Utah Law Review Utah Law Review

Volume 2021 Number 5 Article 2

12-2021

COVID-19 Protocols for NCAA Football and the NFL: Does COVID-19 Protocols for NCAA Football and the NFL: Does

Collective Bargaining Produce Safer Conditions for Players? Collective Bargaining Produce Safer Conditions for Players?

Michael H. LeRoy

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.law.utah.edu/ulr

Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Health Law and Policy Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Michael H. LeRoy, COVID-19 Protocols for NCAA Football and the NFL: Does Collective Bargaining

Produce Safer Conditions for Players?, 2021 ULR 1029 (2021). https://doi.org/10.26054/0d-h24h-2yfs

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Utah Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for

inclusion in Utah Law Review by an authorized editor of Utah Law Digital Commons. For more information, please

contact valeri.craigle@law.utah.edu.

1029

COVID-19 PROTOCOLS FOR NCAA FOOTBALL AND THE NFL:

DOES COLLECTIVE BARGAINING PRODUCE SAFER CONDITIONS

FOR PLAYERS?

Michael H. LeRoy*

Abstract

My study surveyed all NCAA football programs in Power 5

conferences during the 2020 season to compare their COVID-19 safety

protocols to those in the NFL-NFLPA labor agreement. College protocols

lacked input from a players association. In contrast, the NFL and their

players collectively bargained a seventy-two-page agreement for COVID-

19 protocols. Policies from nineteen college football programs fell far

short of NFL-NFLPA standards, scoring ten to thirty points out of the

forty-five safety points in the NFL labor agreement. College policies were

strongest for symptom checking and cardiac evaluations. However, most

college policies failed to identify players with individual risk factors and

provide them extra medical monitoring; additionally, no college policy

reported using location tracking technology for contact tracing. The

NFLPA also had a whistleblower hotline to report noncompliance with the

labor agreement, but college policies did not. I conclude that collective

bargaining provided NFL football players with superior safeguards

compared to those for college players. Like unionized construction firms,

which have better safety records than nonunion firms, the NFL is safer

than the NCAA for football players because of collectively bargained

practices. This study supports treating college players as employees rather

than amateurs because employment is necessary to form a union.

I. INTRODUCTION

A. Research Question and Overview of Methods and Findings

Do college football players have the same safety protections for the COVID-19

virus as union-represented NFL players,

1

even though they cannot form a labor

union?

2

The pandemic produced a natural experiment to determine if a players

* © 2021 Michael H. LeRoy. Professor, School of Labor and Employment Relations,

and College of Law, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (mhl@illinois.edu).

1

See NAT’L FOOTBALL LEAGUE, NFL-NFLPA COVID-19 PROTOCOLS FOR 2020

SEASON (2020), https://static.www.nfl.com/image/upload/v1604923568/league/qj8bnhpzrnj

evze2pmc9.pdf [https://perma.cc/BJ27-GDYZ] [hereinafter ADDENDUM] (providing several

policies and protections to union-represented NFL players).

2

See Nw. Univ., 362 N.L.R.B. 1350, 1352–54 (2015) (rejecting an effort by football

players to form a union under the National Labor Relations Act). The Board declined to

1030 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

association produces more comprehensive testing and mitigation procedures than

college football, where conferences and schools unilaterally implemented COVID-

19 protocols.

3

The virus posed similar risks to both player groups. Therefore,

protocols for infection testing, quarantining, returning to competition, and contact

tracing should have been similar for professional and college players.

To answer my research question, I sent Freedom of Information Act (FOIA)

requests to all fifty-three public universities and colleges in the Power 5 conferences,

and the same request to twelve legal departments of private schools.

4

My research

strategy aimed to elicit answers, not rejections, under these laws. Thus, I simplified

and limited my requests.

5

The NCAA has been criticized since the 1970s for transmuting a de facto

employment relationship into a self-enriching amateur athlete model.

6

My research

assert jurisdiction, noting that while approximately 125 schools comprise the NCAA’s upper

tier of FBS football competition, the NLRA applied to only seventeen private schools.

Allowing only a small fraction of players at these private schools to form a union would

destabilize labor relations and league-based competition in college football. Id. at 1354.

3

Compare Alan Blinder, Lauryn Higgins & Benjamin Guggenheim, College Sports

Has Reported at Least 6,629 Virus Cases. There Are Many More, N.Y. TIMES (Dec. 11,

2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/11/sports/coronavirus-college-sports-football.

html [https://perma.cc/R4AD-BZGG] (stating that “[t]esting standards vary from one

conference to the next” and that over 6,600 student-athletes were infected and a number of

games were canceled), with Kevin Siefert, How the NFL Navigated COVID-19 this Season:

959,860 Tests, $100 Million and Zero Cancellations, ESPN (Feb. 12, 2021),

https://www.espn.com/nfl/story/_/id/30781978/how-nfl-navigated-covid-19-season-959860

-tests-100-million-zero-cancellations [https://perma.cc/5GLF-EB7F].

4

For the list of private and public schools, see infra Table 1.

5

For my FOIA inquiry, see infra Section III.B.

6

An early article expressing skepticism about the student-athlete model is Stephen

Horn, Intercollegiate Athletics: Waning Amateurism and Rising Professionalism, 5 J.C. &

U.L. 97, 97 (1978) (“Too often the jockeying for power within the NCAA has reflected the

economic positions between institutions rather than concerns about what should be the basic

purpose of the organization: the protection of student-athletes from unscrupulous actions by

those who would exploit them for their own purposes.”). More recently, research has focused

on the strong comparison of NCAA amateurism to professional employment. See Richard

Smith, The Perfect Play: Why the Fair Labor Standards Act Applies to Division I Men’s

Basketball and Football Players, 67 CATH. U.L. REV. 549 (2018); Sam C. Ehrlich, The FLSA

and the NCAA’s Potential Terrible, Horrible, No Good, Very Bad Day, 39 LOY. L.A. ENT.

L. REV. 77 (2019); Marc Edelman, From Student-Athletes to Employee-Athletes: Why a “Pay

for Play” Model of College Sports Would Not Necessarily Make Educational Scholarships

Taxable, 58 B.C. L. REV. 1137 (2017); Richard T. Karcher, Big-Time College Athletes’

Status as Employees, 33 A.B.A. J. LAB. & EMP. L. 31 (2017); Jay D. Lonick, Bargaining with

the Real Boss: How the Joint-Employer Doctrine Can Expand Student-Athlete Unionization

to the NCAA as an Employer, 15 VA. SPORTS & ENT. L.J. 135 (2015); Michelle A. Winters,

Comment, In Sickness and in Health: How California’s Student-Athlete Bill of Rights

Protects Against the Uncertain Future of Injured Players, 24 MARQ. SPORTS L. REV. 295

(2013); Jeffrey J.R. Sundram, Comment, The Downside of Success: How Increased

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1031

broadens the pay-for-play theme of this perennial critique by suggesting that

employee status for college football players would allow them to form a union and

bargain over safety policies related to COVID-19 infections and long-term health

effects arising from this virus.

To measure the differences between pro and college football procedures, I

broke down the NFL’s seventy-two-page COVID-19 agreement into six categories:

(1) symptom screening,

7

(2) COVID-19 testing,

8

(3) exposure and positive test

policies,

9

(4) quarantining,

10

(5) returning to athletic activity,

11

and (6) contact

tracing.

12

I broke these elements into forty-five points. I created a scorecard for each

Power 5 school that replied with usable information. I scored one point for each

school policy that matched an NFL policy.

My scoring system revealed gaps between pro and college football. The NFL

and Power 5 COVID-19 policies and practices were roughly similar for (1) symptom

identification and screening,

13

though the NFL had more stringent standards; (2)

isolation protocols for players who tested positive,

14

though the NFL implemented

additional precautions; (3) cardiac screening,

15

though the NFL specified a more

thorough process; and (4) policies for returning to practice and games,

16

with the

main similarity being a minimum ten-day period of isolation after a player registered

a positive test.

However, my study revealed significant differences between NFL and NCAA

COVID-19 policies and practices, including (1) criteria for high-risk NFL players,

which included individualized risk categories for the NFL but not college players;

17

(2) the NFL’s more protective protocols for high-risk players, with suggested

isolation and medical monitoring, essentially treating them like infected players;

18

(3) the frequency of COVID-19 testing, with some NCAA schools testing as little

as three times per week, compared to daily testing in the NFL;

19

and (4) contact

tracing in the NFL, enabled by wearable tracking equipment that measured player-

Commercialism Could Cost the NCAA Its Biggest Antitrust Defense, 85 TUL. L. REV. 543

(2010); Daniel E. Lazaroff, The NCAA in Its Second Century: Defender of Amateurism or

Antitrust Recidivist?, 86 OR. L. REV. 329 (2007); Robert A. McCormick & Amy Christian

McCormick, The Myth of the Student-Athlete: The College Athlete as Employee, 81 WASH.

L. REV. 71 (2006).

7

See infra note 122.

8

See infra Finding 3, Bullet Point 2; see also ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 26–27.

9

See infra Finding 3, Bullet Points 3–6; see also ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 60–61.

10

See infra Finding 4; see also ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 9.

11

See infra Finding 5; see also ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 26.

12

See infra Finding 7; see also ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 38.

13

See infra Finding 4, Bullet Point 2 (citing ADDENDUM, supra note 1).

14

See infra Finding 5, Bullet Point 4 (citing ADDENDUM, supra note 1).

15

See infra Finding 6, Bullet Point 2 (citing ADDENDUM, supra note 1).

16

See infra Finding 7.

17

See infra Finding 3, Bullet Points 1 & 4.

18

See infra Finding 5, Bullet Point 3.

19

See infra Finding 4.

1032 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

to-player contact on the field and during travel, compared to no policy for wearable

technology contact tracing in college football.

20

B. Organization of this Article

In Part II, I explain how NCAA football players are unable to form a union and

engage in collective bargaining.

21

Section II.A shows that college players cannot

bargain collectively with their schools because they are not considered employees,

a legal predicate under applicable labor laws.

22

Section II.B explores how NFL

players engage in bargaining over their pay and the terms and conditions of their

employment.

23

In contrast, as Section II.C shows, the NCAA limits player input to

a Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC), a captive group that compares to

“company unions” in the 1930s, which employers created to forestall union

representation.

24

Part III describes my research design and methods.

25

Section III.A applies the

concept of a natural experiment in sports economics to the concurrent development

of COVID-19 policies in union and nonunion football settings in 2020.

26

This

framework undergirds my research design, which compares pro football safety

policies that were collectively bargained for and similar policies imposed by schools

on college players.

27

Part IV presents my empirical findings.

28

In Section IV.A.1, I report the sample

characteristics in Finding 1.

29

Section IV.A.2 reports Findings 2–9 for COVID-19

testing policies.

30

The main elements of these findings relate to the checklist of

symptoms (Finding 2),

31

individualized risk assessment (Finding 3),

32

daily

screening for symptoms and COVID-19 testing (Finding 4),

33

quarantine testing and

medical monitoring (Finding 5),

34

cardiac testing (Finding 6),

35

criteria for return-

to-activity (Finding 7),

36

and contact tracing policies and technology (Finding 8).

37

20

See infra Finding 8, Bullet Points 2 & 3.

21

See infra Part II.

22

See infra Section II.A.

23

See infra Section II.B.

24

See infra Section II.C; infra notes 69–70 and accompanying text.

25

See infra Part III.

26

See infra Section III.A.

27

See infra Section III.B.

28

See infra Part IV.

29

See infra Section IV.A.1.

30

See infra Section IV.A.2.

31

See infra Table 2.

32

See infra Table 3.

33

See infra Table 4.

34

See infra Table 5.

35

See infra Table 6.

36

See infra Table 7.

37

See infra Table 8.

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1033

In Finding 9,

38

I pick out chronological milestones in this testing and treatment

sequence—essentially four key points in structuring prevention, treatment, and

mitigation. These findings provide an overall sense of the effectiveness of college

protocols as compared to the NFL-NFLPA procedures.

39

Section IV.A.3 compares

scheduling disruptions due to COVID-19 for college and NFL teams.

40

Following

this timeline, Finding 11 charts the weekly frequency of game postponements and

cancellations in college versus pro football.

41

Section IV.B enumerates caveats and

limitations in this study.

42

Part V offers conclusions.

43

My findings support studies that show the (A)

superiority of worker safety in unionized versus nonunion work settings,

44

(B)

prevalence of company unions long after the 1930s,

45

and (C) employment model as

a better way to classify Power 5 football players than as amateurs.

46

II. NCAA AND NFL PLAYERS: THE EMPLOYMENT BARRIER TO UNIONIZATION

College football players are not employees.

47

The NCAA classifies college

players as amateurs, meaning they fall outside the definition of an employee.

48

Thus,

38

See infra Table 9.

39

This refers to the collective bargaining agreement between the National Football

League and the National Football League Players Association, a labor union for professional

football players. These parties entered into the NFL-NFLPA COVID-19 PROTOCOLS FOR

2020 SEASON. ADDENDUM, supra note 1.

40

See infra Section IV.A.3.

41

See infra Table 11.

42

See infra Section IV.B.

43

See infra Part V.

44

See infra Section V.A.

45

See infra Section V.B.

46

See infra Section V.C.

47

The amateur student-athlete model was upheld recently in two appellate cases that

rejected NCAA player claims that they are employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

See Dawson v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 932 F.3d 905 (9th Cir. 2019); Berger v. Nat’l

Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 843 F.3d 285 (7th Cir. 2016). But see Livers v. Nat’l Collegiate

Athletic Ass’n, 2018 WL 3609839 (E.D. Pa. 2018) (denying the NCAA’s motion to dismiss).

48

The 2020–21 NCAA Division 1 Manual states as follows:

The purposes of this Association are: (a) To initiate, stimulate and improve

intercollegiate athletics programs for student-athletes and to promote and develop

educational leadership, physical fitness, athletics excellence and athletics

participation as a recreational pursuit; . . . [and] (c) To encourage its members to

adopt eligibility rules to comply with satisfactory standards of scholarship,

sportsmanship and amateurism . . . . A student-athlete may receive athletically

related financial aid administered by the institution without violating the principle

of amateurism, provided the amount does not exceed the cost of education

authorized by the Association; however, such aid as defined by the Association

shall not exceed the cost of attendance as published by each institution. Any other

1034 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

college players cannot form a union because collective bargaining laws such as the

National Labor Relations Act (NLRA),

49

Railway Labor Act,

50

and state collective

bargaining laws,

51

apply only to employees. Moreover, because the NLRA excludes

all public sector employment relationships, fifty-three of the sixty-five (81%) Power

5 football programs cannot engage in legally sanctioned collective bargaining—a

legal barrier that would moot the possibility of collective bargaining for college

football players unless special legislation were enacted for them.

52

financial assistance, except that received from one upon whom the student-athlete

is naturally or legally dependent, shall be prohibited unless specifically authorized

by the Association.

NAT’L COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASS’N, 2020–21 NCAA DIVISION I MANUAL, art. 1.2(a), (c)

[hereinafter 2020–21 NCAA MANUAL] (emphasis added).

49

Nat’l Lab. Rel’s. Act (NLRA), ch. 372, 49 Stat. 449 (1935) (codified as amended at

29 U.S.C. §§ 151–69 (2020)). The NLRA defines employee as “any employee . . . unless this

subchapter explicitly states otherwise.” Id. at § 152(3). The same section then excludes “any

individual employed by . . . any other person who is not an employer as herein defined.” Id.

The definition of an employer excludes “any State or political subdivision thereof. . . .” Id.

Thus, players at state universities would need collective bargaining laws in their states to

bargain with their schools over pay and conditions of employment.

An example of a state law that provides for public sector collective bargaining is CONN.

GEN. STATE. ANN., infra note 64. I propose a federal form of NCAA-specific collective

bargaining to address this fractured approach to private- and public-sector collective

bargaining. See infra notes 48, 185.

50

Ry. Lab. Act of 1926, ch. 347, § 1, 44 Stat. 577 (codified as amended at 45 U.S.C. §

151, Fifth (2020)) (defining an employee as “every person in the service of a carrier . . . who

performs any work defined as that of an employee or subordinate official in the orders of the

Surface Transportation Board now in effect”). The Railway Labor Act (RLA) is relevant to

my discussion of legislating a federal collective bargaining law that would apply only to

NCAA players. See infra note 190, and related discussion. The RLA and its jurisdiction over

carriers in rail and air transport is analogous to college athletics insofar as the law regulates

transport industries that are especially important to the nation’s economy.

51

E.g., Illinois Educational Labor Relations Act (IELRA), 115 ILL. COMP. STAT. ANN.

5/1–5/21. The IELRA defines an “employee” broadly to include “any individual, excluding

supervisors, managerial, confidential, short term employees, student, and part-time academic

employees of community colleges employed full or part time by an educational employer.”

Id. at 5/2(b) (including exceptions for managerial and confidential employees).

52

The remaining twelve of the sixty-five Power 5 conference schools are private

institutions: Baylor, Boston College, Duke, Northwestern, Notre Dame, Stanford, Syracuse,

TCU, University of Miami, USC, Vanderbilt, and Wake Forest. Notably, only a smattering

of states provide public-sector collective bargaining. If, for example, football players at

Illinois formed a union under the IELRA, this would leave conference schools without a

public sector collective bargaining law at a competitive disadvantage. Id. Wisconsin repealed

its collective bargaining law for virtually all public sector employees, and its action was

upheld in State ex rel. Ozanne v. Fitzgerald, 798 N.W.2d 436, 441 (Wis. 2011).

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1035

A. College Players Cannot Form a Labor Union Because They Are Not

Employees

The NCAA defines college sports as an activity pursued by “the student body”

that cannot be a part of “professional sports.”

53

This idyllic status has roots in the

nineteenth-century cultivation of athletic competition to foster Christian character.

54

The NCAA combines intercollegiate athletics with college degree programs by

strictly designating athletes as amateurs.

55

Over time, the NCAA has lost touch with

its culture of amateurism—for example, the NCAA continues to declare that college

sports are an “avocation.”

56

It believes that its educational mission transcends

53

The purpose of the NCAA is stated as follows:

The competitive athletics programs of member institutions are designed to be a

vital part of the educational system. A basic purpose of this Association is to

maintain intercollegiate athletics as an integral part of the educational program

and the athlete as an integral part of the student body and, by so doing, retain a

clear line of demarcation between intercollegiate athletics and professional sports.

2020–21 NCAA MANUAL, supra note 48, at 1.3.1.

54

Professor Karen L. Hartman states that:

In the mid-1800s to the early 1900s, sport became increasingly popular in

America. As technology and manufacturing developed, more and more

Americans turned toward sport as a way to fill their newfound leisure time. During

this time, there were several national organizations and important figures that

served to frame sport as a moral endeavor. Specifically, the Young Men’s

Christian Association (YMCA), the Muscular Christianity Movement, Bernarr

Macfadden and the Physical Culture magazine, Theodore Roosevelt, and the

creation of the National Collegiate Athletics Association worked together to

create an enduring myth of the athlete as a moral hero. People were exposed to

this message if they went to church, listened to a Presidential speech, or read a

magazine; these five factors infiltrated sport and morality into numerous aspects

of society. Modern sport, therefore, was incubated by practitioners of the social

gospel during Protestant Christianity’s time of optimistic missionary revival.

Karen L. Hartman, The Rhetorical Myth of the Athlete as a Moral Hero: The Implications of

Steroids in Sport and the Threatened Myth (2008) (Ph.D. dissertation, Louisiana State

University), https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3014&context=gra

dschool_dissertations [https://perma.cc/23SC-JK37]; See Justice v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic

Ass’n, 577 F. Supp. 356, 361 (D. Ariz. 1983) (quoting NCAA regulations from that time).

55

See Justice v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 577 F. Supp. 356, 361 (D. Ariz. 1983)

(quoting NCAA regulations from that time).

56

See Bloom v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 93 P.3d 621, 626 (Colo. App. 2004)

(“Student participation in intercollegiate athletics is an avocation, and student-athletes

should be protected from exploitation by professional and commercial enterprises.”)

(emphasis added) (quoting 2020–21 NCAA MANUAL, supra note 48, at art. 2.9)).

1036 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

commercialism.

57

A student crosses the amateur boundary by signing a contract to

play a professional sport.

58

Beginning in the 1950s, and as a result of football-related deaths and injuries,

college football players began to litigate their status as employees.

59

Some state

appellate courts in workers’ compensation cases viewed NCAA athletes as

employees.

60

However, this trend gave way to court rulings denying college athletes’

claims for workers’ compensation benefits.

61

In some instances, state legislation

resolved this ambiguity by excluding college athletes from the workers’

compensation insurance system.

62

More recently, NCAA athletes have sued under the Fair Labor Standards Act,

seeking a ruling that they are employees. So far, their efforts have failed. Two federal

appeals courts have ruled that the amateur student-athlete model precludes a court

from ruling that NCAA athletes are employees under the Fair Labor Standards Act.

63

The distinction between amateur and employee is crucial because the right to

form a union and engage in collective bargaining is limited to persons in an

employment relationship. Thus, for players at state universities and colleges, it is

significant that state laws providing public-sector collective bargaining rights are

57

See Banks v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 746 F. Supp. 850, 852 (N.D. Ind. 1990)

(stating that the NCAA organizes amateur intercollegiate athletics “as an integral part of the

educational program and . . . retain[s] a clear line of demarcation between intercollegiate

athletics and professional sports”).

58

Shelton v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 539 F.2d 1197, 1198 (9th Cir. 1976)

(referencing NCAA DIVISION I MANUAL § 12.1.2 (c)).

59

See, e.g., Univ. of Denver v. Nemeth, 257 P.2d 423, 428 (Colo. 1953) (ruling that a

student-athlete who hurt his back during the team’s football practice qualified as an employee

who was eligible for worker’s compensation benefits because he “engage[d] in football

games under penalty of losing the job and meals” and therefore “playing football was an

incident of his employment by the University”).

60

See, e.g., Van Horn v. Indus. Accident Comm’n, 33 Cal. Rptr. 169, 170–74 (Cal. Ct.

App. 1963) (holding that the widow and minor children of a student-athlete, who was killed

in a plane crash while returning from a game, were entitled to death benefits under the

California Workmen’s Compensation Act because athletic scholarship was “consideration

. . . paid for services”), superseded by statute, CAL. LAB. CODE § 3352(a)(11) (West 2018),

as recognized in Shephard v. Loyola Marymount Univ., 102 Cal. Rptr. 2d 829, 832–33 (Cal.

Ct. App. 2002).

61

See Rensing v. Ind. State Univ. Bd. of Trs., 444 N.E.2d 1170, 1174–75 (Ind. 1983);

State Comp. Ins. Fund v. Indus. Comm’n, 314 P.2d 288 (Colo. 1957) (holding that a student-

athlete who was fatally injured while playing in a college football game, was not entitled to

a beneficiary death benefit under the Colorado Workmen’s Compensation Act).

62

California excludes college players from worker’s compensation. CAL. LAB. CODE §

3352(a)(11) (West 2018) (excluding a student from the definition of “employee” if they

“participat[e] as an athlete in amateur sporting events sponsored by a . . . public or private

nonprofit college, university, or school, who does not receive remuneration for the

participation, other than the use of athletic equipment, uniforms, transportation, travel, meals,

lodgings, scholarships, grants-in-aid”).

63

See Dawson v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 932 F.3d 905 (9th Cir. 2019); Berger

v. Nat’l Collegiate Athletic Ass’n, 843 F.3d 285 (7th Cir. 2016).

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1037

predicated on an employment relationship.

64

More generally, the amateur status of

college athletes led to the futile outcome for football players at Northwestern

University who tried to form a union under the NLRA: The National Labor Relations

Board ended their organizing efforts by declining to assert jurisdiction over cases

involving grant-in-aid football players.

65

B. Collective Bargaining in Professional Sports

During the Great Depression, Congress enacted the National Industrial

Recovery Act (N.R.A.).

66

The law aimed to foster collective bargaining between

employers and labor unions.

67

However, the N.R.A. was a weak law: It allowed

collective bargaining without specifying conditions to require employers to

negotiate terms and conditions of employment with a labor organization.

68

Employers did not accept that employees should have an independent voice in their

workplace and instead formed company unions.

69

These employee groups were

64

E.g., CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. §§ 31–104.

65

See Nw. Univ. and Coll. Athletes Players Ass’n, 362 N.L.R.B. 1350 (2015).

66

Nat’l Indu. Recovery Act (NIRA), ch. 90, 48 Stat. 195 (1933), invalidated by A.L.A.

Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States, 295 U.S. 495, 551 (1935).

67

Edwin E. Witte states that:

[E]ssential provisions of this section—the affirmative recognition of the right of

workingmen to bargain collectively through representatives of their own choice

and the prohibition of interference by employers with the exercise of this right—

are but restatements of principles previously recognized in several acts of

Congress and, earliest of all, by the National War Labor Board during the World

War, when that board was the supreme authority upon industrial relations in a

large part of American industry.

See Edwin E. Witte, The Background of the Labor Provisions of the N.I.R.A., 1 U. CHI. L.

REV. 572, 573 (1934).

68

Laura J. Cooper expressed that:

Administration of the NIRA by the National Recovery Administration (NRA)

soon revealed the weaknesses of the articulated labor protections in Section 7(a).

Section 7(a) provided no enforcement powers or procedures for selection of

employee representatives. There was no specific list of prohibited employer

actions or requirement for employers to bargain with organizations that

represented their employees. Ambiguities in the Act could be interpreted to

sanction employer-controlled company unions, allow proportional rather than

exclusive representation, and permit individual rather than collective bargaining.

See Laura J. Cooper, Letting the Puppets Speak: Employee Voice in the Legislative History

of the Wagner Act, 94 MARQ. L. REV. 837, 840 (2011).

69

The Department of Labor’s exhaustive study of 14,725 workplaces summarized the

use of company unions by employers in this way:

1038 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

often illusory exercises in worker representation: companies wrote their bylaws and

set their agendas.

70

Sen. Robert Wagner addressed the failure of the N.R.A. to provide more legal

protection to collective bargaining by introducing the bill that became the National

Labor Relations Act (NLRA).

71

The goal of this Depression-era law, also called the

[T]heir establishment was most frequently due to the pressure of trade-union

activity . . . [and] were set up entirely by management. Management conceived

the idea, developed the plan, and initiated the organization . . . more than half [of

company unions] performed none of those functions which are usually embraced

under the term “collective bargaining.” Some of these were merely agencies for

discussion. Others had become essentially paper organizations after their primary

function was performed when the trade-union was beaten.

U.S. DEP’T. OF LAB., BUREAU LAB. STAT., CHARACTERISTICS OF COMPANY UNIONS 1935

BULL. 634 199–205 (1937).

70

General Motors’ Pontiac plan illustrates employer control of this participatory

process:

This provides for voluntary membership of all employees of the manufacturing

department; that is, voluntary for all employees 21 years or more, with at least 90

days of service and at least first papers. These employees choose their

representatives from among the members of their own division with at least one

year’s service. They meet alone, but the factory manager must be notified of all

meetings. Management is present only when requested. The meeting place is

established by the works council subject to the approval of the plant manager. The

company pays the representatives their regular earned rate, prints the ballots for

elections, and elections are held on company time. In addition, the company will

furnish a stenographer for any meeting on request.

The plan emphasizes that membership is voluntary, but it provides that only

members of the employees association have the right to make a complaint to the

works council with reference to wages, hours of labor, working conditions, or

other appropriate subjects. Only members have a right to take out insurance and

to participate in the company savings and investment plans.

. . . In other words, they offer an inducement to the workers to come into their

company union, and say that he cannot be a beneficiary under these plans

otherwise. . . . In cases of disagreement, appeal is possible all the way up to the

general management of the company, who, it is said, ‘will take up the subject for

consideration.’

To Create a Nat’l Lab. Bd.: Hearing on S. 2926 Before the S. Comm. on Educ. & Lab., 73d

Cong. 128 (1934) [hereinafter Nat’l Lab. Bd. Hearing] (statement of Mr. William Green,

Pres. of the Am. Fed’n of Lab).

71

See id. at 110. Referring to the hearing, Senator Robert Wagner emphasized that:

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1039

Wagner Act, was to give employees a voice in determining their wages and working

conditions.

72

This was to be achieved by providing employees equality of bargaining

power with employers.

73

Thus, the NLRA provided employees basic collective

bargaining rights—forming a union, bargaining with an employer, and engaging in

concerted activities.

74

The law spurred growth in union membership, which peaked in 1954 at 34.7%

of the non-agricultural workforce.

75

However, professional athletes did not engage

in collective bargaining with leagues until the 1960s.

76

In football, the players

association was involved in protracted antitrust lawsuits that challenged the NFL’s

anticompetitive labor market rules.

77

The players association also bargained over

Yesterday we had a hearing in the automobile industry and it came out very clearly

that the company union was formed by sending to each worker a constitution and

bylaws telling him, ‘This is now your organization.’ As the result of that an

election was held, and the workers testified that they voted because they knew

very well if they did not vote their jobs were gone.

Nat’l Lab. Bd. Hearing, supra note 70, at 110.

72

Senator Robert Wagner‘s vision when he introduced the bill that eventually became

the NLRA:

The law has long refused to recognize contracts secured through physical

compulsion or duress. The actualities of present-day life impel us to recognize

economic duress as well. We are forced to recognize the futility of pretending that

there is equality of freedom when a single workman, with only his job between

his family and ruin, sits down to draw a contract of employment with a

representative of a tremendous organization having thousands of workers at its

call. Thus the right to bargain collectively, guaranteed to labor by section 7(a) of

the Recovery Act, is a veritable charter of freedom of contract; without it there

would be slavery by contract.

See 78 Cong. Rec. S3678–20 (daily ed. March 5, 1934) (statement by Sen. Robert Wagner).

73

Id.

74

Section 7 of the Act provides: “Employees shall have the right to self-organization,

to form, join, or assist labor organizations, to bargain collectively through representatives of

their own choosing, and to engage in other concerted activities . . . .” 29 U.S.C. § 157 (2019).

75

DEP’T. OF LAB., BUREAU LAB. STATS., BULL. NO. 2070, HANDBOOK OF LAB. STAT.

412 tbl. 165, col. 7 (1980).

76

Baseball was the first sport to enter into collective bargaining. See Marvin Miller:

Founding Executive Director, 1966–1982, MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL PLAYERS,

https://www.mlbplayers.com/marvin-miller [https://perma.cc/Y3VP-B6UD] (last visited

July 9, 2021) (“In 1968, Miller led a committee of players that negotiated the first collective

bargaining agreement in the history of professional sports.”).

77

Mackey v. NFL, 543 F.2d 606, 620–21 (8th Cir. 1976) (finding that the “Rozelle

Rule”—which required a team acquiring a free-agent to compensate the former team—

constituted an anti-trust violation under the Sherman Act). The opinion also noted that

football players entered into formal labor agreements, the first ran from July 15, 1968, to

February 1, 1970. Id. at 610.

1040 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

other issues, including a player’s right to file a grievance related to their injuries.

78

When a Minnesota Vikings offensive lineman, Korey Stringer, died from heat-

related medical conditions in training camp in 2001,

79

the NFL and NFLPA labor

agreement had several provisions concerning player safety.

80

Another lawsuit, filed

by retired players in 2011, alleged that the collective bargaining agreement (CBA)

did not address the NFL’s duty to warn players about the long-term effects of

concussions.

81

Players eventually settled for a brain-injury fund valued at $1

billion.

82

When the NFL and players association negotiated a new CBA in 2020,

their contracts included many provisions for player safety and medical care.

83

A

short time later, they bargained for an addendum regarding COVID-19 protocols.

84

78

NFL Mgmt. Council v. Superior Ct., 338 (Cal. Ct. App. 1983) (describing a player’s

use of an “injury grievance” provision under the collective bargaining agreement between

the NFL Players Association and the management council).

79

Stringer v. NFL, 474 F. Supp. 2d 894, 898 (S.D. Ohio 2007) (bringing a wrongful

death action against the NFL, Minnesota Vikings, and Riddell, an equipment maker). A key

part of this case against the NFL related to the league’s hot weather guidelines and protocols

for treating heat-related illnesses, which the plaintiff argued were negligent and not covered

by the CBA to avoid preemption issues. Id. at 904–05, 907. The court ruled that several

claims against the NFL and Riddell were not preempted by section 301 of the Labor-

Management Relations Act because the labor agreement did not relate to those matters, and

denied motions to dismiss these claims. Id. at 915.

80

Id. at 905–06 (referencing Art. XIII, § 1(a) of the CBA) (discussing a player’s right

to medical treatment and describing a Joint Committee on Player Safety and Welfare “to

discuss player safety and welfare aspects of playing equipment, playing surfaces, stadium

facilities, playing rules, [and] player-coach relationships”).

81

In re NFL Players Concussion Inj. Litig., 821 F.3d 410, 421–22 (3d Cir. 2016).

82

Id. at 440, 444 (affirming settlement which “provide[s] nearly $1 billion in value to

the class of retired players”).

83

NFLPA, COLLECTIVE BARGAINING AGREEMENT 213 (2020), https://nflpaweb.blob.

core.windows.net/website/PDFs/CBA/March-15-2020-NFL-NFLPA-Collective-Bargaining

-Agreement-Final-Executed-Copy.pdf [https://perma.cc/Q8SC-6J4S]. Article 39 contains

more than twenty sections, including: Physicians, Trainers, the NFLPA’s Medical Director,

Emergency Action Plan, Accountability and Care Committee, Player’s Right to a Second

Medical Opinion, Player’s Right to a Surgeon of His Choice, Preseason Physical, Substance

Abuse and Performance-Enhancing Substances, Visiting Team Locker Rooms, Field Surface

Safety & Performance Committee, Joint Engineering, and Equipment Safety Committee,

Sleep Studies, Club-Wide Biospecimen Collection, Head, Neck, and Spine Committee’s

Concussion Diagnosis and Management Protocol, Game Concussion Protocol Enforcement,

Player Scientific and Medical Research Protocol, Behavioral Health Program, Prescription

Medication and Pain Management Program, and Remedies. Id. at i–xv.

84

The main provisions of this lengthy agreement are discussed infra, in Part IV.

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1041

C. NCAA Student-Athlete Advisory Committees: A Company Union for College

Players

The NCAA provides college players with representation that resembles

company unions in the 1930s. The NCAA adopted this controlled form of

participation by establishing Student-Athlete Advisory Committees (SAACs) in

1989.

85

Like company unions, the NCAA gave SAACs limited functions. SAACs

were “formed primarily to review and offer student-athlete input on NCAA activities

and proposed legislation that affected student-athlete welfare.”

86

SAACs have no

actual power or defined authority. Instead, they “[g]enerate a student-athlete voice

within the NCAA structure,” “[s]olicit student-athlete response to proposed NCAA

legislation,” “[r]ecommend potential NCAA legislation,” “[r]eview, react and

comment to the governance structure on legislation, activities and subjects of

interest,” “[a]ctively participate in the administrative process of athletics programs

and the NCAA,” and “[p]romote a positive student-athlete image.”

87

Minutes of the

quarterly meetings of the Division I SAAC reveal the group’s absence in developing

COVID-19 safety policies.

88

85

NCAA, NCAA Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, (1989) http://www.ncaapublic

ations.com/productdownloads/SAAC02.pdf [https://perma.cc/47A6-YXJM].

86

Id.

87

NCAA, NCAA Student-Athlete Advisory Committees (SAACs), http://www.ncaa.org/

student-athletes/ncaa-student-athlete-advisory-committees-saacs#:~:text=Each%20committ

ee%20is%20made%20up,%2Dathletes'%20lives%20on%20campus [https://perma.cc/KW

C5-UKP9] (last visited July 18, 2021).

88

NCAA, Report of the NCAA Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (Apr.

22, 2020), https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/committees/d1/saac/Apr2020D1SAAC_

Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/VVL9-MRKV] (listing no action items on the agenda and only

informational points, including an update from the NCAA research staff on the NCAA

Student-Athlete COVID-19 Well-Being Survey). By mid-summer, as football programs

began workouts, some schools required players to sign COVID-related waivers. See, e.g.,

Ross Dellenger, Coronavirus Liability Waivers Raise Questions as College Athletes Return

to Campus, SPORTS ILLUSTRATED (June 17, 2020), https://www.si.com/college/2020/06/17/

college-athletes-coronavirus-waivers-ohio-state-smu [https://perma.cc/HH9U-JSKH]

(reporting that returning athletes, “without legal representation, are agreeing to waive their

legal rights”). However, when SAAC met on July 17, 2020, in a videoconference, and

developed priorities for the 2020–21 year, they barely discussed COVID-19. In Point 8,

during the discussion part of the meeting for conference reports, COVID-19 was mentioned

only once, and it was framed with other items, including social justice and mental health

concerns for student-athletes. NCAA, Report of the NCAA Division I Student-Athlete

Advisory Committee (July 17, 2020), https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/committees/d1/sa

ac/July2020D1SAAC_Report.pdf. [https://perma.cc/GC9F-G2XJ]. SAAC held a meeting in

mid-August and “provided feedback related to the 2020 fall playing season and agreed that

student-athletes need clear guidance before the Division can adopt a comprehensive playing

season model for the remainder of the fall.” NCAA, Report of the NCAA Division I Student-

Athlete Advisory Committee (Aug. 18, 2020), https://ncaaorg.s3.amazonaws.com/commit

1042 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

The bylaws of a campus-level SAAC confirm that these groups function like

company unions. Northwestern University—the school involved in the most serious

effort by football players to form a union under the NLRA

89

—has a SAAC.

90

However, the campus SAAC does not post its bylaws on a public access website.

Stanford University also has a SAAC, and like Northwestern, its football team plays

in a Power 5 Conference. Unlike Northwestern, Stanford’s SAAC publishes its

bylaws.

91

However, the group’s modest advisory functions fall short of bargaining

over wages, hours of practice, and other conditions of their athletic participation.

92

III. RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHODS

A. Research Design: A Natural Experiment

When the COVID-19 pandemic escalated in March 2020, the impact on

professional and NCAA sports was abrupt and severe, with shutdowns occurring

between March 11–12.

93

Football was the best positioned of team sports to adjust to

tees/d1/saac/Aug2020D1SAAC_Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/DDT9-YSE5]. Nothing in the

minutes specifically referenced COVID-19. In October, SAAC discussed COVID-19 in the

limited context of reviewing a draft policy, “Competition Waivers and Extensions of

Eligibility for Winter and Spring Sport Student-Athletes.” NCAA, Report of the NCAA

Division I Student-Athlete Advisory Committee, (Oct. 22, 2020), https://ncaaorg.s3.amazon

aws.com/committees/d1/saac/Oct2020D1SAAC_Report.pdf [https://perma.cc/MSZ7-

7BFJ]. This dealt with player eligibility, not safety related to COVID-19.

89

See Nw. Univ. and Coll. Athletes Players Ass’n, 362 N.L.R.B. 1350 (2015).

90

Nw. Univ., Student-Athlete Advisory Committee (SAAC), NW. ATHLETICS (2021),

https://nusports.com/sports/2015/3/18/GEN_2014010134.aspx [https://perma.cc/9K4Q-

GP4C] (last visited Jan. 16, 2021).

91

Stanford Univ., Stanford SAAC, https://docs.google.com/document/d/1YG8_gQ6Q

nuvXfMctyfTLYoT_GT0jBaL6yx89X2XJTNY/edit?ts=5bede5cc#heading=h.w9jwwqv8m

2c0 [https://perma.cc/Y3GJ-4V42] (last visited July 9, 2021).

92

Id. at Art. II. Mission. The Stanford University Student-Athlete Advisory Committee

mission states:

Goals and Commitments of SAAC are to help student-athletes:

• Achieve elite-level athletic performance

• Achieve academic excellence

• Participate in community service

• Foster lasting relationships with alumni and faculty

• Develop leadership skills

Stanford Univ., supra note 91, at Art. II.

93

Scott Cacciola & Sopan Deb, N.B.A. Suspends Season After Player Tests Positive for

Coronavirus, N.Y. TIMES (Mar. 11, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/11/sports/bas

ketball/nba-season-suspended-coronavirus.html [https://perma.cc/D5TN-B84Z] (reporting

that the NBA abruptly canceled games and suspended the season due to the first player

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1043

the pandemic because the first wave of lockdowns occurred near the start of their

off-seasons.

94

The NFL and NCAA had approximately five months to decide

whether to play a 2020 season and what safety protocols to use.

My research design utilizes a natural experiment. A sports economics study,

“A Natural Experiment to Determine the Crowd Effect Upon Home Court

Advantage,”

95

offers a model for this design. In the study, the researchers tested for

the independent effect of a supportive crowd on a team’s performance. From 1999–

2014, the Los Angeles Clippers and Los Angeles Lakers shared the same home

facility, the Staples Center.

96

They also played four games against each other in this

arena, alternating as home and away teams.

97

As a home team, each team filled the

arena with its fans. This provided a natural experiment, allowing researchers to

measure the independent effect of a sympathetic home crowd on team performance.

The Clippers won 13 of 30 games (43.3%) against the Lakers when designated as

the home team, compared to winning 7 of 29 games (24.1%) as the visitors.

98

In

other words, the home crowd correlated with winning more games.

99

Professional and college football are sufficiently similar to offer a natural

experiment to determine whether collective bargaining has an independent effect on

player health protocols. Their games are on the same length and type of field, eleven

players are on offense, eleven players are on defense, a line of scrimmage is used to

testing positive for COVID-19); Greta Anderson, Coronavirus Looms Over March Madness,

INSIDE HIGHER ED (Mar. 5, 2020), https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2020/03/05/first-

ncaa-games-canceled-due-coronavirus [https://perma.cc/2Y8H-6UVF] (stating that two

colleges canceled basketball games due to COVID-19 outbreak on West Coast, putting

March Madness tournament at risk); NHL to Pause Season Due to Coronavirus, NHL (Mar.

11, 2020), https://www.nhl.com/news/nhl-coronavirus-to-provide-update-on-concerns/c-

316131734 [https://perma.cc/23WM-MXGZ] (declaring that hockey season paused until

further notice); Jabari Young, MLB Will Delay Opening Day by at Least Two Weeks, Spring

Training Canceled Due to Coronavirus, CNBC (Mar. 12, 2020, 4:41PM),

https://www.cnbc.com/2020/03/12/mlb-to-suspend-all-operations-spring-training-due-to-

coronavirus.html [https://perma.cc/YMR4-VFU7].

94

Ken Belson, N.F.L. Players Vote Yes on New 10-Year Labor Deal, N.Y. TIMES (Mar.

15, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/sports/football/nfl-cba-approved.html

[ttps://perma.cc/3H9A-TGGX] (reporting that the NFLPA approved a new, ten-year

collective bargaining agreement by a slim majority). While other pro and college sports

postponed or canceled games, the NFL experienced a more muted impact: “Given the

limitations on travel because of the risk of spreading coronavirus, teams will have to evaluate

players by telephone or video conference. This includes college players that teams want to

speak with before the draft, which is currently set to begin on April 23.” Id.

95

See generally Christopher J. Boudreaux, Shane D. Sanders & Bhavneet Walia, A

Natural Experiment to Determine the Crowd Effect Upon Home Court Advantage, 18 J.

SPORTS ECON. 737 (2017).

96

Id. at 740.

97

Id. (reporting that the teams played each other four times per season—except for the

2011 season, which had a lockout—with each team serving as the home team in two games).

98

Id.

99

Id. at 746.

1044 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

start most plays—bringing many players within six feet of each other—offensive

and defensive positions are the same, and games are played in four fifteen-minute

quarters that yield an hour of competition. The close similarity is borne out by the

fact that the NFL’s labor market is drawn almost entirely from the NCAA.

100

More

than 80% of rookie players drafted by an NFL team in 2020 made an NFL roster,

underscoring the close similarity of playing conditions in college and pro football.

101

The racial compositions of NFL and NCAA Power 5 rosters are also similar.

102

In 2019, Division I football had 3,671 Black players (46.1% of the total for all

teams), 2,935 (36.9%) white players, and 1,355 “Other” race players (17%).

103

In

2016, an analysis of pro football rosters concluded that the “NFL as a whole is about

68% black, although that number could be a couple [of] percent higher from the

unknowns. Black and Pacific Islander players are hugely overrepresented compared

to the American population, while all other races are heavily underrepresented.”

104

These statistics—apart from indicating similar compositions by race—also suggest

that NCAA and NFL players should have especially stringent safety conditions

because Black and other non-white people are more at risk for COVID-19

infections

105

and death.

106

100

See Scott Kacsmar, Where Does NFL Talent Come From?, BLEACHER REP’T (May

16, 2013), https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1641528-where-does-nfl-talent-come-from

[https://perma.cc/P4EW-B787] (analyzing rosters from the 2012 season, including practice

squads, from Pro-Football-Reference for all teams, a total of 1,947 players attended 256

different colleges; the study reports that only “seven players did not go to a college in the

United States”).

101

Rick Gosselin, Could the 2020 NFL Draft Be One of the Greatest?, FANNATION,

SPORTS ILLUSTRATED (Sept. 18, 2020), https://www.si.com/nfl/talkoffame/nfl/2020-nfl-

draft-produced-a-record-number-of-players-and-starters [https://perma.cc/6ACW-U9PA]

(“Of the 255 players selected last April, a record 209 of them made opening-day rosters.

That’s a success rate of 81.9 percent, another record for drafts.”).

102

See Michael Gertz, NFL Census 2016, PROFOOTBALLLOGIC (Apr. 19, 2017),

http://www.profootballlogic.com/articles/nfl-census-2016/ [https://perma.cc/JH5S-N3XZ];

see also Diversity Research: NCAA Race and Gender Demographics Database, NCAA,

[hereinafter NCAA] https://www.ncaa.org/about/resources/research/diversity-research

[https://perma.cc/M2CQ-DV6T] (last visited July 19, 2021).

103

NCAA, supra note 102.

104

Gertz, supra note 102.

105

See Shirley Sze, Daniel Pan, Clareece R. Nevill, Laura J. Gray, Christopher A.

Martin, Joshua Nazareth, Jatinder S. Minhas, Pip Divall, Kamlesh Khunti, Keith R. Abrams,

Laura B. Nellums & Manish Pareek, Ethnicity and Clinical Outcomes in COVID-19: A

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, LANCET, ECLINICAL MED. (Nov. 12, 2020),

https://www.thelancet.com/journals/eclinm/article/PIIS2589-5370(20)30374-6/fulltext

[https://perma.cc/2X9P-XX54] (finding an analysis of 18,728,893 patients from 50 studies

showed that Black and Asian patients had a higher risk of COVID-19 infection compared to

white patients).

106

See Michael Doumas, Dimitrios Patoulias, Alexandra Katsimardou, Konstantinos

Stavropoulos, Konstantinos Imprialos & Asterios Karagiannis, COVID19 and Increased

Mortality in African Americans: Socioeconomic Differences or Does the Renin Angiotensin

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1045

In sum, many important variables were essentially constant across the NFL and

NCAA Power 5 football platforms for the pandemic season of 2020. One significant

difference, however, was the process for implementing safety protocols related to

practices and games. In the fall of 2020, the NFL and NFLPA agreed to a seventy-

two-page addendum that addressed COVID-19 protocols.

107

In contrast, the NCAA

had no players association, its SAAC played no role in co-determining COVID-19

safety policies,

108

and even the Power 5 conferences had chaotic and disjointed

responses to resuming the 2020 season.

109

These disparate conditions for the NFL

and Power 5 football created a natural experiment to compare whether collective

bargaining produced worse, the same, or better safety protocols as opposed to a

nonunion process.

This was not an ideal natural experiment because factors other than collective

bargaining probably led to differences in COVID-19 protocols. The NFL’s protocols

reportedly cost teams $40 million.

110

Cost data for NCAA football COVID-19 safety

protocols were not reported but were probably less due to athletic budgets that

strained to support non-revenue sports.

111

System Also Contribute?, 34 J. HUM. HYPERTENSION 764 (July 15, 2020) (“African-

Americans suffer from a 2.4 and 2.2 times higher mortality rate when compared to [w]hites

and Asians or Latinos, respectively.”).

107

See ADDENDUM, supra note 1.

108

See id. (providing no indication that the NCAA was involved in determining

COVID-19 policies for the NFL); see also supra Section II.C.

109

See e.g., Paula Lavigne & Mark Schlabach, Nearly Half of Power 5 Won’t Disclose

COVID-19 Test Data, ESPN (Sept. 3, 2020), https://www.espn.com/college-

sports/story/_/id/29745712/nearly-half-power-5-disclose-covid-19-test-data [https://perma.

cc/3Y2S-TXRH]; Mark Kreidler, Coronavirus Is Placing College Sports on Hold, Putting

Students, University Budgets, and Entire Towns at Risk, TIME (Aug. 3, 2020, 8:00 AM EDT),

https://time.com/5874483/college-football-coronavirus/ [https://perma.cc/HK9M-RTJU];

Michael Rosenberg, It Took a Pandemic to See the Distorted State of College Sports, SPORTS

ILLUSTRATED (Dec. 29, 2020), https://www.si.com/college/2020/12/29/global-pandemic-

exposed-ncaa-inc [https://perma.cc/48W2-TXR4].

110

Gregg Bell & Lauren Kirschman, The Seahawks Are Perfect Against COVID, But

the Huskies Got Crushed — What Happened?, NEWS TRIB. (Dec. 19, 2020) (reporting that

the Seattle Seahawks spent about $40 million on daily PCR “gold standard” COVID-19

testing, at about $30 per test, while the nearby University of Washington spent about $21 to

$23 per test for antigen testing).

111

Id. (reporting that, because NCAA football rosters are larger than those for NFL

teams, the University of Washington routinely administered several dozen more COVID-19

tests than the Seattle Seahawks, driving up costs). The Seahawks also had more financial

backing to administer its COVID-19 program, with annual TV revenue of about $260

million. Id. In contrast, the Washington athletic program—presumably, like other Power 5

schools—faced a large hole in its budget from COVID-19 and had to administer its protocols

in the face of budget cuts. Id. This report did not mention, however, if the University of

Washington paid for some or all COVID-19 testing out of a general campus budget—a

possibility if the general student population was being tested with some regularity. Id. See

also Craig Garthwaite & Matthew J. Notowidigdo, The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Revealing

1046 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

Also, NCAA players were students on college campuses. NCAA programs

could not control their social interactions as much as NFL teams could restrict

players. By comparison, once NFL football players left practice- and game-related

activities, they were often subject to strongly normative guidelines to reduce social

interactions.

112

Also, unlike the NFL, NCAA football protocols were part of

comprehensive policies for other sports. In sum, these outside factors affected the

natural experiment for assessing an effect for collective bargaining. However, no

outside factor appeared to match the singular difference in the processes that the

NFL and Power 5 schools used to implement COVID-19 safety procedures.

B. Research Methods: Comparing NFL and Collegiate COVID-19 Protocols

On September 5, 2020, the NFL and NFLPA agreed to comprehensive COVID-

19 protocols. The addendum was posted online. I began by reading the addendum

and breaking out provisions for player safety.

113

These fell into six categories and

were subdivided into forty-five points. Based on these points, I created a scorecard

to compare with college protocols.

The start of the college football season was more irregular. Among Power 5

conferences, the Big 10 initially announced that it would significantly delay the start

of its 2020 football season.

114

Other conferences went forward with scheduling

games for the regular season. Facing pressure from President Donald Trump

115

and

the Regressive Business Model of College Sports, BROOKINGS BROWN CTR. CHALKBOARD

(Oct. 16, 2020) (reporting that low-revenue sports were being eliminated due to budget

strains caused by the COVID-19 pandemic).

112

Some provisions related to non-players, such as travel and media groups.

ADDENDUM, supra note 1, at 7 (Tier 2M (pool media) and Tier 3 (facility workers who do

not have close contact with players and coaches)).

113

See infra notes 126–28, 131–33.

114

Bruce Schoenfeld, Was the College Football Season Worth It?, N.Y. TIMES (Dec.

30, 2020), https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/30/magazine/college-football-pandemic.html

[https://perma.cc/QEX2-UD7W].

115

Allan Smith & Peter Alexander, Trump Takes Victory Lap Over Return of Big Ten

Football. College President Says it Has Nothing to Do with Him, NBCNEWS.COM (Sept. 16,

2020, 5:41 PM MDT), https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/donald-trump/trump-takes-

victory-lap-return-big-10-football-college-president-n124 [https://perma.cc/NK7F-95EQ]

(reporting on a late-August tweet by President Trump: “No, I want Big 10, and all other

football, back – NOW”). In a follow-up, President Trump tweeted, “Disgraceful that Big 10

is not playing football. Let them PLAY!” Id.

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1047

coaches

116

to put on a football season during the fall, the Big 10 modified its original

decision.

117

By the end of September, with a football season in place for Power 5

conferences, I began to identify FOIA and similar open records laws for the fifty-

three public schools in these conferences. I expected that the public schools would

respond to my request in whole or in large part because public records laws apply to

state-supported schools. (My survey confirmed this assumption: I received

numerous initial responses to my inquiries referencing a school’s obligations under

a public records law.)

118

These laws generally allow public access to a school’s

records, with exceptions.

119

I tempered my hope for cooperation from schools when

116

See, e.g., Orion Sang, Michigan Football Coach Jim Harbaugh Attends Protest,

Says ‘Free the Big 10,’ DETROIT FREE PRESS (Sept. 5, 2020, 3:59 PM ET),

https://www.freep.com/story/sports/college/university-michigan/wolverines/2020/09/05/

michigan-football-jim-harbaugh-protest/5730035002/ [https://perma.cc/287B-NA46]; Gabe

Lacques, 20 for 2020: Sports Figures Who Defined Courageous and Kind, Selfish and

Stubborn, USA TODAY (Dec. 28, 2020, 12:47 PM ET),

https://www.usatoday.com/story/sports/2020/12/28/2020-year-review-20-sports-figures-

defined-best-and-worst/4015133001/ [https://perma.cc/C4QP-BFL9] (explaining that while

the Big 10 was deliberating whether to play football in 2020, Nebraska Head Coach Scott

Frost suggested that his program would play a non-Big 10 schedule if games were canceled).

117

Schoenfeld, supra note 114.

118

See, e.g., Email from Melissa Tindell, Dir. of Commc’n, Univ. of Tenn. to Michael

H. Leroy, Professor, Univ. of Ill. Coll. of Law (Oct. 16, 2020) (on file with author) (“[O]nly

citizens of Tennessee may inspect and receive copies of public records under the Tennessee

Public Records Act. Tenn. Code Ann. § 10-7-503(a)(2)(A). It appears this law would impact

your request for information.”); see also Email from Bob Taylor, Open Records Man., Univ.

of Ga. to Michael H. Leroy, Professor, Univ. of Ill. Col. of Law (on file with author) (Oct.

22, 2020) (“Professor LeRoy—This is to acknowledge receipt of your October 16, 2020,

request for documents under the Georgia Open Records Act, and is in accordance with the

three-day period of response pursuant to O.C.G.A. § 50-18-71(b)(2).”).

119

See, e.g., 5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 140/1-11. The statute’s purpose states:

Pursuant to the fundamental philosophy of the American constitutional form of

government, it is declared to be the public policy of the State of Illinois that all

persons are entitled to full and complete information regarding the affairs of

government and the official acts and policies of those who represent them as

public officials and public employees consistent with the terms of this Act. Such

access is necessary to enable the people to fulfill their duties of discussing public

issues fully and freely, making informed political judgments and monitoring

government to ensure that it is being conducted in the public interest.

5 Ill. Comp. Stat. 140/1-11. The law also provides exceptions, stating that it “is not intended

to be used to violate individual privacy, nor for the purpose of furthering a commercial

enterprise, or to disrupt the duly-undertaken work of any public body independent of the

fulfillment of any of the fore-mentioned rights of the people to access . . . information.” Id.

1048 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

an investigative report found that college athletic departments concealed

information about COVID-19 infections from their communities.

120

Often, I was required to register online with these public universities to request

information. I devised a simple request for COVID-19 policies related to football

players. I avoided questions that would likely be rejected—for example, data on

testing results or player information. I also avoided requests that could be rejected

on the grounds of being burdensome or costly. I sent requests to all fifty-three public

schools and the legal departments of the twelve private schools

121

between October

15 and October 30, 2020. My request was the same for every school:

This request is for my research study, “COVID-19 Protocols for NCAA

Football and the NFL.” My survey includes all NCAA Power 5 conference

institutions, including those that are not subject to a FOIA or public

information disclosure law.

I respectfully request policies and procedures at your university relating to

(1) questionnaires, or similar inquiries, for football student-athletes for

COVID-19 symptoms and exposure to the virus; (2) criteria to identify

high-risk football student-athletes, and specialized procedures for them;

(3) screening and testing procedures for football student-athletes; (4)

screening and testing procedures for football student-athletes who test

positive or are symptomatic for COVID-19; (5) criteria to return football

student-athletes who test positive or are symptomatic for COVID-19 to

regular athletic activities; and (6) contact tracing policies and procedures

120

Blinder, Higgins, and Guggenheim states as follows:

At least 6,629 people who play and work in athletic departments that compete in

college football’s premier leagues have contracted the virus; the actual tally of

cases during the pandemic is assuredly far larger than what is shown by The

Times’s count, the most comprehensive public measure of the virus in college

sports.

See Blinder et al., supra note 3; see also id. (stating that the schools not named in the article’s

list, “many of them public institutions, released no statistics or limited information about

their athletic departments, or they stopped providing data just ahead of football season. This

had the effect of drawing a curtain of secrecy around college sports during the gravest public

health crisis in the United States in a century”).

121

Arranged by conferences in 2020, schools included ACC (Clemson, Florida State,

Georgia Tech, Louisville, North Carolina State, North Carolina, Pittsburgh, Virginia,

Virginia Tech); Big 10 (Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Maryland, Michigan, Michigan State,

Minnesota, Nebraska, Ohio State, Penn State, Purdue, Rutgers, and Wisconsin); Big Twelve

(Iowa State, Kansas, Kansas State, Oklahoma, Oklahoma State, Texas, Texas Tech, and West

Virginia); PAC-12 (Arizona, Arizona State, Cal (California-Berkeley), Colorado, Oregon,

Oregon State, UCLA, Washington, and Washington State); and SEC (Alabama, Arkansas,

Auburn, Florida, Georgia, Kentucky, LSU, Mississippi, Mississippi State, Missouri, South

Carolina, Tennessee, and Texas A&M).

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1049

for football student-athletes who test positive or are symptomatic for

COVID-19.

My request is only for football policies and procedures. If this information

is grouped with other sports, I would accept that more general information.

I prefer an email response with a PDF attachment over physical copies of

pages sent by mail. My email address is [email protected].

I am not seeking data or information relating to football student-athletes.

My research will also report institutions that do not participate in this

survey. If you wish to discuss my request, please email me. Thank you for

your time and cooperation.

I tracked responses and non-responses to my requests. The responses I received

sub-divided into fully or mostly complete information, partial information, and too

little information to be usable. Other schools informed me that their state’s FOIA

laws exempted requests from non-residents. Penn State noted that the university is

entirely exempt from all FOIA requests. Some schools delayed their response, often

several times. Other schools—especially private schools—never replied to me.

When a response was sufficient to be considered comprehensive, I tallied points

that matched items on the NFL-NFLPA scorecard. I assigned one point to each

matching item. While some points were probably more important than others in

limiting the spread of medical effects from COVID-19, I had no scientific basis for

assigning different weights to these points.

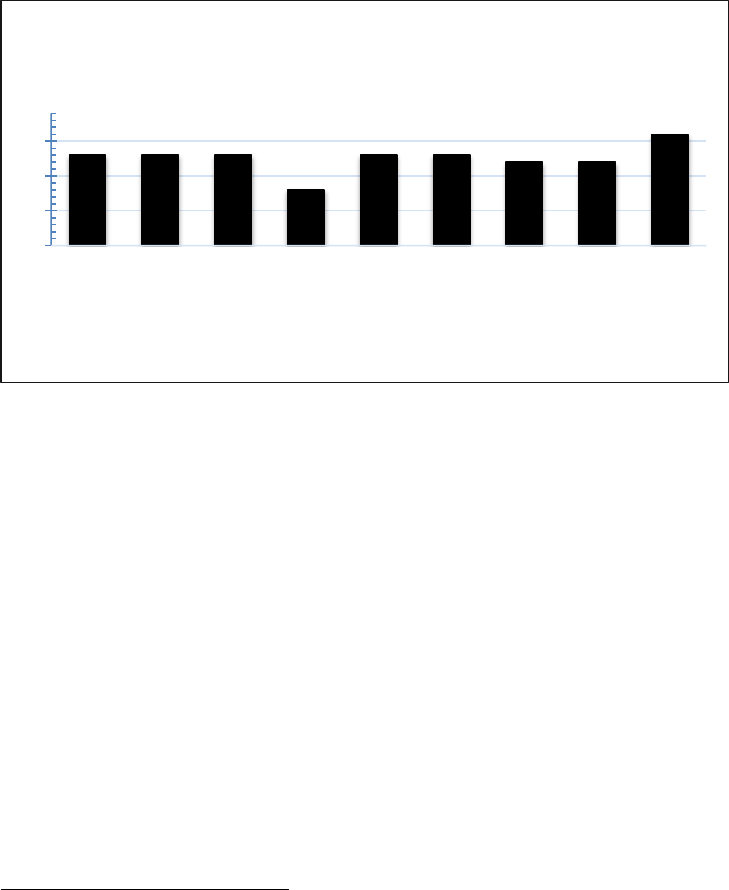

IV. EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

I present the empirical results in three parts. Section IV.A.1 pertains to school

responses and non-responses. In Section IV.A.2, I provide a statistical breakdown

of the usable responses. My scoring compared forty-five specific elements in the

NFL-NFLPA agreement with the policy materials that each school provided me. My

results show that schools scored between ten and thirty points. In Section IV.A.3, I

compare the number of Power 5 and NFL games postponed or canceled due to

COVID-19.

In Section IV.B, I interpret my results. The data have several limitations. I,

therefore, caution against making critical judgments of schools with lower scores. I

also note that as the 2020 football season continued, the NFL and NFLPA revised

their policies. Near the end of the 2020 football season, some Power 5 schools made

changes, too, such as adopting the use of KINEXON tracking technology,

122

a

protocol that was absent from the policies in my survey.

122

See, e.g., PAC-12 Sports, PAC-12 to Utilize KINEXON SafeZone for Rapid, Reliable

Tracing, 247 SPORTS (Nov. 30, 2020), https://247sports.com/college/washington/Article/

1050 UTAH LAW REVIEW [NO. 5

A. Survey Responses

1. Sample and Response Rate

Table 1 summarizes responses and non-responses from sixty-five Power 5

schools.

Table 1

Responses to FOIA and Open Records Requests by Power 5 Schools

No Response/Delayed Response (39 Schools)

Responses (26 Schools)

(Numbers in parentheses reflect games postponed or canceled)

No Response

Private: Boston College (1), Duke

(2), Miami (4), Notre Dame (1),

Northwestern (1), TCU (0),

Stanford (1), Syracuse (0), USC

(2), Wake Forest (6), Vanderbilt

(4) (21 disrupted games)

Public: Auburn (1), Florida (2),

Kansas State (0), Mississippi (0),

Wisconsin (3), North Carolina

State (1), Oklahoma (2),

Oklahoma State (1), Oregon State

(0), Purdue (3), South Carolina

(0), Texas Tech (0), Washington

State (3) (16 disrupted games)

Response Received: School Is

Exempt from Disclosure Law

Alabama (2), Arkansas (2), LSU

(3), Penn State (0), Pitt (1),

Tennessee (2), Virginia (4),

Virginia Tech (2) (16 disrupted

games)

24

(11)

(13)

8

Unusable: One Page, Little

Information

Michigan State (2), Nebraska

(1), Rutgers (0) (3 disrupted

games)

Unusable: Good Faith

Response with Too Little

Specific Information

Baylor (Private) (1), Iowa

State (0), Maryland (4),

Texas A&M (3) (8 disrupted

games)

Usable: Substantial or

Complete Response

Arizona State [PAC-12] (3),

Cal-Berkeley [PAC-12] (4),

Clemson [ACC] (1),

Colorado [PAC 12] (2),

Florida State [ACC] (4),

Illinois [Big 10] (0), Indiana

[Big 10] (2), Iowa [Big 10]

3

4

19

Washington-Huskies-UW-Football-Pac-12-to-utilize-KINEXON-SafeZone-for-rapid-and-

reliable-contact-tracing-155702211/ [https://perma.cc/GRG4-Z25F] [hereinafter PAC-12 to

Utilize KINEXON] (explaining the PAC-12 Conference’s announcement that it would use

KINEXON SafeZone technology to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in its football and

men’s and women’s basketball programs).

2021] COVID-19 PROTOCOLS 1051

Response: Acknowledgment and

Indefinite Delay

Arizona (2), Georgia (3), Georgia

Tech (3), Louisville (3),

Minnesota (2), Ohio State (2),

UCLA (1) (16 disrupted games)

7

(1), Kansas [Big 12] (2),

Kentucky [SEC] (0),

Michigan [Big 10] (3),

Mississippi State ($159 Fee)

[SEC] (2), Missouri [SEC]

(5), North Carolina [ACC]

(0), Oregon [PAC 12] (1),

Texas [Big 12] (2), Utah

[PAC 12] (3), Washington

[PAC 12] (4), West Virginia

[Big 12] (2) (41 disrupted

games)

Finding 1: The response rate for the survey was about 30%, a typical figure for

organizational responses to survey research.

123

• The response rate, counting only usable replies to the survey request, was

29.2% (nineteen of sixty-five).

• Among the eleven private schools, 90.9% did not respond to this survey.

Baylor, the lone exception, provided a good faith response that was too

incomplete to score.

• The NFL and NFLPA, also private entities that are exempt from FOIA and

Open Records laws, published their complete labor agreement addendum

for COVID-19 protocols.

• Eight public schools (12.3%) stated that they were exempt from providing

information to an out-of-state resident.

• Nine schools (13.8%) asked for one or more extensions in October 2020,

and as of December 31, 2020, had not provided information.

• Three schools provided such limited information that their responses could

not be considered a good faith reply. Two schools sent a cursory list of

COVID-19 symptoms; the other school sent a blank form for a player to

complete with a space for the first and last name and a space for whether

the player tested positive. The schools who sent a blank form for a player

to complete were Michigan State, Nebraska, and Rutgers.

• The nineteen usable responses came from public schools (100%).

123

See Yehuda Baruch & Brooks C. Holtom, Survey Response Rate Levels and Trends

in Organizational Research, 61 HUM. RELS. 1139, 1139 (2008) (stating that analysis of 1,607

studies published from 2000–2005 in seventeen refereed academic journals, and including

more than 100,000 organizations as respondents, found that the average response rate for