1

The Bench Memorandum

By Jessica Klarfeld

© 2011 The Writing Center at GULC. All rights reserved.

The bench memorandum is a document written by a law clerk for an appellate judge, which the

judge uses in preparing for oral arguments. A trial judge may ask his clerk to write a bench

memo in advance of a motions hearing; however, writing bench memos at the trial court level is

less common. Some of the Georgetown Legal Research and Writing faculty require law fellows

to write bench memos on the same topic on which their first-year students write their briefs.

When first-year students have oral arguments on their briefs, the student judges will use the law

fellows’ bench memos to familiarize themselves with the parties’ arguments.

The bench memo itself does NOT decide the case; it is not a brief by counsel or a judicial

opinion. Rather, the bench memo simply advises a judge by offering an objective review of both

sides of the case. As opposed to a brief, which explores only one side’s arguments (with brief

discussion of counterarguments), the bench memo summarizes and develops both sides’

arguments, recognizes the merits and drawbacks of those arguments, and recommends a course

of action.

1

When writing a bench memo, it is important to remember to focus on the best interests of justice.

The bench memo must help judges get past the advocacy of the parties’ briefs so that they can

reach independent decisions.

2

1

See MARY DUNNEWOLD, BETH A. HONETSCHLAGER & BRENDA L. TOFTE, JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: A PRACTICAL

GUIDE 126 (2010).

2

Id. (noting that the bench memo must clearly and accurately describe the facts of the case, the procedural posture,

the applicable law, the parties’ arguments, and the clerk’s independent analysis of the issue).

2

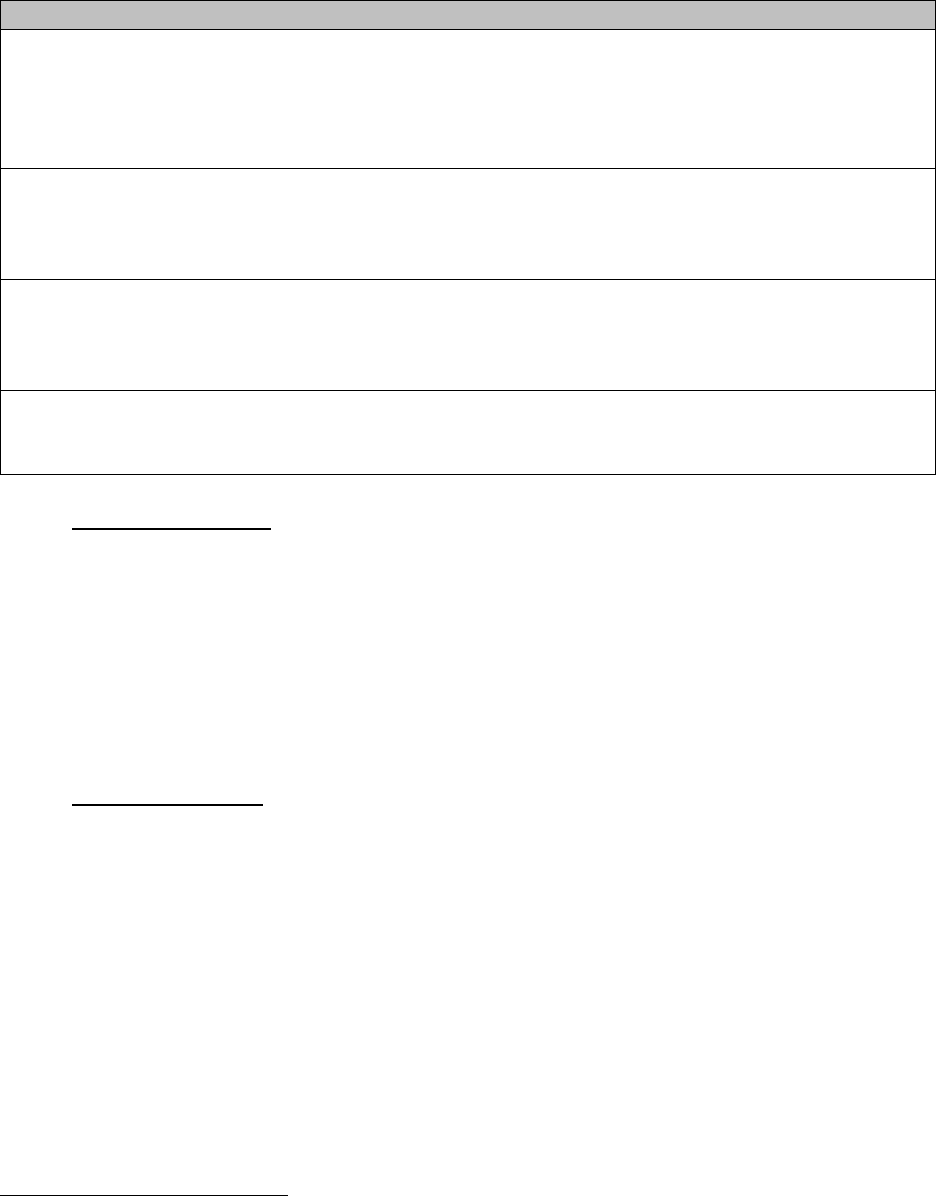

HOW BENCH MEMOS COMPARE TO MEMOS AND BRIEFS

3

MEMO

BENCH MEMO

BRIEF

PURPOSE

Memos discuss,

recommend, and

advise. The memo

objectively informs a

reader about what the

law is. It illustrates

what the outcome will

likely be when the law

is applied to a

particular set of facts.

Bench memos discuss,

recommend, and

advise. The bench

memo objectively

informs the reader

what the law is and

what the parties’

arguments are. It

illustrates what the

outcome should be

when the law is

applied to the facts of

the case.

Briefs argue. The

brief seeks to persuade

the reader that your

application of your

law to the facts is the

correct one. The goal

is to win the case,

using the law in the

most favorable way to

your client.

AUDIENCE

Another lawyer,

supervising attorney,

client.

Appellate judge,

district judge, judicial

clerk.

Opposing lawyer,

appellate judge,

judicial clerk, client.

STANCE

Objectivity in research

is necessary when

writing a memo. A

memo writer can then

use the outcome of that

research to present his

client’s case most

favorably. A memo

writer, however, is

clear about the

strengths and

weaknesses of his

client’s case.

Objectivity in research

is necessary when

writing a bench memo.

A bench memo writer

can use the outcome of

that research to

determine which

party’s arguments are

stronger. A bench

memo writer is clear

about the strengths and

weaknesses of each

party’s case.

Objectivity in research

is necessary when

writing a brief. A

brief writer strives to

use that research to

create legal arguments

and offer legal

conclusions that cast

his client’s case

favorably. A brief

writer emphasizes the

strengths, while

minimizing the

weaknesses, of his

client’s case.

LENGTH OF A BENCH MEMO

Unfortunately, there is no magic number of pages that your bench memo should be. The length

of a bench memo can greatly vary. Some bench memos are single issue memos, in which a

judge may request that you write a short memo on an individual issue that attorneys have not

explained adequately. This single issue memo may be as short as two or three pages. More

typically, though, as a judicial clerk or law fellow, you will write longer full-case memos, which

could even be fifty pages if there are comprehensive facts and multiple issues that the court

needs to decide.

3

See The Writing Center, Georgetown University Law Center, From Memo to Brief (2004) (comparing memos and

briefs). https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/From-Memo-to-Appellate-Brief.pdf

3

AUDIENCE OF A BENCH MEMO

The process of writing a bench memo is fairly uniform among courts; however, it is important

that you clarify the expectations of your judge (or professor, if writing the bench memo as a law

fellow) before starting to write. Knowing your audience is the first step in successful bench

memo writing, and you must always do as the judge requests.

4

Also, while stylistic and

structural preferences of the judge are important, knowing your audience also requires knowing

to what use your judge will put your writing.

5

Some judges use the bench memo early in the

process to help them develop an overall picture of the case; others read the bench memo last,

once the facts and arguments are clear in their mind.

6

It is also important to note that in appellate

courts, the bench memo will likely be read by every member of the panel (typically three judges

in intermediate appellate courts and the full court in state supreme courts), not just the clerk’s

own judge.

7

STRUCTURE OF A BENCH MEMO FOR AN APPELLATE COURT

A standard, full-case bench memo for an appellate court usually consists of the following parts:

(I) Issues on Appeal, (II) Procedural Posture, (III) Statement of Facts, (IV) Standard of Review,

(V) Analysis, and (VI) Recommendations.

I. Issues on Appeal

The issues should be framed such that the judge understands exactly what needs to be decided.

An effective issue statement includes:

(1) A reference to the relevant law

(2) The legal question

(3) Any legally significant facts

In mentioning the legally significant facts, it is important that you maintain objectivity,

addressing facts that are favorable to one side (and thus unfavorable to the other) and vice versa.

The issues on appeal are often framed in terms of whether the district court (i.e., trial court)

correctly/incorrectly (properly/improperly, etc.) did x. In framing it as “correctly,” one could

assume that the result you ultimately will reach is that whatever the district court did was proper.

Similarly, in framing it as “incorrectly,” one could assume that the result you ultimately will

reach is that whatever the district court did was improper. This is a safe assumption, and given

that you ultimately will provide a recommendation in the bench memo, it is appropriate to frame

the issues as such. Issues can also be framed in terms of the standard of review (e.g., “Did the

trial court abuse its discretion when . . . ?”).

4

FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER, LAW CLERK HANDBOOK: A HANDBOOK FOR LAW CLERKS TO FEDERAL JUDGES

(Sylvan A. Sobel, ed., 2d ed. 2007).

5

See The Writing Center, Georgetown University Law Center, In Chambers: Effective Writing Tips for Judicial

Interns and Law Clerks (2005).

https://www.law.georgetown.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/07/In-Chambers-

Effective-Writing-Tips-for-the-Judicial-Interns-and-Law-Clerks.pdf

6

DUNNEWOLD, HONETSCHLAGER & TOFTE, supra note 2, at 127.

7

Id. at 126-27.

4

5

EXAMPLES OF ISSUES ON APPEAL

Under Chimel v. California, did the District Court incorrectly suppress a can of lye that an

officer found in a cabinet in the hallway of Defendant’s house approximately ten minutes after

Defendant’s arrest when the cabinet was an unobstructed twelve feet from Defendant, the

officers lacked full control over Defendant, and Defendant was handcuffed in the back but had

a history of violence?

Did the District Court correctly determine that the speech regulated under New Columbia’s

statute prohibiting video game retailers from selling sexually violent video games to minors

constituted variable obscenity under Ginsberg v. New York, thus removing it from First

Amendment protection?

Under Iowa Code Section 99.99.99, did the District Court properly award custody to the

child’s mother when the mother has been their main care provider and has never been known

to physically punish her child, but she has a history of alcohol abuse and has been overheard

shouting at other adults?

8

Under the Sixth Amendment, did the trial court abuse its discretion and violate Mr. Robinson’s

right to a fair trial when, after the sheriff received a note indicating that someone would help

Mr. Robinson escape from custody, it required him to wear a leg restraint during trial?

9

II. Procedural Posture

The procedural posture is a summary of how the case arrived in the court. You should write the

procedural posture in a neutral manner. This section should describe what procedural steps led

to the particular issue (in a trial court) or what happened in the court below (in an appellate

court). For an appellate court, the procedural posture should note all important procedural facts

(e.g., the trial court’s conclusions of fact and law, any significant motions’ hearings, whether the

court granted/denied any motions, etc.), and it should include specific dates so that the judge can

understand the case chronologically.

III. Statement of Facts

The Statement of Facts is an objective description of both the background and the legally

significant facts. In drafting the Statement of Facts, you should review the relevant sections of

the record or transcript and all supporting documents. For a trial court bench memo, sources of

facts can include documents in the trial court file, exhibits, transcripts from previous hearings,

and your own notes. For an appellate court bench memo, facts will primarily be from the record,

the parties’ briefs, and any appendices to the briefs. You will need to confirm, though, that the

facts in the briefs and appendices are consistent with the record. If they are not, you should point

out these inconsistencies in the bench memo.

10

Only those facts that are necessary in understanding the context and that are relevant to the issues

before the court should be included in the Statement of Facts. If you draft the Statement of Facts

before writing the Discussion section, it is probably a good idea to be overly-inclusive. You can

8

MARY BARNARD RAY & JILL J. RAMSFIELD, LEGAL WRITING: GETTING IT RIGHT AND GETTING IT WRITTEN 205

(5th ed. 2010).

9

DUNNEWOLD, HONETSCHLAGER & TOFTE, supra note 2, at 141.

10

DUNNEWOLD, HONETSCHLAGER & TOFTE, supra note 2, at 135.

6

always delete any irrelevant facts in the revising and editing process. If you draft the Statement

of Facts after writing the discussion section, however, you can better tailor the facts to what facts

you use in outlining the parties’ arguments.

IV. Standard of Review

The standard of review is the standard by which appellate courts measure errors made by trial

courts on specific legal issues. The standard of review differs for each legal issue, and therefore,

you must research that specific subject matter in order to determine what standard of review

applies. It is crucial in determining how much leeway the court has in reviewing the trial court’s

decision. The common levels of standard of review from most restrictive to least restrictive are:

(1) arbitrary and capricious; (2) gross abuse of discretion; (3) abuse of discretion; (4) clearly

erroneous; and (5) de novo.

The standard review can be determinative of the case, and therefore, you must understand what

standard applies and then use that standard to frame your analysis.

You can place the standard of review either as a separate section immediately preceding the

discussion section or as the first sub-section in the discussion section.

V. Analysis

The analysis section is the core of the bench memo. Although you will be able to read both

sides’ briefs, the bench memo will often require you to conduct independent research as well.

You will need to both verify the legitimacy of the parties’ positions and search for any further

authority that is not cited by either party. You may hope that each party would cite to all

relevant statutory law, case law, etc. in their briefs; however, never assume that this is the case!

Further, never trust the attorneys’ reasoning alone; it is your job to check each attorney’s

reasoning and measure it against both your own objective view and the reasoning of the other

attorney. Basically, you will ALWAYS want to conduct your own research, both to catch non-

cited authority and to check the validity of the arguments.

In writing the discussion section of a bench memo, you will want to synthesize rules, engage in

analogical reasoning, address counterarguments, and eventually reach conclusions on which

party has the stronger argument on a given element or factor.

EXAMPLE OF ANALYSIS FOR A GIVEN ELEMENT/FACTOR

RULE

Even if the government shows a compelling state interest, to survive strict

scrutiny, a content-based regulation must be the most narrowly tailored

means to achieving that interest.

7

APPELLANT’S

ARGUMENT

New Columbia will argue that its statute is the most narrowly tailored

because it is not overly broad, and any less restrictive alternatives would

not be as effective in achieving its compelling state interest.

- The statute is not overly broad because it does not regulate the sale

of sexually violent video games to adults. . . .

- Simply allowing the ESRB to self-police violent video game

distribution would not adequately prevent minors from obtaining

the games. . . .

APPELLEE’S

ARGUMENT

Video Gamers Alliance will argue that the restriction is overly broad and

that there are less restrictive means by which New Columbia can advance

its compelling state interest.

- The statute is overly broad because it chills the sales of violence-

depicting video games that are actually protected by the First

Amendment. . . .

- Less restrictive means would achieve New Columbia’s interest of

protecting against exposure of minors to video games featuring

graphic sexual violence. . . .

The parties may use different cases in making their arguments. However, they may also use the

same case—one party may analogize the facts of the precedent case to the facts in its case, and

the other may try to distinguish the facts of the precedent case from facts in its case.

EXAMPLE OF BOTH PARTIES RELYING ON SAME CASE

RULE

Unexplained noises from inside the house during an arrest weigh in favor

of an officer’s reasonable articulable suspicion that the area harbors

dangerous third parties.

PRECEDENT

CASE

DISCUSSION

In Virgil, when officers went to the defendant’s residence to arrest him,

before the defendant opened the front door, the officers standing near the

rear of the house heard sounds coming from inside the rear of the

residence and alerted the officers at the front door. The officers, thus, had

a reasonable articulable suspicion that a third party could be at the

residence.

APPELLANT’S

ARGUMENT

The State will argue that similar to Virgil, in which the officers heard

sounds coming from inside the rear of the residence before the defendant

answered the door, Officers Bird and Dent heard footsteps and a thud

before Defendant opened the door, making them suspicious that there

were other individuals in the house.

APPELLEE’S

ARGUMENT

The defense, though, will attempt to distinguish Virgil from Defendant’s

case. Unlike in Virgil, in which the sounds the officers heard in the rear

of the house could not have been made by the defendant approaching the

door, in the present case, the sounds heard by the officers could have been

consistent with Defendant walking to the door.

8

CONCLUSION

Overall, the sounds from inside Durden’s house were fairly consistent

with Durden answering the door, since the officers heard them as they

waited at the front door. Therefore, the thud and footsteps do not weigh

in favor of a finding of reasonable articulable suspicion.

11

Like a brief, you will want to include point headings in your bench memo to guide the reader

through the parties’ arguments. The point headings will include both the relevant legal issue for

that given element or factor and any significant facts. Unlike a brief, though, your point

headings will not be persuasive concise arguments for your side. They will be more objective

questions or statements that address the relevant issues without favoring one side over the other.

EXAMPLES OF POINT HEADINGS

Was Officer Dent’s Search of the Ottoman Within the Cursory Visible Inspection of Places in

Which a Person Might Be Hiding?

Was Officer Dent’s Quick Search of the Cabinet “Incident to Arrest” When It Occurred

Approximately Ten Minutes After Dent Initially Searched Defendant and the Entryway?

Whether the Material Regulated by the Act Fits Within the Definition of Variable Obscenity

Under Ginsberg

Whether New Columbia has a Compelling Interest in Regulating Children’s Exposure to

Violent Video Game Content

VI. Recommendations

The Recommendations section consists of your conclusions and advice on how you think the

case should be decided and why. If the case is too close to call, you should note this. Again, you

are not deciding the case, but in reading both sides’ briefs, conducting extensive research, and

analyzing all of the arguments, you should be able to provide the judge with a reasoned

recommendation. You may also include recommendations throughout the Discussion section on

how you think each individual element or factor may/should come out, but the recommendations

in the Conclusion section will likely focus on the results on a larger scale (i.e., what the appellate

court should do regarding the district court’s holding).

EXAMPLE OF RECOMMENDATIONS

The issue before the Court is whether the District Court erred in granting the Motion to

Suppress of the can of lye. The can of lye was found in the cabinet of the hallway of Durden’s

house during a lawful search incident to arrest. The search of the cabinet was substantially

contemporaneous to the arrest, and the cabinet itself was in Durden’s immediate control. In

considering the totality of the circumstances, although Durden was handcuffed in the back and

was not threatening at the time of arrest, his history of violence and membership in a fight

club, the lack of control of the officers, and the short unobstructed path between Durden and

the cabinet all weigh in favor of the fact that the cabinet was in Durden’s immediate control.

Thus, the District Court incorrectly suppressed the can of lye, and this Court should reverse

the District Court’s decision to suppress the evidence.

11

Note that in the actual bench memo, another case was discussed as well, and the combination of the discussion

from these two cases resulted in the ultimate conclusion.

9

I respectfully recommend that the Court affirm Mr. Robinson’s conviction for first-degree

burglary because there was a need for the restraint, and the leg restraint was the least

restrictive alternative under the circumstances. Therefore, the use of the leg restraint during

Mr. Robinson’s trial did not violate his right to a fair trial.

USING A BENCH MEMO AS A WRITING SAMPLE

A bench memo can make a great writing sample! Just make sure that if you use a bench memo

that you write for a judge, you redact all party names and sensitive, identifying information.

Also, check with the judge to make sure that he/she is okay with you using what you wrote as a

writing sample and if there is any further information that needs to be redacted. You will not

have this problem with a bench memo you write as a law fellow since the facts, parties, and

issues are all developed by the professor. Lastly, if your bench memo is very long, chances are

an employer will not want to read all of it. Select the best part(s) to submit, and on your writing

sample cover page, you can include a short paragraph describing what you have omitted for

length considerations.

FOR FURTHER REFERENCE

CALVERT G. CHIPCHASE, FEDERAL DISTRICT COURT LAW CLERK HANDBOOK (2007).

REBECCA A. COCHRAN, JUDICIAL EXTERNSHIPS: THE CLINIC INSIDE THE COURTHOUSE (2d ed.

1999).

MARY L. DUNNEWOLD, BETH A. HONETSCHLAGER & BRENDA L. TOFTE, JUDICIAL CLERKSHIPS: A

PRACTICAL GUIDE (2010).

FEDERAL JUDICIAL CENTER, LAW CLERK HANDBOOK: A HANDBOOK FOR LAW CLERKS TO

FEDERAL JUDGES (Sylvan A. Sobel, ed., 2d ed. 2007).

JOSEPH L. LEMON, FEDERAL APPELLATE COURT LAW CLERK HANDBOOK (2007).