Homesharing for renters:

Barriers and opportunities

An LSE London report

commissioned by Airbnb

March 2024

Kath Scanlon and Ellie Benton,

with Christine Whitehead

With contributions from

Sónia Alves

Alda Botelho Azevedo

Montserrat Pareja-Eastaway

Michael Voigtlaender

Bernard Vorms

Foreword

The cost-of-living crisis across the UK has been felt by everyone. In some areas, rents are at some of

the highest rates on record, and inflation continues to drive up prices. These challenges have left

many looking for additional ways to make ends meet, including through participating in the sharing

economy.

Airbnb was born in 2007 during an economic crisis when our founders couldn't afford to cover an

increase in their rent. Since then, hosting on Airbnb has become an economic lifeline to many people

and, according to our own research, more than a third of Hosts across the UK now say they offer

their place as a short-term let in order to afford the rising cost of living. Yet many renters cannot

access the same opportunity. This new research from the London School of Economics, supported by

Airbnb, looks for the first time at the possible benefits of, and obstacles to, homesharing within the

private rented sector, as well as highlighting the potential for reforms.

We investigated this area in order to look at the financial and social advantages of homesharing,

which are typically closed off from the large renter population in our society. This report sheds light

on the barriers that many renters face in participating in homesharing, such as legal and contractual

restrictions. It also identifies practical ways to give greater freedoms and economic opportunities to

renters in the places they call home. The study acknowledges the relationship between renters and

landlords, highlights positive cases where agreed homesharing can deliver a mutual benefit, and

describes legislative and contractual changes to make this possible.

This research is not only about gathering data; it's about understanding people's lives, how people in

the UK choose to live, and where spare space could be used to generate greater financial security.

It's also about starting a conversation that could lead to change, and ultimately helping more people

unlock additional income to afford the places they call home.

Evaluating the challenges to renters is one part of the broader housing debate in the UK, where the

role of short-term lets is also under discussion. We firmly believe that short-term lets in the UK

should be regulated and we have long called for the introduction of nationwide rules that work for

everyone. Rules for short-term lets need to strike a balance that protects tourism, ensures everyday

British people can still earn additional income from sharing their homes, and gives local authorities

the tools they need to understand and address demonstrated housing concerns in their

communities.

We hope this research can spark a new conversation about the ideal design of a modern housing

sector and the ways in which Airbnb can support renters and landlords in benefitting from

homesharing.

Amanda Cupples

General Manager for Northern Europe

1

Table of contents

Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. 2

Definitions ............................................................................................................................................ 2

Acronyms ............................................................................................................................................. 2

Executive summary ...................................................................................................................... 3

Recommendations ............................................................................................................................... 4

1 Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 6

Research questions and methods ........................................................................................................ 6

2 Existing studies of short-term lets .............................................................................................. 8

3 UK spare room hosts on Airbnb: tenure and earnings ............................................................... 10

Tenure of hosts ..................................................................................................................................10

Earnings from spare room lets ...........................................................................................................11

4 Hosts’ motivations for renting out spare rooms ....................................................................... 15

Lodgers vs Airbnb guests ...................................................................................................................16

Former hosts ......................................................................................................................................16

5 UK regulatory, legal and contractual context ............................................................................ 17

Existing STL regulation in England and Wales ...................................................................................17

Future regulation in England & Wales: Renters (Reform) Bill and new STL rules .............................17

STL regulation in Scotland..................................................................................................................18

Subletting, lodgers and tenancy agreements ....................................................................................18

Government’s model lease: private rented sector .........................................................................19

NHF model lease: Housing associations ........................................................................................19

Airbnb’s own insurance ......................................................................................................................20

Evidence about tenants and their leases ...........................................................................................20

6 Spare room letting in Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon and Paris.......................................................... 21

The four cities .....................................................................................................................................21

Policy debates ....................................................................................................................................22

Regulatory situation in each city .......................................................................................................22

Summarising the international picture ..............................................................................................25

7 Discussion and conclusions ...................................................................................................... 26

8 Recommendations .................................................................................................................. 27

References ................................................................................................................................. 28

Annex: The situation in four European cities ............................................................................... 30

Barcelona (Spain) ...............................................................................................................................30

Berlin (Germany) ................................................................................................................................32

Lisbon (Portugal) ................................................................................................................................33

Paris (France) .....................................................................................................................................35

2

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all the Airbnb spare room hosts who took part in the research. We learned a great

deal from everyone, especially focus group participants and interviewees. We are also grateful to the

international experts who contributed to our understanding of the situation elsewhere in Europe.

This is an independent report, commissioned by Airbnb. The analysis and conclusions are those of

the main authors and may not reflect the views of Airbnb or our international contributors.

Definitions

Terms have the following meanings in this report:

Whole homes: short-term lets of entire dwellings, where the host is not present. Whole

home listings may be

● Hosts’ own primary residences which are let out when the host is away

● Other dwellings used regularly by the host (eg second homes)

● Dedicated short-term rentals.

The majority of hosts on Airbnb have a single listing

1

.

Spare rooms: short-term lets of individual rooms in homes that are otherwise occupied; the

host is usually but not always present. On the Airbnb platform these are known as

‘Private Rooms’.

Hosts: the people or firms responsible for Airbnb listings. Most of the hosts discussed in this

report are individuals letting out spare rooms or other spaces in their main homes.

Airbnb refers to them as Hosts (upper-case).

Tenants: Hosts who rent their homes from landlords—as opposed to home owners.

Because the subject of this report is short term lets by hosts who are themselves tenants, it is

important to distinguish between long- and short-term rentals. We have used the term ‘rent’ for

long-term rentals and ‘lets’ for short-term rentals of whole homes or of spare rooms, such as

through hosting on Airbnb or other booking platforms.

The definitions are those of the authors and may differ from Airbnb’s own terminology.

Acronyms

The following acronyms are used:

PRS: private rented sector

STLs: short-term lets

1

4 in 5 UK hosts have one listing on Airbnb: https://www.airbnb.co.uk/e/simpletruths

3

Executive summary

Peer-to-peer accommodation has grown in popularity in the past few decades and Airbnb, a popular

short-term let (STL) booking platform, has become a household name in the UK and many other

countries. It was originally founded to facilitate the letting of spare rooms rather than whole homes

and this has always been part of its offer: according to Airbnb, as of January 2023, 26.5% of active

listings were private rooms

2

. In recent years, the company has continued to launch specific initiatives

focused on private rooms, which Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky has described as “getting back to the

idea that started it all – back to [Airbnb’s] founding ethos of sharing.”

In the UK there are few restrictions on homeowners letting out their spare rooms, but tenants’

leases often prohibit the activity without the explicit consent of the landlord or even forbid it

completely. The cost of living crisis and the Renters (Reform) Bill provide the context for this

research, which looked at the contribution of earnings from spare room lets to household incomes

and the barriers to such lettings, especially for hosts who are themselves tenants.

The research involved a literature review, analysis of Airbnb data, a survey of 1500 UK spare room

hosts and a programme of focus groups and interviews. Most academic literature on STLs relates to

tourism and hospitality or to housing and focuses on STLs of whole homes, not spare rooms. We also

looked at policies around spare room lets in four European cities. Again, most policies relate to STLs

of whole homes although some jurisdictions do require licences for STLs of spare rooms.

In the UK, London has the most spare room listings both in absolute terms and relative to its

population; the South West and parts of Scotland also have high numbers. According to Airbnb data,

the average annual earnings of UK spare-room hosts was about £5000 in 2022

3

. The median was

lower, as the average was pulled up by earnings from listings in higher-cost areas. Up to £7500 can

be earned tax-free from STLs of spare rooms under the UK’s Rent a Room Scheme.

Earnings from letting out a spare room can boost incomes: on average, spare room lets made up

16% of our survey respondents’ household incomes

4

. In principle, tenants might benefit more than

homeowners from letting out spare rooms, as they tend to have lower incomes and spend a higher

proportion on housing--although rented homes are on average smaller and less likely to have

unoccupied rooms. But although 37% of English households rent their homes from private or social

landlords, only 9% of the hosts we surveyed were themselves tenants. The main barrier is

contractual: while very few leases mention STLs of spare rooms specifically, most private leases

require tenants who want to let their spare rooms to a lodger to secure the consent of the landlord,

while many social sector leases prohibit the practice entirely.

Amongst both tenant hosts and all hosts surveyed, the most cited motivation for letting out a spare

room was to earn money (87% of all/81% of tenants). The second major motivation, and the primary

one for some hosts, was social. Particularly for the many hosts who live alone, spare room lets are an

important source of social contact.

Respondents to the LSE survey were asked how important earnings from STLs of spare rooms were

to their households. Almost half said they were very important or essential. Renters viewed the

2

The nights available and booked are for full year 2022. As of Jan 1 2023, 26.5% of active ever booked listings

are private rooms.

3

Airbnb data for calendar year 2022.

4

Survey asked for ‘current income’ and was conducted in September 2023.

4

earnings as more important than those in other tenures, with 35% of tenant hosts saying the

earnings from spare room lets were essential.

Spare room STLs provide affordable accommodation for a range of guests including healthcare

workers, patients, students and contractors, not just tourists. For some such guests these rooms

may be more suitable or comfortable than traditional hotels.

The use of whole homes as dedicated STLs is often criticised for reducing the availability of rental

housing, especially in cities with tight housing markets. Spare room lets have much less impact on

housing markets than lets of whole homes. Spare room lets arguably reduce options for prospective

long-term lodgers, but with few exceptions the hosts we spoke to said they wouldn’t consider having

a full-time lodger. In practice, that means many of these rooms would probably be unoccupied if

offering STLs were not an option.

In the UK and elsewhere, whole-home STLs are more often regulated than STLs of spare rooms. For

example, London limits STLs of whole homes to 90 nights/year, Scotland has recently introduced a

licensing scheme, and Northern Ireland has a certification scheme. Further regulation is being

considered by both national and devolved governments.

For tenants, there are upcoming changes in the regulation of the private rented sector. In May 2023

the government introduced the long-promised Renters (Reform) Bill, which has one major aim: to

ensure that private tenants can treat their rented properties as their homes. For example, the bill

will give tenants the right to request a pet in the property and landlords must not unreasonably

refuse such requests. This might serve as a model for STLs of spare rooms.

Recommendations

1. Government should consider the case for giving tenants the statutory right to request

permission to let out spare rooms in their homes on a short-term basis. The current

discussion of the provisions of the Renters (Reform) Bill, and the forthcoming government

framework for regulation of STLs, may present an opportunity here. The draft provision

allowing tenants to ask to keep a pet could serve as a model.

2. Some households that could benefit from such earnings—particularly tenants, who tend to

have lower incomes than owner occupiers—cannot currently let out their spare rooms. This

is because of barriers including the wording of leases, landlord insurance, mortgage

conditions and HMO licensing. In exploring ways of regulating STLs under the Levelling-Up

and Regeneration Act, the UK Government should invite interested parties to work together

to investigate these barriers in detail and explore the desirability and feasibility of making it

easier for tenant households to let out spare rooms on a short-term basis. Relevant

stakeholders include landlords (both private and social), mortgage lenders, insurance

companies, and national and local government.

3. Earnings from STLs of spare rooms can make a significant contribution to hosts’ incomes, in

some cases enabling them to remain in homes that they otherwise could not afford. The

government should consider the case for increasing the level of rent a room relief, which has

been unchanged at £7,500 per year since April 2016. If it had risen in line with inflation it

would now stand at more than £9,800. This might encourage more to consider spare room

hosting (although relatively few spare room hosts earn even as much as the current ceiling).

5

4. More research should be done into the direct and indirect effects of STLs of spare rooms, as

opposed to whole homes.

6

1 Introduction

Peer-to-peer accommodation has grown in popularity in the past few decades and Airbnb, a popular

online platform enabling people to offer homes or individual rooms for short-term let, has become a

household name in the UK and in many other countries. The ongoing cost of living crisis and the

Renters (Reform) Bill, which is currently being considered in Parliament, provide the context for this

research project. The aim was to assemble evidence on the actual and potential contribution of

earnings from spare room lets to household incomes and examine the barriers to letting out spare

rooms, especially for hosts who are themselves tenants.

The original concept of Airbnb

5

was to facilitate the letting of rooms in peoples’ homes, but the

profile of listings has evolved markedly since the company was founded in 2007. There are currently

over seven million active listings on Airbnb around the world. Four in five UK hosts list one property

on the site, and the vast majority - over 90% - list one or two properties.

According to LSE analysis around a quarter of UK active listings currently on Airbnb are 'spare room'

listings (known as ‘Private Rooms’ on the platform), most of which are in hosts’ own homes, but

most listings in the UK and in the European geographies we reviewed are for whole homes. Some of

these are the hosts’ main or vacation homes and some are dedicated full-time STLs. In many cities

with tight housing markets the conversion of permanent homes to dedicated short-term lets is seen

by governments to contribute to reduced housing supply and higher prices and rents. This has

contributed to regulation of STL activity in many places. In recent years, the company has continued

to launch specific initiatives focused on private rooms, which Airbnb’s CEO Brian Chesky has

described as “getting back to the idea that started it all – back to [Airbnb’s] founding ethos of

sharing.”

In the UK, homeowners can usually let out all or part of their properties as STLs, subject to local

regulations or registration requirements. For tenants the situation can be different: rental tenancy

agreements often contain clauses that prohibit sublets or lodgers without the explicit consent of the

landlord. These restrictions can preclude renters from offering spare rooms through sharing

platforms; renters doing so in contravention of lease terms may risk eviction. At the same time, the

government’s rent a room scheme allows anyone to earn up to £7,500 a year tax-free from renting

furnished accommodation to a lodger in their main home, which includes guests in STLs. The policy

aims to increase the supply and variety of low cost accommodation and to support labour mobility.

Hosts who are themselves tenants are also eligible for the scheme.

Most of the debate about STLs, and most of the academic literature, focuses on whole-home lets.

There is a clear gap in our knowledge about spare room lets, which this report aims to address.

Research questions and methods

The research questions for this project were:

1. How much do UK hosts earn from letting out spare rooms in their homes, and what

contribution does this make to their household incomes?

2. Apart from financial considerations, what motivates hosts to let out their spare rooms?

5

While Airbnb is not the only STL platform, its name is often used generically to refer to STLs.

7

3. In the UK, what regulatory and legal provisions make it difficult for tenants in the private

rented sector (PRS) or social housing to let out their spare rooms? What were the original

rationales for these provisions and are they still needed?

4. What would have to change to make such activity easier?

5. What is the situation with spare room lets in four major continental European cities?

Our empirical research was carried out over the period July-November 2023. We used a mix of

methods including

● Reviewing the academic and ‘grey’ literature on short-term lets

● Analysing a dataset provided by Airbnb for this project on spare room listings and hosts on

its platform. We did not have access to granular (individual) host-level data and did not

receive data from other STL platforms.

● Conducting an online survey of 1537 spare room hosts in the UK. Invitations to the LSE

survey were distributed by Airbnb to hosts offering spare rooms on the platform.

● Organising two in-person focus groups of spare room hosts letting on the Airbnb platform—

one in London, one in Liverpool. There were 12 participants in all, recruited from

respondents to the online survey, and their travel costs were covered.

● Interviewing six spare room hosts and five stakeholders with an interest in STLs. The spare

room hosts were chosen from those who volunteered to be interviewed on the LSE survey.

Stakeholder interviewees included representatives of landlord associations, local

governments and industry interest groups. To enable interviewees to speak freely we have

not named them or their organisations.

● Recruiting academic experts to complete a structured questionnaire about spare room

hosting in four comparator cities: Barcelona, Lisbon, Berlin and Paris

The research was carried out in collaboration with Airbnb, which provided anonymised data and

engagement with hosts who list on the platform. Given the popularity of the Airbnb platform in the

UK, we have interpreted the results of our research as being indicative of the wider picture for short-

term lets of spare rooms in the UK.

8

2 Existing studies of short-term lets

The body of academic literature about short-term lets is very large, and we can only give a flavour of

it in this report. Publications focus mainly on rentals of whole homes, which may be dedicated STLs

or hosts’ primary or holiday residences. Unsurprisingly, given that STL platforms are major

innovators and disruptors in travel and accommodation, most articles appear in journals of tourism

and hospitality. There is also an extensive list of publications about economic, planning and housing

issues, which are more relevant to this project.

Although spare room lets make up a significant proportion of the properties offered by hosts on

Airbnb

6

, there is little research about them specifically, which is a clear gap in the evidence base.

Two papers argue that the neighbourhood impacts of spare room lets differ from those of whole

home lets in that guests in spare rooms are less likely to be a nuisance to neighbours and letting a

spare room has less effect on local housing markets than letting a whole home. The authors argue

that they should therefore be regulated separately (Aversa and Rice 2023; Wachsmuth and Weisler

2018).

Turning to studies of STLs of whole homes, many focus on impacts on tourism and the economy.

These can be positive, especially in locations with limited hotel capacity. A recent report by Airbnb

presented data showing that listings on its platform are spatially dispersed compared to the

locations of hotels, both within cities and across wider geographical areas (Airbnb 2023a). Spare

room lets can be a useful way to increase the visitor accommodation capacity of cities hosting major

events such as music festivals (Zervas et al 2017). Spare-room STLs can reduce financial risk for the

promoters as they do not require major investment to increase guest capacity and allow local people

to benefit financially, as well as encouraging people to stay in non-touristic areas and bringing

business to different parts of the city.

A report commissioned by Airbnb calculated that stays organised through the platform contributed

£2.9 billion to the UK economy in 2022 (Airbnb 2023b). There is however a debate about how much

of this is genuinely new activity (see Gutternberg et al 2018).

Hosts benefit from letting properties on the platform. Airbnb itself reports that the typical UK host

earns on average £6,000 a year (Airbnb 2022). In a study of STLs in London, hosts reported that a

major motivation for hosting a room in their home, especially in high-cost areas, was to support

their mortgage payments (Shabrina et al 2022).

Consumers can also benefit through a greater choice of accommodation at lower prices, and some

writers argue that short-term lets can cater particularly well to travellers who are not tourists—for

example people needing residential accommodation for medical stays, or those who are temporarily

relocating for work (Suess et al 2020).

Publications in housing studies and geography tend to emphasise the negative effects of STLs. Those

with a spatial focus look mainly at high-cost cities; there are widely cited studies relating to the

housing market effects of whole home STLs in cities such as New York, London and Barcelona. The

potential issues identified are:

6

Though not on all STL platforms—VRBO’s advertising emphasises that guests always get the ‘entire place’

9

● Removal of homes from the local permanent housing stock, especially the private rented

sector. In high-demand areas this may contribute to housing supply shortages and higher

rents for local residents

● Negative local externalities (noise in particular, but also anti-social behaviour and effects on

local services), especially in neighbourhoods with concentrations of STLs

● Contribution to the financialisation of housing (Whitehead et al 2023)

In some high-demand areas, there is evidence that STLs reduce the number of homes available for

long-term letting, potentially exacerbating housing shortages and increasing rents in areas where

Airbnb properties are heavily concentrated (Shabrina et al 2022). Landlords may decide to stop

letting to permanent residents and instead offer their properties as STLs: research by Capital

Economics found that one quarter of 232 landlords surveyed let properties out on a short-term

basis, and of these 12% had previously been long-term lets (Capital Economics 2020). Similarly, a

Scottish study found that 36% of 535 landlords surveyed were hosting STLs in properties that were

previously long-term lets or owner-occupied homes (Collaborative Centre for Housing Evidence

2019).

Several authors have looked at the effects of STLs on local house prices. Research in New York found

that a doubling of the number of Airbnb listings in an area led property values to increase by 6–11%

(Sheppard and Udell 2016), although the authors noted that neighbourhoods might benefit from

STLs in other ways. Looking at London, Todd et al (2022) found that higher numbers of STL listings

were associated with a modest increase in the price of housing per m

2

; the effect was largest in

central London boroughs.

10

3 UK spare room hosts on Airbnb: tenure and earnings

Airbnb, like other STL platforms, is now well known for the letting of whole homes. However the

business started as a way of facilitating the letting of spare rooms in occupied homes, and this still

makes up a significant proportion of properties offered on the platform. According to Airbnb data, as

of January 2023, 26.5% of active ever booked listings were private rooms. The proportion varies

across the country, from under 8% in some local authority areas to over 80% in others. Spare room

lets are more common in cities than in the countryside.

A minority of listings for private rooms are not spare rooms in otherwise occupied homes; rather,

whole homes are being let out on a room-by-room basis, with guests possibly sharing kitchen

facilities or common areas. An increasing number of professional operators use the platform.

In the UK, London has the highest number of Airbnb private room listings

7

in both absolute and

relative terms. London private-room listings account for about one third of such listings in the UK;

the South West and Scotland also stood out as areas with many spare room listings. By contrast the

numbers are relatively small in several northern regions and Northern Ireland.

Most spare rooms are not available for letting every night. Across the UK geography over a five-year

period, Airbnb data show that the average private room was available for let for 17 nights/month

(204 nights/year) and was actually occupied for 6 nights/month (74 nights/year)

8

.

The LSE survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

9

provides information about the demographic

characteristics of these households. Of the survey respondents, 44% lived alone—significantly more

than the 30% share of single-person households in the UK population as a whole—and only 10% had

minor children, compared to 29% of households nationally.

About 41% of respondents had been hosting spare room lets for two years or less, and a quarter for

a year or less. A small percentage had been hosting spare rooms for more than ten years.

Tenure of hosts

Our information about the tenure of hosts comes from the LSE survey, as Airbnb’s own data do not

distinguish between homeowners and renters. Of our survey respondents, more than 90% owned

the properties where the spare rooms are located, either outright (49%) or with a mortgage (43%).

Just 9% of respondents to the LSE survey (92 in all) were tenants. This tenure profile is very different

from the profile across England as a whole, where a far higher proportion of homes are rented.

According to the 2021 Census, 37% of English homes are rented: 20% from private landlords and

17% from social landlords.

Tenants might be expected to be more motivated than owner occupiers to earn money from letting

out spare rooms, as they tend to have lower incomes than homeowners and typically a significantly

higher proportion of tenants’ income goes to the cost of housing. Outright homeowners have no

mortgage costs, and according to the English Housing Survey 2021/22, homeowners with mortgages

7

A minority of what Airbnb calls ‘private room listings’ are not spare rooms but are in whole homes that are

rented on a room-by-room basis. Such listings were included in the Airbnb data we received.

8

Airbnb data for calendar years 2018 – 2022.

9

The invitation to take part in the LSE online survey was distributed in September 2023 by Airbnb to UK hosts

with active spare room listings. About 1500 valid responses were received. The survey also captured a small

number of respondents who had previously hosted rooms on the platform but stopped.

11

spent 22% of their household income on mortgage payments. Private tenants by contrast spent on

average 33% of their income on rent (or 38% if housing support

10

was excluded).

The average rent paid by the private tenants who responded to our survey was £1,525/month, and

the median was £1,282. These figures are significantly higher than the average and median rents for

England as a whole (£960 and £825 respectively, according to the ONS). Overall, some 33% of Airbnb

private-room listings were in London, but of private room listings whose hosts were living in rented

homes, 59% were in London. Tenants’ search for additional income via STLs is doubtless partly

motivated by the high cost of rented housing, especially in London.

Although renters may need the money more than homeowners, they may in practice be less able to

offer spare room STLs. Tenants tend to live in smaller homes: the average owner occupied home is

111m

2

, vs 75m

2

for rented homes. Rented homes are also less likely to have spare bedrooms. Nearly

half of owner-occupied homes in England are ‘under-occupied’ (have two or more spare bedrooms);

the corresponding figure for private rented households is 15%.

Airbnb recently commissioned Opinium polling of 2,000 renters who have a spare room. Most said

their landlord did not allow them to let out their spare room to guests, but over half of those with a

spare room said that if their lease allowed them to open their spare room to guests they would do

so (Opinium 2023).

Earnings from spare room lets

According to data supplied by Airbnb for this research, if listings are split by local authority area the

average nightly room rate across local authority districts in 2022 was about £52. Median annual

earnings for UK spare room hosts for the period 2018-2022 were about £1200. Information from the

LSE London survey was consistent with the Airbnb data. Of respondents letting a single spare room,

roughly 50% earned £2500 or less from spare room lets in the preceding 12 months, and the vast

majority earned under £7500 (the threshold for the Rent a Room allowance). A small group (about

7%) earned £10,000 or more.

Of the 1537 respondents to the LSE survey, 734 let out a single spare room and provided information

about their income. Their average income from all sources including STLs, rounded to the nearest

£1000, was £39,000, with a median of £30,000. On average, earnings from letting out a single spare

room accounted for 16% of household income for our survey respondents. The median was 9%.

Looking at tenants only, there were 62 respondents who were letting a single room and provided

income information. On average, earnings from this activity accounted for 9% of household income;

the median was the same.

Table 1: Contribution of spare room income for UK households letting single spare room

ALL TENURES (n=734)

TENANTS ONLY (n=62)

Total household

income (rounded)

Spare-room earnings

as % of household

income

Total household

income (rounded)

Spare-room

earnings as % of

household income

average

£39,000

16%

£36,000

9%

median

£30,000

9%

£36,000

9%

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

10

Legacy Housing Benefit or the housing element of Universal Credit. 25% of private renter households

received housing support to help pay their rent in 2021/22.

12

Those letting two spare rooms and for whom we have income figures (78 respondents) had

somewhat higher overall incomes and spare room letting made a slightly higher contribution to

those incomes (19% on average).

Table 2: Contribution of spare room income for UK households letting out two spare rooms (all

tenures, n=78)

Total household income (rounded)

Spare-room earnings as % of household

income

average

£43,000

19%

median

£30,000

10%

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

Respondents to the LSE survey were asked how important earnings from STLs of spare rooms were

to their households. Almost half said they were very important or essential. Renters viewed the

earnings as more important than homeowners, with 35% of tenant hosts saying the earnings from

spare room lets were essential.

Figure 2: Importance of earnings from spare room letting

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

Many working-age hosts said the income from spare room lets enabled them to pay their rent or

mortgage. One said it allowed them to stay in their home after breaking up with their partner;

another said the income supported them when they could not work following a long-term illness.

Amongst those nearing or in retirement, a number said earnings from spare room lets meant they

could stay in their family homes after their children had left and/or their partners had died.

My wife died five years ago and the kids moved out. I was kind of seriously considering having to

reinvent myself, especially when the cost-of-living crisis was starting to bite. And I was feeling like, do

I have to go back to work full time? Or do I try and do something else to try and actually get some

13

income from the house… And I mean, it's made a huge difference. To be honest, it's been the

difference between having to sell the house and downsize, and being able to stay in the house.

11

Income from spare room lets could substitute for employment income. Several hosts said that by

letting spare rooms they could afford to retire early or take time off work. Some used earnings from

spare room lets to pay for holidays or other exceptional expenditure; one said they personally did

not need the income but saved it to give to their grandchildren.

I’m taking a break from my work so it's really giving (my partner) some reassurance of some income

coming in this period.

I use it for maintenance of the house, if I need a new car, you know, and I'm quite upfront--if I am

chatting (to a guest), I will say, ‘You’re my new sofa!’

Most hosts said spare room earnings had become more important over time, partly due to increases

in the cost of living and particularly energy prices. Three quarters said their costs had risen over the

previous year, citing utility bills, food and mortgages. Of tenants, 50% had seen their rents increase.

Table 3: Reasons for increased household costs (of those whose costs had increased, n=804)

Utility bills

96%

Food

83%

Mortgage payments

29%

New contracts (phone, streaming services)

15%

Additional family to support

15%

Rent increases

9% overall (50% of renters)

Other

11%

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

Case study 1: Richard

Richard lives alone in a modern two-bedroom flat in central London, which he rents. He is

currently unable to work due to long term health problems. He first started listing a double

bedroom with ensuite on Airbnb a year and half ago to generate funds to stay in his flat.

Room letting on Airbnb is Richard’s main source of earnings; without it, he says, he would

probably have to claim benefits. The money has become more important as bills have gone up.

Richard considered finding a full-time housemate as there would be less work involved, but felt

this would bring in less money and wouldn’t fit as well with his lifestyle.

Aside from the money, Richard’s main reasons for letting out the room are to meet people from

all over the world and to have company at home. Richard encourages longer stays to make the

cleaning and work involved worthwhile, and on average people stay for seven nights. His guests

are mainly people travelling to London for holiday.

Richard provides guests with snacks on arrival and is happy to advise them about where to go in

London. He takes pride in making sure people have a good experience in the capital.

11

Quotes are verbatim from interview and focus group participants, or from free-text responses to host

survey.

14

A minority of respondents had seen household expenditure decrease. Most (71%) said this was due

to deliberate cost savings. Other contributors included children moving out of the family home,

paying off the mortgage, and retirement.

In qualitative fieldwork carried out by LSE in the course of this research, hosts described varying

approaches to setting prices. Those who relied on spare room income for essential expenditure paid

keen attention to occupancy rates and pricing. Hosts for whom the money was just ‘nice to have’

tended to take a less strategic approach. Some hosts were very tactical, moving prices up and down

at different times of year; others charged a low rate at all times to try to maintain maximum capacity

(although some participants said very low prices attracted more difficult guests).

We asked hosts about the extra work and cost involved with letting out the room. None apart from

one commercial host had formally calculated the time/cost it took to clean the room, although

several had minimum stays of two or more nights as they felt it was too much work to turn the room

around after a single night.

In the focus groups, hosts discussed utility bills. Some liked having a reason to keep the heat on,

while others said rising utility prices in combination with changing guest behaviour had affected

energy bills; indeed some had stopped letting out their rooms in winter for that reason.

Case study 2: Sarah

Sarah lives alone in a two-bedroom flat in an outer London borough. She works part time for the

local council and has two adult sons. She lets out a cosy double bedroom on Airbnb; guests have

access to a shared bathroom, living room and kitchen.

When her sons first moved out, Sarah rented the room to a full time lodger, but when one son

wanted to move back home temporarily the lodger had to go. She then began letting the room on

Airbnb because it was more flexible--she can easily turn down a booking request or make the

room unavailable on the platform if necessary.

Sarah began letting on Airbnb to supplement her income. She has a minimum stay of two nights

to ensure that the time and effort of changing the sheets and cleaning the room is worth it for the

money she earns. She now relies more on earnings from hosting on Airbnb because of rising

energy costs; indeed Sarah puts these earnings on the electricity meter, so she knows the money

has gone towards something important. Without this source of money Sarah says she could find

ways to cope, but would have to cut down on daily expenditure and might have to rely on her son

for support.

Sarah’s landlord is aware she lets the room out on Airbnb and has no problem with it as long as

she pays her rent on time. Sarah likes to make sure her guests feel welcome and comfortable in

her home, and says she always receives very good ratings.

15

4 Hosts’ motivations for renting out spare rooms

The LSE London survey asked hosts about their motivations for renting out their spare rooms.

Multiple responses were permitted.

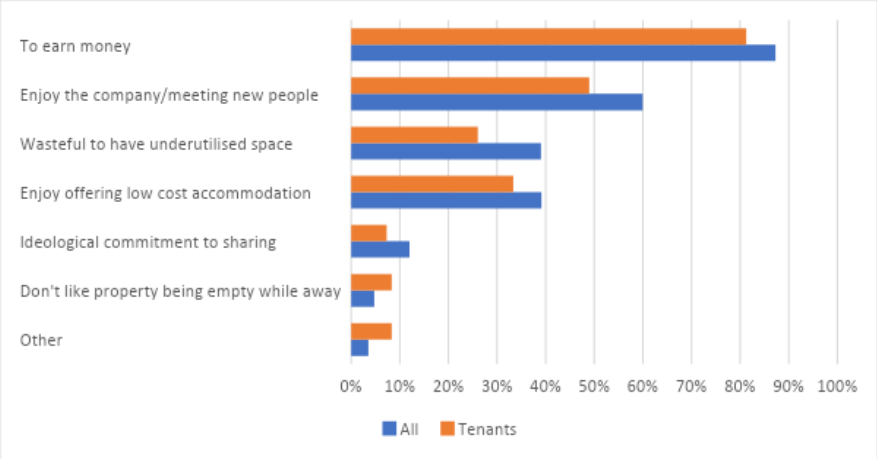

Figure 3: Why do you let out your spare room? (tick all that apply) (all n=1537; tenants=96)

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

Figure 3 indicates that amongst both tenant hosts and all hosts, the most cited motivation for letting

out a spare room was to earn money (87% of all/81% of tenants). For most hosts this was not the

only reason they let out rooms; many said they enjoyed meeting new people, thought it was a waste

to have underused space, and/or enjoyed offering low-cost accommodation.

Amongst those who cited more than one motivation, most said the main one was financial. The

second most common motivation was for company and meeting new people. Some hosts saw letting

rooms as a way of helping others—one said,

I remember being an impoverished backpacker many years ago and always found accommodation

was a limiting factor when travelling. Offering my spare room has helped many youngsters.

Several focus group participants had initially started letting rooms to supplement income, but also

found they enjoyed interacting with guests. Several commented that they didn’t expect to enjoy this

aspect so much, and that it was one of the main reasons they continued to let their spare rooms.

Interestingly, all but two of our interviewees and focus group participants lived on their own, so

companionship was important to them. Several said they had formed close friendships with certain

guests, some of whom had returned to stay several times.

The main motivation was money but also meeting new people. I love the people that stay. I have met

so many good friends through doing it.

It's nice to actually have someone to talk to someone to get to know and know where you're from

(and) what you're doing. (Otherwise) I would have just been there on my own and talking to the cat.

Yeah, I did it because I've got two spare bedrooms and the house was too big for me on my own. But

the main thing I found is meeting people. I just really, really enjoy it.

16

Some hosts went above and beyond for their guests, providing lifts to the airport, home-cooked

evening meals, and even life advice.

We give people lifts, this guy that's working at the science place, it would take (him) an hour and a

half on the bus and it takes us 15 minutes. And we take people to our local rock festival.

Case study 3: Hannah

Hannah lives alone in a two-bedroom house in a small suburb outside Birmingham. She started

letting out her spare room six years ago, when her daughter went travelling.

Hannah tries to make her guests feel welcome: when they arrive she always gives them a home

cooked meal and talks them through the house rules. Some guests have become close friends:

she has cooked for people who were ill, and one guest offered her a free holiday in their second

home.

Hannah started letting the room out to make money. The income was particularly welcome when

it enabled her to take some time off work when she was unwell. Her minimum stay is one week;

she feels it isn't worth the effort to clean the sheets and the room for shorter stays. The room is

almost fully occupied. When Hannah first started, she set her prices at the same level as other

similar rooms in the area, but when she reached 100% occupancy she decided to put them up.

Lodgers vs Airbnb guests

We asked hosts why they had chosen to let rooms via Airbnb rather than have long-term lodgers.

Most said they preferred not to have someone in their home all the time and/or that they wanted to

keep the room available for family and friends occasionally. Other reasons for preferring STLs

included meeting a steady stream of new people; difficulties finding ‘good lodgers’ that hosts could

get along with; and higher income from STLs than from lodgers. Two of our focus group participants

had previously tried having long-term lodgers but preferred the flexibility of letting through Airbnb.

I prefer the flexibility that is more rewarding financially, and is less invasive in terms of presence in

the house.

One local government interviewee said it would be preferable if spare rooms accommodated long

term lodgers, to help provide a stable home for someone. We note that a guest can book a stay on

Airbnb for up to two years, but this remains at the hosts’ discretion.

Former hosts

Our survey captured a few former hosts who had taken a break from accepting guests or stopped

entirely. Some felt the earnings no longer justified the work involved; others reported bad

experiences with guests that made them decide not to continue.

17

5 UK regulatory, legal and contractual context

The two main characteristics of spare room lets are that they

● Involve guests who do not live permanently at the property (stays are generally though

not always less than 30 days at a time)

● Involve only a part of a dwelling

The wording of most existing legislation and regulation focuses on one aspect or the other—so most

of the rules around short-term lettings apply to entire dwellings, while the rules around renting out

part of a dwelling (to lodgers or subtenants) assume that this is for a longer period.

Existing STL regulation in England and Wales

In those parts of England and Wales that regulate STLs (most notably London), such regulation

focuses almost exclusively on lets of whole homes. In Scotland, however, a licence is required for

both home sharing (which is defined in legislation as offering a spare room when the host is present)

or home letting (letting out a spare room while the host is away). At the time of writing, there is no

specific use class for short term holiday lettings in England

12

, although the Government is currently

consulting on how one might be introduced. While there is currently no national-level limit on the

days a property can be let out, new rules being proposed by the Department for Levelling-up,

Communities and Local Government may cap the number of nights that someone can host in their

own home without requiring planning permission.

Some individual local authorities have imposed their own limits: in London, regulations limit the

short-term letting of whole homes to 90 nights/year without planning permission, but there are no

corresponding limits for spare rooms.

For UK income tax purposes, hosts can exclude up to £7,500 of earnings from STLs of spare rooms

under the Rent a Room allowance. About 60% of the hosts we surveyed made use of this scheme,

with just under half saying it covered all of their spare room earnings. However almost a quarter said

they were unaware of the scheme.

Future regulation in England & Wales: Renters (Reform) Bill and new STL rules

The Levelling-Up and Regeneration Act, which received Royal Assent in October 2023, includes

provision for a registration scheme for STLs in England. The consultation on the mechanics of this

scheme have closed, and the government has not yet announced its plans, including whether spare

rooms will be in the scope of activity that needs to be registered. Wales is also consulting on a

statutory licensing scheme for visitor accommodation.

For tenants, there are upcoming changes in the regulation of the private rented sector. In May 2023

the government introduced the long-promised Renters (Reform) Bill

13

. One of the aims of the bill is

to ensure that private tenants can treat their rented properties as their homes.

12

Some councils put holiday lets into the sui generis planning class.

13

The government promised to bring this bill into law before the next election (latest January 2025). As of late

November 2023 the Bill is in committee stage and 276 amendments had been tabled, so the final version may

differ significantly from the original text. Guidance about the pet provisions, including some comments about

insurance appear in DLUHC guidance here: https://www.gov.uk/guidance/renting-with-pets-renters-reform-

bill

18

Among its provisions is a change in the position regarding pets: tenants will be given the right to

request a pet in the property, which the landlord must consider and cannot unreasonably refuse. To

support this, landlords will be able to require pet insurance to cover any damage to their property

(DLUHC 2023). Tenants must confirm in writing that they have pet insurance or will cover the

landlord's insurance in case of pet damage. It might be possible to adopt a similar approach for

short-term lets of spare rooms.

STL regulation in Scotland

Housing policy is a devolved responsibility in Scotland, and regulation of STLs is significantly tighter

than in England. There is a new nationwide licensing scheme for short-term lets of both whole

homes and spare rooms; hosts were required to apply for a licence by October 2023. There are four

categories, three of which could apply to spare room STLs. These are ‘home sharing’ (letting all or

part of the host’s home while the host is there); ‘home letting’ (the same, but when the host is

absent); and ‘home letting and home sharing’ (covering lets when the host is present and when they

are not)

14

.

Scottish Government guidance makes clear that hosts must have the permission of property owners

to apply for a licence:

If you do not own the premises, then you must have the permission of the owner(s) to make

an application for a licence. For example, you may be a tenant and want to use your

property for home sharing or home letting. You should first make sure that your tenancy

agreement would allow you to do this in general terms and then seek the specific permission

of your landlord (Scottish Government 2023, para 2.9).

All STLs including spare room lets must comply with mandatory safety conditions, which include

regular gas and electrical safety inspections. Licences set a maximum occupancy. Individual Scottish

local authorities can also impose additional licence conditions, as well as restrictions to require

planning permission for dedicated whole-home STLs in ‘control areas’. Edinburgh became Scotland’s

first designated short-term let control area in September 2022. Since doing so, Edinburgh City

Council has lost judicial reviews of both planning policies it tried to introduce to implement its

control area; elements of both policies were found to be unlawful. Other local authority areas in

Scotland will have to consider these judgements when implementing their respective control areas.

Subletting, lodgers and tenancy agreements

Guests in spare rooms STLs generally occupy the space with a licence rather than a lease, as do

lodgers. In both the social and private rented sectors, it is common for leases to contain clauses that

require that tenants to secure the landlord’s permission before subletting and/or taking lodgers, or

simply prohibit these activities entirely. The Prevention of Social Housing Fraud Act 2013 made the

unlawful subletting of social housing properties a criminal offence. Research by the Residential

Landlords Association found 7% of landlords surveyed reported they had found their tenant sub-

letting via short-term let platforms. Owner occupiers who are leaseholders in blocks of flats may be

prohibited from using their property for short-term lets under the terms of their lease agreements;

such restrictions would also apply to the tenants of landlords who are leaseholders. Some

homeowners may need to seek permission from their mortgage providers.

14

The final category is ‘secondary letting' (letting a property where the host does not normally live, e.g. a

second home or holiday let).

19

Stakeholders interviewed for this report said that in their experience, landlords often want to have

some control over who is in their property. Some are happy to allow tenants to take lodgers if it will

help them sustain their tenancy and if a reference check is carried out, although they felt that most

would prefer a formal tenant rather than a lodger.

Government’s model lease: private rented sector

In the private rented sector in England

15

, the provisions of the government’s model agreement

16

for

a shorthold assured tenancy say that tenants who wish to sublet the entire property or a part of it,

for a longer or shorter period, must request permission from the landlord and that such permission

should not be unreasonably withheld. Note that there is no requirement for landlords to use this

model lease.

Regarding potential sub-lets, the accompanying guidance states that

‘the tenant will want to confirm the prospective sub-tenant’s identity, credit history and

possibly employment’

The government’s model lease is silent on the topic of lodgers, who occupy under a licence rather

than a lease. The Airbnb platform provides hosts with some information about guests based on their

user profiles, but this does not include credit history or employment.

There are other constraints that can impact the viability of spare room lets in rented homes. For

example, offering the property as a short-term let may invalidate the insurance or mortgage

conditions of the landlord (that is, the owner of the property). Rental properties that are licenced as

Houses in Multiple Occupation (HMOs) have rules about maximum number of occupants, which

having a spare room guest may breach. Similarly, if the guest is accommodated in a room that is

deemed too small to be used as a bedroom (any room of less than 4.64 m

2

), the landlord could be

subject to enforcement action.

Expert interviewees said one way forward could be to have lease provisions requiring tenants to

seek permission for spare room lets from the landlord, and require landlords not to withhold

permission unreasonably.

NHF model lease: Housing associations

Social landlords include local authorities (councils) and housing associations. Social tenants with

‘secure’ tenancies (most council tenants and some longtime housing association tenants) have a

legal right to take a lodger. Those with other types of tenancies may not have this right. Subletting

by local authority tenants is often prohibited completely.

For housing associations, model lease agreements are published by the National Housing Federation,

though social landlords are not obligated to use them. The NHF publishes three model tenancy

agreements: for non-shorthold tenancies (which covers most housing association tenancies),

assured non-shorthold tenancies and assured shorthold tenancies.

All three model agreements have the same provisions regarding overcrowding, lodgers and

subletting. These appear in Table 4 below.

15

Lease arrangements are different in Scotland.

16

https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/model-agreement-for-a-shorthold-assured-tenancy

20

Table 4: Relevant provisions of NHF model tenancies for housing associations

Overcrowding

(15) Not to allow more than … persons to reside at the Premises.

Lodgers

(16) Before taking in any lodger to inform the Association of the name, age and

sex of the intended lodger and of the accommodation he or she will

occupy.

Sub-letting

(17) Not to grant a sub-tenancy of the Premises or any part of the Premises.

Under the NHF model tenancies, the landlord may specify a maximum number of occupants who can

reside at the home. Hosting spare room guests could potentially contravene this provision, if they

were considered to ‘reside’ at the property. The NHF model leases do permit tenants to take in

lodgers, requiring only that they inform the landlord. Sub-letting is not permitted. This is different

from the model tenancy for private rented housing, which does not mention lodgers and permits

sub-letting with the permission of the landlord.

Airbnb’s own insurance

Airbnb’s ‘AirCover for Hosts’ programme is automatically available to all Airbnb hosts at no

additional cost, with no opt-in required. The programme includes host damage protection and host

liability insurance, amongst other protections, though Airbnb emphasises that it is not a substitute

for personal insurance. In particular, ‘AirCover for Hosts’ only applies to accommodations booked via

the Airbnb platform. If guests do not pay for the damage caused to an Airbnb host’s home or

belongings, host damage protection is in place to help reimburse costs up to US $3 million for certain

damage and any consequential lost Airbnb booking income. Host liability insurance provides up to

US $1 million in coverage if a host is found legally responsible for injury to a guest, or damage to or

theft of their belongings, while staying at the host’s property (certain exclusions apply).

Evidence about tenants and their leases

Of tenants who responded to the LSE survey, 42% said their lease explicitly permitted subletting,

while 16% said it did not. Those renting from friends or family members were more likely to say that

their lease allowed them to sublet.

Table 5: Whether lease allows spare room letting (tenants responding to LSE survey, n=93)

Source: LSE London survey of Airbnb spare room hosts

Significant proportions of respondents were not sure whether their lease permitted subletting (20%)

or preferred not to say (22%). Some 48% of respondents said their landlord was aware that they

were letting their spare room out on Airbnb. Just two respondents said their landlord received a

share of income from the Airbnb lets, with one getting a flat amount and the other a percentage.

Because the focus of this work was spare room lets in rented homes, we oversampled tenants in our

qualitative research: of the six hosts we interviewed, three were tenants. One said their landlord

was aware they were letting the room on Airbnb, one thought they might know, and one said their

landlord was unaware. All three tenant hosts said the income from spare room lets helped them

meet household costs.

Lease allows subletting

Landlord aware of spare room letting

Yes

42%

48%

No

16%

24%

Not sure

20%

9%

Prefer not to say

22%

19%

21

6 Spare room letting in Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon and Paris

To put the UK in context, this section briefly summarises the regulatory approaches to STLs in other

countries, focusing particularly on four European cities: Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon and Paris.

Across the world, national and local governments have increasingly been regulating and limiting

short-term lets, especially in major tourist destinations and cities with tight rental markets.

According to Leshinsky (2018),

The justifications for government regulation appear to be one or more of the following:

protecting health and safety of guests using (short-term rentals), protecting broader social

welfare – primarily the access to affordable housing – of the existing community and

protecting the future amenity of neighbourhoods for local residents. (p. 419)

Requiring hosts to register is often a first step. Limits on the number of nights per year that the

property can be let out through STL platforms are also common; typically the ceiling is about 90.

Some jurisdictions require the host to be physically present if spare rooms are let. A few places have

imposed blanket prohibitions, at least for new STLs. STL platforms liaise with governments on

measures like procedures to take down listings that exceed annual limits, although hosts and guests

may both try to evade restrictions and enforcement can be challenging.

An analysis of different regulatory approaches to short-term lettings across 12 European cities found

that there were very few regulations in place for short-term room lets, as opposed to whole house

lets, as they are generally viewed by housing experts as less damaging to the wider housing market

(Colomb and Moreira de Souza 2021).

The four cities

As part of this study we worked with European housing experts to understand the current situation

in four European cities: Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon and Paris.

Table 6 gives summary information from Airbnb data about the listings in each city as of the

beginning of 2023. Note that the data relate to the formal administrative boundaries of each city,

not to the wider metropolitan areas which are much larger. The proportion of all listings that are for

individual rooms

17

(categorised by Airbnb as ‘private rooms’) varies from 13% in Paris to 41% in

Berlin. Lisbon has the highest proportion of spare room listings booked for more than half the nights

of the year, at 21%.

Table 6: Summary of Airbnb listings in four European cities

Barcelona

Berlin

Lisbon

Paris

Private rooms as % of active listings

38%

41%

20%

13%

Average nights p.a. hosted in spare rooms

68

40

61

32

% of private room listings booked for <30

nights/year

27%

41%

33%

47%

% of private room listings booked for >181

nights/year

18%

15%

21%

13%

17

Not all private room listings are for spare rooms; some relate to entire properties that are rented on a room-

by-room basis, often by commercial operators. It was not possible to distinguish these listings from spare

room listings in the Airbnb dataset we analysed.

22

Source: LSE London analysis of data from Airbnb and Eurostat

Policy debates

In all four countries there is an active debate about STLs and how and whether they should be

regulated. Politicians and housing activists draw a link between housing affordability issues and the

growth of whole-home STLs, which are seen to remove dwellings from the permanent housing stock.

This is particularly an issue in larger cities, which tend to have a relatively inelastic housing supply. In

Portugal, the debate about STLs is highly polarised: some emphasise the importance of STLs for local

economies and host incomes, and point to their positive impacts in terms of job creation and

rehabilitation of derelict housing. Others emphasise the negative impact of STLs on the availability of

rental housing and the cost of housing in places with inelastic housing supply. In France and

Germany, conversion of permanent housing to dedicated STLs is seen as a way to circumvent rent

control.

Generally, however, the political and media debates in these countries relate mostly to STLs of

entire homes; there is little discussion of spare room lets.

Regulatory situation in each city

Our academic experts provided information about the current regulatory and policy situation around

STLs, and in particular spare rooms, in each city; this information was checked by Airbnb offices in

each country. This information is summarised in Table7, and a fuller description for each city appears

in Annex 2. It is important to emphasise that these are only summaries of what are very complex

systems, and reflect the situation prevailing in autumn 2023.

23

Table 7: Summary of policy around STLs for spare rooms Barcelona, Berlin, Lisbon and Paris

Barcelona

Berlin

Lisbon

Paris

Level at which

rented homes &

STLs regulated

STLs: Regional & local

Rented housing: National

STLs: Individual federal states

and city

Rented housing: National

National and city

STLs: local

Rented housing: National

Registration of

STLs required?

Yes but no longer issued in

Barcelona for spare rooms or

whole homes

Yes for entire dwellings and

spare rooms

Yes for entire dwellings and

spare rooms. New registrations

of entire dwellings is suspended

(spare rooms exempted)

Yes for entire dwellings only

(rooms do not have to register)

Limits and

incentives on

STLs of entire

dwellings

Time limit of 5 years (+5 in some

cases) for holders of existing

licences; new licences no longer

issued in Barcelona

Berlin law limits STLs of dwellings

that are not primary homes to 90

days/year

(1) Reassessment of all existing

licences every five years, starting

in 2030; (2) expiration of licences

when transmitted to other

owners (except for succession);

(3) expiration of licences when

not used (rooms exempted when

rented out less than 120

nights/year); and incentives to

return STLs to permanent

housing stock

Primary homes can be rented as

furnished tourist

accommodation for max 120

days/year. Secondary homes

(incl. investment properties)

require an authorisation / licence

which is hard to obtain

Limits on STLs of

spare rooms in

occupied

dwellings

In Catalonia, spare room lets

only allowed if host lives in the

dwelling. In Barcelona, licences

required and the city has not

granted new ones since 2021

No limit on number of nights if

<50% of a main home

Maximum of 3 rooms in

permanent home of host, rooms

limited to 120 nights/year

For chambres chez l’habitant, no

limit on number of nights in

host’s own home

Tenants as hosts

Permission from owner of the

dwelling required; rental

contracts can include blanket

ban

Permission in writing from the

landlord required

Permission in writing from the

landlord required

In private rental, permission in

writing from landlord required.

Social tenants cannot host STLs.

Nightly price must not exceed

that of the main lease

24

Barcelona

Berlin

Lisbon

Paris

Other

restrictions

Homeowners’

associations can prohibit

STLs in their buildings

Homeowners‘ associations can

prohibit STLs in their buildings

Secondary home STLs are forbidden in

many buildings held in co-ownership where

the rules prevent “commercial activity”

Taxation of

spare-room STL

income

Taxed as other rental

earnings

Income net of costs is

subject to income tax.

Hosts must collect city

tax

Taxed on same basis as guesthouses

or small family hotels, with

equivalent bureaucratic

requirements

Taxed as rental of furnished

accommodation

Source: LSE London summary of material from European experts (see Annex 2)

25

All four case study cities require registration of spare room lets. Barcelona requires licences for spare

room lets but stopped issuing new ones in 2021, so only those hosts who had licences already can

legally let out a spare room.

The rules governing rental tenancies are usually national rather than local. In all the case study

countries, private tenants require formal permission from their landlords in order to undertake

spare room lets

18

. Rules for social tenants may differ—for example in France social tenants may not

sublet or undertake short-term spare room lets.

Summarising the international picture

Evidence from these case studies suggests a pattern of increasing regulation of STLs, responding in

part to concern about their effects on tight housing markets. Common control mechanisms include

registration, licensing and limits on the number of nights that a dwelling can be let. The focus tends

to be on whole-home lettings, especially of dwellings used exclusively as STLs; few jurisdictions limit

spare room lets in primary homes.

18

The situation is changing constantly; as this report was being written a federal court in Germany ruled that

landlords are obliged to allow tenants to sublet their spare rooms https://www.spiegel.de/wirtschaft/bgh-

mieter-hat-anspruch-auf-untervermietung-von-teilen-seiner-wohnung-a-ee9b64f0-9b21-4e82-a772-

1c3d18d2abce The ruling applied to long-term lets, not STLs.

26

7 Discussion and conclusions

Most of the focus in both academic and public policy debates is on STLs of entire properties. Even

though spare room lets make up a significant proportion of listings on the Airbnb platform, there is

little research into the experience of hosts and guests and their wider effects on housing markets

and neighbourhoods. This report is an attempt to address this gap.

For most hosts, the main motivation for letting spare rooms was financial. Nearly half of hosts

surveyed said the income from spare room lets was essential or very important to meeting

household costs, and many said this had become more important as housing costs (rents, mortgages

and utilities) had gone up. In the current economic climate, spare room lets can be a way for people

to increase their earnings without having to take on extra hours at work.

The second major motivation, and the primary one for some hosts, was social. The individuals we

met in our interviews and focus groups were notably gregarious and outgoing—unsurprisingly, given

that they are happy to welcome strangers into their homes. Particularly for the many hosts who live

alone, spare room lets are an important source of social contact.

Spare room STLs provide affordable accommodation for a range of guests including healthcare

workers, medical patients, students and contractors, not just tourists. For some such guests these

rooms may be more suitable or comfortable than traditional hotels.

In terms of potential impact on housing markets, spare room lets arguably reduce options for

prospective long-term lodgers, but with few exceptions the hosts we spoke to said they wouldn’t

consider having a full-time lodger. In practice, that means many of these rooms would probably be

unoccupied if offering STLs were not an option. In some cases, spare room lets enable hosts to

remain in larger homes (often family homes) that they might otherwise have had to sell.

Tenants made up less than 10% of hosts surveyed, even though they might benefit more than owner

occupiers from the extra income. This partly reflects the fact that standard lease provisions either

prohibit spare room lets (often in the social sector, and sometimes in the private sector) or require

the landlord’s permission; it is also much less common for tenants to have spare rooms in their

homes. Even though up to £7500 in earnings from spare room lets is tax free under the rent a room

allowance, various barriers mean that few tenants are able to benefit.

27

8 Recommendations

1. Government should consider the case for giving tenants the statutory right to request

permission to let out spare rooms in their homes on a short-term basis. The current

discussion of the provisions of the Renters (Reform) Bill, and the forthcoming government

framework for regulation of STLs, may present an opportunity here. The draft provision

allowing tenants to ask to keep a pet could serve as a model.

2. Some households that could benefit from such earnings—particularly tenants, who tend to

have lower incomes than owner occupiers—cannot currently let out their spare rooms. This

is because of barriers including the wording of leases, landlord insurance, mortgage

conditions and HMO licensing. In exploring ways of regulating STLs under the Levelling-Up

and Regeneration Act, government should invite interested parties to work together to

investigate these barriers in detail and explore the desirability and feasibility of making it

easier for tenant households to let out spare rooms on a short-term basis. Relevant

stakeholders include landlords (both private and social), mortgage lenders, insurance

companies, and national and local government.

One approach to investigate would be to give spare room hosts the right to request

permission from their landlords to let their spare room on a short-term basis (similar to the

right conferred by the Renters [Reform] Act for tenants to ask to have a pet). Tenants would

have to confirm in writing that they had insurance or would cover the landlords’ costs in

case of damage; landlords could not refuse such requests unreasonably.