Mitchell Barnes and Wendy Edelberg

ECONOMIC ANALYSIS | SEPTEMBER 2022

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the

Business Sector Since 2020

THE HAMILTON PROJECT MISSION STATEMENT

The Hamilton Project seeks to advance America’s promise

of opportunity, prosperity, and growth.

We believe that today’s increasingly competitive global economy

demands public policy ideas commensurate with the challenges

of the 21st Century. The Project’s economic strategy reects a

judgment that long-term prosperity is best achieved by fostering

economic growth and broad participation in that growth, by

enhancing individual economic security, and by embracing a role

for effective government in making needed public investments.

Our strategy calls for combining public investment, a secure social

safety net, and scal discipline. In that framework, the Project puts

forward innovative proposals from leading economic thinkers—

based on credible evidence and experience, not ideology or

doctrine—to introduce new and effective policy options into the

national debate.

The Project is named after Alexander Hamilton, the nation’s

rst Treasury Secretary, who laid the foundation for the modern

American economy. Hamilton stood for sound scal policy, believed

that broad-based opportunity for advancement would drive

American economic growth, and recognized that “prudent aids

and encouragements on the part of government” are necessary

to enhance and guide market forces. The guiding principles of the

Project remain consistent with these views.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors are grateful to John Haltiwanger and Martin Baily

for their insightful feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. This

document would not have been possible without the help and

encouragement of Natalie Tomeh, Moriah Macklin, Marie Wilken,

and Lauren Bauer. Lastly, the authors would like to thank Jeanine

Rees for all of her work with the graphic design and layout of this

document.

September 2022

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the

Business Sector Since 2020

Mitchell Barnes and Wendy Edelberg

The Hamilton Project

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 1

Introduction

e onset of the COVID-19 pandemic posed an unprec-

edented threat to the survival of America’s small businesses.

As public health orders at the end of April 2020 restricted

regular activity, more than 40 percent of small businesses

reported temporarily closing a location in the previous

week, with more than 70percent of businesses in the most-

aected service-sector industries reporting closures.

1

Many

feared that, if the pandemic prevented those businesses from

reopening, widespread small business failures could be con-

sequential to the economy and ultimately hamper the recov-

ery much as they did following the Great Recession.

Instead, the business sector appears to have weathered

the COVID pandemic and found a renewed gear of dyna-

mism in the process. According to newly released Business

Employment Dynamics (BED) data from the Bureau of La-

bor Statistics (BLS), nearly 450,000 more business establish-

ments were open for operation at the end of 2021 than at the

end of 2019—double the number of businesses created on

net from the end of 2017 through 2019. is result reects

positive signs in both business survival and new creation.

Although business closings spiked in the rst half of 2020,

data show that most of those closings were only temporary

and that many businesses had reopened within four quar-

ters. Meanwhile, the surge in new business applications that

began in mid-2020 appears to have translated into a near-

record level of new business creation. From the third quarter

of 2020 through the end of 2021, there were nearly 2million

new establishment births, which is more than 20 percent

above the pace of 2018–19.

is entrepreneurship in the face of the COVID pan-

demic also appears to be an international trend. e Econ-

omist found that, in the fourth quarter of 2021, enterprise

entries across Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD) countries were 15percent higher

than they had been before the pandemic (“All Over the Rich

World” 2022). Overall, the authors estimate that an extra

1million rms have been created since the rst lockdowns

compared to prior trend.

Patterns across US industries reveal evidence of econom-

ic restructuring induced by the pandemic period. Many of

the same industries in which existing businesses experienced

severe declines in revenue and elevated establishment exits

in 2020, including restaurants and other, generally personal

services such as hair salons, have also seen some of the larg-

est surges in new business creation (Bungton et al. 2021;

Crane et al. 2022). Other new business activity, including on-

line retail and data services, reect new opportunities in the

transition to a more remote environment (Haltiwanger 2022).

While questions remain around the contribution of these new

dynamics to job creation and productivity, the persistence of

these shis and the continued resilience of small businesses

will play key roles in determining the path of the recovery

moving forward.

1. Data from rst survey period of Census Bureau’s Small Business Pulse Survey,

collected between April 26–May 2, 2020.

Outcomes of Initial Business

Closings

Public health orders issued in March and April of 2020 im-

mediately pushed many businesses to shut down operations

as policymakers pursued a strategy to freeze the economy

in place until the pandemic subsided. A key data challenge

in real time was determining whether a closing had resulted

in a subsequent reopening or in a permanent establishment

death.

2

With the hindsight of new BED data, we can now see

that the 735,000 closings in the second quarter of 2020 did

in fact lead to a quarterly record of nearly 330,000 establish-

ment exits. As shown by the solid purple lines in Figure 1,

deaths of service-sector establishments (panel A) reached

an unprecedented peak of 290,000 in the second quarter of

2020, while deaths among goods businesses (panel B) spiked

to a high not seen since 2010.

However, despite establishment deaths exceeding pre-

pandemic trend by roughly 90,000 in the second quarter, BED

data suggest that the abrupt nature of the COVID lockdowns

and the reopening of the economy allowed a surprising num-

ber of closed establishments to reopen. e dotted purple

lines in the two panels of Figure 1, labeled “Temporary Shut-

downs,” show the number of closed establishments in each

quarter that were later determined to have reopened within

four quarters. In normal periods, temporary shutdowns re-

ect both seasonal businesses and short-term distress. Dur-

ing the second quarter of 2020, however, the number of busi-

nesses shutting down spiked to nearly double the quarterly

peak reached during the Great Recession. Relative to pre-pan-

demic trend, these temporary shutdowns jumped by almost

220,000 establishments. In other words, of the total 305,000

businesses that closed in the second quarter of 2020 above

trend levels, more than 70percent were able to reopen. at

rate was slightly higher among goods-producing businesses

and slightly lower among service-sector businesses. Moreover,

many establishments appear to have been able to reopen im-

mediately: the third quarter saw a surge in reopenings that

was just 36,000 fewer than the second quarter’s shutdowns.

e pace of exits slowed dramatically by mid-2020, with

the second half of the year experiencing 3percent fewer exits

than the second half of 2019. At that time the composition

of the most aected businesses also began to change. Initial

exits were concentrated among businesses that had suered

most from early COVID restrictions, which were predomi-

nately those in the service sector that relied on face-to-face

customers and that were unable to remold their operations

for a remote environment. In the rst half of 2020 busi-

nesses in leisure and hospitality, education, and health-care

services experienced nearly 70percent more exits than they

had in the rst half of 2019. But, in the second half of 2020,

2. BLS rst reports total establishment closings roughly two quarters aer the

end of each survey period, before retroactively recategorizing those closings

either as reopenings or establishment deaths, depending on whether a busi-

ness had reopened during the four subsequent quarters. For example, the

current BED data release provides data on total closings through the end of

2021, while the subset of establishment deaths is available only through the

rst quarter of 2021.

2 The Hamilton Project • Brookings

the only industries that experienced more exits than in 2019

were information and nancial services, where above-trend

business closings have continued through the end of 2021.

Overall, services accounted for almost 90 percent of total

establishment deaths from the start of 2020 through March

of 2021. is disproportionate impact on the service sector

during the COVID recession contrasts starkly with earlier

recessions.

Meanwhile, the record pace of new business creation

that began in mid-2020 achieved the feat of fully recovering

the number of establishments lost through exits by the end

of 2020. And, through March of 2021, 107,000 more estab-

lishments had been created than had been destroyed since

2019.

3

Shown in Figure 1 as solid green lines, establishment

3. Observed establishment births from BED data in 2020Q1 have been adjusted to

remove a spike in births that were specic to education and health services that

was not present in data vintages prior to the latest BED annual revision. Follow-

births have continued rising in both the goods and service

sectors, to combine for historically high levels of business

creation through the end of 2021. Many of these new births

are among the most pandemic-aected industries that expe-

rienced earlier business exits, including leisure and hospital-

ity, while other new births appear to be in industries that

might have been beneciaries of shis in COVID-era con-

sumption and mobility patterns, such as transportation and

warehousing (see Figure 7 below).

ese results diverge signicantly from the aermath of

the Great Recession, when the rate of new business start-ups

remained depressed for more than a decade: by 2018 the rate

of start-up formation remained 24percent lower than it had

ing Decker and Haltiwanger (2022) the number of establishment births have

been reduced by 36,000 in 2020Q1. However, employment data from births

have not been adjusted. BLS has advised that these data revisions and additional

information will be published with the upcoming 2022Q1 data release.

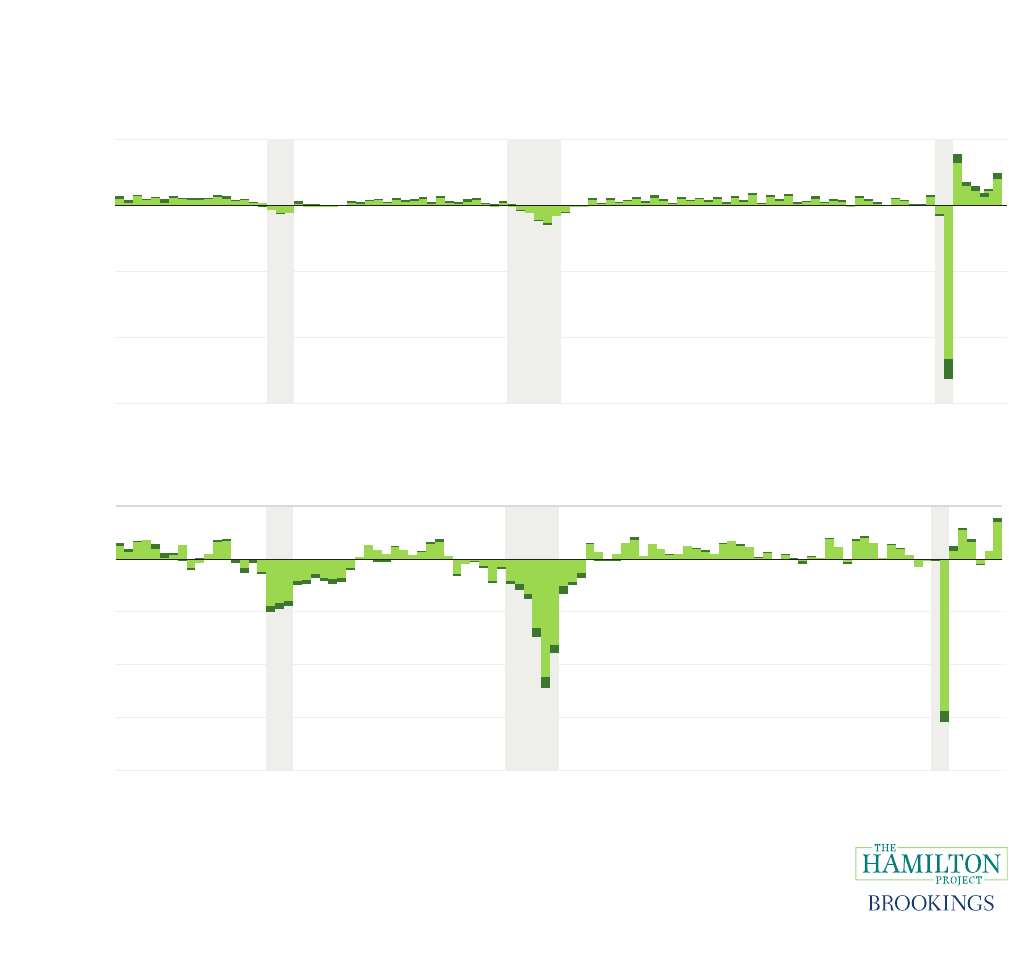

FIGURE 1

Establishment Deaths and Births Relative to Temporary Shutdowns and

Reopenings

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021

Number of establishments

(in thousands)

Number of establishments

(in thousands)

Establishment

births

Establishment

deaths

Temporary shutdowns

Reopenings

20

30

40

50

60

70

1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021

A. Service Sector

B. Goods Sector

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Figures present quarterly data for the number of establishment births and reopenings through the end of 2021.

Data on establishment deaths and temporary shutdowns are available only through 2021Q1 due to lagged reclassica-

tion of “total closings,” which are not shown. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray shading indicates recession peri-

ods. Y-axes for services and goods sectors are shown at different scales.

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 3

been in 2006. is lower rate of business formation partially

contributed to the slow economic recovery of the 2010s (Din-

lersoz et al. 2021). As of this writing, business destruction

and creation since 2020 more closely resemble the Dot Com

period. Both recoveries were relatively brief and returned to

positive net establishment growth within the rst year of the

start of the recession. And net business creation was largely

led by service industries early on in each of those recoveries.

Employment Impacts of

COVID Business Churn

While labor markets were initially jolted by the early wave

of business closures, the vast majority of employment losses

by the end of June 2020 stemmed from contractions among

businesses that remained open. First, the establishment

deaths that did occur over the COVID period led to smaller

employment impacts than establishment deaths in prior re-

cession episodes. Based on the ve quarters of available data

through March of 2021, a total of 1.3million establishment

exits resulted in the loss of 3.9 million jobs. Over similar

spans aer the onset of the prior two recessions, the Great

Recession had lost 1.2 million establishments and 4.4 mil-

lion jobs, whereas the 2001 recession lost 1.0 million es-

tablishments and an even greater 5.7million jobs. Second,

the severe contraction of payrolls dwarfs the employment

losses from closed businesses. In the second quarter of 2020,

17.5million (or 86percent of the gross 20.4million jobs lost)

resulted from contractions.

Figure 2 highlights these contributions over time,

showing employment ows driven by expansions net of

FIGURE 2

Employment Contribution of Openings and Expansions Net of Closings and

Contractions (Different Scales)

Net employment flows

(in millions)

Net employment flows

(in millions)

A. Service Sector

B. Goods Sector

-15

-10

-5

0

5

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

-2.0

-1.5

-1.0

-0.5

0.0

0.5

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

Expansions less Contractions

Openings less Closings

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Figures present net quarterly employment ows consolidated into two groups: “Expansions less Contractions” re-

fers to the net of employment gained at expanding establishments, minus employment lost from contracting establish-

ments. “Openings less Closings” refers to employment gained at reopening and newly created establishments, minus

employment lost from establishments closing either permanently or temporarily. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray

shading indicates recession periods. Y-axes for service and goods sectors are shown at different scales.

4 The Hamilton Project • Brookings

contractions and driven by openings net of closings (with-

out distinguishing between temporary and permanent clos-

ings). As shown by the light green bars, during the initial

second-quarter downturn, employment lost from contract-

ing establishments outweighed gains by expanding estab-

lishments by 11.6 million jobs among service-sector busi-

nesses and another 1.4million jobs among goods producers.

In that same quarter, jobs lost due to closing establishments

outnumbered those gained by reopenings and newly created

establishments by 1.6 million, with services accounting for

1.5 million of those.

Moreover, the large number of jobs initially lost

through contractions had not been fully recovered by the

end of 2021, with payroll expansions remaining 3.1million

jobs short among those same businesses. On the other hand,

the jobs lost through initial establishment closings had been

more than fully recovered by employment gains among re-

openings and newly created businesses. In total through

2021, BED data suggest that nearly 450,000 more establish-

ments had opened than closed since the beginning of 2020,

and that these new businesses had contributed a net 500,000

jobs to the recovery. Alone, births of new businesses created

an average of 1million new jobs in each of the nal three

quarters of 2021, driven mostly by small establishments

(shown in Figure 3).

Business and employment creation have been quite dif-

ferent from what they were in the prior two post-recession

periods. Over a similar two years from the start of the Great

Recession, 250,000 fewer establishments were in operation,

costing the economy nearly 540,000 jobs. Most striking is

the extended employment downturn among goods produc-

ers present in both earlier recessions that the COVID period

FIGURE 3

Employment Contribution of Openings and Expansions Net of Closings and

Contractions (Shared Scales)

Net employment flows

(in millions)

Net employment flows

(in millions)

A. Service Sector

B. Goods Sector

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

Expansions less Contractions

Openings less Closings

-11.6 million/

-1.5 million

-3

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Figures present net quarterly employment ows consolidated into two groups: “Expansions less Contractions” re-

fers to the net of employment gained at expanding establishments, minus employment lost from contracting establish-

ments. “Openings less Closings” refers to employment gained at reopening and newly created establishments, minus

employment lost from establishments closing either permanently or temporarily. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray

shading indicates recession periods. Employment ows for service sector in 2020Q2 are not shown to scale.

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 5

has largely avoided. For instance, by early 2010, which was

the last quarter of declining employment in the Great Reces-

sion, the goods sector constituted 97percent of the net em-

ployment lost by establishments that had closed since early

2008. Construction employment alone accounted for nearly

60 percent as a result of the housing market’s collapse. In

all, it took until mid-2011, or 14 quarters, for employment

gained from openings in the goods sector to exceed the em-

ployment continuing to be lost from closings. In contrast,

the brief two-quarter COVID downturn saw an immediate

rebound to positive employment growth from net openings

in the third quarter of 2020, largely as a result of reopenings

from earlier shutdowns. And by the fourth quarter of 2021,

reopening and newly created establishments in the goods

sector had more than fully recovered total employment lost

by closings, while the service sector had reached that thresh-

old in the quarter prior.

Employment Flows by Firm Size

Payroll contractions of larger rms largely drove the precip-

itous decline in employment in the second quarter of 2020.

Figure 4 shows employment ows from openings net of clos-

ings and expansions net of contractions for rms with 1–49

employees and rms with 50 or more employees. Nearly

70percent of total second-quarter employment losses came

from larger rms contracting (the dark green bar), where

rms with 250 or more employees accounted for half the to-

tal alone (not shown).

As is typically true (partly due to data construction),

employment eects from rm closings were concentrated

among small businesses, with businesses with 1–49 em-

ployees accounting for 93percent of all workers aected by

closings at the end of June of 2020.

4

ese employment ows

support earlier studies that showed initial closures con-

centrated among smaller businesses, meanwhile shutdown

rates at the largest businesses remained near pre-pandemic

norms (Crane et al. 2022).

Smaller rms have been a key driver of employment

growth throughout the recovery, recovering 96 percent of

their initial loss by the end of 2021, versus 71 percent for

4. Due to the dynamic method used in tabulating BED employment ows by

rm size, which allows movements across size classes, a portion of employ-

ment ows may reect downsizing and growing rms moving across the

50-employee threshold.

FIGURE 4

Employment Contribution by Firm Size

Net employment flows (in millions)

-16

-8

-12

-4

0

4

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

Expansions less Contractions (1-49 employees)

Expansions less Contractions (50+ employees)

Openings less Closings (1-49 employees)

Openings less Closings (50+ employees)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Net quarterly employment ows, split by size of rm, are consolidated into two groups: “Expansions less Contrac-

tions” refers to the net of employment gained at expanding rms, minus employment lost from contracting rms. “Open-

ings less Closings” refers to employment gained at reopening and newly created rms, minus employment lost from rms

closing either permanently or temporarily. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray shading indicates recession periods.

6 The Hamilton Project • Brookings

larger rms. Encouraging as a sign of business creation,

much of the employment recovery among rms with 1–49

employees has been driven by new establishments and re-

openings (more easily seen in Figure 5). ose gains exceed-

ed total losses from closed businesses by 210,000 since the

beginning of 2020 through the end of 2021. Small business

expansions have also contributed to the employment recov-

ery, as their net expansions of payrolls were responsible for

more than 30 percent of total employment gains in 2021.

Yet, by the end of 2021, expansions among small businesses

had yet to recover roughly 410,000 employees that were ini-

tially lost by contractions, while expansions at rms with

over 50employees had yet to recover more than 3million.

In comparison to past recessions, COVID stands out

due to the the quick recovery of jobs, in particular those con-

tributed by small rms. From the third quarter of 2020 to the

end of 2021, small rms with 1–49 employees accounted for

roughly 40percent of total employment growth, compared

to just 26 percent during the rst four positive quarters of

employment growth following the Great Recession. In this

respect, also, the COVID recovery more resembles the Dot

Com period, during which small rms contributed roughly

40percent of net employment growth. While the brevity of

the COVID downturn is unique in many ways, at the end of

2001 net openings among the smallest rms similarly recov-

ered in just two quarters to contribute positive employment

growth, despite continued employment losses in larger rms

and contracting small rms.

Employment and Job Openings

by Establishment Size

Additional data on employment and job openings by es-

tablishment size, rather than at the rm level, help provide

insight into which types of businesses were initially most

aected—and more recently, which types are seeking to ex-

pand through hiring. Figure 6a, displaying data from the Job

Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS), shows the

cumulative change in employment since February 2020 by

establishment size. Note that in these data, multiple smaller

establishments with common ownership under parent rms

can be reported as individual establishments with 1–49 em-

ployees, whereas in BED data discussed above, those estab-

lishments would be aggregated as one larger rm.

FIGURE 5

Employment Contribution by Firm Size (Truncated Scale)

Net employment flows (in millions)

Expansions less Contractions (1-49 employees)

Expansions less Contractions (50+ employees)

Openings less Closings (1-49 employees)

Openings less Closings (50+ employees)

-4

-2

0

2

4

1997 1999 2001 2003 2005 2007 2009 2011 2013 2015 2017 2019 2021

-10.5m

-3.6m

-0.1m

-1.1m

Total: -15.3m

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Net quarterly employment ows, split by size of rm, are consolidated into two groups: “Expansions less Con-

tractions” refers to the net of employment gained at expanding rms, minus employment lost from contracting rms

“Openings less Closings” refers to employment gained at reopening and newly created rms, minus employment lost

from rms closing either permanently or temporarily. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray shading indicates recession

periods. Employment ows in 2020Q2 are not shown to scale.

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 7

Initially, the smallest establishments bore the brunt of

the employment downturn, losing 56 percent of the total

17.9 million cumulatively lost jobs from January through

April 2020.

5

When considered in conjunction with the data

on rm size shown in Figure 4, an outsize number of job

losses appears to have come from smaller establishments

with common ownership under larger rms. In JOLTS data,

those smaller establishments have also been faster than

larger establishments to recover employment; this suggests

a high rate of hiring by those businesses, some of which was

likely enabled by larger parent rms.

Seen in Figure 6b, available job openings are histori-

cally high across all sizes of establishments. And while it is

true that the smallest businesses typically account for a large

share of job openings, the nearly 5million postings shown

in June 2022 are particularly striking given the apparent

recovery of employment among those smallest businesses.

5. e JOLTS methodology assigns establishment size classes according to the

maximum employment of surveyed businesses over the previous 12months.

is classication remains xed for a year until the next annual sample is

drawn. is diers from other sources of monthly employment by establish-

ment size, including ADP, which captures employment sizes in monthly

survey periods and weights employment by industry and size based on

interpolations of annual employment-share benchmarks. For this reason,

we present JOLTS data as our preferred proxy of employment change across

initial establishment sizes.

Of interest will be how hiring trends continue across busi-

ness sizes, since openings seem to have recently fallen most

among establishments with 50 or more workers.

Growth in New Business

Creation

Applications to start new businesses took o almost imme-

diately at the beginning of the pandemic, reaching 4.4mil-

lion new business applications led in 2020, almost 900,000

more than had been led in 2019. In all, from the start of

2020 through June 2022, total applications for new busi-

nesses are up almost 40 percent over pre-pandemic trend,

while those that the Census Bureau deems as high propen-

sity, or likely to result in an employer business, are nearly

30percent higher.

6

rough 2021 those applications appear

6. We focus on high-propensity applications of likely employer businesses

because these correspond more closely to the measure of establishment

births in BED data. Applications for likely non-employer businesses, such

as sole proprietorships, have also been elevated since 2020. However, those

applications provide less of a signal for future economic growth and can

be inuenced by factors such as tax policy. For example, some researchers

explore whether non-employer applications were boosted by people looking

to qualify for benets provided by the Paycheck Protection Program, although

those researchers nd what was at most a modest eect. For discussion, see

Haltiwanger (2022) and Bungton et al. (2021).

FIGURE 6

Cumulative Employment and Job Openings by Establishment Size

A. Employment Change Relative to February 2020 B. Job Openings Relative to History

Feb.

2020

Sep.

2020

Apr.

2021

Nov.

2021

Jun.

2022

Employment change (in millions)

2000 2003 2006 2008 2011 2014 2016 2019 202

2

Job openings (in millions)

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

1 to 49 employees

50 to 249

employees

250+ employees

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1 to 49 employees

50 to 249 employees

250+ employees

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (BLS-JOLTS) 2022; authors’ calculations.

Note: Panel A shows cumulative employment changes from February 2020 through June 2022 by establishment em-

ployment size, where monthly changes in employment are measured as hiring net of total separations. Panel B shows

the full JOLTS timeseries of job openings across establishment sizes beginning in December 2000 and running through

June 2022. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray shading indicates recession periods.

8 The Hamilton Project • Brookings

to have translated to near-record levels of business creation.

Figure 7 plots high-propensity business applications against

establishment births by industry, each relative to their 2018–

19 trend, cumulating those numbers from the second half of

2020 through 2021.

7

New business applications among the most pandemic-

aected service industries have risen more than actual es-

tablishment births. Across leisure and hospitality, retail, and

other generally personal services, high-propensity applica-

tions from the third quarter of 2020 through 2021 were cu-

mulatively 41percent over pre-pandemic trends, while es-

tablishment births were only 9 percent above trend. To be

sure, the opening of a new employer business typically lags

7. Note that BFS high-propensity applications are based on characteristics for

new rms, while BED measures births of establishments, which can include

new establishments created by existing rms. We rely on BED data for its

timeliness; the most recent data release covers 2021Q4 at the time of publica-

tion. e Census Bureau’s Business Dynamics Statistics is the primary admin-

istrative data source for rm-level dynamics, but is released on a signicant

lag and available only through 2019. Haltiwanger (2022) shows the cumulative

impulse response to an innovation in high-propensity applications on estab-

lishment births to be signicant and increasing through 12 quarters.

an application, and births may still yet rise strongly in com-

ing quarters.

In contrast, applications in the industries of informa-

tion, transportation and warehousing, and professional and

businesses services have more quickly translated to elevat-

ed business creation. ose applications were a cumulative

49percent above trend and had resulted in 27percent more

establishment births by the end of 2021. ese represent a

large portion of business activity responding to new op-

portunities amid the pandemic, as demand rose for certain

business services, logistics, and technologies as people and

rms quickly shied to a remote environment.

e industry composition of new business applica-

tions also changed over the course of the pandemic. Early

on, applications for new businesses were tilted toward the

most pandemic-aected service industries, with high-pro-

pensity applications 45percent above trend from mid-2020

through mid-2021. However, applications ultimately trailed

o in these industries, falling to 29 percent above trend from

mid-2021 to mid-2022. Meanwhile applications in infor-

mation, transportation and warehousing, and professional

FIGURE 7

Comparing the Increase in Establishment Births to High-Propensity

Business Applications, 2020Q3–2021Q4

Construction

Education and health

Financial activities

Information

Leisure and hospitality

Manufacturing

Natural resources and mining

Other services

Professional and business services

Retail trade

Transportation and warehousing

Wholesale trade

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

Percent increase in establishment births

(relative to trend)

Percent increase in high-propensity business applications (relative to trend)

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 2018-2021; Census Bureau, Business

Formation Statistics (Census-BFS) 2018–2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Plotted on the y-axis is the percentage increase in the total number of establishment births from 2020Q3 to

2021Q4 relative to what would have occurred if births had continued at 2018Q1 to 2019Q4 trend rates. Similarly, plot-

ted on the x-axis is the percentage increase in the total number of recent high-propensity business applications relative

to the 2018Q1 to 2019Q4 trend.

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 9

and businesses services—a group more oriented around the

changes brought about by remote work—have continued to

increase, rising from 47percent above trend through mid-

2021 to 49percent above trend in the most recent period.

Underlying this shi may be changing motivations of

new entrepreneurs. A survey of new business owners from

Gusto (a payroll and human-resources platform) found that

35 percent of new business owners in 2020 cited previous

job layos as their top reason for starting a business. at is

consistent with previous business cycles during which busi-

ness creation accelerated toward the end of economic down-

turns as labor market opportunities remained constrained.

Similarly, early research has shown greater business forma-

tion in 2020 in states that faced greater job loss (Djankov

and Zhang 2021). By 2021, however, only 14percent of new

business owners cited previous job layos as their top rea-

son for starting a business, while roughly 25percent cited

pandemic-related business opportunities as their motiva-

tion (Pardue 2022).

Many of these recently created employer businesses also

appear to be somewhat smaller in size than new births in

2018 and 2019. Figure 8 compares employment per birth

ratios of recently created establishments to pre-pandemic

ratios. ese data suggest that newly created businesses are

beginning with fewer employees in all industries except for

transportation and warehousing. Although information

businesses registered record high establishment births that

far exceeded even the boom in this sector in the Dot Com

run-up, the average of 2.1 jobs created per birth was signi-

cantly below the average of 2.7 from 2018 and 2019. Simi-

larly, new businesses in leisure and hospitality and retail

trade are smaller on average by 1.7 and 0.8 workers, respec-

tively. ese results so far t the historical picture of new

businesses born in recession periods, which tend to remain

smaller and hire fewer employees over their lives (Sedláček

and Sterk 2017). In contrast, hiring at new manufacturing

and construction establishments has been much closer to

pre-pandemic rates through 2021.

Conclusion

e relatively quick rebound of the business sector was

due in large part to the unique nature of the COVID reces-

sion, with its abrupt shutdown and then reopening of the

FIGURE 8

Ratio of Employment per Establishment Birth by Industry, 2020Q3–2021Q4

Compared to Pre-Pandemic

Pre-pandemic: Employment per birth

Construction

Education and health

Financial activities

Information

Leisure and hospitality

Manufacturing

Natural resources and mining

Other services

Professional and business services

Retail trade

Transportation and warehousing

Wholesale trade

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0

5.0

6.0

7.0

8.0

1.0 2.0 3.0 4.0 5.0 6.0 7.0 8.0 9.0 10.0

COVID Recovery: Employment per birth

45⁰ Slope

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 2018-2021; authors’ calculations.

Note: Plotted on the y-axis is the ratio of gross employment created by establishment births divided by the number

of establishment births measured cumulatively from 2020Q3 to 2021Q4. Similarly, plotted on the x-axis is the ratio of

gross employment per establishment birth measured cumulatively from 2018Q1 to 2019Q4. Industries beneath the

45-degree line indicate smaller employment per birth in the recent period than in the pre-pandemic period.

10 The Hamilton Project • Brookings

economy. Aer an unprecedented number of businesses

temporarily shut down in 2020, a majority were able to re-

open in the year that followed. Since that time, the pace of

new business formation has exceeded any period in recent

memory and has helped propel the recoveries in employ-

ment and in the number of active establishments. is re-

port nds that the recovery of the business sector overall

masks considerable restructuring of business activities, both

among service-sector industries that were most exposed to

early COVID lockdowns and among industries responding

to new demand for certain products and services amid the

pandemic. e implications of these dynamics for future

job creation and productivity growth are unclear and will

depend on whether the new businesses, given their focus

and structure, remain viable as the economy continues to

recover.

e role of policy supports during the COVID period

also bears emphasis. Enormous scal support for house-

holds in 2020 and 2021 through expanded unemployment

insurance and checks to households helped to support con-

sumer demand and make business creation possible (Fazio

et al. 2021; Ganong et al. 2022; Gelman and Stephens 2022).

In contrast, evidence of the ecacy of pandemic business-

support programs, including the Paycheck Protection Pro-

gram, is mixed. A review of those programs nds that most

support went to businesses that would not have changed

employment even in the absence of the program. Much of

the same impact on business survival could have been ac-

complished in a more cost-eective manner by better target-

ing businesses that were most in danger of contracting or

failing, which are oen the smallest businesses that lack the

same access to capital that larger rms enjoy (Chodorow-

Reich, Iverson, and Sunderam 2022).

Together, those factors helped to stimulate the business

activity that has helped propel the ongoing recovery from

the COVID recession. Prior to the pandemic, the United

States had experienced decades-long declines across various

measures of business and labor market dynamism. Rates

of business start-ups and the share of employment at those

start-ups had each been cut in half since the mid-1980s,

while worker rm-switching was also at multi-decade lows

(Lettieri and Fikri 2022). Some initially worried that the ex-

pected rise in business exits and slowed rm entry, which

typically accompany economic downturns, would further

worsen competition and business dynamism (Rose 2020).

is report shows how the business sector deed those ex-

pectations and has provided new opportunities for workers

and capital to be redirected toward more-productive and

higher-growth areas.

e Hamilton Project has released multiple policy pro-

posals to foster a more dynamic and productive business

sector, proposals that aim to promote economic growth and

expand economic opportunity. Enhancing healthy compe-

tition across the business sector is central to these policy

goals, since many industries show record levels of concen-

tration among incumbent rms (Shambaugh et al. 2018).

In particular, policymakers should rescind policies that

eectively stie the ability of workers to switch rms and the

ability of new rms to enter markets, such as noncompete

contracts and occupational licensing requirements (Krueger

and Posner 2018; Nunn 2018, 2021). Alleviating these re-

straints boosts productivity and wage growth (Shambaugh,

Nunn, and Liu 2018). As policymakers turn from scal sup-

port to longer-term economic strategy, the implementation

of creative policy ideas to bolster the economy’s dynamic

foundations will both increase economic growth and cause

those gains to be widely shared (Chatterji 2018; Gans 2018;

Moss, Nunn, and Shambaugh 2020).

References

“All Over the Rich World, New Businesses Are Springing to Life.”

2022. e Economist, April 23, 2022.

Bungton, Catherine, Daniel Chapman, Emin Dinlersoz, Lucia

Foster, and John Haltiwanger. 2021. “High-frequency

data from the U.S. Census Bureau during the COVID-19

pandemic: small vs. new businesses.” Business Economics

56: 155–167.

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). 1997-2021. “Business Employ-

ment Dynamics (BED).” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S.

Department of Labor, Washington, DC. Accessed August

5th, 2022.

———. 2022. “Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

(JOLTS).” Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of

Labor, Washington, DC. Accessed August 5th, 2022.

Chatterji, Aaron. 2018. “e Main Street Fund: Investing in an

Entrepreneurial Economy.” e Hamilton Project, Brook-

ings Institution, Washington, DC.

Chodorow-Reich, Gabriel, Ben Iverson, and Adi Sunderam.

2022. “Lessons Learned from Support to Business during

COVID-19.” e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution,

Washington, DC.

Crane, Leland, Ryan Decker, Aaron Flaaen, Adrian Hamins-Puer-

tolas, and Christopher Kurz. 2022. “Business exit during

the COVID-19 pandemic: Non-traditional measures in

historical context.” Journal of Macroeconomics 72 (103419).

Decker, Ryan, and John Haltiwanger. 2022. “Business entry and

exit in the COVID-19 pandemic: A preliminary look at

ocial data.” FEDS Notes, Board of Governors of the Fed-

eral Reserve System, Washington, DC.

Dinlersoz, Emin, Timothy Dunne, John Haltiwanger, and Veron-

ika Penciakova. 2021. “Business Formation: A Tale of Two

Recessions.” AEA Papers and Proceedings 111: 253–257.

Djankov, Simeon, and Eva Zhang. 2021. “Startups in the United

States during the pandemic reect some dynamism amid

job losses.” Policy Brief, Peterson Institute for Interna-

tional Economics, Washington, DC.

Fazio, Catherine, Jorge Guzman, Yupeng Liu, and Scott Stern.

2021. “How is COVID Changing the Geography of

Entrepreneurship? Evidence from the Startup Cartogra-

phy Project.” Working Paper 28787, National Bureau of

Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Ganong, Peter, Fiona Greig, Pascal Noel, Daniel M. Sullivan, and

Joseph Vavra. 2022. “Lessons Learned from Expanded

Unemployment Insurance During COVID-19.” e Ham-

ilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Tracking the Robust Recovery in the Business Sector Since 2020 11

Gans, Joshua. 2018. “Enhancing Competition with Data and

Identity Portability.” e Hamilton Project, Brookings

Institution, Washington, DC.

Gelman, Michael, and Melvin Stephens Jr. 2022. “Lessons Learned

from Economic Impact Payments During COVID-19.” e

Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Haltiwanger, John. 2022. “Entrepreneurship during the CO-

VID-19 Pandemic: Evidence from the Business Formation

Statistics.” In Entrepreneurship and Innovation Policy and

the Economy, Volume 1, edited by Josh Lerner and Scott

Stern. 9-42. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Krueger, Alan, and Eric Posner. 2018. “A Proposal for Protecting

Low-Income Workers from Monopsony and Collusion.”

e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washing-

ton, DC.

Lettieri, John, and Kenan Fikri. 2022. “e Case for Economic

Dynamism and Why It Matters for the American Work-

er.” Economic Innovation Group, Washington, DC.

Moss, Emily, Ryan Nunn, and Jay Shambaugh. 2020. “e

Slowdown in Productivity Growth and Policies at Can

Restore It.” e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution,

Washington, DC.

Nunn, Ryan. 2018. “How Occupational Licensing Matters for

Wages and Careers.” e Hamilton Project, Brookings

Institution, Washington, DC.

———. 2021. “Removing Policy Obstacles to Competitive Labor

Markets.” Blog. e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institu-

tion, Washington, DC. July 13, 2021.

Pardue, Luke. 2022. “Survey: Entrepreneurs Seizing New Business

Opportunities Amid the Great Resignation.” Company

News. Gusto, Washington, DC. June 23, 2022.

Rose, Nancy. 2020. “Will Competition Be Another COVID-19

Casualty?” e Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution,

Washington, DC.

Sedláček, Pter, and Vincent Sterk. 2017. “e Growth Potential of

Startups over the Business Cycle.” American Economic

Review 107 (10): 3182-3210.

Shambaugh, Jay, Ryan Nunn, Audrey Breitwieser, and Patrick Liu.

2018. “e State of Competition and Dynamism: Facts

about Concentration, Start-Ups, and Related Policies.” e

Hamilton Project, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Shambaugh, Jay, Ryan Nunn, and Patrick Liu. 2018. “How Declin-

ing Dynamism Aects Wages.” e Hamilton Project,

Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

US Census Bureau. 2018–22. “Business Formation Statistics

(BFS).” US Census Bureau, Suitland, MD. Accessed Au-

gust 2nd, 2022.

———. 2020. “Small Business Pulse Survey.” US Census Bureau,

Suitland, MD. Accessed August 2nd, 2022.

ADVISORY COUNCIL

STEPHANIE AARONSON

Vice President and Director,

Economic Studies;

Senior Fellow, Economic Studies,

The Brookings Institution

GEORGE A. AKERLOF

University Professor,

Georgetown University

ROGER C. ALTMAN

Founder and Senior Chairman,

Evercore

KAREN L. ANDERSON

Senior Director of Policy & Communications,

Becker Friedman Institute for

Research in Economics,

The University of Chicago

ALAN S. BLINDER

Gordon S. Rentschler Memorial Professor of

Economics and Public Affairs,

Princeton University;

Nonresident Senior Fellow,

The Brookings Institution

STEVEN A. DENNING

Chairman,

General Atlantic

JOHN M. DEUTCH

Institute Professor,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

CHRISTOPHER EDLEY, JR.

Co-Founder and President Emeritus,

The Opportunity Institute

BLAIR W. EFFRON

Partner,

Centerview Partners LLC

DOUGLAS W. ELMENDORF

Dean and Don K. Price Professor of

Public Policy,

Harvard Kennedy School

JUDY FEDER

Professor and Former Dean,

McCourt School of Public Policy,

Georgetown University

JASON FURMAN

Aetna Professor of the Practice of

Economic Policy, Harvard University;

Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for

International Economics;

Senior Counselor, The Hamilton Project

MARK T. GALLOGLY

Cofounder and Managing Principal,

Centerbridge Partners, L.P.

TED GAYER

President,

Niskanen Center

TIMOTHY F. GEITHNER

President, Warburg Pincus;

Senior Counselor, The Hamilton Project

ROBERT GREENSTEIN

Visiting Fellow, The Hamilton Project,

Economic Studies, The Brookings Institution;

Founder and President,

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

MICHAEL GREENSTONE

Milton Friedman Professor in

Economics and the College,

Director of the Becker Friedman Institute for

Research in Economics, and

Director of the Energy Policy Institute,

University of Chicago

GLENN H. HUTCHINS

Chairman, North Island and

North Island Ventures

LAWRENCE F. KATZ

Elisabeth Allison Professor of Economics,

Harvard University

MELISSA S. KEARNEY

Neil Moskowitz Professor of Economics,

University of Maryland;

Director, Aspen Economic Strategy Group;

Nonresident Senior Fellow,

The Brookings Institution

LILI LYNTON

Founding Partner,

Boulud Restaurant Group

HOWARD S. MARKS

Co-Chairman,

Oaktree Capital Management, L.P.

KRISTON MCINTOSH

Managing Director,

Hamilton Place Strategies

ERIC MINDICH

Founder,

Everblue Management

DAMBISA MOYO

Co-Principal,

Versaca Investments

SUZANNE NORA JOHNSON

Former Vice Chairman,

Goldman Sachs Group, Inc.;

Co-Chair,

The Brookings Institution

PETER ORSZAG

CEO, Financial Advisory,

Lazard Freres & Co LLC

RICHARD PERRY

Managing Partner & Chief Executive Ofcer,

Perry Capital

PENNY PRITZKER

Chairman and Founder, PSP Partners;

38th Secretary of Commerce

MEEGHAN PRUNTY

Principal,

PE Strategic Partners

ROBERT D. REISCHAUER

Distinguished Institute Fellowand

President Emeritus,

Urban Institute

NANCY L. ROSE

Charles P. Kindleberger Professor of

Applied Economics,

Massachusetts Institute of Technology

DAVID M. RUBENSTEIN

Co-Founder and Co-Chairman,

The Carlyle Group

ROBERT E. RUBIN

Former U.S. Treasury Secretary;

Co-Chair Emeritus,

Council on Foreign Relations

LESLIE B. SAMUELS

Senior Counsel,

Cleary Gottlieb Steen and Hamilton LLP

SHERYL SANDBERG

Chief Operating Ofcer,

Facebook

DIANE WHITMORE SCHANZENBACH

Margaret Walker Alexander Professor and

Director, The Institute for Policy Research,

Northwestern University;

Nonresident Senior Fellow,

The Brookings Institution

STEPHEN SCHERR

Chief Executive Ofcer,

Goldman Sachs Bank USA

RALPH L. SCHLOSSTEIN

President and Chief Executive Ofcer,

Evercore

ERIC SCHMIDT

Former CEO and Chariman, Google;

Co-Founder, Schmidt Futures

ERIC SCHWARTZ

Chairman and CEO,

76 West Holdings

JAY SHAMBAUGH

Professor of Economics and International Affairs,

The George Washington University

THOMAS F. STEYER

Business Leader and Philanthropist;

Founder,

NextGen America

MICHAEL R. STRAIN

Director of Economic Policy Studies and

Arthur F. Burns Scholar in Political Economy,

American Enterprise Institute

LAWRENCE H. SUMMERS

Charles W. Eliot University Professor,

Harvard University

LAURA D’ANDREA TYSON

Distinguished Professor of the Graduate School,

University of California, Berkeley

DAVID WEIL

Co-President,

Charles and Lynn Schusterman Family

Philanthropies

WENDY EDELBERG

Director

WWW.HAMILTONPROJECT.ORG

1775 Massachusetts Ave., NW

Washington, DC 20036

(202) 797-6484

Printed on recycled paper.

Establishment Deaths and Births Relative to Temporary Shutdowns

and Reopenings

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021

Number of establishments

(in thousands)

Number of establishments

(in thousands)

Establishment

births

Establishment

deaths

Temporary shutdowns

Reopenings

20

30

40

50

60

70

1997 2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018 2021

A. Service Sector

B. Goods Sector

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Business Employment Dynamics (BLS-BED) 1997-2021; authors’ calcula-

tions.

Note: Figures present quarterly data for the number of establishment births and reopenings through the end

of 2021. Data on establishment deaths and temporary shutdowns are available only through 2021Q1 due to

lagged reclassica tion of “total closings,” which are not shown. All data are seasonally adjusted. Gray shading

indicates recession periods. Y-axes for services and goods sectors are shown at different scales.

A Hamilton Project analysis of the business sector over the COVID-19 period nds that, despite initial fears of

widespread failure, existing businesses and new entrepreneurship have deed earlier expectations, ending 2021

with nearly 450,000 more establishments in operation than prior to the pandemic.

Underneath these aggregate results, patterns across industries reveal evidence of considerable economic

restructuring. A large share of new business creation has occurred in the industries most exposed to the pan-

demic downturn, primarily face-to-face services like restaurants. Other new business activity, such as online

retail and data services, reect new opportunities in the transition to a more remote environment. is report

also traces the employment implications of this churn to uncover the impacts of initial employment losses and

recent recovery across businesses of varying sizes. While questions remain around the contribution of these

new dynamics to job creation and productivity, the persistence of these shis and the resiliency of small busi-

nesses will play key roles in determining the path of the recovery moving forward.