EP 1105-3-1

19 January 2009

PLANNING

BASE CAMP DEVELOPMET I THE

THEATER OF OPERATIOS

EGIEER PAMPHLET

Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

AVAILABILITY

Electronic copies of this and other U.S. Army Corps of Engineers publications are

available on the Internet at <http://www.usace.army.mil/inet/usace-docsl>. This site is the

only repository for all official USACE engineer regulations, circulars, manuals, and other

documents originating from HQUSACE. Publications are provided in portable document

format (PDF).

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY EP 1105-3-1

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

CEMP-OP Washington, DC 20314-1000

Pamphlet

No. 1105-3-1 19 January 2009

Planning

BASE CAMP DEVELOPMENT IN THE

THEATER OF OPERATIONS

Protecting and enhancing the life, health, safety, and quality of life of the service member

is at the heart of the United States Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) military support

mission. As a part of that mission, the Corps of Engineers and all members of the

engineer family stand ready to provide vital planning, engineering expertise, and other

support to the operational Army, military Services, and other federal agencies. In so

doing, the Corps provides direct support and benefit to Soldiers and members of other

services, as well as allied and coalition nations and citizens of host nations (HNs)

wherever there is a dedicated U.S. interest or presence. Base camp development is an

example where USACE leadership and expertise have become a recognized and highly

valued resource. Our support to combatant commanders (CCDRs) in this area ensures

that base camps can act as power projection platforms throughout full spectrum

operations while allowing the promulgation of the operational mission intent in a most

effective, efficient, and sustainable manner that enables force protection and

augmentation of the CCDR's mission assets. As part of our effort in supporting this

mission, we have developed this engineering pamphlet (EP) to support base camp

development. While this pamphlet can be used by an experienced military planner as a

base camp development planning resource, its primary purpose is to provide a more

detailed discussion of the topics presented in the USACE Base Camp Development

Planning (BCDP) Course. It provides the user an overview of base camp development

planning; one of the five considerations and processes that contributes to the overall

lifecycle of base camp development (see field manual [FM] 3-34.400). It does not

specifically address design, construction, operations (sustainment), or closure/turnover

considerations beyond the planning process. While there are many specialties and

functions associated with successful base camp planning and development, this pamphlet

focuses primarily on the engineer-specific areas of base camp planning. Finally, this EP

is not specific to any single functional or geographic combatant command; it provides

general planning guidance that the user must analyze, refine, coordinate and, ultimately,

adapt to meet the CCDR's guidance and needs.

1. Purpose. This pamphlet fills a fundamental role in meeting this mission requirement

and establishes a process for—

• Selecting suitable base camp locations while coordinating with CCDRs, the

U.S. Department of State (DOS), the Federal Emergency Management

Agency (FEMA), other federal agencies as appropriate, and the HN.

• Planning and documenting the detailed actions needed for a properly located

and sized base camp that consider related land areas, facilities, utilities, and

other factors to provide service members with the safest, healthiest, and best

living and working conditions in the theater of operations (TO).

• Planning and executing the cleanup and closure of a base camp in a manner

that meets U.S. and HN standards or those approved by the theater command.

2. Applicability. This pamphlet applies to all Headquarters, USACE (HQUSACE)

elements and all USACE commands having responsibility for or a role in supporting the

planning, development, or establishment of a base camp as directed by the appropriate

authority within the U.S. government.

3. Distribution Statement. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

4. References. Required and related references are at Appendix A.

5. Explanation of Acronyms and Terms. Doctrinal acronyms and special terms used in

this pamphlet are explained in the glossary. Many terms used by service members to

describe a base camp, however, have not yet been incorporated in the lexicon of current

joint and Army doctrine. For this pamphlet, the term base camp may, in some cases, have

applicability to some of the following terms: advanced operations base, forward

operations base, forward operating base, main operations base, base of operations

(specifically a designated facility), base, facility (where it applies to contingency support

operations), base complex, base development, forward logistics base, logistics base,

staging base, lodgment area, special forces operations base, bare base, enemy prisoner

of war (EPW) facilities, fire base, contingency operation base, contingency operation

site, contingency operation location, main operating base, forward operating site,

cooperative security locations, and convoy support centers.

I heartily endorse this document. Use it to enhance your knowledge and improve our

collective capability to meet this vital mission requirement.

FOR THE COMMANDER:

9 Appendices STEPHEN L. HILL

(See Table of Contents) Colonel, Corps of Engineers

Chief of Staff

• Planning and documenting the detailed actions needed for a properly located

and

sized base camp that consider related land areas, facilities, utilities, and

other factors to provide service members with the safest, healthiest, and best

living and working conditions in the theater

of

operations (TO).

•

Planning and executing the cleanup and closure

of

a base camp in a manner

that meets

U.S. and

HN

standards

or

those approved

by

the theater command.

2.

Applicability. This pamphlet applies to all Headquarters,

USACE

(HQUSACE)

elements and all USACE commands having responsibility for

or

a role in supporting the

planning, development, or establishment

of

a base camp as directed

by

the appropriate

authority within the

U.S. government.

3. Distribution Statement. Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

4. References. Required and related references are at Appendix A.

5. Explanation

of

Acronyms and Terms. Doctrinal acronyms and special terms used in

this pamphlet are explained in the glossary. Many terms used

by

service members to

describe a base camp, however, have not yet been incorporated in the lexicon

of

current

joint

and

Army

doctrine. For this pamphlet, the term base camp may, in some cases, have

applicability to some

of

the following terms: advanced operations base, forward

operations base, forward operating base, main operations base, base

of

operations

(specifically a designated facility), base, facility (where it applies to contingency support

operations),

base complex, base development, forward logistics base, logistics base,

staging base, lodgment area, special forces operations base, bare

base,

enemy prisoner

of

war (EPW) facilities, fire base, contingency operation base, contingency operation

site, contingency operation location, main operating base, forward operating site,

cooperative security locations, and convoy support centers.

I heartily endorse this document. Use it to enhance your knowledge and improve our

collective capability to meet this vital mission requirement.

FOR

THE

COMMANDER:

9 Appendices

(See Table

of

Contents)

lt\\Jl

)~PHEN

L. HILL

Colonel, Corps

ofEngineers

Chief

of

Staff

i

DEPARTMENT OF THE ARMY EP 1105-3-1

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

CEMP-OP Washington, DC 20314-1000

Pamphlet

No. 1105-3-1 19 January 2009

Planning

BASE CAMP DEVELOPMENT IN THE

THEATER OF OPERATIONS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Paragraph Page

Chapter 1. Introduction to Base Camps

The Operational Environment ............................................. 1-1 1-1

The United States Army ...................................................... 1-2 1-2

General Overview of Bases ................................................ 1-3 1-2

History of Base Camps ....................................................... 1-4 1-4

Types, Functions, and Construction Standards of Base

Camps ............................................................................. 1-5 1-5

Operational Challenges Associated with Base Camps ........ 1-6 1-14

Chapter 2. The Base Camp Development Planning Process

Introduction.......................................................................... 2-1 2-1

Description of the Base Camp Development Planning

Process ............................................................................. 2-2 2-1

Overview of Base Camp Planning Considerations.............. 2-3 2-5

Chapter 3. The Military Decision-Making Process and Master Planning

Process Relationship to Base Camp Development Planning

Introduction.......................................................................... 3-1 3-1

The Base Camp Development Planning Process and the

Military Decision-Making and Master Planning

Processes......................................................................... 3-2 3-1

Chapter 4. Preliminary Planning

Introduction.......................................................................... 4-1 4-1

Analyzing the Mission Statement and the Operation

Order ................................................................................ 4-2 4-2

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

ii

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

Paragraph Page

Analyzing the Supported Unit's Mission and

Requirements .................................................................. 4-3 4-4

Base Camp Allowances and Standards................................ 4-4 4-9

Operationally Related Variables.......................................... 4-5 4-9

Chapter 5. Location Selection

Introduction.......................................................................... 5-1 5-1

Location Selection Considerations ...................................... 5-2 5-2

The Interrelationship Between the United States

and the Host Nation ........................................................ 5-3 5-3

General and Special Considerations .................................... 5-4 5-8

The Location Selection Team .............................................. 5-5 5-10

Acquiring and Managing Location Selection Information.. 5-6 5-18

The Location Selection Process (In Country)...................... 5-7 5-20

The Location Selection Record............................................ 5-8 5-22

Review and Approval of the Location Selection

Record............................................................................. 5-9 5-24

Chapter 6. Land Use Planning

Introduction.......................................................................... 6-1 6-1

The Land Use Planning Process .......................................... 6-2 6-2

Steps for Land Use Planning................................................ 6-3 6-2

Chapter 7. Facilities Requirements Determination

Introduction.......................................................................... 7-1 7-1

The Facilities Requirements Development Process............. 7-2 7-2

The Tabulation of Existing and Required Facilities ............ 7-3 7-7

Final Review and Approval ................................................. 7-4 7-9

Chapter 8. Selected Infrastructure Topics

Introduction.......................................................................... 8-1 8-1

Sanitation ............................................................................. 8-2 8-1

Water Supply ....................................................................... 8-3 8-3

Energy.................................................................................. 8-4 8-4

Solid Waste.......................................................................... 8-5 8-6

Protection Considerations.................................................... 8-6 8-9

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

Paragraph Page

Chapter 9. General Site Planning

Introduction.......................................................................... 9-1 9-1

The Base Camp Development Site Plan .............................. 9-2 9-2

How to Prepare the Base Camp Development Site Plan ..... 9-3 9-2

Utility and Other Supplemental Plans.................................. 9-4 9-6

The Action Plan ................................................................... 9-5 9-8

How to Prepare the Base Camp Development Site Plan

Action Plan...................................................................... 9-6 9-8

The Review and Approval Process...................................... 9-7 9-10

Chapter 10. Base Camp Cleanup and Closure

Introduction........................................................................... 10-1 10-1

Legal Requirements and Considerations .............................. 10-2 10-2

Operational Considerations Related to Base Camp

Cleanup and Closure ........................................................ 10-3 10-3

Executing Base Camp Closure.............................................. 10-4 10-6

The Base Camp Cleanup and Closure Archive..................... 10-5 10-8

Environmental Consideration ............................................... 10-6 10-10

Appendix A - References.......................................................................................... A-1

Appendix B - Decision Briefing Format to Support the Military

Decision-Making Process .............................................................B-1

Appendix C - Sample Documents to Support Preliminary Planning.........................C-1

Appendix D - Sample Documents to Support Location Selection ........................... D-1

Appendix E - Sample Documents to Support Land Use Planning ............................E-1

Appendix F - Sample Documents to Support Facility Requirements

Determination................................................................................F-1

Appendix G - Sample Documents to Support General Site Planning ..................... G-1

Appendix H - Sample Documents to Support Base Camp Cleanup and

Closure ......................................................................................... H-1

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS (Continued)

Page

Appendix I - Selected Environmental Considerations Associated With

Base Camp Planning, Operation, Cleanup, and Closure.................I-1

Glossary ........................................................................................................Glossary-1

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-1

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Base Camps

1-1. The Operational Environment. U.S. military forces conduct operations against, and

alongside, state and nonstate participants in all regions of the globe. These operations

cover the full spectrum of conflict, from stable peace, through unstable peace, to

insurgency and general war (see Figure 1-1 and FM 3-0). Within this spectrum,

operational themes may be used to describe the dominant major operation or phase of the

campaign within the land force commander's area of operation (AO). Limited

intervention, peace operations, irregular warfare, and major combat operations are those

themes that are related to insurgencies and general war.

Figure 1-1. The spectrum of conflict

a. The Army’s operational concept, as detailed in FM 3-0, is called full spectrum

operations. This refers to the Army’s ability to combine offensive, defensive, stability,

and civil support operations, simultaneously. The first three of these pertain primarily to

U.S. military operations in foreign countries. The last, civil support operations, pertains

only to support provided to civil authorities, such as disaster relief and border security,

conducted within the United States.

b. The Army has long defined offensive and defensive operations. While

conducting stability operations has been the predominant mission throughout its

existence, the Army has only recently established stability operations as a core Army

mission (see FM 3-0). Joint Publication (JP) 3-0 defines stability operations as an

overarching term encompassing various military missions, tasks, and activities conducted

outside the United States in coordination with other instruments of national power to

maintain or reestablish a safe and secure environment, provide essential governmental

services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief. The

recognition of stability and civil support operations as core components of the Army

mission has greatly impacted how the Army views itself, trains, and conducts operations.

c. In addition to the full recognition of stability and civil support missions, the

Army now places greater emphasis on joint operations involving all U.S. military Service

branches; multinational operations with allied and coalition forces; and interagency

coordination with various U.S. and HN governmental and nongovernmental (NGO)

agencies. Cooperation with these entities, along with the expanded role of civilian

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-2

contractors, has numerous implications for the planning and conduct of operations. The

Army seldom plans and conducts operations strictly with Army assets. It now plans for

and integrates all of the applicable components of national power into its missions.

1-2. The United States Army. The U.S. Army is the primary land component of the U.S.

Armed Forces. It is a force which continually evolves to meet strategic, operational,

tactical, and organizational challenges. The Army’s current period of evolution, generally

referred to as Transformation, has changed the Army from a forward deployed force

based largely in Europe and Asia, to a force based primarily within the United States.

Organizationally, the Army has transitioned from a division centric to a brigade centric

force. This force is more modular than the previous Army structure and enables the Army

to better deploy only the specific assets required to conduct and support a given mission.

Further developments of lighter and more sustainable equipment are also making the

Army faster and better organized and equipped to conduct operations with a smaller

logistics footprint. In addition to implications regarding equipment, training, and

personnel, Transformation has required the Army to adopt an operational mind-set that is

expeditionary and campaign focused.

a. Expeditionary capability is the ability to promptly deploy combined arms forces

worldwide into any operational environment (OE) and operate effectively upon arrival.

Expeditionary operations require the ability to deploy quickly with little notice, shape

conditions in the operational area, and operate immediately on arrival (see FM 3-0).

Expeditions are conducted on short notice and are of generally limited scope and

duration. The forces involved are closely tailored to meet the requirements of the

expedition in order to reduce the overall support requirements.

b. Campaign capability is the ability to sustain operations as long as necessary to

conclude operations successfully (see FM 3-0). Campaigns are sustained operations, quite

often evolving from expeditions, which may have changing missions and requirements.

They require significant commitments of assets and a robust infrastructure to support and

sustain them.

c. U.S. forces conducting expeditions and campaigns from forward deployed

locations will seldom have the luxury of conducting their missions from established

installations. They will most often operate from base camps (the generic term for a

variety of types of facilities) with a variety of construction standards and facilities. These

camps may be already established in nations adjacent to the operational area, or they may

be established once the operation has begun. Depending on the situation, base camps may

be planned from the start of the mission but typically evolve over time in response to

emerging mission requirements.

1-3. General Overview of Bases. A base is a locality from which operations are projected

or supported (JP 3-10). Army bases overseas typically fall into two general categories:

base camps and permanent bases or installations. A base can contain one or multiple units

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-3

from one or more Services. It has a defined perimeter and established access controls, and

it takes advantage of natural and man-made features.

a. Base camps. A base camp is an evolving military facility that supports the

military operations of a deployed unit and provides the necessary support and services for

sustained operations. Base camps are typically designed to be used for short- to mid-term

periods, generally from a few months to a few years. They have a limited number of fixed

facilities constructed and typically have a well-defined perimeter and controlled access.

These facilities include various types of housing; sanitation; command and control (C2);

morale, welfare, and recreation (MWR); and supporting logistics infrastructure. These

facilities may include new or prefabricated construction and make maximum use of any

existing structures (with and without repair or modification). They are usually established

to support a specific mission or operation for an extended period of time and are closed at

the conclusion of that operation. These missions may include offensive, defensive,

stability, or civil support. Base camps are subject to a broad range of construction,

facility, and environmental standards, depending on the camp’s anticipated life span,

population, function, governing documents (for example, Central Command Regulation

[CCR] 415-5 [the Sand Book] or the Base Camp Facilities Standards for Contingency

Operations [the Red Book]), location, and the tactical and political situation.

b. Installations. An installation is a permanent location, designed and built for use

over the long term (decades). Installation facilities are generally designed and built by

civilian contractors according to U.S. construction standards. They are considered to be,

and are managed as, real property and are subject to strict and well-established design,

construction, management, and environmental regulations. Facilities on installations in

foreign countries typically match those found on installations within the United States

and are subject to a separate set of published standards. Installations are generally

managed, or experience a high degree of oversight, by civilians within Department of

Defense (DOD) agencies.

c. Base camps established for several years may evolve into installations. Often,

however, there is no clear point when this occurs. At either end of the time line (short-

term or long-term) the differences will be fairly clear. In the midterm, however, the

quality of life, construction, and environmental standards between base camps and

installations may experience significant overlap.

d. Base camp planners assist in the location, design, construction, and cleanup and

closure of base camps that support military forces or government organizations across the

spectrum of conflict. The BCDP process involves the integration of base camp types,

functions, allowances, and construction standards with the commander’s (customer’s)

requirements, resources, and available terrain. As such, base camps are not easily defined

entities. They are developed to meet various (sometimes competing) requirements, come

in all shapes and sizes, and integrate many similar characteristics. Above all, a base camp

is a physical location that provides forces (military or otherwise) with a secure, functional

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-4

location from which to conduct and sustain operations while providing an adequate

quality of life for its occupants.

1-4. History of Base Camps. Military forces have used base camps in various forms

throughout history. They were used for essentially the same purposes that they are

today—as temporary and secure locations to conduct and support operations. As with

today, they sometimes evolved into permanent installations that affected the local

political and economic situation on a long-term basis.

a. The Roman Legions established base camps that provided fortified locations

from which to support operations or to fall back on in emergencies. Scouts moved ahead

of the line of march to locate defensible locations with access to adequate food and water

supplies and transportation networks. These camps enabled the Roman forces to establish

secure bases to operate from, influence and control the local populations, conduct nation

building, and secure their lines of communication (LOC). In some cases the locations of

these camps were ultimately transformed into cities. The remains of other camps can still

be found today.

b. Throughout its history, the U.S. military has employed base camps in support of

operations. The Civil War saw a rise in the specialization of camps developed to meet

specific missions. Some camps were established for support operations, while others

were established specifically for combat operations. States established camps of

instruction where new recruits were equipped and received their initial training before

joining the forces that were engaged in active operations. Other camps were established

primarily as logistics bases to store supplies and forward them on to the armies in the

field. These armies would often establish temporary camps in support of their current

operations or winter camps where they would rest and train until the opening of the

campaign season in the spring. Other small camps and earthwork forts were established

to secure key terrain and LOC against enemy raids and insurgent groups. The standards at

all of these camps varied, depending on the length of the mission, the type of forces

deployed, the level of threat, and other aspects of the tactical situation.

c. On the frontier, the U.S. Army was faced with policing, protecting, and exploring

a large geographic area with limited personnel and resources. Permanent installations,

generally referred to as forts, were located at key locations such as harbors, river

crossing, and road networks. These installations often included buildings constructed of

brick and stone, well-developed fortifications, and housing for Soldiers and their families.

From these installations, a network of smaller camps and depots was established where

small detachments of personnel could secure LOC, conduct patrols, and provide a

“presence” to reassure the local populations. A variety of local materials was used in their

construction, and quality of life for the Soldiers using them was diverse.

d. During the Vietnam War, base camps became the focal point of operations and

not just a means of supporting the troops in the field. While continuing to perform their

historic support function, base camps were essential for providing security for local

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-5

populations. They were used as air bases for helicopter operations, patrol bases for forces

operating against the enemy, and fire support bases for artillery support. These camps

varied in size from the main division bases and airfields, often constructed with HN and

contractor assistance, to the smaller fire support and patrol bases that were constructed by

military personnel.

e. U.S. forces are presently deployed in base camps throughout the world. As with

camps throughout history, they vary in size and in quality of life based on the situation.

The OE has, however, made some changes in the appearance and operation of these base

camps. Compared to the camps of the past, they frequently have an improved quality of

life and are often subject to more stringent construction and environmental standards.

They also have a greater DOD civilian and civilian contractor presence.

1-5. Types, Functions, and Construction Standards of Base Camps. Base camps are

established to support a variety of missions across the full spectrums of conflict and

operations. Base camps are broadly defined by type and function, with facilities and

standards (construction, quality of life, and environmental) based on the camp’s

anticipated life span and population. The type of base camp provides a general idea of its

purpose and location in relation to the operation that it supports. The base camp's

function more narrowly defines its purpose and provides a better idea of the types of

facilities required in order to be effective. The anticipated life span further delineates the

base camp and helps to define the required standards and allowances.

a. Regardless of the type or function of base camp, the basic BCDP process and

sound engineering and master planning principles remain the same. As with any engineer

product, the end product is a reflection of the customer’s requirements, the “on the

ground” reality, and resource constraints. Ultimately, it is the responsibility of the CCDR

to determine the exact construction type based on locations, materials available, and other

factors to include specified standards (see FM 3-34, FM 3-34.400, and JP 3-34). The final

product, in terms of facilities and standards, is driven by the following five areas:

• Type and function of the camp.

• Anticipated base camp population (initially and follow-on occupation if

known).

• Anticipated camp life span.

• Standards used (Red Book, Sand Book, and others).

• Other command guidance (operation orders [OPORDs], operation plans

[OPLANs], and other directives). Security considerations will always be

integrated into planning guidance.

b. Types of base camps. Base camps consist of intermediate staging bases (ISBs)

and forward operating bases (FOBs) (FM 3-0). These are the two most common types of

base camps in support of military operations, but they are not the only possible variants

of base camps.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-6

(1) An intermediate staging base is a tailorable, temporary location for staging

forces and sustainment and extraction into or out of an operational area (JP 3-34). An ISB

is located close to the AO but out of the range of most enemy fires and political

influence. It allows forces to deploy, prepare, and train for operations. It is typically

located near developed airports, seaports, and/or other transportation facilities to allow

forces to deploy and redeploy with their equipment. It requires sufficient space for force

beddown to include surge capacity to handle rotating forces, equipment staging, and

necessary training areas. As with other bases, standards and allowances are determined

by the anticipated camp life span and population. These may include standards for

personnel assigned as long-term camp residents and separate standards for personnel who

are rotating through the base.

(2) Another type of base camp, a forward operating base, is an area used to support

tactical operations without establishing full support facilities (FM 3-0). While FOBs

range from small outposts to complex, large structures encompassing joint, interagency,

and multinational forces, they are primarily end users in the supply chain, oriented upon

the mission rather than sustainment. They are established to extend C2 or

communications, or provide local support for training and tactical operations.

Commanders may establish a FOB for temporary or longer operations. The FOB may

include an airfield or unimproved airstrip, an anchorage, or a pier along with other

logistics support infrastructure.

c. Functions of base camps. Base camps may be developed for a specific function or

may serve several functions. These functions determine what types of facilities are

required to support operations. While an ISB, by definition, has a specific function to

perform, FOBs may be developed for different purposes. A FOB may operate as a

multifunctional main operations base, a primarily tactical base, a logistics base, or in

support of training or civil-military operations. FOBs may also be established to support

humanitarian assistance and civil support missions. These base camp functions are not

specifically defined by doctrine, but do serve as a general guide to determine base camp

location and facility requirements. This section provides an overview of some of the key

characteristics of base camps that perform specific functions.

(1) Intermediate staging base. An ISB functions as a location where military forces

can stage into and out of the operational area. While generally similar to an FOB, it

includes the specific requirement to be able to handle the deployment and redeployment

of significant numbers of personnel and equipment, often over repeated rotations during a

period of several years. An ISB may serve as a “warm” base, where the infrastructure has

been developed to support possible contingency operations in a specific theater of

operations. A “warm” base generally has the capacity to support a large influx of

personnel and equipment and may have equipment and vehicles stored on location to

support operations and training. There will often be a small military and civilian force on-

site to maintain the base and the equipment until needed.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-7

(a) Size: Varies with the anticipated requirement, but may include the capacity for

up to several thousand personnel on-site at any given time.

(b) Location:

• Near the anticipated area of operations, but outside of the range of most

enemy fires and political influence.

• Close to airports and seaports (depending on the anticipated means of

deploying forces into theater).

• Close to road and rail networks to allow the rapid flow of personnel and

equipment.

(c) Base facilities:

• Housing. Adequate for the anticipated number of personnel (to include surge

requirements), generally consisting of buildings or modular/container units for

personnel assigned to the camp and tents for rotating personnel.

• Sanitation. Porta-johns up to a central sewer, depending on the camp location

and life span.

• Power. Usually provided by large on-site commercial generators or one or

more of the other Services' prime power units such as the Army 249th Prime

Power Battalion. In some cases, bases may use a central power plant or the

existing civilian electric grid.

• Fuel. Possibly extensive fuel support systems to include military- and civilian-

operated fuel bladders and below and aboveground fuel storage tanks.

• Water. Bulk water distribution, possibly including reverse osmosis water

purification units (ROWPU) or drilled wells.

• Aviation. Generally helicopter landing pads up to operational airfields,

depending on ISB location.

• Logistics. May include extensive warehousing and long-term, climate-

controlled vehicle storage and maintenance sites. Will generally have the

capacity to assist with sustaining military operations in the AO.

(d) Service member services:

• Medical. May include up to combat support hospitals with dental care. May

include a smaller medical clinic for personnel assigned to a “warm” base with

the ability to support rotational personnel.

• MWR. Depending on the length of time personnel may occupy the base, may

include up to theater facilities, post exchange (PX), internet cafés, long

distance phone service, ball fields, gyms, and organized recreation events.

• Other services. Finance, legal, and postal services and education or learning

centers may be available, based on the size and life span of the camp. Bath

and laundry services may include both military and civilian (tents, trailers, or

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-8

new construction). Dining facilities (DFACs) will generally be operated by

contractors; however, military food service personnel may be required

initially.

(2) Forward operating base (main operations base). A FOB functioning as a main

operations base will have a robust infrastructure to support a wide variety of missions. It

provides a base from which tactical forces can conduct and sustain operations. It will

generally include extensive service member support facilities and services and will often

include aviation facilities. In some circumstances, military training, civil affairs missions,

and even the capacity to support civilian political functions and NGO activities may be

included. Close coordination with the customer is essential to determine necessary

requirements and standards.

(a) Size: Varies with the anticipated requirement, but may include the capacity for

up to several thousand personnel on-site at any given time.

(b) Location:

• Adequate available land area, often with existing structures that can be

integrated into the camp.

• Close to, or including, aviation facilities.

• Close to, or including, seaport facilities.

• Close to road and rail networks to allow the rapid flow of personnel and

equipment.

• May be based on the tactical situation; however, the ability to support and

sustain operations will probably be more important than tactical requirements.

(c) Base facilities:

• Housing. Adequate for the anticipated number of personnel (to include surge

requirements), up to and including new construction of buildings (based on

camp life span).

• Sanitation. Porta-johns up to central sewer (and possibly portable sewer

treatment plants), depending on the camp location and life span.

• Power. Usually provided by large on-site generators (commercial, Army

prime power, or other Service power units), but some bases in developed

countries may use a central power plant or the existing civilian electric grid.

• Fuel. Possibly extensive fuel support systems to include military- and civilian-

operated fuel bladders and below and aboveground fuel storage tanks

• Water. Bulk water distribution, possibly including ROWPUs or drilled wells.

• Aviation. Generally helicopter landing pads up to operational airfields,

depending on location.

• Logistics. Includes extensive warehousing and material handling capability.

Must have the capacity to sustain military operations in the AO.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-9

(d) Service member services:

• Medical. May include up to combat support hospitals with dental care.

• MWR. Depending on the length of time personnel may occupy the base, may

include up to theater facilities, PX, internet cafés, long distance phone service,

ball fields, gyms, and organized recreation events.

• Other services. Finance, legal, and postal services may be available, based on

the size and life span of the camp. Bath and laundry services will generally

include military and/or civilian assets (tents, trailers, and possibly new

construction). DFACs will generally be operated by contractors; however,

military food service personnel may be required initially.

(3) Forward operating base (tactical base). A FOB may operate primarily as a base

from which tactical operations are conducted. It provides a secure location and will

generally have only enough logistics capacity to support the force occupying the camp.

There is a great degree of variability based on the size, duration, and tactical situation.

(a) Size: Highly variable based on the size of the force, but will generally be from

company (100) to brigade strength (3,000 to 5,000 with reinforcement and additional

sustainment assets).

(b) Location:

Based primarily on the tactical situation (with respect to the mission

requirements as well as the ability to defend the base).

Ability to sustain operations is a secondary (but still important) consideration.

(c) Base facilities:

Housing. Adequate for the anticipated number of personnel (to include limited

surge requirements), generally consisting of tents and the use of existing

structures but may include prefabricated housing (trailers) and limited new

construction.

Sanitation. Generally burn out latrines and porta-johns, but possibly sewer

lagoons or portable sewer treatment plants.

Power. Tactical generators up to large on-site generators (commercial or

Army prime power).

Fuel. Organic unit fuel trucks and possibly military (and perhaps civilian

contractor) bulk fuel bladders.

Water. Unit water trailers and bottled water. ROWPUs or drilled wells may be

located on some sites.

Aviation. Generally helicopter landing pads up to operational airfields,

depending on location.

Logistics. Generally limited to sustaining military operations in the unit’s AO,

but may include some more extensive facilities.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-10

(d) Service member services:

Medical. Usually limited to organic unit assets, but may include up to combat

support hospitals on larger bases.

MWR. Somewhat limited, but may include up to internet cafés, phone service,

and PX trailers (depending on camp size and location).

Other services. Finance, postal, and legal services are usually limited to

organic unit provided assets. Bath and shower facilities may be very limited.

DFACs may be operated by contractors on larger bases; however, military

food service personnel and meals, ready to eat may be used exclusively.

(4) Forward operating base (logistics base). A FOB may be developed primarily to

support logistics operations. These bases may be established at airfields, ports, adjacent

to highway networks, or along supply routes where they function as convoy support

centers, providing sustainment support to military and civilian convoys supporting

military forces. While still requiring tactical forces survivability measures for camp

security, the base’s primary purpose is to provide logistics support. As with any other

base, the size and life span, as well as function, will determine facility requirements and

standards.

(a) Size: Highly variable based on the size of the force, but will generally be from a

few hundred to a few thousand.

(b) Location:

Near road, rail, airport, and/or seaport facilities. Typically on a main supply

route (MSR).

Tactical considerations are a secondary (but still important) consideration.

(c) Base facilities:

Housing. Adequate for the anticipated number of personnel (to include surge

requirements), generally consisting of tents and the use of existing structures

but may include prefabricated housing (trailers) and limited new construction.

Sanitation. Generally porta-johns, but possibly sewer lagoons or portable

sewer treatment plants.

Power. Tactical generators up to large on-site generators (commercial or

Army prime power).

Fuel. Unit fuel trucks and military (and perhaps civilian contractor) bulk fuel

bladders.

Water. Bulk water distribution, possibly including ROWPUs or drilled wells.

Aviation. Generally helicopter landing pads up to operational airfields,

depending on location and mission profile of the using unit.

Logistics. Extensive warehousing and material handling capability.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-11

(d) Service member services:

Medical. Organic unit assets up to combat support hospitals.

MWR. May include up to internet cafés, phone service, PX trailers (depending

on camp size and location), gyms, and ball fields.

Other services. Finance, legal, and postal services may be available, based on

the size and life span of the camp. Bath and laundry services will generally

include military and/or civilian assets (tents, trailers, and possibly new

construction). DFACs will generally be operated by contractors; however,

military food service personnel may be required initially.

(5) Forward operating base (training base). In certain circumstances, a FOB may

be established to support the training of U.S., allied, coalition, and HN personnel. These

bases will have the same requirements as other FOBs of comparable size and life span. In

addition, training areas, classrooms, weapons ranges, and separate housing units (with

potentially different standards) for students and instructors will be required.

(6) Forward operating base (civil affairs operations). Occasionally, the situation

may require that separate camps be established to support civil-military missions. These

missions may include humanitarian assistance, nation building, and civil support (within

the United States). Bases developed for civil affairs missions or support may have

specific needs such as allowing relatively easy access to the base by HN civilians and

housing and support facilities for government and HN civilians and NGO personnel. A

high degree of compartmentalization within the camp may also be required, with separate

facilities for military and civilian personnel. Civil support missions conducted within the

United States, such as FEMA villages, may also require a more stringent application of

construction and environmental standards than those required in foreign countries.

(7) Internment/resettlement (I/R) facilities. There are often requirements to

construct camps for use as I/R facilities. Internment camps are designed to hold hostile,

or potentially hostile, enemy combatants or civilians. Resettlement camps are created to

hold civilians that have been displaced, either by war or natural disasters. FMs 3-19.40

and 3-34.400 provide additional guidance and sample plans.

(a) Internment camps. Certain camps are designed to hold enemy combatants.

These individuals may be held for varying lengths of time, from a few hours for

interrogation up to months or even years. As with any base camp, the facility standards

will vary according to the camp’s size and life span. As an internment camp, there are

certain unique requirements that must be considered. These requirements may include—

Highly compartmented housing areas to allow for detainee segregation.

Separate areas for personnel administration, interrogation, in-processing, and

possibly trial services.

Separate areas for military personnel and contractor housing.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-12

Additional force protection measures to ensure that detainees and military

personnel are kept separate and secure.

Additional food service, religious, and other cultural facilities to support the

detainees.

(b) Resettlement camps. In situations where war or natural disasters have impacted

the civilian population, resettlement camps are often required. These camps have the

potential to be quite large and may hold personnel for extended periods of time. While

the threat level and the corresponding need for security measures may be low,

resettlement camps still present a number of challenges and various considerations for

planners. Some of these include—

Housing areas that accommodate separate families and families with children.

Facilities for the elderly.

Substantial medical facilities.

Separate areas for civilians and military personnel.

Relatively easy access for the civilian population, while still implementing

adequate security measures.

Space for NGOs to operate.

Provisions for separating groups that are potentially hostile to each other.

Areas dedicated for aid distribution.

d. Base camp standards. Construction and facility allowances and standards are

based on the camp’s anticipated life span, population, theater standards and, ultimately,

customer requirements. JP 3-34 establishes the basic guidelines for allowable facilities

and construction standards based on anticipated camp life span. Other sources, such as

the Base Camp Facilities Standards for Contingency Operations, the Red Book for the

United States European Command and CCR 415-1, the Sand Book for the United States

Central Command (USCENTCOM), provide additional guidance which takes into

account theater requirements. JP 3-34 establishes two phases for base camp construction

and use—contingency for camps in operation less than two years and enduring for camps

in use for more than two years. Within these phases there are five sets of construction

standards that guide planners in the selection of allowable facility standards. These five

standards include—organic, initial, temporary semipermanent, and permanent. The

temporary standard bridges the gap between the contingency and enduring phases. In

some circumstances, standards may evolve as the anticipated life span of the camp

changes. This often happens when the mission duration is unclear. A camp which begins

using organic construction standards may evolve into one with temporary or higher

standards. When the mission duration is clear, planners may opt to design the camp based

on the standard that matches the anticipated life span. If the camp is going to be in

operation for more than two years, construction may begin using temporary or

semipermanent design standards.

(1) Contingency phase. Base camps developed in the contingency phase are based

on three standards—organic, initial, and temporary, with the temporary standard bridging

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-13

the gap to the enduring phase. Contingency phase construction is characterized by

generally austere living conditions and the use of organic unit equipment and military

engineer (rather than civilian contractor) construction (see JP 3-34).

(a) Organic. Organic construction is typical of what would be found in a tactical

assembly area. Organic standard construction is set up on an expedient basis with no

external engineer support, using unit organic equipment and systems or HN resources.

Intended for use up to 90 days, it may be used for up to six months.

(b) Initial. Characterized by minimum facilities that require minimal engineer effort

and simplified material transport and availability, initial standard construction is intended

for immediate use by units upon arrival in theater for up to six months. The primary

difference between organic and initial standards is the application of engineer effort to

improve living conditions above what the unit is able to accomplish on its own.

(c) Temporary. Characterized by somewhat minimal facilities, temporary standard

construction is intended to increase efficiency of operations for use extending to 24

months, but may fulfill enduring phase standards and extend to 5 years. It provides for

sustained operations and may replace initial standard in some cases where mission

requirements dictate and require replacement during the course of extended operations. It

requires extensive engineer support and may involve new construction, rather than

limiting operations to tents and existing facilities.

(2) Enduring phase. Enduring phase standards provide for a much improved quality

of life and facility efficiency over the contingency phase standards. Typically, the

enduring phase includes new construction by both military and civilian contractors, as

well as improved service member services and higher construction and environmental

standards. DOD construction agents (USACE, the Naval Facilities Engineering

Command [NAVFAC], or other such DOD approved activity) are the principal

organizations to design, award, and manage construction contracts in support of enduring

facilities. (See JP 3-34 for additional information.)

(a) Semipermanent. Semipermanent camps are designed and constructed with

finishes, materials, and systems selected for moderate energy efficiency, maintenance,

and life-cycle cost. Semipermanent standard construction has a life expectancy of more

than two, but less than ten, years. The types of structures used will depend on duration.

This standard may be used initially, if directed by the CCDR, after carefully considering

the political situation, cost, quality of life, and other criteria.

(b) Permanent. Permanent structures are designed and constructed with finishes,

materials, and systems selected for high energy efficiency and low maintenance and life-

cycle costs. Permanent standard construction has a life expectancy of more than ten

years. Construction standards should also consider the final disposition and use of

facilities and any long-term goals for these facilities to support HN reconstruction.

Congress and the CCDR must specifically approve permanent construction.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-14

e. Other construction standard considerations. The selection of specific construction

standards is based on more than just the anticipated life span of the camp. When selecting

standards, planners take into account the commander’s guidance, available materials and

labor resources, cost, and the tactical situation. If available, for instance, it may be more

efficient to use expeditionary base camp sets, such as the Army’s Force Provider, rather

than organic unit tents. If wood construction Southeast Asia huts (SEAHUTS) are

approved for temporary construction, it may be more efficient and effective (based on

resources, local climate and insects, and the local labor market) to use concrete masonry

unit construction instead. Planners must balance established standards with good engineer

judgment to obtain the best results.

1-6. Operational Challenges Associated with Base Camps. The planning and construction

of base camps present a number of challenges. As with any engineering or construction

project, there are time and resource constraints, laws and regulations, customer

coordination issues, and unclear/evolving missions. Some of the primary challenges

associated with base camps are theater entry conditions, mission duration, access to

resources, and competing requirements and visions.

a. Theater entry conditions. U.S. forces may enter a TO under permissive,

semipermissive or forced-entry conditions. These conditions refer to the relative level of

support that the governments or populations of the region will provide to U.S. forces. The

level of support or hostility that U.S. forces will encounter will have a significant effect

on base camp planning and construction.

(1) Permissive entry. In a permissive entry environment, U.S. forces are operating

with the support of the HN government(s) and can expect support from the majority of

the population. This situation makes base camp development much easier by allowing for

reduced tactical considerations, easier and more reliable access to resources, and

assistance from the local population in obtaining construction materials and contract

labor, including skilled labor assets. It also makes planning for base camps easier and

allows for the early reconnaissance of potential base camp locations.

(2) Semipermissive entry. A semipermissive environment presents greater

challenges. In this environment, U.S. forces may be invited into the nation or region by

the HN government(s); however, not all factions within the government or within the

local population will be supportive. This may dictate lower than desired facility standards

to avoid aggravating hostile factions. These situations may impede access to resources

and contract labor, will require greater security measures, and will limit the ability of

U.S. forces to conduct early reconnaissance of potential base camp locations. These

locations may also be driven, at least initially, by tactical rather than sustainment

concerns. Humanitarian assistance and civil support missions in response to natural

disasters also closely approximate a semipermissive environment. In these situations, the

damage caused by the disaster will have many of the same effects: limiting access to

resources, complicating transportation, and limiting initial reconnaissance.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-15

(3) Forced entry. Forced entry requires U.S. forces to conduct offensive operations

to gain a foothold or lodgment in a foreign country. These situations are very difficult to

plan for as access to potential base camp locations will be limited. A hostile government

or population will limit access to resources, both quantity and types available, and initial

base camp locations will be based on the tactical situation.

b. Mission duration. The length of the mission greatly impacts facility and standards

requirements. Short duration missions generally require fewer resources and have lower

standards, while longer missions require greater commitments. The most difficult

missions to plan for are those with an uncertain duration. Planners are forced to anticipate

requirements, and often completed work must be redone as the situation changes.

c. Access to resources. Access to resources, whether the ability to move them into

the theater or the availability within theater, impacts the planning and design of base

camps. In countries or regions with a well-developed infrastructure, materials and skilled

labor may be readily available, either by the relatively easy means of transporting them

into the area or through using local resources. If the infrastructure is poor or if the tactical

and political situations are not favorable (as in semipermissive and forced-entry

situations), resources will be harder to obtain.

d. Types of resources available. The relative abundance of certain types of

construction materials and the local labor market may also drive some base camp

planning and design decisions. The ability to obtain certain construction materials, such

as concrete rather then wood products, and the ability of the local labor force to work

with those materials, may dictate how camps are constructed. Other civilian trades, such

as the availability of skilled electricians and plumbers, will also impact designs and

construction management decisions.

e. Competing requirements and visions. While the customer is usually the final

decision authority, base camp planners must reconcile allowances (based on theater

guidance and established practices) with customer requirements and desires. The

customer may be the initial occupying unit or it may be the CCDR, the component

commander, or another element that is directing the construction of the base camp. In

fact, one of the initial challenges associated with base camp planning is obtaining an

estimate of the force structure that will be using the base camp. The force structure will

often change during planning and construction and will almost certainly change over the

base camp life span. Base camp planning balances the needs of the customer with the

reality on the ground, resource availability, and established standards. Often the

customer’s immediate needs, such as survivability requirements, compete with other

long-term needs. In long-duration missions, the changing environment and changes in

customers will require that planners adapt base camps designs to meet these changing

requirements.

f. Mitigation of uncertainty. Planners and engineers desire elegant solutions,

especially "right-sized" facilities and infrastructure. As soon as buried infrastructure is

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

1-16

deemed feasible for the camp, the uncertainties inherent in all these challenges are best

met by installing deliberately oversized utility runs for the greatest flexibility in evolving

camp operations and use. "Right-sized" utility infrastructure can quickly become a false

economy as it may require the user to not only pay to dig up the same dirt twice, but also

can disrupt camp operations while doing so. Aside from getting the right amount of land

in the right location, utility infrastructure can be the tightest physical chokepoint through

which camp operational surges must pass. By maximizing utility capacity/diameter, only

the loads on, and the length of, the system(s) change over the camp lifecycle.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

2-1

CHAPTER 2

The Base Camp Development Planning Process

2-1. Introduction. The BCDP process describes the method by which base camps are

located, designed, constructed, and eventually closed. The process, though generally

linear, is not an absolute. There are many variables, such as tactical and political

restrictions, as well as engineering, resource, and funding constraints that impact the

process. Some of the steps listed in the process may, or must, also occur concurrent with

other steps. The BCDP process is evolutionary and is not a lock-step process. It requires

constant revision and coordination. Base camp development planning is a time-sensitive,

mission-driven, cyclical planning process that determines and documents the physical

layout of properly located, sized, and interrelated land areas, facilities, utilities, and other

factors to achieve maximum mission effectiveness, maintainability, and expansion

capability in theater. This chapter describes the general steps that base camp planners

follow in the BCDP. Further chapters will discuss some steps in greater detail.

2-2. Description of the Base Camp Development Planning Process. The BCDP process

consists of several, not always linear, steps. This process relates to the master planning

and military decision-making processes that are further discussed in Chapter 3. The final

product is a completed base camp plan that provides a logical and documented solution

for a base camp location, land usage, and facilities that will support the needs of the

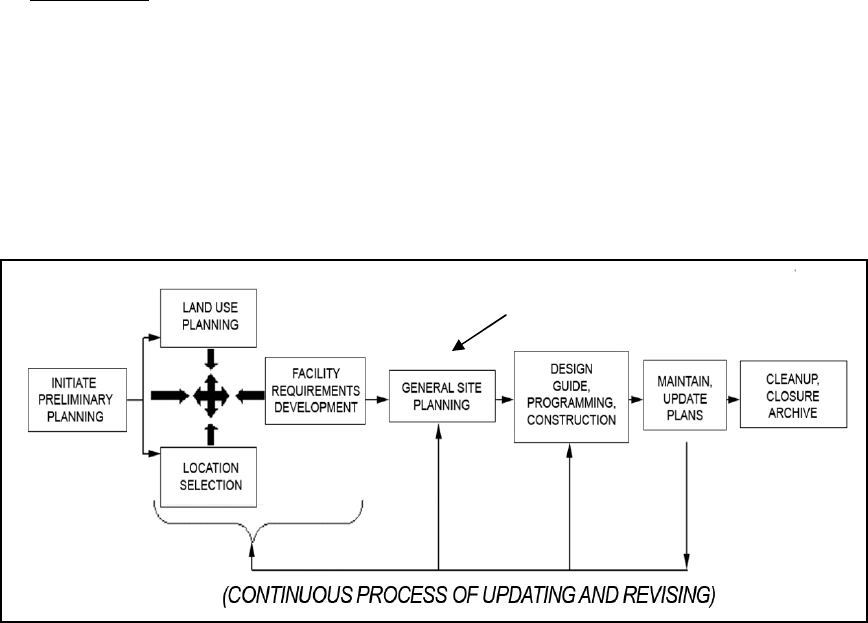

customer and mission accomplishment. As shown in Figure 2-1, page 2-2, the steps are—

Initiate preliminary planning.

Location selection.

Land use planning.

Facility requirements development.

General site planning.

Design guide, programming, and construction.

Maintain and update plans.

Cleanup, closure, and archive.

a. Depending on the circumstances, not every step may be necessary for planners to

evaluate or execute. Oftentimes, the customer or the HN will have selected or will dictate

the base camp location. In other cases, planners may be asked to provide support to the

process, and the process may already be under development. In this instance, a base camp

has typically been located, a land use plan developed, and the facilities requirements

determined by military forces on the ground. The planner may be asked to support only

the general site planning, provide designs for new construction, or provide guidance on

typical of the environment where base camp planners operate. Regardless of the step in

which planners enter into the process, a working knowledge of the BCDP process is

necessary to enable them to provide the best possible guidance and, ultimately, a product

that best supports the customers needs.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

2-2

Figure 2-1. The base camp development planning process

b. It probably will be necessary to consider some steps in the process concurrently

with others. In time constrained situations, or situations where base camp planners are

involved after construction has already started, design and construction of certain aspects

of the base camp may be required before completion of the full BCDP process. For

example, once identified, survivability measures may be designed and construction

initiated before completing the general site plan or even before completing the entire land

use plan. This is not the preferred method, but it is a reality that will happen due to

mission and funding requirements. Planners should advise commanders that executing

construction before completing a plan can lead to less than optimal base camp master

plans, increased costs, and potentially increase the time required to complete the base

camp. In any case, programming funds for construction needs to begin as soon as it is

feasible to ensure proper resourcing. Where possible, base camp cleanup and closure

should be integrated early into the planning process. Early integration of cleanup and

closure activities, such as planning ahead for how sanitation facilities will be closed out,

can avoid or reduce future challenges. The following steps make up the BCDP process:

(1) Initiate preliminary planning. Early and thorough planning is essential for any

endeavor. Base camps must integrate competing requirements effectively in order to

operate efficiently. Initiating preliminary planning is essentially completing a mission

analysis—gathering the available information and determining what additional

information is required. As noted above, base camp planners may enter the process at this

initial step or somewhere further along the process. Performing a mission analysis,

whether completed by the base camp planner or by forces already on the ground, is the

vital first step. Mission analysis is where the planners answer basic questions and develop

requests for information (RFIs) about the project. Mission analysis is also the

corresponding first step in the military decision-making process (MDMP). This step is

essential to understanding the environment, both physical and operational, in which the

camp will operate. Chapter 4 covers mission analysis in relation to base camp planning in

greater detail.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

2-3

(2) Location selection. Finding the best possible location for the base camp requires

balancing tactical and operational requirements and the ability to sustain the camp with

terrain factors such as urban or rural areas, drainage, soils, vegetation, and topography. In

some cases base camps may be located on existing facilities. In other cases they may be

located on undeveloped land. In either case, it requires a careful balancing of

requirements to obtain the best location that meets operational, sustainability, and

engineering requirements (see Chapter 5).

(3) Land use planning. Although land use planning begins in the early stages of the

BCDP, it requires the planner to conduct a facility requirements analysis before it can be

finalized. Additionally, since land use can be impacted by the site selected, the planner

should confirm that the location selected is adequate and has been approved for the base

camp. This step in the process integrates the military units’ requirements (such as

survivability measures, housing, motor pools, and storage areas) with land use affinities

and terrain restrictions. It provides a general overlay of land use areas within the

proposed base camp (see Chapter 6).

(4) Facility requirements development. Facility requirements reflect the integration

of facility allowances with unit requirements. Allowances are based on the type of unit,

its size, and the anticipated life span of the base camp. These allowances are found in the

theater-specific guidance documents such as the Sand Book and include areas such as

square feet of housing space, square feet of command space, and allowances for specific

facilities such as chapels and movie theaters. JP 3-34 provides guidance related to facility

standards. Once allowances have been determined, they are reconciled with specific unit

requirements by validating or adjusting those requirements based upon specific unit

needs. For example, the Sand Book may specify a certain amount of square feet for

vehicle parking. Coordination with the unit, however, may reveal that they have specific

requirements, such as turning pads for armored vehicles. In addition, the theater guidance

documents do not take into account every unit requirement. Coordination with the unit

may reveal, for instance, that they have water purification units with specific needs.

Planners must work with the customer to reconcile what is allowed versus what is

required (see Chapter 7). Adjustments to these allowances must be justified.

(5) General site planning. Once preliminary site planning has been completed,

general site planning further refines the product. General site planning takes the initial

land use plan, facility requirements, and coordination with customer requirements, and

completes the base camp design. It includes individual building layouts shown within the

preidentified land uses. In this step, final decisions with regard to facility types,

standards, construction, and the final location of specific structures and facilities are

made (see Chapter 9).

(6) Design guide, programming, and construction. The design, programming, and

construction of base camps begin as early as possible in the BCDP process. This early

start is essential to ensuring that funding and resources are available and that the camp is

completed in time to conduct its mission.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

2-4

(a) Design. In most instances, it is necessary to design facilities for base camp use.

Although the design effort for some structures, such as vehicle parking areas, will be

minimal, others may require significant design effort. Beginning the design process early

is essential in order to determine facility types and required resources and make

recommendations on labor sources. Planners must balance quality of life, resources, and

funding constraints to determine the most efficient and cost effective designs. Depending

on the allowable standards, some facilities, such as facilities for housing and recreation,

aviation, sanitation, electrical distribution, and survivability measures, may require

significant design efforts. When facility allowances provide for new construction to

accommodate troop housing, for example, there may be several design options available

(tents, prefabricated trailers, SEAHUTs, or concrete/masonry construction). Selecting

designs early is critical to ensure adequate and timely resource availability. Where

possible, use suitable existing structures, established designs (such as those found in the

Theater Construction Management System [TCMS]), and prefabricated buildings. When

new construction is required, use established techniques, methods, and materials to

simplify planning, material, and labor requirements. The selected design determines, and

is also influenced by, resource requirements and availability. As such, planners must

select designs which can be supported by available construction materials and other

resources. The availability of materials will depend on the local market, access to other

markets (which may be determined by the military and political situation), transportation

assets, and available funding; for example, it may not be practical to design toilet

facilities with flush toilets if the resources (to include water) are not available. The

selection of a particular design also impacts, and is driven by, labor availability. The

labor for base camp construction may be supplied by military forces, contractors, or HN

workers. Each labor source has certain strengths and weaknesses based on equipment,

training, and experience. If certain labor assets are available, such as HN workers, it may

be beneficial to select designs that meet the local labor skills. Conversely, certain designs

may not be supportable based on the available labor pool. Designing wood frame

structures for use in a desert environment may not be the best choice if the local labor

pool is not familiar with it. They may, however, be skilled in masonry construction.

Considering the anticipated labor availability is an important part of the design process.

(b) Programming. Programming for funds must be completed as soon as possible to

ensure adequate support. This is especially important if construction will involve the use

of contractors or HN personnel, lease payments are required, or restoration and/or

damage payments are anticipated. In some circumstances, certain funds may only be used

for specific purposes. Consult with contracting representatives to determine fund

availability, restrictions on use, and information on how to obtaining funds and arrange

for payment to vendors. The contracting representatives, including those associated with

civil affairs units, can also provide guidance on the available labor pool, HN contractors,

and bid submission procedures and guidelines. If the project is congressionally funded,

DD Forms 1391 are required and can be prepared by a service member with the proper

expertise and experience. Upon completion, DD Forms 1391 must be reviewed and

certified by the appropriate level commander or his properly designated representative.

EP 1105-3-1

19 Jan 09

2-5

(c) Construction. Construction of key facilities, in particular those required to

support survivability measures, should begin as soon as plans are approved. Construction

may be accomplished by military engineer units, contractors, or HN personnel (both HN

contractors and HN personnel under military unit supervision). Base camp planners must

determine, in conjunction with the construction unit, the proper sequence of events and

the critical path required to execute construction in a timely and efficient manner. HN

laborers and contractors may not adhere to expected construction and safety standards.

The implementation of an effective quality assurance and quality control plan is essential

to maintain standards, conserve resources, and maintain safety. In the often fluid nature

of deployments, logistic and labor shortages can also arise at short notice. Where

possible, anticipate and plan for delays and ensure adequate lead time to accommodate

logistics requirements.

(7) Maintain and update plans. All construction projects require the maintenance

and updating of construction plans. As these plans are altered, change drawings and

diagrams must be completed. The contract must specify receipt of as-built plans for each

portion of a project before payment for that portion or risk failure to capture the

information. These plans are especially important where safety or environmental matters

are involved. These include areas such as electrical systems (especially if buried lines are

involved), sanitation systems (such as buried sewer lines, sewer lagoons, and latrine pits),

ammunition holding areas, training areas (especially those that produce unexploded

ordnance (UXO), land fills/burn pits, and hazardous material (HM)/hazardous waste

(HW) storage and disposal sites. In addition, the land use plan, the tabulation of existing