Using the Psychological Commitment

to Team (PCT) Scale to Segment Sport

Consumers Based on Loyalty

Daniel F. Mahony, University of Louisville

Robert Madrigal and Dennis Hovk'ard, University of Oregon

Abstract

The purpose of this study was to de-

velop a psychological commitment

to team (PCT) scale to be used in

segmenting sport consumers based

on loyalty. Previous research on the

loyalty construct suggested the im-

portance of using both behavioral

and attitudinal measures when at-

tempting to assess the loyalty of

consumers (Backman & Crompton,

1991a;

Day, 1969). Although mea-

sures of behavioral loyalty are

read-

ily available in team sports

(e.g.,

at-

tendance, television viewing), no

appropriate measure of attitudinal

loyalty was available prior to the

- current study. A number of statisti-

cal procedures and four separate

data collections were used to assess

' the strength of the PCT scale. The

PCT scale provides sport marketers

with a reliable and valid measure-

ment tool for differentiating con-

sumers into discrete segments based

on the strength of their overall loy-

Daniel

F.

Mahony

is an

assistant

professor

vv/f/? the Department of

HPES

at the University of

Louisville.

Robert Madrigal

is an

assistant

professor with the Department of

Marketing in the Lundquist College

of

Business

at the University of

Oregon.

Dennis

Howard

is

a

professor

with the Department of Marketing

in the Lundquist

College

of

Busi-

ness

at the University of

Oregon.

alty. Alternative strategies for

strengthening fan allegiance for

each of the different loyalty seg-

ments are provided.

***

"Marriages come and go. So

do jobs, hometowns, friend-

ships.

But a guy's attachment

to a sports team? There's a

bond that holds the heart."

The preceding statement on fans'

obsession with sports teams ap-

peared recently as the lead sen-

tence in a feature article in USA

Today,

the United States' largest

daily newspaper (Eisler, 1997). The

quote captures the fanaticism or in-

tense partisanship that Guttmann

taled $8.8 billion, an increase of

126%

over the $3.9 billion spent in

1990 (National Sporting Goods As-

sociation,

1996). Although fans'

time and monetary investments in

sports seem to have grown expo-

nentially in recent

years,

it is impor-

tant to recognize that not all those

who watch or attend sporting

events are fans committed to the

teams they view. Zillman and

Paulus (1993) characterized

specta-

tors as

individuals who watch a

game but then forget about the ex-

perience once it is over, whereas

Sloan (1989) said a fan is one who

watches as an enthusiastic devotee.

The Concept of Fan Loyalty

Although the notion of loyalty to

team extends back to antiquity (Lee,

Although fans' time and monetary investments in sports seem

to have grown exponentially in recent years, it is important to

recognize that not all those who watch or attend sporting

events are fans committed to the teams they view.

(1986) uses to define fans as "emo-

tionally committed consumers of

sporting events" (p. 6). The atten-

tion given to sport by hard-core fans

and other spectators is well docu-

mented.

Americans buy almost 200

million tickets to attend professional

and collegiate sporting events each

year (U.S. Bureau of

Census,

1993),

spending about $5 billion annually

for admission (Bureau of Economic

Analysis, 1996). In 1996, the retail

sales of products bearing the trade-

mark or logo of teams in the four

major professional sports leagues in

the United States and Canada to-

1983), very little is known about the

social-psychological factors that

produce strong emotional attach-

ment to sports teams or organiza-

tions.

Previous research outside the

sport-fan literature has shown that

individuals who are emotionally in-

volved devotees to a particular

product or service are far more

likely to repurchase that product or

service and to evaluate the brand or

experience more positively

(e.g.,

Havitz & Howard, 1995). Smith,

Patterson,

Williams, and Hogg

(1981) found the same relationship

extended to sport

fans.

Although not

m

O

m

Z

o

Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 15

addressing the concept of loyalty

directly, their study of avid sport

fans found that "deeply committed

fans"

displayed a much greater

propensity to watch and attend

sporting events featuring their fa-

vorite teams. More recently, Wake-

field and Sloan (1995) concluded

that "team loyalty," defined as en-

during allegiance to a particular

team,

was the most important factor

in determining spectators' desire to

attend live sporting events.

Although there are many behav-

iors that may be an expression of

fan loyalty

(e.g.,

television viewing,

radio listening, team merchandise

purchases), prior research has relied

heavily on attendance data to mea-

sure fan loyalty to sports teams.

Total attendance

(e.g.,

Baade &

Tiehan,

1990), increases in ticket

sales

(e.g.,

Howard & Crompton,

1995), and the extent of repeat at-

tendance

(e.g.,

Mullin, Hardy, &

Sutton,

1993) have been used as

behavioral indicators of consumers'

loyalty to a sports team or organiza-

tion.

Mullin and his associates

demonstrated the potency of repeat

patronage, confirming the applica-

tion of the "80-20 principle" (Evans

& Berman, 1994) to sports teams. In

their analysis of season attendance

at Pittsburgh Pirates games, Mullin

et al. found that 80% of the in-

crease in ticket sales from one sea-

son to another was produced by

20%

of the existing attendees' buy-

ing more tickets. Although repeat

attendance may be the most evident

manifestation of a person's attach-

ment to a team, this strictly behav-

ioral indicator ignores the underly-

ing psychological processes

explaining why some people attend

more games over time.

In fact, research has shown atten-

dance alone is a poor measure of

loyalty. Murrell and Dietz (1992)

found individuals' support for a par-

ticular team may be strong regard-

less of actual attendance. Backman

and Crompton (1991a) identified

several factors explaining why

strictly behavioral or "observable"

measures like attendance are inade-

quate indicators of loyalty. They

contend that "behavioral measures

do not discriminate between pur-

chasing based on habit or lack of

convenient opportunities" (p. 206).

For example, an NFL fan in

Nashville, Tennessee, may attend

Tennessee Titans games because

there are no other professional foot-

ball options in the area, and he or

she may not necessarily be a com-

mitted fan of the Titans. Therefore,

"true"

loyalty exists only when the

consumer regularly purchases the

product or service and also displays

a strong, positive attitude toward a

specific brand (Day, 1969).

Loyalty as a

Two-Dimensional Construct

The multidimensional nature of loy-

alty has long been of interest to

brand loyalty researchers. In order

to provide a focus for this research,

Olson and Jacoby (1971) developed

a six-point definition of brand loy-

alty, which is now widely cited.

Their definition, later restated

slightly by Jacoby and Kyner (1973),

states that brand loyalty is "(1) a bi-

ased

(i.e.,

nonrandom), (2) behav-

ioral response

(i.e.,

purchase) (3) ex-

pressed over time (4) by some

decision making unit (5) with re-

spect to one or more alternative

brands (6) as a function of psycho-

logical (decision making, evaluate)

processes" (p. 2). Although Jacoby

and Kyner (1973) focused on testing

all six of the elements, most of the

Although repeat attendance may be the most evident manifes-

tation of a person's attachment to a team^ this strictly behav-

ioral indicator ignores the underlying psychological processes

explaining why some people attend more games over time.

In fact, research has shown attendance alone is a poor

measure of loyalty.

loyalty research has focused primar-

ily on two main dimensions, behav-

ioral and attitudinal

(e.g.,

Backman

& Crompton,

1991

a,

1991

b; Jacoby

& Chestnut, 1978). Although Day

(1969) was the first to propose a

two-dimensional conceptualization

of loyalty integrating both behav-

ioral and attitudinal components,

later research provided empirical

evidence that consumer loyalty was

in fact composed of these two sepa-

rate but related elements

(e.g.,

Backman & Crompton, 1991a,

1991b; Olson & Jacoby, 1971).

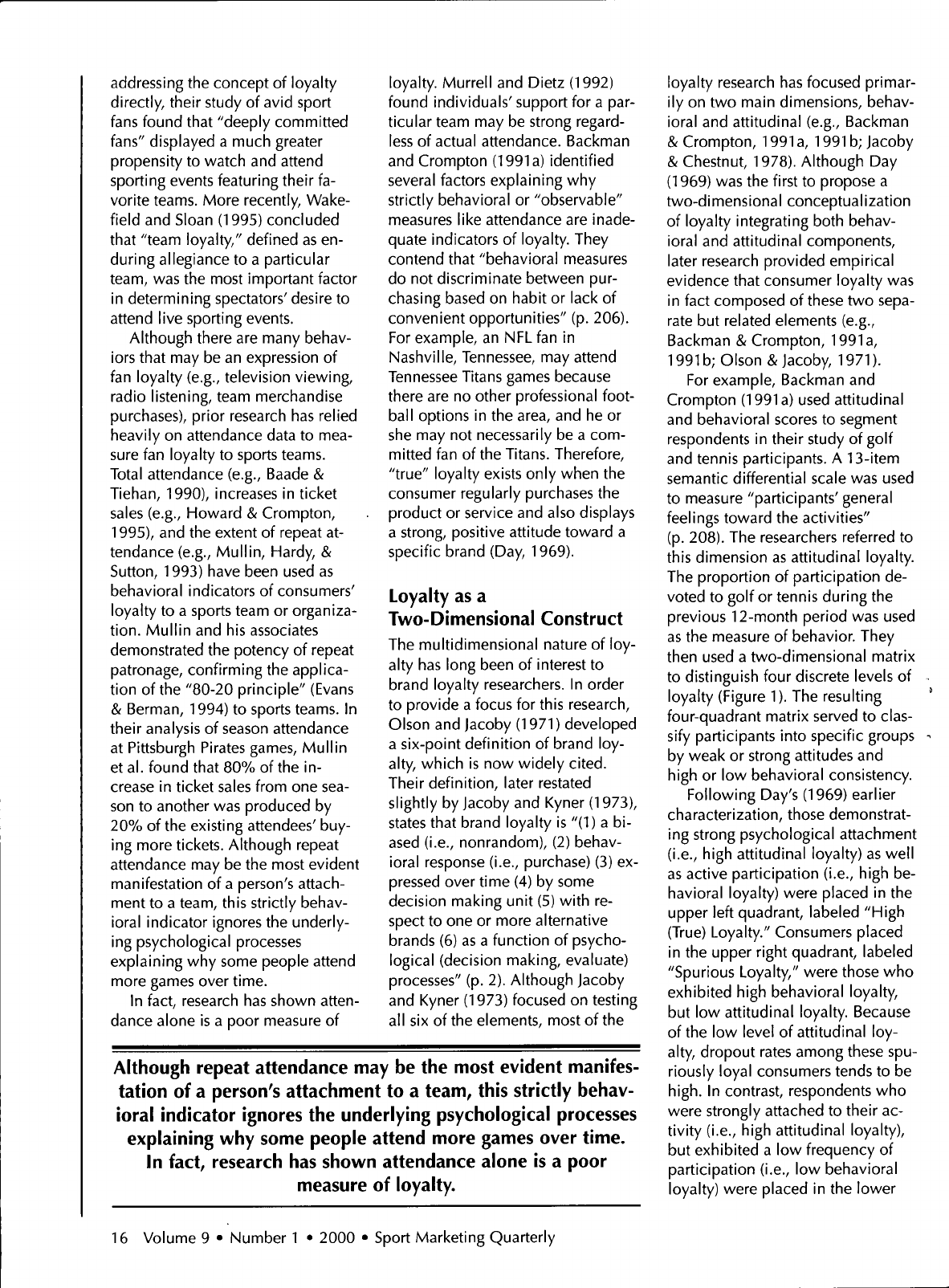

For example, Backman and

Crompton (1991a) used attitudinal

and behavioral scores to segment

respondents in their study of golf

and tennis participants. A 13-item

semantic differential scale was used

to measure "participants' general

feelings toward the activities"

(p.

208). The researchers referred to

this dimension as attitudinal loyalty.

The proportion of participation de-

voted to golf or tennis during the

previous 12-month period was used

as the measure of behavior. They

then used a two-dimensional matrix

to distinguish four discrete levels of

loyalty (Figure 1). The resulting '

four-quadrant matrix served to clas-

sify participants into specific groups ^

by weak or strong attitudes and

high or low behavioral consistency.

Following Day's (1969) earlier

characterization, those demonstrat-

ing strong psychological attachment

(i.e.,

high attitudinal loyalty) as well

as active participation

(i.e.,

high be-

havioral loyalty) were placed in the

upper left quadrant, labeled "High

(True) Loyalty." Consumers placed

in the upper right quadrant, labeled

"Spurious Loyalty," were those who

exhibited high behavioral loyalty,

but low attitudinal loyalty. Because

of the low level of attitudinal loy-

alty, dropout rates among these spu-

riously loyal consumers tends to be

high.

In contrast, respondents who

were strongly attached to their ac-

tivity

(i.e.,

high attitudinal loyalty),

but exhibited a low frequency of

participation

(i.e.,

low behavioral

loyalty) were placed in the lower

16 Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Psychological Commitment

Strong Weak

High

Behavioral

Consistency

(Attendance

Frequency)

Low

High (True)

Loyalty

Latent

Loyalty

Spurious

Loyalty

Low (Non)

Loyalty

Figure 1. Loyalty Model

left quadrant, labeled "Latent Loy-

alty." Latently loyal consumers often

express a strong desire to partici-

pate,

but may lack the means

(e.g.,

time,

money, equipment) to engage

in the activity on a regular, ongoing

basis.

Finally, those in the lower

right quadrant, or "Low Loyalty"

segment, were respondents who ex-

hibited low levels of both behav-

ioral and attitudinal loyalty.

Backman and Crompton (1991b)

advanced the understanding of loy-

alty in a sport and leisure context in

two important ways. First, their

two-dimensional approach

reaf-

firmed and extended Day's (1969)

claim that any measure of a per-

son's commitment to a brand or, in

the case of Backman and Cromp-

ton's work, a sport "activity" must

take into account the individual's

disposition toward that activity

(i.e.,

attitude) as well as the fre-

quency of his or her participation

(i.e.,

behavior). Second, their

iden-

tification of four discrete levels of

loyalty provided important insights

into the complexity of the con-

struct. They demonstrated that the

traditional all-or-none portrayal of

loyalty as a simple dichotomy be-

tween loyal and nonloyal con-

sumers was far too narrow. For ex-

ample,

the ability to measure con-

sumers' strength of attachment to a

particular sport product or service

in order to separate the highly loyal

from the spuriously loyal is crucial

to distinguishing genuine loyalty

from habitual purchase behavior.

Commitment as

Attitudinal Loyalty

Although Backman and Crompton

(1991 a)

demonstrated the impor-

tance of linking attitudes with be-

haviors in measuring loyalty, the ap-

proach they used in

operationalizing the attitude com-

ponent, which they termed "psy-

chological attachment," was very

for measuring the attitude

bias component of loyalty.

These researchers devel-

oped a scale for measuring

loyalty toward specific

travel-service providers,

such as airlines and hotels.

They used the construct of

commitment as the founda-

tion for explaining the psy-

chological processes un-

derlying and leading to

consumer loyalty. A num-

ber of researchers have ar-

gued that psychological

commitment best describes

the attitude component of

loyalty. Day (1969) con-

tended true loyalty exists

only when there is "com-

mitment to a brand or

product." Jacoby and

Chestnut (1978) further

elaborated the construct's

connection to loyalty, stating that

"as a result of this evaluative

process, the individual develops a

degree of commitment to the brand

in question; he is 'loyal.' The con-

cept of commitment provides an es-

sential basis for distinguishing be-

tween brand loyalty and other forms

of repeat purchasing behavior

(p.

84).

According to Crosby and Taylor

(1984), people who are high in psy-

chological commitment "resist

changing their preference in re-

sponse to conflicting information or

experience" (p. 414). Drawing

heavily from the work of Crosby

and Taylor, Pritchard et al. (1999)

operationalized psychological com-

The purpose of this study is to extend Pritchard et al/s

(1999) work to estahlish a scale for assessing the strength

of an individual's commitment to sport teams. It is expected

that fans who demonstrate loyalty toward a sports team

possess an attitude bias that is both resistant to change

and persistent over time.

limited.

Pritchard, Havitz, and

Howard (1999) were the first to pro-

vide both a theoretically grounded

and psychometrically sound basis

mitment as the tendency to resist

changing one's preference based on

the desire to maintain cognitive

consistency. The desire for consis-

Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 17

tency between an individual's be-

liefs and feelings toward an object

produces a stable behavioral inten-

tion toward that object (Rosenberg,

1965). Support for Crosby and Tay-

lor's interpretation of commitment

based on resistance to change is

found in Kiesler's (1971) earlier

work on commitment. Kiesler and

associates established in several ex-

periments that the "effect of com-

mitment is to make an act less

changeable" (Kiesler & Mathog,

1971;

Kiesler & Sakamura, 1966,

p. 349). Moreover, recent research

suggests "that loyal consumers—

those who have a strong commit-

ment to a service or brand—show

strong resistance to counter persua-

sion attempts" (Schiffman & Kanuk,

1997,

p. 223).

Proceeding,

then,

on the belief

that psychological commitment was

a strong barometer of preference sta-

bility, Pritchard et

al.

(1999) devel-

oped a scale that measured the

atti-

tude component of loyalty on the

basis of how committed people were

toward a specific travel service. Fol-

lowing a rigorous scale construction

procedure (Churchill, 1979; Dawis,

1987), the researchers developed a

13-item scale that demonstrated

strong psychometric qualities. Using

samples across three travel-service

subsets (destination golf

resorts,

air-

lines,

hotels), Pritchard and his asso-

ciates produced an instrument dis-

playing consistently high reliability

as well as discriminant and conver-

gent validity.

Creating a Commitment

to Team Scale

The purpose of this study is to ex-

tend Pritchard et al.'s (1999) work

to establish a scale for assessing the

strength of an individual's commit-

ment to sport teams. It is expected

that fans who demonstrate loyalty

toward a sports team possess an at-

titude bias that is both resistant to

change and persistent over time. In

addition,

it is expected that strong

and weak attitudes, or levels of per-

sonal commitment, toward a team

would be effective guides to behav-

ior (Fazio, 1995; Petty, Haugtvedt, &

Smith,

1995). Those individuals

scoring high on the personal com-

mitment scale would accurately rep-

resent those fans truly devoted to a

particular

team.

Conversely, those

scoring low would be classified, at

best, as spuriously loyal, with a sub-

stantial number having little or no

emotional attachment to the team.

Determining the strength of an

indi-

vidual's attitude or commitment,

therefore, would allow for meaning-

ful differentiation between "fair-

weather" and "deeply committed"

fans (Smith

etal.,

1981).

Scale Development

The Psychological Commitment to

Team (PCT) scale (see Table 1) was

developed using multiple steps and

four phases of data collection. In-

strument development relied heav-

ily on the work of Pritchard et al.

(1999) and the suggestions of

Churchill (1979) on scale develop-

ment

(e.g.,

generating items, purify-

ing the measure, assessing reliabil-

ity and validity). Specifically, the

following steps were taken in the

current study: (a) items were gener-

ated;

(b) items were pretested;

(c) scale was tested with three sepa-

rate samples in three different team

sport settings

(i.e.,

professional foot-

ball,

college football, professional

basketball) to establish internal

consistency and reliability; and

(d) scale was tested with two sam-

ples (one from the University of Ok-

lahoma and one from The Ohio State

University) to determine if it had

construct and predictive validity.

Generating Items

Based on the findings of Crosby and

Taylor (1983) and the results of re-

cent attitude strength studies

(Haugtvedt & Petty, 1992;

Haugtvedt & Wegener, 1994), resis-

tance to change was believed to be

a critical factor underlying commit-

ment. Therefore, items were gener-

ated that emphasized the impor-

tance of resistance to change. In

particular, the authors attempted to

measure whether fans would re-

main committed to the team when

something occurred that might

change their commitment

(i.e.,

poor

team performance, loss of good

players, change in the coach).

A couple of items from the

origi-

nal Pritchard et al. (1999) PCI scale

were determined to be easily adapt-

able to a sports context and were

included in the item

pool.

As sug-

gested by Churchill (1979),

addi-

tional items based on a review of

the literature on sport fans were

then generated by the authors.

Churchill's suggestion that items be

worded both positively and nega-

tively was also followed. The Psy-

chological Commitment to Team

(PCT) scale used a

7-point

Likert

scale ranging from strongly

disagree

to strongly

agree.

Positively worded

items were scored from

1

for

strongly disagree to 7 for strongly

agree,

whereas negatively worded

items were scored from 7 for

strongly disagree to

1

for strongly

agree.

Therefore, a higher score al-

ways represented greater psycho-

logical commitment to the team.

The 15 total items generated were

then sent to a panel of judges to de-

termine the appropriateness of each

item with respect to clarity and face

validity. The panel, which included

experts in research related to sport

consumer behavior, provided unan-

imous support for the inclusion of

all 15 items.

Pretesting Items

A convenience sample (N=100) was

then used to examine the scale for

internal consistency. Using an initial

sample to purify the measure is also

a suggestion made by Churchill

(1979). All surveys collected were

usable. The respondents were in-

coming freshmen at The Ohio State

University who were recruited from

the 1994 summer orientation pro-

gram.

Each was asked to answer the

questions with regard to his or her

favorite National Football League

(NFL) team. Professional football

was selected because of its popular-

ity in the United States and because

of the general awareness of NFL

teams. A

USA Today/Gallup

Poll

found that professional football

18 Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

Table 1. Item-to-Total Correlations and Alpha Coefficients If That Item Were Deleted for the

PCT Scale

Item-to-Total Correlations

Alpha If Deleted

Item

Sample 2 Sample 3

(N=157)

Sample 4

(N=76)

Sample 2 Sample 3

Sample 4

1.

1

might rethink my allegiance to my favorite team if this team consistently performs poorly.

.595 .481 .739 .87 .88 .94

2.

I would watch a game featuring my favorite National Football League (NFL) team regardless of which team

they are playing.

.255 .353 .679 .88 .88 .94

3. I would rethink my allegiance to my favorite team if management traded away its best players.

.371 .473 .773 .88 .88 .94

4.

Being a fan of my favorite NFL team is important to me.

.635 .550 .760 .87 .87 .94

5. Nothing could change my allegiance to my favorite NFL team.

.673 .684 .723 .87 .87 .94

6. I am a committed fan of my favorite NFL team.

.733 .713 .808 .86 .86 .94

7. It would not affect my loyalty to my favorite NFL team if management hired a head coach that

1

disliked very

much.

.513 .497 .653 .88 .88 .94

8. I could easily be persuaded to change my favorite NFL team preference.

.690 .564 .791 .87 .87 .94

9. I have been a fan of my favorite team since I began watching professional football.

.360 .516 .569 .88 .88 .94

10.

1

could never switch my loyalty from my favorite NFL team even if my close friends were fans of another team.

.690 .728 .814 .87 .86 .94

11.

It would be unlikely for me to change my allegiance from my current favorite NFL team to another.

.765 .754 .781 .87 .86 .94

12.

It would be difficult to change my beliefs about my favorite NFL team.

.813 .760 .714 .86 .86 .94

13.

You can tell a lot about a person by their willingness to stick with a team that is not performing

well.

.354 .300 .465 .88 .88 .94

14.

My commitment to my favorite NFL team would decrease if they were performing poorly and there appeared

little chance their performance would change.

.426 .346 .739 .88 .88 .94

ranked first in popularity among the

four major professional sports in the

United States (as cited in Mihoces,

1995). Examination of the item-to-

total correlations found one item ("It

is normal for a person to change their

allegiance to a local team after relo-

cating") had a low negative correla-

tion with the total

(t^.O8).

Because

the item had such a low correlation

and did not ask about the fan's per-

sonal relationship with his or her fa-

vorite

team,

the item was eliminated

from the scale, resulting in the 14-

item PCT scale that was further tested

with the three remaining samples.

Establishing Internal

Consistency and Reliability

A second convenience sample

{N=^

51) was recruited from under-

graduate classes at the University of

Oklahoma. The original sample size

was 153, but 2 respondents were

eliminated because they indicated

they had no favorite team. The final

sample (N=151) included 89 men

(58.9%) and 62 women (41.1%)

with a mean age of 23.45 (approxi-

mately 23 years 6 months old). Re-

spondents were again asked to an-

swer the questions with regard to

their favorite NFL team. As per

Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 19

Churchill's (1979) recommendation,

Cronbach's (1951) coefficient alpha

was used initially to examine the

measure's internal consistency to

help establish reliability. Cronbach's

coefficient alpha estimate for the 14-

item PCT scale was .88. This

esti-

mate was greater than the .70

mini-

mum that has been suggested by

Nunnally and Bernstein (1994). Ex-

amination of the item-to-total corre-

lations (see Table 1) found that only

item number 2 had an item-to-total

correlation of less than .30 (r= .25).

This item was not eliminated from

the scale for several reasons:

(a) eliminating this item would not

have changed the coefficient alpha

estimate; (b) the item-to-total corre-

lation was very close to the .30

mark being used in this study; (c) the

item had an item-to-total correlation

well above .30 during the pretesting

of the scale (r = .54); and (d) the

item was believed to be important in

measuring psychological commit-

ment to team (PCT) because of the

results of prior research and the

studies related to the domain of this

item-to-total correlation for item 2

was .353. Therefore, the authors

believe the decision to keep this

item was appropriate.

The fourth convenience sample

(/V=76)

was collected from students

at The Ohio State University.

Self-

identified Ohio State fans were

asked to fill out the scale with re-

gard to the OSU football team. The

only item that had to be adjusted

group.

One common method for de-

termining the validity of

a

scale is to

distribute the scale to a group that

should score high on the scale

(Churchill,

1979). If the group does

in fact indicate a high score, this

would be further evidence to support

the scale's construct validity. When

examining the fourth convenience

sample, fans who indicated they had

a very strong interest in Ohio State

Overall,

the PCT scale demonstrated strong predictive

validity, and the analysis provided evidence of its construct

validity. Therefore, the scale appears to be useful with both

college and professional teams.

somewhat was item number 3. The

item,

which was worded

"1

would

rethink my allegiance to my favorite

team if management traded away its

best players" when examining pro-

fessional sport teams, was changed

to "I would rethink my allegiance to

the Ohio State football team if their

best players left the team

(i.e.,

trans-

football {N-43; a score of 6 or 7 on

a one-item measure with 1=Minimal

Interest to 7=Strong Interest), the PCT

score was very high (M=88.09,

S.D.=8.76). This is much higher than

the average score on the PCT scale

with the professional football sample

(A^=70.12) and the professional bas-

ketball sample (A^=62.60). In

addi-

The Psychological Commitment to Team (PCT) scale provides researchers with a reliable and

valid tool for measuring attitude loyalty, or the strength of fans' commitment to a particular

sports team. Previous research has shown that capturing the dispositional nature of attach-

ment is crucial to establishing true loyalty.

construct (Crosby & Taylor, 1983).

A third convenience sample

{M-^

57)

was recruited from a num-

ber of graduate and undergraduate

classes at the University of

Louisville. The sample included

113 men and 44 women with a

mean age of

23.01

years. This time

respondents were asked to answer

the questions with respect to their

favorite National Basketball

Association team. Cronbach's

coef-

ficient alpha was used once again

to examine the scale's internal con-

sistency. Cronbach's alpha estimate

for the 14-item scale was again .88,

establishing the reliability of the

scale items. The item-to-total corre-

lations (see Table 1) were .30 or

better for all items. In particular, the

fer, graduate, etc.)." All question-

naires were completed, and they

were all usable. Cronbach's coeffi-

cient alpha was used once again to

examine the scale's internal consis-

tency to help further establish relia-

bility. Cronbach's alpha estimate for

the 14-item scale was .94, again ex-

ceeding the minimum threshold of

.70 suggested by Nunnally and

Bernstein (1994). The item-to-total

correlations, shown in Table 1,

were better than .45 for all items.

Establishing Construct

and Predictive Validity

The authors used a number of meth-

ods to establish construct and pre-

dictive validity. First, the authors ex-

amined the PCT scale with a known

tion,

a one-way ANOVA (with inter-

est in OSU football as the

independent variable and score on

the PCT as the dependent variable)

showed that fans who indicated a

strong interest in OSU football (6 or

7) scored significantly higher on the

PCT scale than did fans who had less

interest in OSU football (N=33; less

than 6 on a scale of

1

to 7),

F(1,

74)

= 104.33, p <

.001.

Therefore, the

examination of the known group

provided support for the construct

validity of the PCT scale.

Second,

another method for de-

termining if an attitude scale is

valid is to examine if scores derived

from the scale can predict related

behaviors. In fact, a recent meta-

analysis by Kraus (1995) found that

20 Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

attitudes have been very useful in

predicting future behavior in a

vari-

ety of settings. Because a strong re-

lationship is expected between

atti-

tudinal loyalty and behavioral

loyalty, a series of analyses were

used to determine if the Psycholog-

ical Commitment to Team (PCT)

scale was significantly related to

various measures of behavioral loy-

alty. Using the second convenience

sample, the current study examined

the relationship between score on

the PCT scale and (a) the duration

of one's commitment to a team,

(b) the frequency with which, ac-

cording to their own report, the re-

spondents generally watched their

to Team scale again demonstrated

good predictive validity when used

to analyze Ohio State football fans

in the fourth convenience sample.

The relationship between score on

the PCT scale and three behavioral

measures of fan loyalty was exam-

ined.

First, a regression analysis was

used to determine whether the re-

spondents' scores on the PCT scale

could be used to predict the num-

ber of Ohio State football games at-

tended during the last season. The

results indicated that psychological

commitment to the Ohio State foot-

ball team did make a significant

contribution to the prediction of the

number of games attended.

p <

.001.

Analysis of the frequen-

cies indicated those who scored

higher on the PCT scale were more

likely to make every effort to watch

or listen to the team.

Overall,

the PCT scale demon-

strated strong predictive validity,

and the analysis provided evidence

of its construct validity. Therefore,

the scale appears to be useful with

both college and professional

teams.

Conclusion and Implications

The Psychological Commitment to

Team (PCT) scale provides re-

searchers with a reliable and valid

tool for measuring attitude loyalty.

Knowing what percentage of a team's existing fan base falls into

high,

spurious, latent, or low

loyalty categories provides a starting point for developing customized programs that account

for varying levels of attachment held by fans. The varying attitude-behavior combinations rep-

resented in each cell in Figure 1 suggest that different approaches to changing or maintaining

current levels of loyalty are required for each segment.

favorite team on television, and

(c) the percentage of games featur-

ing their favorite team that the re-

spondents actually watched during

the NFL regular season.

The correlations between the

Psychological Commitment to Team

(PCT) scale and all three behavioral

loyalty measures were examined to

determine whether the scale

demonstrated effective predictive

validity. High correlations with

these behavioral loyalty measures

would indicate that the measure is

appropriate for assessing attitudinal

loyalty. First, there was a significant

positive correlation between the

PCT scale and the number of years

as a fan of the favorite

team,

r= .426,

p <

.001.

Second, there was a sig-

nificant positive correlation be-

tween the PCT scale and how often

the respondents generally watched

their favorite team, r= .584,

p <

.001.

Third, there was a signifi-

cant positive correlation between

the PCT scale and the percentage of

the favorite-team games respon-

dents actually watched during the

NFL season, r = .563, p < .001.

The Psychological Commitment

(/?2 = .273, p< .001). Second, a

chi-square analysis examined

whether scores on the PCT scale (a

median split was used on PCT

score) could predict whether stu-

dents had purchased Ohio State

football tickets during the prior sea-

son.

The results of the chi-square

analysis indicated there was a sig-

nificant relationship between psy-

chological commitment to the OSU

football team and the purchase of

season tickets, x^ {df-^) - 8.85,

p < .003. Analysis of the frequen-

cies indicated that those who

scored higher on the PCT scale

were more likely to buy season tick-

ets.

Third, another chi-square analy-

sis examined whether "score" on

the PCT scale (a median split was

again used on PCT score) could

predict whether the student "makes

every effort to watch or listen" to

Ohio State football games he or she

does not attend. The results of the

chi-square analysis indicated there

was a significant relationship be-

tween psychological commitment

to the OSU football team and mak-

ing an effort to watch or listen to

the team, xMc//'=1) = 14.77,

or the strength of fans' commitment

to a particular sports team. Previous

research has shown that capturing

the dispositional nature of attach-

ment is crucial to establishing true

loyalty (Day, 1969; Dick & Basu,

1994). Research by Howard and

Thompson (1984) has shown that

customers' level of loyalty to a par-

ticular brand or service mediates

their responsiveness to accompany-

With spuriously loyal fans,

the strategy would be to

increase the psychological

commitment to the team

they are already supporting

behaviorally. Again,

increased attitudinal loyalty

among this segment is

extremely important because

these are generally the fans

who will stop supporting the

team when something goes

wrong

(e.g.,

team perfor-

mance decreases; a popular

player is traded).

Volume 9 • Number! • 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 21

ing information and their intentions

to repurchase that good or service.

The stronger the attitude typically

the greater the likelihood of congru-

ent behavior. Not surprisingly,

then,

the more positively disposed

indi-

viduals are toward a particular ob-

ject, the more likely they are to at-

tend to advertising messages

relevant to that object, share

posi-

tive affirmations

(e.g.,

word of

mouth) about the object, and

ulti-

mately, purchase the product.

The initial tests conducted in this

study demonstrated the score de-

rived from the PCT scale by itself

can be very useful in predicting at-

tendance at sporting events and

television viewing behavior. The

scale's capabilities for predicting

loyal behavior in the future, how-

with behavior

(e.g.,

frequency of re-

peat purchase) provides a basis for

differentiating customers into mean-

ingful loyalty segments. The easy-

to-administer PCT scale provides

sport marketers with a tool for as-

sessing the extent to which their ex-

isting fan base falls into deeply

committed or fair-weather fan cate-

gories. Knowing what percentage of

a team's existing fan base falls into

high,

spurious, latent, or low loyalty

categories provides the basis for de-

veloping a marketing program that

optimizes the potential for strength-

ening fans' attachment to the team.

Knowing what percentage of a

team's existing fan base falls into

high,

spurious, latent, or low loyalty

categories provides a starting point

for developing customized pro-

Low-loyalty consumers are the most challenging segment.

These infrequent or nonattending patrons hold^ at best, an

ambivalent attitude toward the sports team. Converting this

segment's behavior and predisposition is likely to he very

expensive, and even then, the probability of success is low.

ever, are more fully realized when

the PCT score is combined with a

measure of past behavior. As Back-

man and Crompton

(1991 a,

b) and

Pritchard et al. (1999) demon-

strated,

combining attitude loyalty

grams that account for varying lev-

els of attachment held by fans. The

varying attitude-behavior combina-

tions represented in each cell in

Figure

1

suggest that different ap-

proaches to changing or maintain-

ing current levels of loyalty are re-

quired for each segment (see Table

2).

The following sections discuss

specific marketing strategies and

tactics for optimizing the strength of

fans'

attachment to a team for each

of the four loyalty segments.

High-Loyalty Segment

Description

In the upper left quadrant of Figure

1 are the truly loyal fans

(i.e.,

high

loyalty). Fans in this segment score

high on the PCT scale

(i.e.,

high at-

titudinal loyalty) and exhibit strong

behavioral loyalty

(e.g.,

attending

games, watching games on televi-

sion).

For these fans, the relation-

ship with the team has probably be-

come a significant part of their

lives,

and they are unlikely to

change their behavior or level of

commitment. However, the loyalty

level of this group may decrease

slowly over time if this segment is

ignored by marketers or may de-

crease more quickly if something

very drastic happens.

Strategy

A reinforcement strategy is the best

means for marketing to the highly

loyal fans (Pritchard et

al.,

1999;

Sheth,

1987). This strategy should

focus on reinforcing existing cogni-

Table

2.

Suggestions

for

Marketing

to the

Four Loyalty Segments

Segment Suggestions

High Loyalty

Spurious Loyalty

Latent Loyalty

Low Loyalty

Marketers should use a reinforcement strategy that includes reinforcing behavioral loyalty

through economic incentives and attitudinal loyalty through personalized encouragement. This

strategy is designed to increase the yield from this segment and to avoid any chances of losing

the segment.

Marketers should focus on increasing the fans' psychological commitment through the use of a

rationalization strategy. This can be done by promoting the positive attributes of the product or

service, getting the fans to articulate why they support the team, and/or coupling attendance

with support of

a

relevant social cause.

Marketers should focus on increasing the positive behaviors of the latently loyal fan by using a

market inducement strategy. This can be done by removing significant barriers to behavior and

by offering economic incentives to engage in certain behaviors.

Although some might suggest marketers use a confrontation strategy, which requires a direct at-

tack on the fan's existing attitudes, others believe this may only lead to strengthening the fan's

low level of commitment. Many strategists instead recommend focusing on using either a ratio-

nalization strategy to increase commitment or an inducement strategy to increase behavior as a

first step to high loyalty.

22 Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

tions,

allaying the potential for disso-

nance to occur (Pritchard et al.,

1999;

Sheth, 1987). Because they

are so valuable to the

team,

mar-

keters want to avoid a situation in

which highly loyal fans would de-

crease their behavior or reconsider

their allegiance to their favorite

team.

Moreover, marketers want to

focus on increasing the behavior of

these loyal fans

(e.g.,

number of

games attended, amount of mer-

chandise purchased) and increasing

the strength of their commitment.

Therefore, the reinforcement strategy

involves a two-pronged approach.

First, behavioral loyalty can be

rein-

forced extrinsically through eco-

nomic incentives

(e.g.,

discounts,

value-added services). Second, psy-

chological reinforcement based on

intrinsic rewards can be provided by

personalized encouragement

(e.g.,

newsletters, VIP treatment). The ob-

jective is to progressively increase

the yield from these best consumers

by developing a long-term, interac-

tive,

value-added relationship.

For example, the San Diego

Padres have developed a successful

program for rewarding their most

loyal customers

("With

Frequency,"

1996). Recently, this Major League

Baseball team developed a loyalty

program designed to reward frequent

attendance, as well as to encourage

fans to attend as many games as pos-

sible.

The Padres reward fans by al-

lowing those who attend games to

register for membership in the Com-

padres Club. Based on frequency of

game attendance, club members

earn points

("hits")

toward increas-

ingly attractive prizes, including ex-

clusive autograph sessions and in-

clusion in pregame chalk talks.

Registration for club membership

also allows the Padres to identify

their most loyal customers, to send

customized newsletters, and to so-

licit consumer satisfaction feedback

from these most desirable fans.

Spurious-Loyalty Segment

Description

Spuriously loyal fans, those in the

upper right quadrant of Figure 1,

are fans who exhibit high levels of

behavioral loyalty, but score low on

the PCT scale. These fans may ap-

pear to most observers to be loyal

fans of the team because they be-

have in the same manner as the

truly loyal fans

(e.g.,

frequently at-

tending games, frequently watching

games on television). However, they

are not committed fans of the fa-

vorite team and could drop out at

any point with little dissonance.

There may be a number of reasons

for this high level of behavior ac-

companied by low commitment,

such as (a) they attend ganies pri-

marily because friends or family

want to attend; (b) they attend

games of the home team, but are

fans of

a

team in another location;

(c) games are a relatively cheap

source of entertainment; (d) they are

given the tickets for free (by an em-

ployer or another business); or

(e) they go to the game for other

reasons

(e.g.,

business interactions,

socializing, drinking, gambling).

Strategy

With spuriously loyal fans, the strat-

egy would be to increase the psy-

chological commitment to the team

they are already supporting behav-

iorally. Again, increased attitudinal

loyalty among this segment is ex-

tremely important because these are

generally the fans who will stop

supporting the team when some-

thing goes wrong

(e.g.,

team perfor-

mance decreases; a popular player

is traded). Sheth (1987) recom-

mends a market rationalization

strategy as a way to strengthen con-

sumers' commitment toward a

prod-

uct they are already buying. The in-

tent is to create rationalized reasons

to justify their behavior.

One approach is to focus on pro-

moting the attributes of the product

or service (Sheth, 1987) in an at-

tempt to provide the spuriously loyal

fan with rational reasons why he or

she should support the team

(e.g.,

first-class tradition, fan-friendly

team). Second, it would also be

helpful to get the fans "to articulate,

at least on a rationalized basis, why

they buy or use the product/service"

(Sheth,

1987, p. 27). Prior research

suggests that as consumers try to jus-

tify their purchase, they tend to be-

come more committed to the

prod-

uct or service they purchased

(Schiffman & Kanuk, 1997).

Third,

coupling attendance with

support for a relevant social cause

may be an important rationalized

reason for some spuriously loyal

fans.

An emerging strategy, called

alignment marketing, attempts to

improve a brand or company's for-

tunes by linking it to some highly

valued celebrity or cause (lEC,

1995). Alignment marketing is based

on the belief that if an organization

is able to build a link in the con-

sumer's mind between the product

name and a cause that is of great

importance to that consumer

(e.g.,

feeding and sheltering the homeless,

civic pride), then there is a strong

probability that the consumer's per-

ception of that particular brand or

product will improve. This strategy

may also provide the basis for fans

to rationalize

and,

therefore,

strengthen their emotional commit-

ment to a team. A

team,

for exam-

ple,

that demonstrates its commit-

ment to helping battered women by

pledging a portion of each ticket

sold to fund or construct a new

shel-

ter provides the spuriously loyal fan

one more important reason to care

about the organization and to attend

games. In a college sport setting, it

may be possible to focus on the

team's high graduation rate, suggest-

ing this is a program that values ed-

ucation first, or focus on the number

of local players on the team, playing

on the belief of some that it is im-

portant to support local "kids."

Latent-Loyalty Segment

Description

In contrast to spuriously loyal fans,

latently loyal fans (lower left quad-

rant of Figure 1) are those who

scored high on the PCT scale, but

exhibit low levels of behavioral loy-

alty. Although these fans are un-

likely to change their team alle-

giance, they do not exhibit many of

the behaviors that would benefit the

team

(e.g.,

attending games). There

may be a number of reasons for

Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 23

their low level of behavior includ-

ing the high cost of some games,

the time it takes to attend a game,

and the accessibility of games.

Many people in this segment may

constitute what Muliin et al. (1993)

refer to as "media consumers,"

those whose commitment is high

but whose behaviors related to their

favorite team are limited to more

passive, indirect involvement

through watching or listening to

games and reading about the team

in the newspaper. Moreover, fans

who live outside their favorite

team's region may have difficulty

obtaining even media access to

games and would, therefore, exhibit

even less loyalty-related behavior.

Strategy

According to Sheth (1987), the mar-

ket inducement strategy is most use-

ful in reaching latently loyal con-

sumers. To induce these fans to

move toward more active, direct

participation and into the

"high-

loyalty" group, where their behav-

ior matches their attitude, Sheth

recommends two approaches. First,

the facilitation of inducement in-

volves eliminating any obstacles

that prevent consumers from pur-

chasing the product or service they

like.

"It involves removal of time,

place and possession barriers in tar-

get segments" (Sheth, p. 26). Sec-

ond,

economic incentives are an-

other way to induce people to

engage in behavior toward which

they have a positive predisposition.

Incentives could include a range of

sales and promotional programs,

such as coupons, ticket-price dis-

counts, and the offering of lottery

prizes.

The Milwaukee Brewers initiated

a ticket-package campaign intended

to reach fans who had not histori-

cally purchased season ticket pack-

ages (Eisengerg, 1993). Rather than

just offering traditional

full-

(81

games) or halfseason (40 games)

ticket options, the Major League

Baseball club created a series of

miniticket packages (13 games) tai-

lored to the specific interests and

abilities of their fan base (Eisen-

gerg).

In effect, fans were offered

the opportunity to attend Brewer

games on the dates

(e.g.,

weekdays,

Saturdays, and/or Sundays only)

they most preferred and at the time

they most preferred (afternoon or

evenings) and to watch the combi-

nation of teams they most preferred,

all at a substantial discount. The

new program was enormously suc-

cessful,

increasing new or first-time

season ticket sales by

41%

(Eisen-

gerg).

Meanwhile, teams may also

want to focus on increasing the

media coverage of their games in

order to reach fans who are not

geographically close to their fa-

vorite team. For example, many

college sport teams are focusing on

increasing the radio reach of their

games

(e.g.,

picking stations with a

wider reach, offering games over

the internet) and on increasing ac-

cess to televised games

(e.g.,

pay-

per-view) in order to reach their

fans and alumni who do not live in

their geographic region.

Low-Loyalty Segment

Description

Finally, low-loyalty fans (lower right

quadrant of Figure 1) are those who

scored low on the PCT scale and ex-

hibited low levels of behavioral loy-

alty. These fans are not committed

to the team and rarely support the

team by attending games or by

watching on television. It is likely

that when these fans do attend

games, it is merely for some reason

unrelated to the team itself

(e.g.,

to

watch a particular player, to watch

the opposing

team,

to socialize).

They could drop out, and this would

have no psychological impact on

them and would result in almost no

change in their daily lives.

Strategy

Low-loyalty consumers are the

most challenging segment. These

infrequent or nonattending patrons

hold,

at best, an ambivalent

atti-

tude toward the sports team. Con-

verting this segment's behavior and

predisposition is likely to be very

expensive, and even

then,

the

probability of success is low. Sheth

(1987) recommended a confronta-

tion strategy for reaching this disen-

franchised market. This approach

requires a direct attack on existing

attitudes of the consumer. How-

ever, achieving the desired change

may be very difficult. As Kiesler

(1971) points out, this approach

often results in a "boomerang ef-

fect" in which counterpersuasive

communication strengthens the re-

cipient's resistance to change.

Moreover, the confrontation

process is not a cost-efficient ap-

proach in terms of actually turning

consumer attitudes and behavior.

A second approach would be to

allow the movement of fans toward

genuine loyalty to be undertaken

gradually, concentrating on either

behavioral or attitudinal change first

(i.e.,

movement to spuriously or la-

tently loyal). Marketers could focus

on increasing the behavior first. This

could be done by offering packages

to various groups

(e.g.,

families,

businesses) that may result in the

low-loyalty fans attending more

games, by selling the game to the

low-loyalty fans as part of an entire

entertainment package, or by focus-

ing on attributes other than the team

(e.g.,

opposing

team,

star player). In

addition,

the rationalization strategy

could be used to first focus on build-

ing a level of commitment to the

team.

However, both of these ap-

proaches are unlikely to produce

highly successful results with this

segment and may not be the best

use of resources. Consequently,

many strategists recommend focus-

ing on the more attractive, less resis-

tant spuriously loyal and latently

loyal fans (Hawkins, Best, & Coney,

1995;

Rothschild, 1987).

Summary

In general, the PCT scale can be

very helpful to sport marketing

practitioners who wish to use psy-

chographic information to better

target their fans and to better assess

the current feelings about the team

among fans and/or local residents.

The scale is relatively short (it could

even be used as part of

a

phone sur-

vey),

easy to administer, and easy to

24 Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly

adjust to different team sports at dif-

ferent competition levels. Use of the

scale will allovk' marketers to better

assess loyalty toward their team and

to be better prepared for their fu-

ture.

The scale can also be useful in

assessing the impact of past and

current marketing and customer ser-

vice efforts. Sport marketers who

wish to move beyond the "build it

and they will come" philosophy of

sport marketing should find this

scale useful in moving their market-

ing efforts forward.

References

Baade, R. A., & Tiehan, L.

J.

(1990). An

analysis of major league baseball atten-

dance:

1969-1987. Journal of

Sport

and

So-

cial

issues,

14, 14-32.

Backman,

S.

J.,

& Crompton,

J.

L. (1991a).

The usefulness of selected variables for pre-

dicting activity loyalty.

Leisure

Sciences,

13,

205-220.

Backman,

S.

J.,

& Crompton,

J.

L.

(1991

b).

Using a loyalty matrix to differentiate be-

tween

high,

spurious, latent and low loyalty

participants in tow leisure services. Journal

of

Park

and

Recreation

Administration, 9,

117.

Bureau of Economic Analysis (1996, Janu-

ary/February).

Survey

of current

business,

6.

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Com-

merce.

Churchill,

C. A., )r. (1979). A paradigm for

developing better measures of marketing

constructs. Journal of Marketing

Research,

16,64-73.

Cronbach,

L.

J.

(1951). Coefficient alpha

and the internal structure of

tests.

Psychome-

trika,

76,297-334.

Crosby, L. A., & Taylor,

J.

R. (1983). Psy-

chological commitment and its effect on

postdecision evaluation and preference sta-

bility among voters. Journal of

Consumer

Re-

search,

9,

413-431.

Dawis, R. V. (1987). Scale construction.

Journal of

Counseling

Psychology,

34,

481-489.

Day, C. S. (1969). A two dimensional con-

cept of brand loyalty. Journal of Advertising

Research,

9, 29-35.

Dick, A. S., & Basu, K. (1994). Customer

loyalty: Toward an integrated conceptual

framework. Journal of

the

Academy of Mar-

keting

Science,

22, 99-113.

Eisengerg,

J.

(1993, October). Small-market

success: How the Milwaukee Brewers sold

43%

more season tickets.

Team

Marketing

Report,

pp. 9-11.

Eisler, P. (1997, March 27). Guys go awry

over losing. USA

Today,

p. 1D.

Evans,

J.

R., & Berman, B. (1994). Market-

mg(6th ed.). New York: Macmillan.

Fazio,

R. H. (1995). Attitudes as object-

evaluation associations: Determinants, con-

sequences, and correlates of attitude accessi-

bility. In R. E. Petty &

J.

A. Krosnick (Eds.),

Attitude

strength:

Antecedents

and

conse-

quences

{pp.

247-282). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Guttmann,

A. (1986).

Sports

spectators.

New York: Columbia University.

Haugtvedt, C.

P.,

& Petty, R. E. (1992). Per-

sonality and persuasion: Need for cognition

moderates the persistence and resistance of

attitude changes. Journal of

Personality

and

Social

Psychology,

63, 308-319.

Haugtvedt, C. P, & Wegener, D. T. (1994).

Message order effects in persuasion: An

atti-

tude strength perspective. Journal of

Con-

sumer

Research,

21, 205-218.

Havitz, M., & Howard, D. R. (1995). How

enduring is enduring involvement? A seasonal

examination of three sports activities.

Journal

of

Consumer

Psychology,

4, 255-276.

Hawkins, D. I., Best, R.

J.,

& Coney, K. A.

(1995).

Consumer

behavior:

Building mar-

keting

strategy

(7th ed.). New York: McGraw-

Hill.

Howard,

D. R., & Crompton,

J.

L. (1995).

Financing

sport.

Morgantown, WV: Fitness

Information Technology, Inc.

Howard,

D. R., & Thompson, P. (1984).

The critical importance of the distribution

variable in marketing strategy.

Visions

in

Leisure

and

Business,

3{2), 34-40.

International Events Group (1995). lEC's

complete guide to

sponsorship.

Chicago, IL.

Jacoby,

J.,

& Chestnut, R. W. (1978). Brand

loyalty:

Measurement

and

management.

New York: Wiley.

Jacoby,

J.,

& Kyner, D. B. (1973). Brand

loyalty V. repeat purchase behavior. Journal

of Marketing

Research,

10, 19.

Kiesler, C. A. (1971).

The

psychology of

commitment. New York: Academic Press,

Inc.

Kiesler, C. A., & Mathog,

J.

(1971). Resis-

tance to influence as a function of number of

prior consonant acts: A test. In C. A. Kiesler

(Ed.),

The

psychology of

commitment.

New

York: Academic Press, Inc.

Kiesler, C. A., & Sakamura,

J.

(1966). A test

of a model for commitment. Journal of

Per-

sonality and Social

Psychology,

3, 349-353.

Kraus,

S.

J.

(1995). Attitudes and the pre-

diction of behavior: A metaanalysis of the

empirical literature.

Personality

and

Social

Psychology

Bulletin, 21, 58-75.

Lee,

H. M. (1983). The sport fan and team

loyalty in ancient Rome.

ARETE:

The Journal

of Sport

Literature,

1, 139-145.

Mihoces, G. (1995, May 23). Fans fight

poststrike hangover. USA

Today,

pp. C1-C2.

Mullin,

B.

J.,

Hardy, S., & Sutton, W. A.

(1993).

Sport

marketing.

Champaign, IL:

Human Kinetics Publishers.

Murrell,

A.

J.,

& Dietz, B. (1992). Fan sup-

port of sports teams: The effect of

a

common

group identity. Journal of

Sport

and

Exercise

Psychology,

/

4,

28-39.

National Sporting Goods Association.

(1996).

The sporting goods

market in 1995.

ML.

Prospect, IL: National Sporting Goods

Association.

Nunnally,

J.

C, & Bernstein, I. H. (1994).

Psychometric

theory

{3rd

ed.). New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Olson,

J.

C, & Jacoby,

J.

(1971). A con-

struct validation study of brand loyalty. Pro-

ceedings

of

the

American

Psychological

As-

sociation, 6, 657-658.

Petty, R. E., Haugtvedt, C.

P.,

& Smith,

S. M. (1995). Elaboration as a determinant of

attitude strength: Creating attitudes that are

persistent, resistant, and predictive of behav-

ior. In R. E. Petty &

J.

A. Krosnick (Eds.),

Atti-

tude

strength:

Antecedents

and

conse-

quences

{pp.

93-130). Mahwah, NJ:

Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Pritchard,

M. P, Havtiz, M. E., & Howard,

D. R. (1999). Analyzing the commitment-loy-

alty link in service contexts.

Journal

of

the

Academy of Marketing

Science,

27, 333-348.

Rosenberg, M.

J.

(1965). When dissonance

fails:

On eliminating evaluation apprehen-

sion from attitude measurement. Journal of

Personality

and Social

Psychology,

1,

28-43.

Rothschild,

M. L. (1987). Marketing com-

munications:

From fundamentals

to

strategies.

Lexington,

MA: D. C. Heath & Company.

Schiffman,

L. G., & Kanuk, L. L. (1997).

Consumer

behavior

{6th

ed.). Upper Saddle

Run,

NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Sheth,

J.

N. (1987). A normative theory of

marketing practice. In G. Frazier & N. Sheth

(Eds.),

Contemporary views of

marketing

practice

{pp.

19-31). Lexington, MA: Lexing-

ton Press.

Sloan,

L. R. (1989). The motives of sports

fans.

In

J.

H. Goldstein (Ed.),

Sports,

games,

and

play:

Sociological and psychological

viewpoints {2nd ed.; pp. 175-240). Hills-

dale,

NJ: Lawrence Eribaum Associates.

Smith,

G.

J.,

Patterson, B., Williams, T.,

& Hogg,

J.

(1981,

September). A profile of

the deeply committed male sports fan. Arena

Review,

5, 26-44.

U.S. Bureau of

Census.

(1993). Statistical

abstract

of

the

United

States:

7 993

(113th

ed.).

Washington, DC: U.S. Department of

Commerce.

Wakefield,

K. L., & Sloan, H.

J.

(1995). The

effects of team loyalty and selected stadium

factors on spectator attendance. Journal of

Sport

Management,

9, 153-172.

With frequency promotion and database

marketing.

Padres expect fans to have many

happy returns. (1996, March).

Team

Market-

ing

Report,

pp. 3, 8.

Zillman,

D., & Paulus, P. B. (1993). Specta-

tors:

Reaction to sporting events and effect

on athletic performance. In R. N. Singer, M.

Murphey, & L. K. Tenant (Eds.), Handbook of

research

on

sport

psychology

{pp.

600-619).

New York: Macmillan.

Volume 9 • Number

1

• 2000 • Sport Marketing Quarterly 25