The Court Reporter by

Harry M. Scharf

(One-time Careers Officer, Institute of Shorthand Writers.)

as

published in

The Journal of Legal History

September 1989

This article is copied by the British Institute of Verbatim Reporters with the kind

permission of both Harry Scharf and the original publishers, as noted here:

18/02/2003 via e-mail

"We are pleased to grant you permission to use the article, free of

charge, provided you grant acknowledgement of its source.

Amna Whiston Publicity & Rights Executive Frank Cass Publishers"

We have reformatted it to fit the web page, omitting the original page numbers.

However, the BIVR cannot accept responsibility for the accuracy of any of the

information contained therein.

I Background

In 1588 Dr. Timothy Bright published the first book in England on a shorthand

system, which he termed a 'Characterie'. The following year he was granted

a 15-year patent monopoly of publishing books on this system (See Appendixl).

1

This was followed in 1590 by a work by Peter Bales called a 'Brachygraphy' from

the Greek for shorthand. The object was to produce a verbatim simultaneous

account.

These publications preceded similar publication in the contemporary Europe. This

may therefore be a good occasion to celebrate the centenary of a striking

development which must have influenced law-reporting and the requirements of

the modern system of judicial precedent.

As law-reporters we are primarily concerned with the use of methods of

perpetuating the oral elements in legal proceedings. These range from obscure

mnemonic and idiosyncratic jottings which had to be quickly extended by their

authors to complete contemporary accounts of all that was said. The need for the

latter extreme might only exist where the ipsissima verba were required, not

merely the broad underlying sense of arguments and decisions, which for most

lawyers sufficed or was even preferable to too much detail.

That some form of abbreviation was essential in forensic matters appears to have

been realised quite early. Tiro Tullius, a freedman of M.T. Cicero, invented a kind

of shorthand system under the Roman Republic. Cicero studied law under the

eminent jurist Mucius Scaevola and acted as 'counsel' at trials. His recorded

speeches are also a valuable source for the study of Roman law of his time.

L. A. Seneca practised law under the Emperor Caligula and produced a further

shorthand system.

2

He had to abandon his practice because of the Emperor's

envy of his talent and resort to more retired pursuits. Augustus himself used

shorthand. Suetonius, who was a contemporary of the Emperor Titus, states that

the Emperor was very proficient in the art of shorthand.

During the mediaeval period in England a kind of speedwriting was used on the

Latin plea rolls (e.g. bre for breve, Reg' for Regis). In the Law French of the Year

Books a similar method of conventional abbreviation was used (e.g. coe for

commune, jug' for Jugemet and nr for nostre). The plea roll record was made up

after the court hearing and the Year Book MSS were written up from rough

jottings made in court.

In the late sixteenth century Sir James Dyer was Chief Justice of the Court of

Common Pleas from 1559 to 1582. According to Lord Campbell Dyer used

shorthand notes, while he studied for the Bar in the 1530s, of arguments and

judgments in Westminster Hall, which he then 'digested and abridged into a lucid

report of each case'.

3

These notes were obviously not intended for strange eyes

and must have been aided by memory. However they must have given him an

advantage over longhand reporters. After his elevation to the judicial Bench he

continued to make notes of cases tried in his court and these were used in editing

his well-known Reports which were published after his death but had been

prepared for publication.

Sir Edward Coke seems not to have used shorthand, but he enjoyed a particular

skill in summing up cases for his own use 'since 22 Elizabeth I' and says he let

friends consult them. Coke professed to give a summary account of the effect of

what was said in court, 'beginning with the objections and concluding with the

judgment of the court'.

4

Such precis-writing by a master was valuable but still

lends itself to afterthoughts and ornamentation and possible distortion in partisan

matters.

Knowledge of shorthand grew quickly in the early seventeenth century. John

Willis's system of 1602 led to further refinements by Thomas Shelton in 1630,

and Shehon's system became especially popular.

It is generally believed that some of the early pirated editions of Shakespeare's

plays owed a debt to shorthand. It is thought that members of the audience and

actors at the side of the stage may have prepared some of these, and in the case

of his plays literal exactitude was more important than broad and unoriginal story

lines.

Samuel Pepys is known to have used Shelton's system in his famous Diary.

5

He is

believed to have taken notes at the 'Popish Plot' trials in 1684 and his transcript

was more accurate than the printed reports.

6

A few years later a Mr. Blaney is reported as having made a shorthand account of

the Trial of the Seven Bishops in June 1688 and of the debate of 6 February 1689

in Parliament

7

By 1700 shorthand was being widely practised. In 1742 John

Byrom M.A. secured an Act of Parliament giving him a monopoly for 21 years of a

system of shorthand devised by him, as a 'useful art' not protected by the

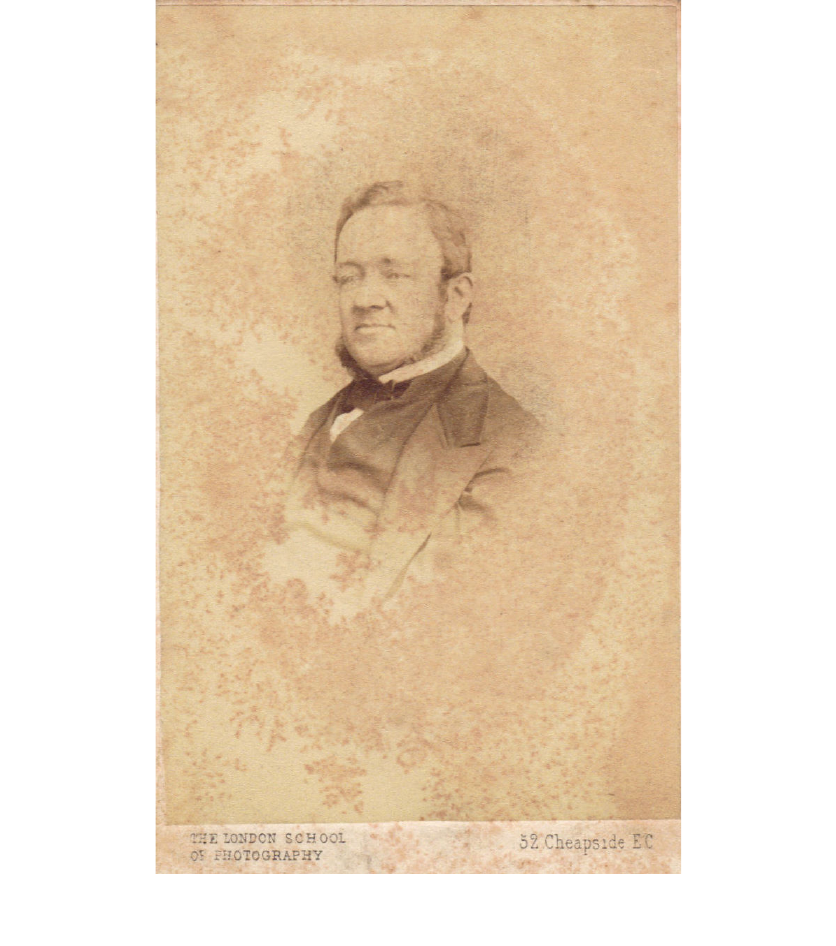

existing law (see Plate 1).

Plate 1

Modern research has shown the interest of the shorthand diary of Sir Dudley

Ryder, Attorney General and later (1754) Lord Chief Justice of the King's Bench.

Like Dyer he had learned shorthand, a system similar to that of Jeremiah Rich,

while still a law student. He continued to use it during his career and as a judge

when trying civil and criminal cases. Since there is a relative paucity of material

on criminal trials, his notes from the sessions of the Old Bailey provide

information not included in the printed reports in the Old Bailey Sessions Papers.

9

Thus he notes his own directions to the jury and summings up and adds personal

observations on the verdicts.

10

Transcripts of shorthand also had important official uses after the trial was over.

There was no regular system of appeals so that a transcript was not needed for

that purpose. On the other hand it was the practice to obtain transcripts of cases

if they had resulted in capital convictions and transmit these as quickly as

possible to the Crown for use in deciding whether to exercise the prerogative of

mercy.

11

There were also cases where the fact of bringing a criminal prosecution was

a relevant matter in a subsequent civil case. The shorthand reporter could be

called to authenticate his transcript of his 'minutes'.

12

In 1758 John Angell, Sr. wrote a book called Stenography or Shorthand

improved, based on 30 years' experience. His son later brought out three editions

of this work. He was an official shorthand writer in Ireland and a teacher of

shorthand in Dublin. It was the son who challenged Dr. Samuel Johnson by

claiming that he could take down speech as quickly as he spoke, a task which he

failed to perform although Johnson took care to speak fairly slowly.

13

Boswell had himself practised law in Edinburgh about 1767.

14

In his Life of

Johnson Boswell pointed out that he himself did not use 'what is called

stenography or shorthand in appropriate characters devised for 'he purpose.

I had a method of my own of writing half-words and leaving out some altogether,

so as yet to keep the substance and language of any discourse.'

15

This must, by

language, mean the style rather than the exact words, Boswell did not record his

Life of Johnson simultaneously with Johnson's speeches. He gives an illuminating

jxample. His note on one conversation had been as follows:

Johns. Walt great Panegyr. Bos. no qual will get more friends than admir - not

flattery. Johns. Yes flat, please 1st man thinks so 2. Thinks us of conseq, to say

so.

16

We can compare this with the orotund periods of the published version for 18

April 1775:

J. He supposed that Walton had then given up his business as a linen draper and

sempster and was only an author, and added, that he was a great panegyrist.

Boswell. No quality will get a man more friends man a disposition to admire the

qualities of others. I do not mean flattery but a sincere admiration. Johnson.

Nay, Sir, flattery pleases very generally. In the first place the flatterer may think

what he says to be true: but in the second place, whether he thinks so or not he

certainly thinks those whom he flatters of consequence enough to be flattered.

17

It may be useful to point out that from 1834 Parliament encouraged shorthand

writers to be present to report debates.

18

A ms shorthand note, described as a 'whole minute', was taken of the noted

Somerset's case in 1772 on the status of slaves brought to England. The

published reports of the proceedings differ among themselves in several respects;

they were clearly not themselves taken down exactly and suffer accordingly. One

William Blanchard who produced works on shorthand in 1779 and 1786 enjoyed

Lord Mansfield's patronage. The reporter Joseph Gurney took full notes at all the

150 sessions of the trial of Warren Hastings in 1785. Great American Presidents

at the turn of the century, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison, were known to

have used shorthand.

19

The value of shorthand in legal reporting obviously depended on the presence or

absence of a need to report things verbatim. Medieval reporting is limited to

a brief summary of argument in the Year Books with some but not all judgments

reported. Appeals based on error in the record would be based on the short and

formal contents of the record. When the procedure by motion for new trial

developed in the eighteenth century the trial judge would supply a report based

on his own notes, which might be substantial but incomplete, prepared to help

him draft his own judgment, and taken down in longhand in most cases. In courts

where evidence was taken down in pre-trial depositions there would also be less

need for exact reporting, e.g. the Chancery and Admiralty.

Lord Campbell, L.C.J, had been a Parliamentary reporter at the beginning of the

nineteenth century and in 1807 became a law reporter of cases tried at Nisi Prius.

He would not leam shorthand, though it was now in common use by some

reporters. He also edited and re-wrote the reports from his longhand notes and

claimed that these were an improvement.

20

The eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were the heyday of the great Gumey

'dynasty' of shorthand reporters. Thomas Gumey became a shorthand reporter at

the Old Bailey for several years before his official appointment as shorthand

writer in 1748, believed to be the first such official appointment recorded

anywhere in the world. He also took notes in the House of Commons and in all

the courts. He used his verbatim court reports to publish accounts of some of the

great trials which he attended and attracted popular interest. His son Joseph was

appointed official reporter in the civil courts in 1790 and also reported

proceedings in Parliament. In turn he published accounts of notorious cases. W.B.

Gumey, a grandson of Thomas Gumey, was officially appointed shorthand writer

to the Houses of Parliament in 1813. He also practised his art in the courts and,

among others, reported the trial of Queen Caroline in 1820.

21

W.B. Gurney has been immortalised in a sense by Lord Byron, in stanza 189 of

the first canto of his great poem 'Don Juan' published in 1819.

If you would like to see the whole proceedings

The deposition and the cause in full,

The names of all the witnesses, the pleadings,

Of counsel to nonsuit or to annul,

There's more than one edition, and the readings

Are various, but they none cof them are dull,

The best is that in shorthand ta'en by Gumey,

Who to Madrid on purpose made a journey.

22

Our most famous court reporter in Parliament and the courts was Charles

Dickens. He had worked for a firm of solicitors. From 1829 to 1831 he reported

proceedings at Doctors' Commons, using shorthand. His experience of

ecclesiastical court proceedings produced an account of a supposed case of

Bumple v Sludberry in Sketches by Boz in 1835. This was concerned with a

dispute over a church and he attacked the then Judge, Dr.Phillimore, Regius

Professor of Civil Law at Oxford, in this lampoon. He also reported from Chancery,

the Old Bailey and Bow Street Magistrates' Court. An imaginary common law

proceeding for breach of promise, Bardell v Pickwick, figures in the Pickwick

Papers published in 1836, with the immortal caricatures of Serjeant Buzfuz as

counsel and the firm of Dodson Fogg as attorneys. An Old Bailey trial of Fagin

appears in Oliver Twist in 1838. Delays in Chancery were featured in Bleak House

in 1852, with its interminable case of Jarndyce v Jarndyce.

2

*

George Borrow was articled to a Norwich firm of solicitors from 1819 to 1824

when he moved to London. In 1825 he edited a book called Celebrated Trials

which drew on Howell's great series of State Trials and on the so-called Newgate

Calendar which was produced unofficially from 1773 at various dates and

probably inspired many of the authors of those days with dramatic plots. Borrow

was apparently involved in some issues, presumably in the Calendar for 1824-6.

There is evidence that Borrow tried unsuccessfully to be appointed a magistrate.

24

The Gurney family of court reporters were distant relatives of the great Quaker

banking family of Gurneys who flourished in the mid-nineteenth century.

25

In

1875 W.S. Gilbert alludes to them in the Judge's song in 'Trial by Jury*.

At length I became as rich as the Gurneys.

An incubus then I thought her.

So I threw over that rich attorney's

Elderly ugly daughter.

26

The adaptation of shorthand to use in court reporting led to the further

improvement of devising especially short designs to express common legal terms

of ait. These were variously called abbreviations, arbitraries, short forms and

grammalogues. They are not generally completely arbitrary but simplified or

abbreviated versions of the normal patterns. In 1815 A.W. Stone offered a few

samples, e.g. for 'defendant' and 'judgment'. In 1836 I.A. Nelson's book also

suggested a few contractions for shorthand in forensic work. In 1840 G. Eyre,

a solicitor, devised a system of shorthand especially designed for the writing of

legal expressions.

27

In modern times such short forms are generally offered by popular shorthand

systems for use in court reporting work. Thus a Gregg Reporting Course

published in the United States in 1936 provided short forms for a number of

common legal expressions, such as 'beyond reasonable doubt', 'find a verdict

according to the evidence', and 'contributory negligence'.

Individual reporters can devise their personal variations for particular phrases

they encounter in their specialised areas. There is, however, some advantage in

using a recognised system if there is any likelihood that the shorthand might

have to be transcribed by a different reporter, e.g. after some lapse of time.

28

II Organisation of Shorthand Writers

During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries shorthand writers had practised

their art as individuals and without any sort of representative body to look after

their interests. They were employed as required by parties to actions in the

courts, and Parliament had various people recording their proceedings, after a

fashion. A petition to Parliament was raised requesting an inquiry into the

practice of shorthand reporting with a view to recognising it as a profession.

In 1849 the first successful attempt was made at forming such a body, which

came to be known as The Society of Practising Shorthand Writers. On 29 June

1850 its constitution was adopted.

At this time there were 33 shorthand writers, and 19 of them were mentioned in

the Law List. Together with another six they became the 25 pioneers, among

whose names will be recognised the names of firms which are still practising

today. They were Messrs. James Drover Barnett, Angelo Bennett, Charles

Bennett, George Cherer, Joseph Nelson Cherer, William Cocks, John Cooke,

C. Leopold Corfield, William Counsell, William Farmer, Henry Gregory, William

Hibbit, J.G. Hodges, F. Bond Hughes, Fleming M. Leathern, George Sedgwick,

George B. Snell, Snr., J. Stratford, Robert H. Tolcher, William Treadwell, Francis

N. Walsh, Robert Walton, Henry White, James White, and Frederick Williams.

Whatever work was done by this Society, there are only faint traces of it. Its main

work was a document called, rather grandly, 'The Case of Practising Shorthand

Writers in reference to the Publication of an Official Record of Parliament, Debates

&c, 1849’. It was produced in response to complaints' of the inaccuracy of the

reports of Parliamentary proceedings in The Times, and it was considered

essential by Lord Beaumont (talking to his peers) that an accurate record should

be made available. Apparently, an official record had already been produced in

the French Legislative Assemblies so the French were ahead of us - in this respect

at least.

An argument then, which is familiar to us today, was that there was a desire for

employment by the State rather than for being privately employed. Until the Cass

Report was published, and put into effect in 1980, many practitioners felt that

was the way out of the abyss of low pay and poor conditions which existed.

There is not much material available on which to found a knowledge of the

Society as to its birth, life or death, but it is thought that it passed away

peacefully about 1851 after, but not because, Messrs. Corfield and Walsh

withdrew. George Cherer took the papers of the Society into his control about the

time of its dissolution.

Fourteen years later when a similar society was being formed these papers were

sought but could not be obtained, as Mr. George Cherer had died, and his brother

took the view that they belonged to his deceased brother, so that he could not

hand them over, besides which the keys to the box in which the papers were kept

had disappeared, as have long since the papers themselves.

In October 1851 Edward Morton remarked that the business of the courts could

not be conducted satisfactorily without the assistance of shorthand writers -

a sentiment with which no doubt his colleagues agreed.

The next attempt to form a unified body was short-lived. In May 1865 shorthand

writers gathered together and resolved to form an association of shorthand

writers with the object of securing efficiency, and improving the status of its

members generally. It was the committee of this new body that tried to recover

the papers from Mr. Cherer, as already mentioned. This group (some of whom

had been members of the earlier Society) for the first time called itself the

Institute of Shorthand Writers, and the following were selected as the first

members: Messrs. J. Bullions, W.A. Corfield, W. Counsell, J.G. Hodges, Snr. and

Jnr., J. Hurst, T.E. Wilmot Knight, T.A. Reed, T. Robeson, G.B. Snell, Snr., R.H.

Tolcher, and F.N. Walsh.

In 1865 there were 40 members of whom only 28 signed the roll of members.

A curious feature of this group was its 'silence, secrecy and seclusiveness' (in

Alexander Tremaine Wright's words). They appear to have been very retiring and

eschewed all publicity, but unfortunately their AGM in January 1866 was 'leaked'

to the Press. There was much agitation within the Institute, so much so that it

could not overcome its embarrassment, and it expired.

However, one good thing that it did, according to the report presented to the

1867 AGM, was to indicate its requirements as to accommodation in the new law

courts about to be built. But more of this anon.

Fourteen years of disorganisation caused the writers to realise the need for what

is today called in certain circles 'a show of solidarity'. They moved into action as

a result of a report published in October 1881. This was the Report of

a Committee on Legal Procedure in which it was suggested in its 13th Clause

that, in effect, it would be at the discretion of the judge how payment for

attendance, and transcript, should be made. There is nothing like one's financial

interests to concentrate the mind - whatever Samuel Johnson may have thought

-so within five days of the publication of the Report seven firms of writers met,

and within a fortnight the inevitable committee had been formed to keep an eye

on this ominous Clause 13. By February 1882 the matter had been clarified and

settled to the satisfaction of these gentlemen.

On 4 March 1882, 58 writers attended a general meeting at which 'it was

unanimously resolved that it was desirable that a society or institute of shorthand

writers practising in the High Court of Justice be formed*. It was also resolved

that such formation should be carried out by revival of the 1865 Institute with

such modifications as were thought advisable.

During the life of the 1865 Institute it had been found that not a single assistant

could be induced to become a member, but in the reconstituted Institute every

qualified assistant became a member on the same terms as the principals. The

reason for this was the change found in the relations of principals and assistants.

Until some time after 1867 an assistant was often not permitted to take notes on

his own responsibility but had to pose as an 'improving pupil', while his principal

was ostensibly taking the note, but out of court the whole labour of producing the

transcript was frequently cast upon the assistant at a ridiculously inadequate

remuneration.

During the next 13 years a subject which engaged the early and anxious

attention of the Institute's Council was the grossly inadequate accommodation

provided in the new Courts of Justice, in the Strand. The 1865 Institute had made

repeated urgent representations about it. The father of the then Attorney-

General, Sir R.E. Webster, was sympathetic, but the result was almost inevitable:

nearly the whole of the representations came to nothing. In some of the courts

the seat provided was but a narrow ledge raised a few inches from the floor, the

writing desk being a narrow ledge at a height almost inaccessible to the occupant

of the lower ledge, and the whole contrivance was put down at a spot where the

difficulty of hearing was most acute.

The six suggestions put forward by the Institute were as follows:

(1) four seats, at least, in each court with flat desks not less than 18 ins. wide;

(2) a central situation with reference to the judge, counsel, witnesses and jury;

(3) a sufficient elevation to enable the note-taker to hear distinctly the words of

the judge;

(4) freedom of ingress and egress;

(5) freedom from interruption;

(6) two retiring rooms, one in connection with the Chancery, the other in

connection with the common law courts.

Fortunately, the then Lord Chief Justice (Lord Coleridge), the Master of the Rolls

(Sir George Jessel), Mr. Justice Chitty, and others, realised that adequate

facilities were necessary and so were induced to take an interest, and some

mitigation of the difficulties was obtained. (The then LCJ's interest in the Institute

was a precedent followed by Lord Lane, the present LCJ.) Lord Coleridge was the

first High Court judge to sit at the newly opened Victoria Courts at Birmingham in

July 1891. They had been opened by the Prince and Princess of Wales in the

same month.

While accommodation for note-takers in the various courts had been the subject

of much complaint over the years, members' coats and umbrellas fared better, as

accommodation was provided for them in the law courts in the Strand as early as

1885!

The Houses of Parliament were destroyed by fire in 1834. Rebuilding began six

years later, and provision was made for a reporters gallery.

Four new courts were recently built in the Victoria Courts at Birmingham, which

were described as ‘prestigious’. Comfortable seats were provided which were all

screwed to the floor. (Was it thought someone would actually 'take the chair'?)

The architect had cunningly placed the shorthand writer's chair at such a distance

from the desk (shared with the court clerk, as a result of which all stage-

whispered conversations between the clerk and others were shared by the note-

taker) as to give maximum discomfort. As a result one reporter took the matter

in hand; took his courage in hand; took a screwdriver in hand, removed the

offending chairs and replaced them with free-standing chairs. So far as is known,

no official complaint was ever made.

Following a rule under the Bankruptcy Act 1883, an attempt was made to reduce

by about 30 per cent the charges for shorthand notes. This again demanded

prompt action. By a notice in the Gazette dated 4 February 1884 the relevant rule

was annulled and the shorthand writers' time-honoured charges were practically

re-established.

The first paragraph of the Institute's fifth annual report announced that the

Institute of Shorthand Writers Practising in the Supreme Court of Judicature had

been registered on 20 January 1887. The archives of the Institute contain the

Memorandum & Articles of Association dated 17 January 1887. They were signed

by 11 writers; the last surviving signatory, Mr. A.R. Marten, died in 1917.

Anyone able to write fairly quickly (usually in shorthand) and who has been

provisionally accredited, and has the moral support of a tape recorder, can go

into court and at least give the impression that she (or he) is writing an accurate

note of the proceedings. On Saturday, 26 January 1793 The Times produced an

advertisement which reads like the forerunner of this description. It stated:

A Reporter. Any gentleman who is capable of taking debates in the Houses of

Parliament may find employment by addressing himself at the office of this paper

this day or Monday.

Ninety years later, in 1883, a special general meeting was called to consider the

suggestion that only members of the Institute should be allowed to take notes in

court. The Court of Appeal held in 1889 that the note of a solicitor's clerk was not

acceptable, which went a long way towards recognition of the official note.

A resolution was passed in 1891 that it was inconsistent with the interests of

shorthand writers to allow tradesmen to hold themselves out as shorthand

writers. During the nineteenth century, it appears, it had been quite an

acceptable practice to advertise. The following appears to have been a typical

example, published in 1828:

Oxford Circuit. To the Profession. Mr. J. A. Dowling, Shorthand Writer, 43

Devonshire Street, Queen-square, London, begs to inform the Profession that he

intends to visit the Oxford Circuit permanently, for the purpose of taking down

such cases as may be required by the parties. The charges are as under, and it is

optional on the part of Mr. D's Clients whether they will take a transcript or not.

£ s d

Taking Notes of a Cause

2 2 0

Transcript, per Law Folio of 72 words

0 0 8

Mr. Dowling's lodgings in each of the towns on the Circuit can be ascertained on

application to Christopher Crouch, Porter to the Circuit.

We took ourselves very seriously as a professional organisation. In keeping with

this professionalism the then Lord Chief Justice in 1913 expressed the opinion

that shorthand writers should wear dark clothes, which sounds surprising,

considering that at that time we must have been a conservative lot anyway. Sixty

years later judges were complaining that women were wearing (the) trousers in

court. What would Lord Coleridge have thought of that?

Dictatees in 1918 appeared to have been getting above themselves when they

sought a rise in pay, and were reminded that by using the typewriter they were

producing work so fast that they were able to earn more than the note-takers. To

rub it in, they were accused at the same time of incompetence! In July 1901

there had been set up a National Union of Typists apparently considering itself as

on a par with accountants and other professionals. Times have changed: the

typist is rather lower down the hierarchy.

In the early years qualifications were, rightly, considered of such importance that,

reading between the lines of one annual report, one sees almost a state trial of

Walsh & Sons because they employed an unqualified person. In January 1885

a meeting of the Institute was held to discuss the matter, and it was proposed

that a protest be signed by the members in consequence of which the Council

would write to the firm. The complaint was that a Mr. King had come from

a solicitor's office and had had no training. Walsh's reply was that Mr. King had

never been employed by them, and that the few occasions when he had acted for

them had been of an entirely exceptional character. (What is 'exceptional'? This

sounds like a mitigation in a criminal case.) This explanation was accepted, and

so another crisis was overcome.

A special meeting was held in 1896 to consider having 'official' shorthand writers

in court. In 1902 Marshall Hall M.P. raised the matter, and the reply was that

such an appointment might be of great convenience but that there were

disadvantages, and that it required careful consideration.

It was the passing of the 1907 Criminal Appeal Act that gave shorthand writers

almost their first official position in the Courts. This Act gave convicted persons

a right of appeal, rather than have their cases considered by the Court of Crown

Cases Reserved on points of law, and section 16 made it clear that shorthand

notes of criminal trials were to be taken. Before this, it would appear, notes of

criminal cases were taken only on instruction from solicitors. Often appointments

were given at remote quarter sessions to the local journalist, who perhaps was

not very efficient. These appointments fell into the hands of firms of shorthand

writers. It followed that as firms attended the assizes so work came their way.

Firms then had appointments to circuits and in very recent times there has been

the situation, for example, of Marten Meredith & Co. having the appointment to

the Midland Circuit, and Walsh & Sons having the appointment to the Oxford

Circuit. The circuits joined together, and the firms, coincidentally, joined together

to make a company known as Marten Walsh Cherer Ltd., thus keeping alive the

names of two members of the original 1849 Society.

In 1923 the Law Stationers Society claimed to have made arrangements to take

notes in the High Court and elsewhere in conjunction with the shorthand writers,

which claim was strongly denied.

In May 1931 the Bar Council recommended there should be court shorthand

writers to cover the Royal Courts of Justice. Consequently, an inquiry under

Mr. Justice Atkinson was held, and the Association of Shorthand Writers Ltd. was

the result, being founded in 1938. In the same year the Institute and the

Association set up house at 2 New Court, their present offices, the Institute

having been of no fixed abode for all the years before.

Full transcripts used to be ordered by the Court of Criminal Appeal. However, as

time went by the number of appeals increased considerably, so in 1950 'short

transcripts' were introduced when the appeal was only against sentence.

Before the abolition of hanging the practice in capital cases was that the

shorthand writer would produce a transcript each evening after working in court,

in case there was a conviction, as then the transcript would be required within

a fortnight of sentence being passed. If the defendant was acquitted, work on the

transcript would cease but payment would be made for work already completed.

During the 1970s we had been falling behind in our pay and were getting rather

desperate that something should be done to redress the matter. One of the big

questions was whether we should become civil servants - an idea mooted back in

1908. There was much to support this idea in terms of pensions and a regularly

increased income in keeping with inflation and other union demands, but then we

would have lost our independence, which we have always treasured. The relative

drop in pay, and the consequent failure to recruit staff, led to the setting up of

the Study Group on Verbatim Reporting.

On the subject of pay, it is interesting to see that in April 1909 The People

newspaper asked whether shorthand writers were being paid adequately under

the Criminal Appeal Act, at £1 per day's attendance and 8d per folio (about 3p

today). That writer wondered why shorthand writers did not become civil

servants.

In 1979 the group published its Report (the Cass Report). It was quite lengthy

and studied our profession deeply, coming out in favour of leaving the profession

as an independent entity. The main consequences of the Report were a pay

increase which took us to a level more consistent with the responsibilities and

skills of the job from a level comparable with that of the shorthand-typist, and at

the same time an obligation to accept the Government's wish that we tender for

contracts to the Lord Chancellor's Department.

Tendering involves a four-year re-examination of the costs of running a business

and paring them as much as possible so as to be able to put forward an

acceptable figure in return for which the firms will be offered the appointment

they seek. In wanting to save money, the Government also has in mind the

previous years' performance.

The practice has resulted in under-cutting, and reductions in the salaries of staff.

It has also resulted in bad feelings between firms. In doing work for the Lord

Chancellor's Department - i.e. Crown Court work - firms are not in competition;

indeed they always used to help each other when it came to covering court by

lending staff where necessary." Another result has been an unsettling of staff in

that every four years they do not know for whom they will be working or if they

are going to be in work at all. As a result of the tendering the firm for which they

are at present working may lose the appointment, and the new appointment

holder may not wish to use the existing staff, or the staff may not wish to work

for him. To add insult to injury, the LCD has asked the Institute to suggest ways

in which the tendering procedure can be improved. Is the person about to be

hanged expected to advise the hangman?

The following is a brief roll call of the better known names in the history of the

Institute. Many names will be recognised by the names of the firms which are still

in existence and which were formed so many years ago.

This chronological list is not exhaustive; but even by mentioning the dates when

they died it will bring their bearers to life.

Reed, Thomas Allan original member of the ISW 29.3.1899

Tolcher, Henry Harwin original member of the ISW; 2 x President 10.4.1899

Walsh, Henry Morton original member of the ISW; 3 x President, and Treasurer

19.6.1900

Walsh, Edward Morton original member ISW; 1 x President 26.7.1904

Hibbit, William 1 x President; founded firm 1861 7.4.1905

Sanders, Thomas a freemason; founded firm 1861 14.2.1906

Counsell, Henry Richard 16.8.1908

Meredith, Thomas practised at Leeds 23.6.1909

Snell, George Blagrave original member of ISW; founded firm 1817 31.10.1910

Stammers, Harold William killed leading platoon in a charge 18.8.1916

Hersee, Charles original member of ISW 9.12.1917

Marten, Alfred Richard last surviving signatory of M of A; secretary of ISW; 4 x

President 5.10.1917

Walsh, Alexander Treasurer; 1 x President 17.12.1918

Snell, Thomas founder-member of ISW; youngest son of G.B. Snell: opened

Manchester office 1882 13.4.1922

Towell, James original member of ISW; 2 x President; practised on SW Circuit

6.12.1925

Howard, Sir Ebenezer, OBE 1.5.1928

Walpole, George member from 1881 19.12.1928

Gurney, Salter apptd. to Houses of Parliament 1872; held post till 1913 when

retired.

Called to the Bar at Lincoln's Inn in 1874 but never practised 21.12.1928

Hurst, A. Stone member of ISW from 1903 to 1910 when resigned to practise at

the Bar, Middle Temple 31.5.1928

Lehmann, John William partner with Cherer Bennett & Davies 1913; member of

ISW 1887 21.3.1928

Barnett, CE member of ISW 1882 to 1906 2.1.1930

Sanders, Charles Alfred Treasurer, 1 x President 10.2.1935

Barnett, Edward Thornton original member of ISW; 4 x President; on Council 31

years 25.9.1935

Snell, Charles Darner 9.11.1936

Hersee, Charles Allan 1.8.1938 Humphries, Ernest L. 1.8.1938

Wright, Alexander Tremaine wrote monograph on Shelton, and other books on

shorthand – to whom this writer is indebted.

In July 1982 a cocktail party was held at the Law Society in Chancery Lane to

celebrate the centenary of the Institute. Distinguished persons attended,

including the Lord Chief Justice (Lord Lane), the Master of the Rolls (Lord

Denning), and the Master of the Rolls-designate (Lord Donaldson).

Ill Methods of Writing

While this account is about shorthand writing and the Institute in particular, it

seems appropriate to mention briefly a topic which must be considered of some

relevance: the writing instrument.

Around the third century B.C. a writing brush made from stiff hair was evolved

and writing became a highly developed art. The Egyptians made use of a rush

pen with its ends frayed like a brush. Greeks and Romans sharpened a reed to

a point, which reed pen had to be constantly sharpened like a pencil.

The most common alternative to the reed pen was the stylus, or metal pen. There

is a story pertaining to the Roman period, that students learning the Tironian

shorthand found it so frustrating they killed their teacher by using their styluses.

Medieval monks laboured long and tediously producing their manuscripts: so

tediously that one eighth-century scribe wrote words which may appear to refer

to shorthand-writing:

Be careful with your fingers; don't put them on my writing. You do not know what

it is to write. It is excessive drudgery; it crooks your back, dims your sight, twists

your stomach and sides(!)

It is interesting to note that the word 'pen' comes from the Latin 'penna',

meaning a feather or quill. Tremaine Wright wrote in The Two Angels,

a biography of the shorthand writers:

The early shorthand writer, of course, wrote with quill pens. Of these he carried

into court with him a goodly supply in a leather case, and also an ink bottle in

a metal case covered with leather. Part of the equipment of his chambers was

a proper penknife and a hone, for he had to cut his pens to suit his hand.

As far back as 1795 the lead pencil had been introduced. During the nineteenth

century attempts were being made to improve on the quill, and it was early in

that century that the steel pen came into being.

Of course people tried to improve on what was then an improvement, the idea

being that it would be more convenient to carry the ink in the pen rather than

separately. Throughout the nineteenth century many attempts, which are well

recorded, were made to produce a satisfactory fountain pen. The story goes that

a certain Lewis Edson Waterman, an American, was motivated by the loss of

a contract due to his pen splattering ink over the paper. In time he produced the

first practical model, in 1884, the 'Ideal’. He founded his business in 1884 and

retained the leadership in pen manufacture right up to the 1930s. Recently, in

1984, a French pen company bought out Waterman's.

A Canadian physics teacher provided some competition towards the end of the

nineteenth century. George S. Parker sold fountain pens to his students but they

were unsatisfactory so he decided to try to improve on them. In 1888 he

successfully produced his first pen and then sold this model to his students. At

the turn of the century, of the many pen manufacturers, Waterman and Parker

were the chief rivals.

W.H. Shaeffer, also an American, was a jeweller who developed the lever-filling

pen in 1908. This was very successful so he was able to incorporate his company

in 1913. By 1920 most companies had produced this type of filling device.

A.T. Cross's literature shows that that company began in 1846 in England but

soon moved to America. Cross patented his 'Stylographic' pen in 1878. In this

pen a blunt needle is caused to move back by the writing pressure which in turn

opens a valve mechanism to release the ink. In 1880 Cross patented a pen with

a more conventional nib.

The 1920s brought styling and colour to fountain pens, while the 1930s

streamlined them. In 1941 Parker introduced the '51' model with its hooded nib.

Mont Blanc has been in business in Germany since 1908.

In the late 1940s we saw the introduction of the ball pen which killed off much of

the fountain pen business as it proved more convenient. The ball point pen was

introduced by Reynolds in Chicago, and in Argentina by Biro, a Hungarian.

Another form of writing instrument well known to shorthand writers for

transcription and with a long history is the typewriter. The idea of a machine to

remove the limitations of the pen was in the minds of many men in the early

eighteenth century. The first-ever patent was taken out in 1714. In Michigan,

USA, William Burt produced a 'Typographer’ in 1830. In Europe in the 1820s

onwards various machines were invented. In France a machine was produced in

1833 aimed at helping the blind. (It will be remembered that it was a Frenchman,

Braille, who invented a system of dots (no dashes) to help the blind.) In 1837

Ravizza's 'writing spinet' was produced, and patented in 1856. In 1839 in France

there was even a typewriter salesman.

Remington's first commercial typewriter was introduced in 1873 in America and

Mark Twain was one of the first purchasers of their machine. Scholes, from

Milwaukee, produced an experimental model in 1867. The first thousand of his

model were built by Remington (who had produced armaments) in 1873. In 1885

Tolstoy's daughter was the first European girl to use a typewriter - to be

a 'typewriter' - it is said, typing her father's letters and mss, so he was the first

European author to use a typist.

The owner of a shorthand and typewriting school had the audacity to state in

1877 that all typists should use all the fingers of both hands. A journal

condemned this assertion by saying that unless the third finger of the hand had

been previously trained to touch the keys of a piano it was not worth while

attempting to use the finger in operating the typewriter; the best operators used

only the first two fingers of each hand, and the editor doubted whether a higher

speed could be obtained by the use of more fingers. A stenographer for the

Federal Court of Salt Lake City used all his ringers, and had memorised the

keyboard. He challenged anyone to show a higher speed in typing. This challenge

was taken up by a four-finger typist. In the event the challenger won with ease.

On 25 October 1886 a paper was read at the Institute on "The Typewriter: and its

utilization by the Shorthand Writer*. Members were assured by the notice of the

meeting that 'they will be afforded a good opportunity of ascertaining and

discussing the capabilities of this important machine', known also as the 'invisible

writing machine’.

It is worth noting that before typewriters were introduced transcripts were

laboriously written in copperplate by teams of dictatees. It has been suggested

that a sheet of such written paper held 72 words, thus we had the 'folio'. One

shorthand writer has told this writer that his grandfather, at the turn of the

century, bought a typewriter and secretly kept it at home in case such conduct

would be called into question. This same source also mentions how his family sat

around the dining-room table copying transcripts. The legal profession was also

reluctant to introduce typewriters into the office, and as late as 1939 at least one

set of chambers in the Temple did not have one. Was this because in the early

part of the century at least 'typewriters' were in fact the operators?

In 1983, in America 'talking typewriters' were being sold. They were expected to

replace dictating machines.

Machine recording such as by Stenotype is considered modem and the thing for

the future. This is not so modern as the public may think. In 1827 a French

stenotype type machine was being used, employing a system of dots and dashes.

Back in 1909 a Walter Teer in America was demonstrating it across the States,

having helped start the Stenotype Company at Indianapolis. During those early

years of this century Gregg and Pitman shorthand were the dominant systems,

but Teer foresaw that the machine would take over. He claimed to write at a top

speed of 510 wpm on practice material, and 300 wpm on 'cold technical' material.

Whether or not the words were counted in syllables, as at present, is not known

to this writer, but either way Mr. Teer was a fast writer! Other machines were

patented in the years 1900,1910 and 1920. Then in 1939 in England a patent

was taken out by a Madame Camille Palanque on her machine which had 29 keys

on it, as compared with the nine keys on the Stenotype.

These machines are operated as is the piano in that by combining letters new

letters are formed (the chords of the piano), and as with the typewriter the

operation is by touch, leaving the operator to watch the speaker, which is an

advantage he has over the 'pen-pusher'. High speeds are claimed but it is still

debatable as to which method is the better.

In the 1950s a matter of major concern to the profession was the suggestion that

sound-recording be introduced into the courts. Although the Baker Committee

found that the shorthand writer 'was able to interpret the proceedings in a way

that no recording machine can', tape recorders were fitted into the courts in

London's Royal Courts of Justice, and shorthand writers are not generally

employed except in the Court of Appeal, and on writing-out cases.

An interesting story came the writer's way concerning a two-week trial held in the

High Court. Recording equipment had been set up, including microphones for the

judge and counsel and witnesses. Unfortunately, at the end of the case - not at

the end of the day - questions were found to have been recorded but none of the

answers as it was not noticed that the witness box in use (as opposed to the

other one) had not been connected. The absence of a shorthand writer would no

doubt have been noticed at some stage before the end of the case!

In the 1980s a matter of some interest to the profession is the attempted

introduction of CAT (computer-aided transcription). Although it is widely used in

the States there is a long way to go in this country before it will be considered

suitable. If ever it should be employed it will require the use of machine

shorthand, so then the manual shorthand writer will become a dying breed.

The enactment of the Contempt of Court Act in 1981 caused much concern in

reporting circles, for it was thought that allowing tape recorders into court would

at the least embarrass those taking the official note, knowing they were

competing with tape recorders placed discreetly around the court for the benefit

of the legal practitioners. It was little consolation to think they would record only

what they wanted to hear and that, therefore, the taped evidence or speech

would not be a complete rendering of what was said and so would not be in

conflict with the reporter's version. Fortunately, the matter was soon clarified in

favour of the reporters, in that permission has to be obtained before taping of

proceedings can take place. By contrast, since 1 January 1983 Californian courts

have allowed attorneys, news reporters and members of the public to take

hand-held tape recorders into court. However, these tapes cannot be used for

broadcasting, or as a substitute for the official note.

IV Notes on Notable Shorthand Writers

In our profession we can claim to have had the talented and the famous, as well

as the infamous. The following are a few of the names, some of which have lived

on through the names of firms which are still practising. The infamous are

represented by Horatio Bottomley who was orphaned at four years, having been

born in 1860, and sent to an orphanage in Birmingham from which he escaped at

about 14 years of age. After a couple of jobs, including one with a disreputable

solicitor's firm, his uncle sent him to Pitman's College to learn shorthand, which it

was thought would help him in his career. He eventually became employed by

Walpole (see below), and was later admitted to the 'exclusive' Institute of

Shorthand Writers. During his three years with Walpole he became a partner and

the firm became Walpole & Bottomley. At 24 years of age he entered journalism

and built up a chain of newspapers. His career covered journalism, company

promotion, becoming an M.P. and a shorthand writer, and committing fraud, so

that he spent some of his life in Parliament, some in the courts, and some in

prison. He died in 1933.

Henry Buckley worked at the Old Bailey in 1816, and is thought to have died in

1847. The appointment then passed to his assistant, James Drover Barnett, later

an exhibitor at the Royal Academy, and to his own son Alexander Buckley. James

Drover Barnett died in 1902; Buckley's son died in 1905. Edward Thornton and

Charles Edward Barnett wrote Mavor's system, and were still living in 1927.

John Byrom, a man of many talents, invented a system published in 1767. The

hymn, 'Christians awake, salute the Happy Morn', was his inspiration. He had

a medical degree but did not practise medicine. At one time he also took notes in

the House of Commons. In 1728 after he had been taking notes there he wrote:

'I was told I was like to have been taken into custody: but I came away free.' No

reason for this threat is known. It was said he was one of the tallest men in

England. The Wesley brothers (of Methodist fame) learned his shorthand.

George Cherer and his brother Joseph Nelson Cherer were among the writers who

formed the Society of Practising Shorthand Writers. One of those brothers is said

to have been the model for one of the Cheeryble brothers in Dickens' Nicholas

Nickleby. George Cherer died before the Institute came into being. He practised

on the Western Circuit and was concerned to help prove a certain Edmund Galley

was innocent of a charge of murder and highway robbery. He was so much

moved by Galley's plea that he called out to him 'You're a noble fellow!' Galley

ended his days having been deported to New South Wales. Being a considerate

man, George Cherer got up a monthly subscription for Alexander Frazer (q.v.)

who was in straitened circumstances. In February 1851 the Society were, at the

instigation of George Cherer, endeavouring to found a benevolent fund, but on

advice this was found to be impractical. (See also under Marten.)

Sir Edward Clarke QC published his own system in 1907 which. although adopted

by many, made less mark on the public than he himself did in the law courts.

William Cocks started practising in 1840. He was the plaintiff in an action, Cocks

v Innes, heard in 1849, in which the right to charge, inter alia, 8d per folio of 72

words was established. His younger brother Charles Brydges Cocks came into the

partnership. They both wrote the Byrom system. In 1904 Cocks sought to recover

from a solicitor payment for a transcript ordered and supplied. The defendant

argued he was not personally liable, but Channell J. held that he was. With this

precedent before them solicitors seem to be happy to pay our 'reasonable fees'.

One of a number of families of shorthand writers was the Cooke family. The

earlier John Cooke died in 1827. His son, John Henry, went into partnership but

was later admitted at Gray's Inn and was called to the Bar in 1841. A cousin,

John, was apprenticed to John Henry and then went on to cover the Oxford and

Northern Circuits. He in turn was in partnership with his son, John William, who

proved to be philanthropically disposed. He died in 1859. The second John died

about 1871; his son, John William, died in 1901. The family wrote Taylor's

system, and John Henry published his - with which he had been helped by William

Hibbit (q.v.) - in 1832 and it reached several editions down to 1866.

Charles Leopold Corfield is not really known of until 1839. In 1847 he entered

into partnership with a Frederick Williams. Corfield took an active interest in the

affairs of the then new Society of Practising Shorthand Writers, of which he was

the first auditor, and later secretary. About 1853 he left the partnership for

farming, and terminated his career in 1854 - in a horse pond!

The Counsells are said to have originated as refugees from Flanders in the

sixteenth century, settling in Somerset as weavers. William was born in 1814. In

1844 he deputised for Gurney (see below) in Ireland. From 1855 to 1862 he was

in partnership with G.B. Snell, being known as Snell & Counsell. His elder son,

William Henry, joined him as a partner but temperamentally they clashed so they

had to part company. William died in 1870. By 1869 he had taken his younger

son, Edgar, into partnership and the firm became Counsell & Son. Edgar was the

last of the writers to use quills. The HMSO discontinued the supply of quill pens to

the Royal Courts of Justice in the latter years of the nineteenth century.

The next name in this gallery is perhaps better known. Charles Dickens was

a man who championed 'the poor, the hard-done-by, and the wretched'. He

would surely have joined the Institute had it existed hen he was reporting. He

was born in 1812, and died in 1870. The period relevant to these thoughts was

around 1827 when he first of all went to work as a solicitors' clerk, as a result of

which experience he 'developed a hearty contempt' for solicitors. He bought

a copy of Gurney's 'Brachygraphy' and despite it being a 'sea of perplexity' within

a year he had mastered the subject well enough to be able to obtain work as

a shorthand reporter in the Doctors Commons, whose business was later taken

over by the PDA Division of the High Court - the 'Wills, Women and Wrecks'

Division as A. P. Herbert described it. (Further changes were made in 1971.)

When he was 18 Dickens went into journalism through an uncle who had begun

a periodical containing verbatim parliamentary reports, on which his (Dickens')

father also worked as a reporter. Charles soon established himself and was

'universally reported to be the rapidest and most accurate shorthand writer in the

Gallery'. From there he joined the staff of The Morning Chronicle, a newspaper

established some 20 years before The Times, and whose editor is said to have

created the system of notetaking by relays. ('What of the Romans?' you may

ask.) In consequence of joining The Morning Chronicle Dickens travelled the

country reporting speeches in the great Reform debate.

J. A. Dowling was a member of the Middle Temple as well as a shorthand writer.

He was one of seven sons of a Vincent Dowling, an Irish journalist of whom

Dickens spoke with special regard. Vincent Dowling was reporting for the

Observer in 1816. It has been claimed he was the first person to discern Dickens'

genius for character-sketching, and Dickens, in fact, contributed a number of

sketches to a journal which was edited by Vincent Dowling.

It was said of Alexander Fraser that he 'exercised his pen with a velocity more

rapid, if possible, than human articulation'. He had come to London from

Edinburgh. In 1794, he published Stenography, or the Art of Short Hand made

Easy and Compendious, possibly intended to have been developed into an

improvement upon Gurney's version of Mason. Around 1810 Fraser tried to get

an appointment to the Houses of Parliament but did not succeed. Objection to his

appointment was made by Gurney who claimed an exclusive privilege (see

below). Fraser was described by William Hibbit as 'a big burly unco' Scotchman'.

When he came into straitened circumstances George Cherer got up a monthly

subscription for him to which Hibbit contributed. In trying to improve on Mason's

system, Fraser devised an arrangement of double dots for combined prepositions

and articles: a single dot on the line indicated of or the, and above the line it

stood for a, an of and - some of which is familiar to Pitman writers.

Dr. John Robert Gregg who was born in Ireland, at one time wrote Pitman but

then went on to publish his cursive system, called Light Line Phonography, in

Liverpool in 1888. In that year he went off to America where he stayed to see his

shorthand used extensively until machine reporting took over.

Thomas Gurney, a schoolmaster at Luton, was the inventor of the Gurney

system, and founder of the Gurney firm. He based his on Mason's system, but it

was no improvement on the 'Brachygraphy'. according to Fraser, who also used

Mason's. Gurney published his method in 1750 and this became the prime system

for the next hundred years. Dickens used it. Until quite recently a Mr. A. C. Mill

still used it, writing at 200 wpm, and thinking nothing of working a 10-hour day.

Thomas Gurney married Martha Marsom, daughter of Thomas Marsom who was

imprisoned for his part in an unlawful assembly, and was in prison with the poet

Bunyan.

From 1738 to 1770 Thomas Gurney held the post of shorthand writer at the

Central Criminal Court (Old Bailey). His son, Joseph, followed him and he, with

William Isaac Blanchard, reported the impeachment trial of Warren Hastings over

a period of five years. William Brodie Gurney, Joseph's son, was appointed

shorthand writer to the Houses of Parliament in 1813 (a position held to this day

by the same firm). It is said that Gurney's clerks frequently worked from 11 am

to 1 or 2 the following morning while the House sat.

Thomas Gurney died in 1770. Joseph was born in 1744 and died in 1815, the

year of Waterloo (to get it into perspective).

William Brodie Gurney was born in 1777 and died in 1855. In 1830 he announced

that he would be travelling the Northern Circuit, which indicated he had accepted

work for the London Press. Good shorthand writers of that period were sought by

the Press to report trials of public interest. In those days they tended to be of two

groups; those who turned to journalism, and those who sought to establish

themselves as professional men with clienteles, modelling themselves on the

legal profession. William Brodie Gurney's brother, John, became a KC in 1876 and

eventually a Baron of the Courts of Exchequer.

William Hibbit was born in 1813. He saw the coronation procession of George IV

in 1820. He was apprenticed to Joseph A. Dowling (see above) - who 'died by his

own hand'. About 1830 he was apprenticed to J. H. Cooke and in 1838 he began

on his own account. This was one year after Victoria came to the throne. He had

earlier helped in the correction of the proofs of Cooke's edition of Taylor's system.

In 1849/50 he was in partnership with John George Hodges. About 1861 he took

into partnership his nephew, Thomas Sanders, and the firm became Hibbit &

Sanders. W. Hibbit was once President of the Institute. He died in 1905. Thomas

Sanders died in l907. They both wrote Taylor's system.

John George Hodges went on the Home Circuit and had William Hibbit as

a partner. His eldest son then became his partner (his mother being William

Counsell's sister). John George Senior died in 1875, his son in 1894. John

George's grandson, J. A. Hodges, continued the business. He was a frequent

contributor to photographic journals. He died in 1907.

One man of varied talents was Sir Ebenezer Howard, OBE, who had a social

conscience. He became founder of the town planning movement, and 'father' of

Letchworth and Welwyn Garden City, in which latter place he actually lived and

died, unlike M.P.s who represent constituencies perhaps many miles from their

homes. Sir Ebenezer was born in 1850 and died in 1928. He travelled and worked

as a reporter in the United States, then on his return to England he joined the

staff of Gurney’s. He was also an amateur, though not successful, inventor. An

invention he perfected, though never marketed, was a shorthand-typing machine.

A man of some interest was Mr. E. Gilburt Howell, whose career as a shorthand

writer was to commence in Bell Yard, Temple Bar. In 1887 his name appeared in

the roll as one of the first members of the Institute. In about 1905 he left the

firm of Hibbit & Sanders and was attached to Snell & Sons. He was a very capable

note-taker but his interest lay in the spoken word rather than the written word,

so he spent all his spare time in amateur theatricals. About four years later he

became a professional actor with the 'Blue Bird' touring company, thus travelling

to South Africa and Australia. Unfortunately the company failed in Australia and

was disbanded and so Howell found himself stranded.

He was able to obtain a post as a cook but was not successful at this and soon

afterwards he worked his way from Australia to the Fiji Islands where he

managed to get a post as shorthand writer to the Legislative Assembly and the

courts.

Nothing more was heard of Mr. Howell until 1925 when the documents in an

appeal to the Privy Council were found to include a transcript bearing his name. It

is understood he died in Sydney, Australia, in 1940.

Frederick Bond Hughes was travelling the Midland Circuit from 1830. For a period

he worked, as many of his colleagues did, as a deputy for Gurney in Parliament

as well as in reporting the Chartist meetings, at which writers often worked in

pairs so as to provide corroboration. W. Counsell and Hughes took notes together

at the trial of J. Maxwell Bryson, the latter having to admit Counsell's was the

fuller note.

Many reporters covered the trials of the Chartists, this movement having been

revived due to the economic distress which succeeded the Napoleonic Wars, and

the dislocation of society caused by the rapid industrialisation.

Alfred Richard Marten was born in Brighton in 1843. In conjunction with Thomas

Meredith he set up the firm of Marten Meredith & Co. in 1870. Around 80 years

later the present writer joined this firm. In 1980 it merged with Walsh & Sons and

became Marten Walsh Cherer Ltd. While training, it is recorded, Marten used to

work from 10 a.m. to 1 a.m. the following morning note-taking and transcribing,

which should be a salutary thought for those of us who think we are hard done by

when we start at 10 a.m. and finish at 5 p.m.! On circuit Marten could be

required to work from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. He was an accomplished musician, and

played the viola in the Stock Exchange Orchestra. He died in 1917, being the last

surviving member of the original signatories to the Memorandum of Association.

Edward Morton was born in 1801 in the West Country. He became a member of

Gray's Inn but was never called to the Bar. He was editor of a publication called

Adams' Parliamentary Handbook, and at one time published a pamphlet in which

he suggested a solution to the problem of Chancery reform which included the

suggestion that notes of the proceedings should be taken by shorthand writers.

(Was this a vested interest?) For two years he was in partnership with Francis

Neate Walsh and went the Oxford Circuit, and later the Oxford and Northern

Circuits. He added the Courts of Probate & Divorce, the Privy Council, and York

Assizes. He died in 1866.

Morton attacked Gurney's monopoly in reporting Parliament. For 15 years he had

been a deputy for Gurney. With Francis Walsh he petitioned Parliament for an

inquiry, because two-thirds of the work done was by note-takers not employed by

Gurney directly. It was stated that this monopoly lowered the character of the

profession. In June 1849 Morton petitioned the House of Lords that he be allowed

to lay before the House information on his experience to enable him to report the

proceedings. In May of that year the Society of Professional Shorthand Writers

presented a similar petition. This was turned down by the Select Committee on

Accommodation of the House as their original reference did not embrace the

subject of an official record of speeches.

It was in 1824 that Henry Richardson took into partnership George Cherer (see

above), who wrote Mavor's system, used extensively at that time, Pitman not

publishing until 1837. In 1838 his brother, Joseph Nelson Cherer, went into

partnership. George died in 1857. In 1860 Moses Bennett, an assistant, became a

partner. Joseph died in 1873. (Mavor was the Rev. William Mavor, LL.D, author of

Universal Stenography.)

George Sedgwick took an active interest in the Society of Professional Shorthand

Writers, and was for a short time its secretary.

George B. Snell was the seventh son of Richard Snell, and in turn father of five

sons. He wrote the Lewis system and taught it to at least two of his sons. He died

in 1874. During his career he was in partnership with one of the Counsells; then

with his second son, G.B. Snell, Jnr; then later with his youngest son, Thomas,

who was originally an engineer. George B. Snell, Snr. went the Northern Circuit

G.B. Snell, Jnr. maintained his connection with the Bankruptcy Court. He died in

1910, and Thomas Snell died in 1922. They were Pitman writers. The firm was

founded in 1817, with the Milner family looking after the Manchester branch, and

the Snells the London end.

James Stratford was in business in 1834. In 1852 he took Francis Neate Walsh

into partnership, until 1858 when Walsh left. Robert H. Tolcher used Taylor's

system, and started in business on his own account in 1840. He took an interest

in the 'battle of words and folios'. In 1743 Lord Hardwicke had directed that in

counting folios figures were to be counted as if written in words (as now), but to

reduce costs Lord St. Leonards, in 1852, ordered that each group of figures of

one category (i.e. pounds, shillings or pence) should be counted as one word. The

former point of view won the day. Tolcher died in 1899.

George Walpole was born in London in 1857, and died in 1928. He became

a shorthand writer and for about 18 months worked in partnership with Horatio

Bottomley who had the distinction of sitting both in and out of the dock at the Old

Bailey! Walpole edited Hansard's Debates until it ceased publication, and he was

the first reporter allowed to take notes in the House of Lords. He took the

proceedings at Royal Commissions and Departmental Committees, and claims the

record for longevity of note-taking at a trial in Carlisle: from 9.30 a.m. to 11.45

p.m. with a half-hour break for lunch and an hour's break for dinner. He also did

some newspaper reporting for the Financial Times; and he wrote a column,

London Letter, for the Singapore Free Press. He was appointed in February 1906

by the Corporation of London as the official shorthand writer at the Central

Criminal Court. In 1921 he published his own system.

Francis Neate Walsh acted as a deputy for Gurney. He was in partnership with

Morton for a short time, and later with James Stratford. He had two sons who

joined him: Henry Morton Walsh and Edward Morton Walsh. The former died in

1900, his brother in 1904.

Robert Walton was first seen as a writer in 1833 when he started on the Midland

Circuit, having gone there primarily as a representative of a London newspaper,

and hoping to establish a business of his own. This engagement went on for

a number of years. In the mid-nineteenth century writers often had a connection

with the Press. (Now we occasionally get members of the Press becoming

members of the Institute.) In about 1861 he took into partnership his son, Alfred

Grainger Walton. In 1869 Robert published a volume. Random Recollections of

the Midland Circuit, followed by a second volume in 1873. He died in the late

1870s.

Henry White was the brother of James White. Little is known of him, except that

he, again, worked mainly as a deputy for Gurney, and his career is thought to

have ended about 1860.

James White was born in 1820. He also took notes for Gurney at the Chartist

meetings and trials. He died in 1897. He was connected only with the Society.

The first knowledge of Frederick Williams is as from 1839. Soon after termination

of a partnership with Charles L. Corfield he took Joseph Hurst, Snr. into

partnership. By 1854 William Archer Corfield, a brother of Charles, was his

partner. It is thought that Williams died in about 1856. From 1870 Joseph Hurst

was in partnership. Corfield dropped out through ill-health' so the firm became

Hurst & Hurst. Corfield then entered into partnership with Charles Hersee who

had originally been with Hurst, Corfield & Hurst, so originating the firm of Corfield

& Hersee. Joseph Hurst, Snr. died in 1885. His son went to the Bar in 1887, and

the firm became Barnett & Barrett, consisting of Edward Thornton Barnett and

William George Barrett, an ex-assistant of Hurst & Hurst. William George Barrett

died in 1923, then in 1924 Edward Thornton Barnett joined Henry Lenton as

Barnett, Lenton & Co. (now practising from Chancery Lane). W.A. Corfield, Snr.

died about 1875; W.A. Corfield, Jnr. died in 1911; and Hersee died in 1917. The

Hursts, Hersee, and W. G. Barrett wrote Taylor's system, and the Corfields wrote

Lewis's.

Another note-taker who wrote his memoirs was Lloyd Woodland, Jnr., who wrote

of the Winchester court under the title Assize Pageant. His father had had

a personal appointment to the Winchester Assize and Quarter Sessions back in

1908, at which he was assisted by H. Sanders. More latterly Sellers and

Woodland worked together at Hampshire Assizes. Woodland, Jnr. left shorthand

writing for the local authority.

V Comments by Judges

It is interesting to note, looking through judgments pronounced over the last

century, the comments of judges on the shorthand writer and his craft. The

following is a small selection.

In 1862 Sir John Romilly, Master of the Rolls, suggested, in the case of Clarkv

(Malpas (31 Beav. 554, 559) 'the propriety of using the shorthand writer's note,

in consequence of the much greater certainty and accuracy acquired thereby ...

than by the note taken by the judge'.

In 1871 in Tichborne v Lushington (May 12, 1871; M. Levy, 'Shorthand Notes’

(1886), 37, 38, 39) Bovill, Lord Chief Justice, said:

Probably this would be much more accurate than the note which I could take. If

you think so, the examination may pass on much more rapidly, because they

need not wait for me to take a note of every piece of evidence ... The gentleman

who is taking the notes could always refer to the exact question and

answer...I must give the shorthand writer authority to stop the proceedings if you

are going a little too rapidly for him.

In the case of Earl de la Warr v Miles (9 Nov. 1881; M. Levy, ubi supra, 69), the

distinguished if opinionated Sir George Jessel, M.R. inveighed against the idea

(pp.72-3):

The shorthand writer... is not so competent to take a proper note as the Judge

and counsel. As a general rule he has not a sufficient knowledge of the case to

know the exact bearings of the answers, especially in technical or scientific cases

...he very often changes during the course of the trial, for we all know that

a shorthand writer cannot go on all day; he must change from time to time, and

therefore he may come in in the middle of a case without knowing anything about

it... if a witness's answer is not understood by him he cannot call upon the

witness to repeat the answer as a Judge can, if he is in doubt, so as to make his

note perfect. Therefore it is impossible to say that, as a rule, a shorthand writer's

note is the best record or the most reliable record of the evidence.

On the supposed problems raised by technical terms another view was taken by

the court in the case of Badische Anilin Fabrik v Levinstein ((1883) 24 Ch. D. 156,

at 176):

The case was one of extreme technicality, and it would be almost a necessity that

a shorthand note should be taken of the whole of the evidence. Mr. Justice

Pearson said he considered that, in cases of this nature, it was most important

that the whole of the evidence should be taken by a shorthand writer. The case

occupied the court for ten days. The witnesses were some of the principal

authorities upon chemistry.

A daily transcript was provided. The report in the London Times added the

following:

The shorthand notes have been taken with great correctness; but loud complaints

are made by the reporters of the extreme inconvenience of the present position

of their desk in the new court, which is so much below the level of the judge's

seat and the witness box that it is with the utmost difficulty that they are able to

hear the judge or witness.

There are further references to this familiar difficulty earlier in this article!

In the celebrated Canadian appeal of Louis Riel to the Judicial Committee of the

Privy Council in London ((1885) 10 App. Cas 675) the original magistrate had

directed a shorthand writer to take down the evidence, and as a result the

magistrate himself could not read the characters. It was argued that the

magistrate had not therefore had a note made of the evidence. Lord Halsbury,

Lord Chancellor, giving the judgment, said that a shorthand note was a form of

writing and the legal requirements had been met (p.679).

In the recent case of R. v Dowling in the Court of Appeal (The Times, 22 June,

1988) it was pointed out that a judge should not alter a sentence otherwise than

in open court as 'only thus would a shorthand note be recorded and available'. In