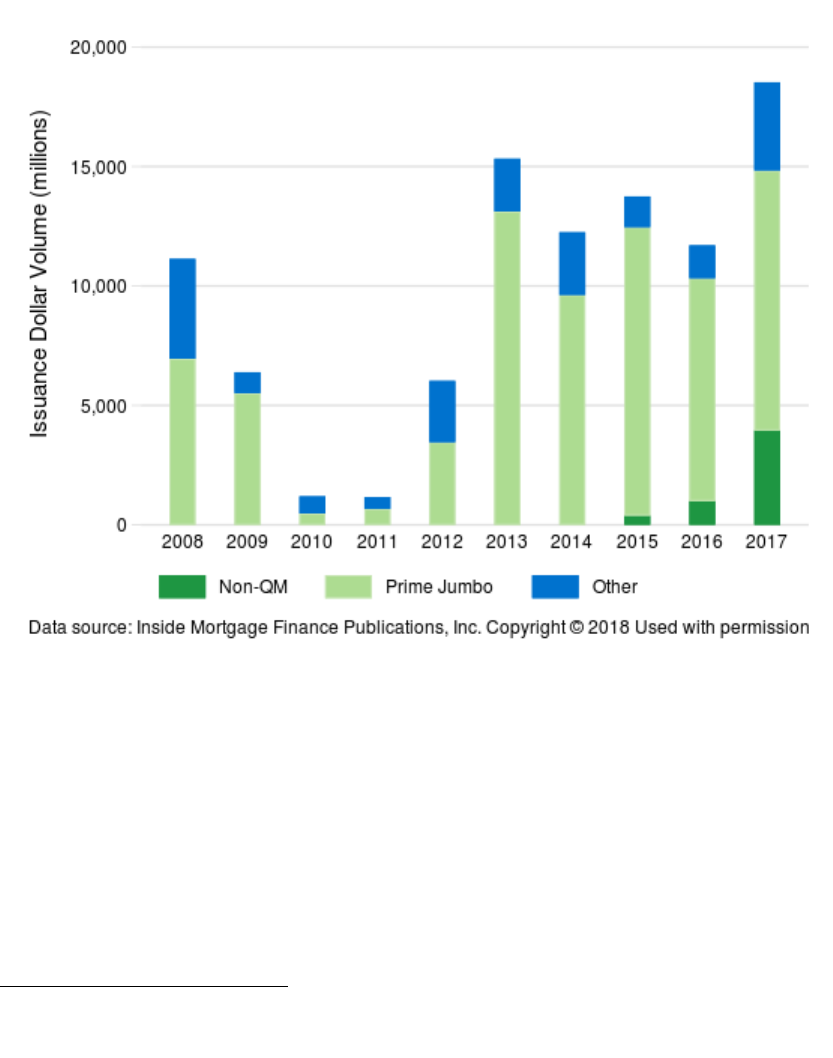

Effects on Market Structure

To a large extent, the current QM category is broad due to the inclusion of loans eligible for

purchase by the GSEs. The inclusion of such loans in the QM category is temporary and is set to

expire by January 2021. Contrary to the Bureau’s expectations at the time of the rulemaking, the

GSEs have maintained a persistently high share of the market in the years following the Rule’s

effective date. The private label mortgage-backed securities market, where investors purchase

loans that are not insured or guaranteed by GSEs or government agencies, remains small

relative to GSE securitizations and primarily provides funding for QM loans made to prime

jumbo borrowers (although recently there has been a number of non-QM securitizations based

on loans made to other types of borrowers). The dominance of GSEs in the conventional loan

segment may be attributable to a range of factors which distinguish GSE loans from those made

under the General QM and ATR criteria, potential advantages in compliance certainty and

flexibility, and robust secondary market liquidity. (Chapter 6)

The Bureau has examined whether the Temporary GSE QM provision of the Rule has caused in

an increased reliance on GSEs’ Automated Underwriting Systems (AUSs) for loans that are not

sold to the GSEs. T he analysis of submissions to AUSs shows no immediate increase in the

aggregate volume of submissions relative to the volume of loans purchased by GSEs. However,

the data do suggest a somewhat higher use of the GSEs’ AUS in recent years, particularly for

loans which do not fit within or are more difficult to document within the General QM

underwriting standards, such as loans made to self-employed borrowers. (Chapter 6)

The Rule contains certain provisions for smaller lenders that allow them to originate High DT I

loans, and in some cases, balloon loans as long as such loans are held on portfolio for at least

two years after the origination by small creditors (Small Creditor QM and Small Creditor

Balloon QM, respectively). Among HMDA reporting depository institutions involved in

mortgage lending in 2016, approximately 90 percent meet the definition of Small Creditor and

these institutions account for about 24 percent of mortgage loans. T he Rule does not appear to

be constraining the activities of these lenders since virtually all fall well below the threshold that

defines Small Creditor. There are systematic differences in the loans made by Small Creditors

14 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

and non-Small Creditors. The former hold a larger share of their originations on portfolio,

although there was a noticeable decline in the share of portfolio loans made by small creditors in

2016 which coincided with an expansion in the definition of small creditor. Similarly, a larger

share of small creditor mortgages are made in rural counties or to finance manufactured

housing mortgages. Small creditors responding to a survey conducted by the Conference of State

Banking Supervisors (CSBS) in 2015 reported that a larger share of their portfolio loans were

non-QM loans than was true for the larger lenders who responded to the survey, and also

reported declining a smaller percentage of applications than larger creditors. To the extent small

creditors declined applications, these creditors were less likely than larger creditors to attribute

their denial to the requirements of the Rule than larger creditors. (Chapter 7)

15 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

1. Introduction

The mortgage market is the single largest market for consumer financial products and services

in the United States, with approximately $10.7 trillion in consumer mortgage loans

outstanding.

8

During the first decade of the 21st century, this market went through an

unprecedented cycle of expansion and contraction. When the housing market collapsed in 2008,

it sparked the most severe recession in the United States since the Great Depression.

9

An early warning sign of the approaching mortgage crisis was an upswing in early payment

delinquencies and defaults.

10

For mortgage originations between 2000 and 2004, 1.7 percent

would become 60 or more days delinquent within the first year.

11

For the 2006 vintage, the

figure was 5.4 percent. Expanding to the first two years of repayment, the growth in

delinquencies was more severe. For mortgages made in 2005, 2006, and 2007, 6.0 percent, 1 3.0

percent, and 14.4 percent became 60 or more days delinquent within the first two years,

respectively. These rates are substantially above the average between 2000 and 2004 of 3.6

percent. As the economy worsened, the share of loans with serious delinquencies (90 or more

days past due or in foreclosure) grew further. For loans with atypical features that became

common during the mid-2000s, the rates of serious delinquency were particularly high. By the

end of 2010, among loans originated from 2005 to 2007, 35.5 percent of short-reset adjustable-

rate mortgages, 29.7 percent of interest only loans, and 27.1 percent of loans with limited or no

documentation were or had been seriously delinquent. Some of those delinquencies may have

resulted from an unanticipated deterioration in the borrowers’ economic situation after the

loans were originated. But the high rate of early delinquencies suggests that for some portion of

8

Fed. Reserve Sy stem, Mor tgage Debt Outstanding,

h t tps://w ww .federalreserve.gov/data/m ortoutstand/current.htm (last visited Dec. 1 3, 2018).

9

See T h om as F . S iem s, Branding the Great Recession, at 3, Fin. In sights (Fed. Reserve Bank of Dall., May 2012),

available at https://www.dallasfed.org/~/media/documents/outreach/fi/2012/fi1201.pdf

(stating that the [great recession]

‘‘was the longest and deepest economic contraction, as measured by the drop in

real GDP, since the Great Depression.’’).

10

Ea r ly payment defaults are g enerally defined a s borrowers being 60 or more days delinquent within the first year.

How ever, where noted, this discussion also uses a more expansive definition of early payment default to include 60

days delinquent within the first two y ears.

11

All statistics in this paragraph are Bureau calculations using the National Mortgage Database.

16 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

the borrowers, the loans may have been beyond their ability to repay, either from the start or

shortly thereafter.

The impact of these high rates of delinquency and default was severe on consumers and

communities,

12

on creditors

13

who held loans on their books, and on private investors who

purchased loans directly or indirectly through certain types of securitizations.

14

Because the risk

from these products was spread throughout the financial system,

15

a severe credit shock

disrupted the American economy. The Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Mae) and

the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac), which supported the mainstream

mortgage market, experienced heavy losses and were placed in conservatorship by the federal

government in 2008 to support the collapsing mortgage market.

16

House prices, which had risen

27 percent nationally between 2003 and 2007,

17

fell an average of 33 percent from their peak in

2006,

18

and delinquency and foreclosure rates remained elevated

19

for several years.

12

See 7 8 Fed. Reg. 6408, 6559–6560 (Jan. 30, 2013).

13

T h e term “ creditor” and “l ender” are used interchangeably in this report.

14

“ A larmed by the unexpected delinquencies and defaults that began t o appear in mi d-2 007, i nve stors f l ed t he m ulti-

t r illion dollar market for m ortgage-backed securities (MBS ), dropping MBS v alues—and especially those MBS

ba cked by subprime and other r isky l oans—to fractions of their former prices. Mark-to-m arket accounting then

r equ ired financial institutions t o w rite down t he value of t heir assets—r educing their capital positions and causing

g r eat investor and creditor unease.” U.S. Fin. Crisis In quiry Com m’n, The Financial Cris is Inquiry Report: Final

Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financ ial and Economic Cris is in the United States, at

444–445 (Official Gov’t ed. 2011) (FCIC Report), available at https://www.gpo.gov /fdsy s/pkg/GPO-

FCIC/pdf/GPO-FCIC.pdf.

15

For example, such securities were used as collateral for borrowing. See id. a t 43.

16

T h e Housing and Econom ic Rec overy Act of 2008 (HERA), which created the Federal H ousing Financ e Agency

(FHFA), granted the Director of FHFA discretionary authority to a ppoint FHFA conservator or receiver of the

En terprises ‘‘for the purpose of r eorganizing, rehabilitating, or winding up the affairs of a regulated entity.’’ Housing

and Economic Recovery Act of 2008, section 1367 (a)(2), amending the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial

Safety a nd Soundness A ct of 1 992, 12 U.S.C. § 4 617(a)(2). On September 6, 2008, FHFA exercised that authority,

pla cing Fannie Ma e a nd Freddie Ma c into conservatorships. Fed. Hous. Fin. Agency, Conservator’s Report on the

Enterpris es’ Financial Performance, at 17 (2 nd Quarter 2012), available at

h t tps://www.fhfa.gov /webfiles/24549/ConservatorsReport2Q2012.pdf

.

17

FCIC Report, s upra note 14, at 156.

18

Fed. Reserve Sy stem, The U. S. Ho using Market: Current Conditions and Po licy Co nsiderations, at 3 ( Fed. Reserve

Bd., White Paper, 2012), available at https://www. federalreserve.gov/publications/other-reports/files/housing-

w h ite-paper-2 012 0104 .pdf.

19

See Lender Processing Servs., LPS Mortgage Monitor: May 2012 Mo rtgage Performance Observ ations, Data as of

April 2012 Month End, at slide 3, 11 (May 2012), available at

h ttp://www.bkfs.com /CorporateInformation/NewsRoom/MortgageMonitor/201204MortgageMon itor/MortgageM

on i t orApril2 012.pdf.

17 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

In response to the crisis, Congress passed the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act), which was signed into law on July 21, 2010.

20

In the Dodd-

Frank Act, Congress included a significant number of new provisions governing the origination

of consumer mortgages. In particular, sections 1411 and 1412 of the Dodd-Frank Act amended

the T ruth In Lending Act (TILA) by adding sections 129C(a) and (b).

21

These amendments to

T ILA generally provide that no creditor may make a residential mortgage loan unless the

creditor makes a reasonable and good faith determination based on verified and documented

information that, at the time the loan is consummated, the consumer has a reasonable ability to

repay the loan.

22

The amendments to TILA also establish a presumption of compliance with the

ability-to-repay requirement for creditors originating a category of loan called a “qualified

mortgage” (QM).

23

Congress directed the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (Bureau) to

issue rules to effectuate certain of these amendments

24

and authorized the Bureau to prescribe

regulations revising, adding to, or subtracting from the criteria that define a qualified

mortgage.

25

In January 2013, to implement sections 1411 and 1412 of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Bureau

published a final rule titled ‘‘Ability-to-Repay and Qualified Mortgage Standards Under the

Truth in Lending Act (Regulation Z)’’ (January 2013 Rule).

26

The Bureau amended the January

2013 Rule several times both before it took effect on January 10, 2014 and afterwards. For

purposes of determining whether the January 2013 Rule was significant under section 1022(d)

of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Bureau made its determination based on the January 2013 Rule and

amendments to it that took effect on January 10, 2014.

27

However, in order to facilitate a clearer

and more meaningful assessment, the assessment and this report take into consideration certain

20

Pu b. L. No. 111–203, 124 Stat. 1376 (2010).

21

T ILA section 1 29C(a)–(b) (c odified a s am ended at 1 5 U.S.C. § 1 639c(a)–(b)).

22

TILA section 129C(a) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C. § 1639c(a)).

23

T ILA section 1 29C(b) (c odified a s amended a t 15 U.S.C. § 1 639c(b) ).

24

Con gress g enerally c onsolidated i n the Bu reau the rulemaking authori ty for Federal consumer financial l aws

pr ev iously vested in certain other federal agencies. Congress a lso provided the Bureau wi th the authority t o, among

oth er things, prescribe rules as may be necessary or appropriate to enable the Bureau to administer and carry out

t h e purposes and objectives of t he Federal consumer financial l aws and to prevent ev asions thereof. 1 2 U. S.C. §

5 5 12(b)(1). The Federal consumer financial laws include TILA.

25

TILA section 1 29C(b)(3)(B)(i) (codified a s amended a t 15 U.S.C. § 1639c(b)(3)(B)(i)).

26

7 8 Fed. Reg. 6408 (Jan. 30, 2013).

27

See Section 1 .1.2, at n. [41].

18 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

amendments affecting small creditors that took effect in 2016.

28

Therefore, the term “ATR/QM

Rule” (or “Rule”) generally refers throughout this report to ability-to-repay and qualified

mortgage requirements in effect as of January 2014; except that for certain analyses of small

creditors, the Rule includes requirements on small creditors in effect as of March 2016, as

indicated.

The ATR/QM Rule, among other things, describes certain minimum requirements for creditors

making ability-to-repay determinations, but does not dictate that they follow particular

underwriting standards. Creditors generally must consider certain specified underwriting

factors and use reasonably reliable third-party records to verify the information on which they

rely to determine repayment ability.

29

The ATR/QM Rule also defines several categories of QM

loans for which, as noted above, compliance with the ATR requirement is presumed.

30

The

presumption of compliance can be either conclusive (e.g., a safe harbor) for QM loans that are

not ‘‘higher-priced’’, or rebuttable, for QM loans that are ‘‘higher-priced.’’

31

Section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Bureau to conduct an assessment of each

significant rule or order adopted by the Bureau under Federal consumer financial law.

32

As

discussed further below, the Bureau has determined that, for purposes of section 1022(d), the

January 2013 Rule and amendments to it that took effect on January 10, 2014 is a significant

rule. Another requirement of section 1022(d) is that the Bureau publish a report of the

assessment within five years of the effective date of the significant rule or order. This document

is the report of the Bureau’s assessment of the ATR/QM Rule in accordance with section

1022(d).

In June 2017, the Bureau published a Request for Information (RFI) requesting public comment

on its plans for assessing the Rule, and requesting certain recommendations and information

28

See 80 Fed. Reg. 59943 (Oct. 2, 2015) (among other things, this rule increased the mortgage originations threshold

for sm all creditors and expanded t he definition of “ rural area.”) See als o 81 Fed. Reg. 1 6074 (Mar. 25, 2016) ( this

r u le remov ed “predom inantly” as a qualifier of t he “operates in rural or underserved areas” r equirement).

29

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(c)(2)–(4). The eight factors that must be considered in an ATR determination are listed in

Section 2.3.2, below.

30

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(e)–(f).

31

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(1). A “higher-priced covered transaction” is defined at 12 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(b)(4) as “a

cov ered transaction with a n annual percentage rate that exceeds the average prime offer rate for a com parable

transaction as of the date the interest rate is set by 1.5 or more percentage points for a first-lien cov ered transaction,

other than a qualified mortgage under paragraph (e)(5), (e)(6), or (f) of this section; by 3.5 or more percentage

poin ts for a first-lien c ov ered transaction that is a qualified m ortgage under paragraph (e)(5), (e)(6), or (f) of this

section; or by 3.5 or more percentage points for a subordinate-lien c ov ered transaction.”

32

1 2 U.S.C. § 5512(d).

19 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

useful in conducting the assessment.

33

The Bureau received approximately 480 comments in

response to the RFI. The Bureau considered data and other relevant information provided by

commenters, as well as comments on the assessment plan, as it conducted the assessment and

prepared this report.

34

This report does not generally consider the potential effectiveness of alternative requirements

on the origination of consumer mortgages that might have been or might be adopted, nor does it

include specific proposals by the Bureau to modify any rules. The Bureau expects that the

assessment findings made in this report and the public comments received in response to the

RFI will help inform the Bureau’s future policy decisions concerning consumer mortgages,

including whether to commence a rulemaking proceeding to make the ATR/QM Rule more

effective in protecting consumers, less burdensome to industry, or both. In future policy

development, the Bureau expects to consider other public comments, including comments

received in 2018 in response to a series of requests for information about Bureau activities.

35

Those comments are not summarized in this report.

Finally, the Bureau’s assessments pursuant to section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act are not

part of any formal or informal rulemaking proceedings under the Administrative Procedure Act.

This report does not represent legal interpretation, guidance, or advice of the Bureau and does

not itself establish any binding obligations. Only the rules and their official interpretations

(commentary) establish the definitive requirements.

1.1 Purpose and scope of the assessment

1.1.1 Statutory requirement for assessments

Section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act requires the Bureau to conduct an assessment of each

significant rule or order adopted by the Bureau under Federal consumer financial law.

36

The

33

Requ est for In formation Regarding Ability-to-Repay/Qualified Mor tgage Rule Assessm ent, 82 Fed. Reg. 25246

(Ju ne 1, 2017).

34

Sum maries of t he different types of com ments received in response to the RFI a re included in Appendix B t o t his

r eport. See also Section 1.2 below.

35

Requ est for In formation Regarding the Bu reau’s A dopted Regulations and New Rulemaking Authorities, 83 Fed.

Reg . 1 2286 (Mar. 21, 2018).

36

1 2 U.S.C. § 5512(d).

20 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Bureau must publish a report of the assessment not later than five years after the effective date

of such rule or order. The assessment must address, among other relevant factors, the rule’s

effectiveness in meeting the purposes and objectives of title X of the Dodd-Frank Act and the

specific goals stated by the Bureau.

37

The assessment must reflect available evidence and any

data that the Bureau reasonably may collect. Before publishing a report of its assessment, the

Bureau must invite public comment on recommendations for modifying, expanding, or

eliminating the significant rule or order.

The purposes and objectives of title X of the Dodd-Frank Act are set out in section 1021 of the

Dodd-Frank Act. Pursuant to section 1021(a) of the Dodd-Frank Act, the purpose of the Bureau

is to implement and, where applicable, enforce Federal consumer financial law consistently for

the purpose of ensuring that all consumers have access to markets for consumer financial

products and services and that markets for consumer financial products and services are fair,

transparent, and competitive.

38

The objectives of the Bureau are listed in section 1021(b) of the

Dodd-Frank Act. Specifically, section 1021(b) provides that the Bureau is authorized to exercise

its authorities under Federal consumer financial law for the purposes of ensuring that with

respect to consumer financial products and services:

39

1. Consumers are provided with timely and understandable information to make

responsible decisions about financial transactions;

2. Consumers are protected from unfair, deceptive, or abusive acts and practices and from

discrimination;

3. Outdated, unnecessary, or unduly burdensome regulations are regularly identified and

addressed in order to reduce unwarranted regulatory burdens;

4. Federal consumer financial law is enforced consistently, without regard to the status of a

person as a depository institution, in order to promote fair competition; and

5. Markets for consumer financial products and services operate transparently and

efficiently to facilitate access and innovation.

37

The specific goals of the ATR/QM Rule are discussed below in Section 1.1.3.

38

1 2 U.S.C. § 5511(a).

39

1 2 U.S.C. § 5511(b).

21 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

1.1.2 Overview of the ATR/QM Rule

T he Dodd-Frank Act amended T ILA to provide that no creditor may make a residential

mortgage loan unless the creditor makes a reasonable and good faith determination based on

verified and documented information that, at the time the loan is consummated, the consumer

has a reasonable ability to repay the loan. The amendments to TILA also establish a

presumption of compliance with the ability-to-repay requirement for creditors originating a

qualified mortgage.

As noted above, the Bureau first implemented these requirements in the January 2013 Rule.

40

The Bureau amended the January 2013 Rule several times both before it took effect on January

10, 2014, and afterwards. For purposes of determining whether the January 2013 Rule was

significant under section 1022(d) of the Dodd-Frank Act, the Bureau made its determination

based on the January 2013 Rule and amendments to it that took effect on January 10, 2014.

41

However, in order to facilitate a clearer and more meaningful assessment, the assessment and

this report take into consideration certain amendments that took effect in 2016. These

amendments revised the definition of a small creditor and preserved the ability of small

creditors to make balloon-payment QMs without regard to whether they operated

predominantly in rural or underserved areas.

42

Therefore, as stated above, the term “ATR/QM

40

See 78 Fed. Reg. 6408 (Jan. 30, 2013). The January 2013 Ru le a lso included: (i) special prov isions for creditors

refinancing “non-standard mortgages;” (ii) certain limits on prepayment penalties; (iii) enhanced record retention

requirements; and (iv) anti-evasion provisions. T his Report does n ot discuss these prov isions at length given t heir

m odest im pact on the ov erall effectiveness of t he ATR/Q M rule in m eeting the purposes and obj ectives of t itle x and

t h e goals specified by t he Bureau in the rule. For example, the special prov isions for refinancing “non-standard

m ortgages” prov ide an exception to the ATR r equirement, but a s Chapter 4 points out, these types of loans, (i.e.,

in t erest-only, negative amortization, or A RMs w ith an introductory period of on e year or longer), are quite rare in

the post-Rule period and already made up a sm all share of t he m arket in the years im mediately prior t o the Rule’s

effec tive date. The prepayment penalty and recordkeeping p rovisions are additional standards and requirements

based on other Dodd-Frank Act provisions (sections 1414 and 1416, respectively) not directly r elated to the ATR

det ermination. No c om ments that w ere r eceived on the assessm ent focused on any of t hese prov isions and the

Bu r eau has marshaled its resources to examine prov isions more central to t he ATR determination and the

effec tiveness of t he A TR/QM Ru le.

41

Wh en the January 2013 Rule was issued, the Bureau concurrently issued a proposal to amend it, and that proposal

w a s finalized on May 29, 2013. See 78 Fed. Reg. 6622 (Jan. 30, 2013) (January 2013 ATR Proposal) ; 78 Fed. Reg.

3 5 430 ( June 12, 2 013) ( May 2013 A TR Rule). The Bureau issued additional corrections and clarifications in the

su mmer and fall of 2 013. See 7 8 Fed. Reg. 44686 (July 24, 2013); 7 8 Fed. Reg. 60382 (Oct. 1 , 2013); 7 8 Fed. Reg.

62993 (Oct. 23, 2 013). Am endments that took effect a fter January 1 0, 2014, are an i nterpretive rule regarding

su ccessors-in-i n ter e st, see 79 Fed. Reg. 41631 (July 17, 2014); a rule related t o nonprofit entities and which also

pr ov ided a cure m echanism for the points and fees limit that a pplies to qualified mortgages, s ee 7 9 Fed. Reg. 65300

(Nov . 3, 2014); r evisions to the definitions of sm all c reditor and rural area, s ee 80 Fed. Reg. 59943 (Oct. 2, 2015); a

procedural rule establishing an application process for designation as a rural area, see 81 Fed. Reg. 11099 (March 3,

2 01 6); and revisions t o the r equirements for QM loans issued by sm all creditors, see 81 Fed. Reg. 16074 (March 25,

2 01 6) .

42

See 8 0 Fed. Reg. 59943 (Oct. 2, 2 015) (revisions to the definitions of sm all c reditor and rural area); 81 Fed. Reg.

1 6074 (Mar. 25, 2016) (revisions to the requirements for QM loans issued by small creditors).

22 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

Rule” (or Rule) generally refers throughout this report to ability-to-repay and qualified

mortgage requirements in effect as of January 2014, except for certain analyses of small

creditors, as indicated.

As discussed in greater detail in Chapter 2, the ATR/QM Rule describes certain minimum

requirements for creditors making ability-to-repay determinations. Creditors generally must

consider certain minimum underwriting factors and they generally must use reasonably reliable

third-party records to verify the information they use to determine repayment ability.

43

The

Dodd-Frank Act attached civil liability to a creditor’s failure to meet the ability-to-repay

requirement.

T he Dodd-Frank Act also established a presumption of compliance with the ability-to-repay

requirement and protection from liability for creditors originating a qualified mortgage. The

Rule defines several categories of qualified mortgages. All categories must meet certain

requirements, which include having terms of 30 years or less, regular periodic payments that are

substantially equal (except in the case of adjustable-rate or step-rate mortgages) that do not

result in the increase of the principal balance, and total points and fees which do not exceed a

certain percentage of the loan amount.

44

Additional restrictions apply depending on the type of

qualified mortgage.

45

One category of qualified mortgage is the “General QM.” To fall within this category, the ratio of

the consumer’s total monthly debt payment to total monthly income (DTI) cannot exceed 43

percent and must be calculated using debt and income in accordance with Appendix Q.

46

The

criteria for General QM further require that creditors calculate mortgage payments based on the

highest payment that will apply in the first five years of the loan.

47

This category also includes a

restriction on balloon payment features.

A second category of qualified mortgage is the “Temporary GSE QM.” T his is a separate,

temporary category of QM for loans eligible to be purchased or guaranteed by either Fannie Mae

or Freddie Mac (collectively, the Government Sponsored Entities or GSEs) while they operate

under federal conservatorship or receivership. Under the terms of the Rule, the Temporary GSE

43

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(c)(2)–(4).

44

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(2)(i)–(iii).

45

Ch apter 2 prov ides a full discussion of t he r equirements for qualified m ortgages. The summary below prov ides

in formation that may be especially useful for understanding the empirical analyses in subsequent chapters.

46

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(2)(vi).

47

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(2)(iv).

23 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

QM category will continue to be in effect until the earlier of: (i) the end of conservatorship; or

(ii) January 10, 2021.

48

The Rule also provided a temporary QM category for loans eligible to be insured by the U.S.

Department of Housing and Urban Development (FHA Loans); guaranteed by the U.S

Department of Veterans Affairs (VA Loans); guaranteed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture

(USDA Loans); or insured by the Rural Housing Service (RHS Loans) (collectively, ‘Temporary

Federal Agency QM’).

49

The category of Temporary Federal Agency QM no longer exists and has

been replaced by the category of Federal Agency QM because the relevant federal agencies (i.e.,

FHA, VA, and RHS) have all now issued their own qualified mortgage rules.

50

The Bureau is not

considering these Federal Agency QM rules in the assessment, which is limited to the Bureau’s

own ATR/QM Rule.

A fourth category of qualified mortgages provides more flexible underwriting standards for

small creditor portfolio loans,

51

and a fifth category allows small creditors that operate in rural

or underserved areas to make balloon-payment portfolio loans that are qualified mortgages.

52

A

temporary category that expired in April 2016 allowed any small creditor to make balloon-

payment portfolio loans that are qualified mortgages, even if they did not operate in rural or

underserved areas.

53

However, amendments prior to the expiration revised the “operate in rural

areas” requirement and preserved the ability of small creditors to make balloon-payment QMs

without regard to whether they operated “predominantly” in rural or underserved areas so long

as such creditors make at least one residential mortgage in a rural or underserved area.

54

1.1.3 Goals and expected effects of the Rule

The goals of the ATR/QM Rule generally reflect the specific goals set forth by Congress in the

relevant amendments to TILA. Specifically, TILA section 129B, added by section 1402 of the

Dodd-Frank Act, states that Congress created new TILA section 129C upon a finding that

48

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(4)(ii)(A).

49

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(4)(ii)(B)–(E).

50

See, e.g., 24 C.F.R. § 2 03.19 (for HUD rules).

51

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(5).

52

1 2 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(f).

53

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.43(e)(5).

54

1 2 C .F.R. § 1 026.35(b)(2)(iii)(A); s ee also supra note 42.

24 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

“economic stabilization would be enhanced by the protection, limitation, and regulation of the

terms of residential mortgage credit and the practices related to such credit, while ensuring that

responsible, affordable mortgage credit remains available to consumers.”

55

T ILA sec tion 129B

further states that the purpose of TILA section 129C is to “assure that consumers are offered and

receive residential mortgage loans on terms that reasonably reflect their ability to repay the

loans and that are understandable and not unfair, deceptive or abusive.”

56

In its January 2013 Rule implementing these TILA amendments, the Bureau recognized that a

goal of the statute was to prevent a repeat of the deterioration of lending standards which

preceded the financial crisis and which led to various consumer harms.

57

For example, the

Bureau noted that the ATR requirement of the Rule was intended to prevent consumers from

obtaining mortgages they could not afford.

58

To the extent that the January 2013 Rule would

reduce credit access, the goal was to reduce lending that ignored or inappropriately discounted a

consumer’s ability to repay.

59

The Bureau viewed these effects as consistent with congressional

intent and one of the benefits of the Rule.

60

Similarly, by requiring that creditors determine

ability to repay based on an amortizing payment using the fully indexed rate

61

(or the maximum

possible rate in five years for certain categories of qualified mortgages), the statute

62

and the

Rule effectively prohibited underwriting loans based upon low initial monthly payments.

63

Non-

55

TILA section 1 29B(a)(1) (codified as amended at 15 U.S.C . § 1639b(a)(1)).

56

T ILA section 1 29B(a)(2) (codified as am ended at 1 5 U.S.C. § 1639b(a)(2)).

57

See 78 Fed. Reg. 6408, 6570 (Jan. 3 0, 2013)(“A primary goal of t he statute was to prevent a r epeat of the

deterioration of lending standards that contributed to the financial crisis, which harmed consumers in v arious ways

a n d significantly c urtailed their access t o c redit.”).

58

“The statutory ability-to-repay standards reflect Congress’s belief that certain lending practices (such as low- or no-

documentation loans or underwriting loans without regard to principal repayment) led to consumers having

m ortgages they could not a fford, r esulting i n high default and foreclosure rates.” Id. a t 6415.

59

“ The Bureau believes that, t o the extent the final rule r educes c redit access, it will primarily reduce ineffic ient

len ding t hat ignores or inappropriately discounts a consumer’s ability to r epay the loan, thereby preventing

consumer harm, rather than impeding a ccess t o credit for borrowers that do have an ability to r epay.” Id. at 6570.

See also id. at 6558–6560 (Econom ics of A bility T o Repay).

60

See, supra note, 58.

61

“ Fu lly indexed rate” means the interest rate calculated u sing the index or formula that will apply after recast, a s

determined at the tim e of consummation, and the maxim um margin that can apply at any time during the loan term.

See 12 C.F.R. § 1 026.43(b)(3).

62

T ILA section 1 29C(a)(6)(D)(iii) (c odified a s am ended at 15 U.S.C. § 1 639c(a)(6)(D)(iii))(prov iding “the interest rate

ov er the entire t erm of the loan is a fixed rate equal to t he fully indexed rate a t the t ime of t he loan closing, w ithout

considering the introductory rate.”).

63

For example, low initial payments may occur as the interest-only payments on interest-only loans or negatively

am ortizing option ARMs or result from the introductory rates on hybrid ARMs. The statute required on ly the use of

25 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

amortizing products were expected likely to persist only in narrow niches for more sophisticated

borrowers who wanted to match their mortgage payment to changes in their expected income

stream, and who had the resources to qualify for the products under the underwriting

assumptions the statute and regulation required.

64

The Bureau stated a number of other general and particular goals in the January 2013 Rule. The

Bureau stated that it sought to allow for flexible proprietary underwriting standards in ability-

to-repay determinations and to support innovation.

65

The Bureau also sought to provide

qualified mortgage standards that would allow creditors and the secondary market to readily

determine whether a particular loan is a QM loan. For General QM loans, the ATR/QM Rule

generally requires creditors to use the standards for defining “debt” and “income” in Appendix

Q, which were adapted from FHA guidelines. The Bureau expected that the standards set forth

in Appendix Q, together with the bright-line 43 percent threshold, would provide sufficient

detail and clarity to encourage creditors to provide qualified mortgages to consumers.

66

The

Bureau also noted, however, that the Rule might have an adverse effect on access to credit for

consumers with atypical financial characteristics, such as income streams that are inconsistent

over time or particularly difficult to document.

67

The Bureau stated a number of goals for the categories of temporary QM loans.

68

The Bureau

sought to preserve access to credit for consumers with debt-to-income ratios above 43 percent

during a transition period in which the market was fragile and the mortgage industry was

the fully indexed rate. The Rule requires use of the fully indexed rate or initial rate, whichever i s greater (1 2 C.F.R. §

1 026.43(c)(5)(i)(A)).

64

See 78 Fed. Reg. 6408, 6562 (Jan. 30, 2013).

65

Id. a t 6 461 (“The Bureau believes that a variety of underwriting standards c an y ield reasonable, good faith a bility-

to-r epay determinations…. [C]reditors are permitted to dev elop and a pply their own proprietary underwriting

standards and to make changes to those standards over time in response to empirical information and changing

econ om ic and other conditions. T he Bureau believes this fl exibility is necessary given the w ide range of c reditors,

con sumers, and m ortgage products to which this rule appli es.”). Further, “In crafting t he rules t o im plement the

qu a lified mortgage prov ision, the Bureau has sought to b alanc e creating new protecti ons for consumers and n ew

r esponsib ilities for creditors with preserving c onsumers’ a ccess t o credit and allow ing for appropriate lending and

innovation.” Id. at 6505.

66

“ [T ]he Bureau r ecognizes c oncerns that c reditors should readily be able t o determine w hether indivi dual m ortgage

t r ansacti ons will be deemed qualified mortgages. T he Bureau addresses these c oncerns by adopting a bright-line

debt-to-incom e ratio threshold of 43 percent, as w ell as clear and specific standards, based on FHA guidelines, set

for t h in a ppendix Q for calculating the debt-to-income ratio in i ndividual cases.” Id. at 6525. The 2011 multi-agency

Credit Risk Retention Proposed Rule also r elied on FHA standards for defining “debt” and “ incom e” for purposes of

defining “qualified r esidential mortgage” (QRM) , which would b e exempt from the r isk retention r equirements. Id.

a t 6 5 27; s ee 76 Fed. Reg. 24090 (Apr. 29, 2011).

67

See 7 8 Fed. Reg. 6408, 6570 (Jan. 30, 2013).

68

See Chapter 6 for further discussion of the Temporary GSE QM category.

26 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

adjusting to the final rule.

69

By providing for most of the conventional market

70

to continue to

originate higher debt-to-income loans as QM loans, but limiting this to the conforming market

and making the provision temporary, the Bureau sought, over the long term, to encourage

innovation and responsible lending on an individual basis under the ability-to-repay criteria.

71

The Bureau expected that there would be a “robust and sizable market” for non-QM loans

beyond the 43 percent threshold and structured the Rule to try to ensure that this market would

develop.

72

The Bureau also stated that because the temporary category of QM loans covers loans

that are eligible to be purchased, guaranteed, or insured regardless of whether the loans are

actually purchased, guaranteed, or insured, private investors could acquire these loans and

secure the same legal protection as the GSEs and Federal agencies.

73

This would avoid creating a

disincentive for the return of private investors even before the expiration of the temporary

category.

Finally, the Bureau noted that as the market recovered, the GSEs and Federal agencies would be

able to reduce their presence in the market (e.g., by reducing their loan limits). In this scenario,

the percentage of loans granted qualified mortgage status under the temporary category would

69

7 8 Fed. Reg. 6408, 6533 (Jan. 30, 2013) (“[T]he Bureau acknowledges it may take some time for the non-qualified

m ortgage market t o establish itself in light of the market anxiety regarding litigation risk under the ability-to-repay

r u les, the g eneral slow recovery of the m ortgage market, and the need for lenders t o adjust their operations t o

account for several other major regulatory and c apital r egimes. In light of these factors, the Bureau has concluded

t h at it is appropriate t o prov ide a tem porary a lternative definition of qu alified m ortgage. This will help ensure

a cc ess t o responsible, affordable c redit is available for c onsumers with debt-to-incom e ratios a bov e 43 percent and

fa c ilitate com pliance by lenders by prom oting the use of widely recognized, federally-related underwriting

st a ndards”). On the t ight credit environment at the time of the rulemaking and the general reluctance of lenders

r egarding r isks, see id. a t 6412.

70

A conventi onal m ortgage l oan is on e that is not insured or guaranteed by the federal gov ernment, including the

Federal Housing Administration (FHA), the U.S. Department of V eterans A ffairs (VA), or the USDA’s Farm Service

A g ency or Rural H ousing Service (FSA/RHS). Conventional loans are either private or guaranteed by one of the two

G ov ernment Sponsored En terprises ( GS Es), the Federal National Mortgage Association (Fannie Ma e) and the

Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (Freddie Mac).

71

“[The final rule] allows room for a vibrant market for non-qualified m ortgages ov er t ime. The Bureau recognizes

th at there will be many instances in which individual consumers can afford an even higher debt-to-in com e r a tio

based on their particular circumstances, although the Bu reau believes that such loans are better evaluated on an

in dividual basis under t he ab ility-to-repay criteria rather than with a blanket presumption.” Id. at 6506.

72

“ Ov er the long term, as the market recovers from the mortgage crisis and adjusts to the ability-to-repay rules, the

Bu r eau expects that there will be a r obust and sizable m arket for prudent l oans beyond the 43 percent threshol d

ev en without the b enefit of t he presumption of com plianc e that applies to qu alified m ortgages. In short, the Bureau

does not believe that consumers who do not receive a qualified mortgage because of the 43 percent debt-to-in com e

ratio threshold should be cut off from responsible credit, and has structured the rule to try to ensure that a r obust

a n d affordable a bili ty t o-repay market develops ov er time.” Id. at 6528.

73

“ The t emporary exception has been c arefully structured t o cover loans that are eligible t o be purchased, guaranteed,

or in sured by the G SEs (while in conservatorship) or Federal agencies r egardl ess of whether the loans are actually

so purchased, guaranteed, or insured; this will leave room for private investors to return to the market and secure

t h e same l egal protection as the GS Es and Federal agencie s.” Id. at 6534.

27 BUREAU OF CONSUMER FINANCIAL PROTECTION

also shrink and the market would be able to develop alternative approaches to assessing ability-

to-repay within the General QM requirements.

74

When the January 2013 Rule was released, the Bureau issued public statements that reiterated

these goals and elaborated on particular aspects of these goals. The Bureau stated that

consumers would be protected from risky lending practices and would not receive loans that

they could not afford.

75

The Bureau also described “two distinctly different mortgage markets”

over the previous decade, the first in which lending was lax and a more recent one in which

credit was tight. The Bureau stated that its goal with the January 2013 Rule was to address both

of these issues, to make sure borrowers were assured of greater consumer protections and have

reasonable access to credit.

76

In May 2013, the Bureau amended the January 2013 Rule to exempt certain creditors and

mortgage loans from ability-to-repay requirements; provided an additional definition of a

qualified mortgage for certain loans made and held in portfolio by small creditors, and a

temporary definition of a qualified mortgage for balloon loans; and revised rules on how to

74

“ A t the same t ime, a s t he m arket r ecov ers and the GSEs and FHA are a ble to r educe their presence in the m arket,

t h e percentage of loans that are granted qualified m ortgage status under the t emporary definition will shrink

t ow ards the long term structure.” Id.

75