Progress

and

Pitfalls

in

Underrepresented

Minority

Recruitment:

Perspectives

from

the

Medical

Schools

Jaya

R.

Agrawal,

MD,

MPH;

Sorina

Vlaicu,

MD,

PhD;

and

Olveen

Carrasquillo,

MD,

MPH

Boston,

Massachusetts;

Arlington,

Virginia;

and

New

York,

New

York

Financial

support:

Funding

from

the

Office

of

Minonty

Health

of

the

Department

of

Health

and

Human

Services

(OMH)

and

the

American

Medical

Student

Association

(AMSA).

Dr.

Carrasquillo's

effort

on

this

project

was

supported

by

a

Cen-

ter

of

Excellence

Grant

from

the

National

Center

for

Minority

Health

and

Health

Disparities

(NCMHD,

MD00206

P60).

Purpose:

To

assess

current

initiatives

at

U.S.

medical

schools

to

recruit

underrepresented

minorties

(URM)

and

to

identify

perceived

barriers

to

enrollment

of

URM

students.

Methods:

We

developed

a

survey

that

was

mailed

to

the

dean

of

Student

Affairs

of

all

U.S.

allopathic

and

osteopathic

medical

schools

in

2002.

Respondents

were

asked

to

list

their

schools'

URM

recruitment

programs

and

rate

the

effective-

ness

of

these

programs.

They

were

also

asked

to

indicate

barriers

to

URM

recruitment

from

a

list

of

37

potential

barriers

and

rate

their

overall

success

with

URM

recruitment.

Results:

The

study

had

a

59%

response

rate.

All

schools

report-

ed

a

wide

varety

of

initiatives

for

URM

recruitment

with

.50%

of

all

schools

using

each

of

the

11

strategies.

The

three

most

commonly

listed

barriers

to

URM

recruitment

were

MCAT

scores

of

applicants

(90%),

lack

of

minority

faculty

(71%)

and

lack

of

minority

role

models

(71%).

Most

schools

rated

their

recruitment

efforts

highly;

on

a

scale

of

1

to

10

(10

being

very

successful),

the

average

score

was

an

8.

Conclusion:

While

schools

continue

to

invest

tremendous

efforts

in

recruiting

minorty

applicants,

admissions

crtera,

lack

of

URM

faculty

and

the

need

for

external

evaluation

remain

important

bariers

to

achieving

a

diverse

physician

workforce.

Key

words:

underrepresented

minorities

*

medical

school

admissions

©

2005.

From

the

Deportment

of

Medicine,

Brigham

and

Women's

Hospital,

Boston,

MA

(Agrawal);

the

School

of

Public

Policy,

George

Mason

University,

Arlington,

VA

(Vlaicu,

presently

at

The

University

of

Western

Ontario,

London,

Ontario,

Canada)

and

the

Center

for

the

Health

of

Urban

Minorities,

Colum-

bia

University

Medical

Center,

New

York,

NY

(Carrasquillo).

Send

correspon-

dence

and

reprint

requests

for

J

NotI

Med

Assoc.

2005;97:1226-1231

to:

Olveen

Carrasquillo,

MD,

MPH,

Division

of

General

Medicine,

Columbia

Uni-

versity

Medical

Center,

PH

9E

Room

105,

622 W.

168th

St.;

phone:

(212)

305-

9782;

fax:

(212)

305-9349;

e-mail:

BACKGROUND

Despite

nearly

a

quarter

century

of

diversity

ini-

tiatives

by

government

agencies,

medical

schools

and

other

organizations,

the

percentage

of

medical

students

who

belong

to

historically

underrepresent-

ed

racial

and

ethnic

minority

(URM)

groups

has

remained

fairly

uniform,

fluctuating

from

8.0%

to

12.5%,'

while

representation

of

these

same

minority

groups-African

Americans,

Hispanic

Americans

and

Native

Americans-in

the

U.S.

population

has

reached

26%

and

continues

to

grow.2

The

Sullivan

Commission

on

Diversity

in

the

Health

Workforce

concluded

"failure

to

reverse

these

trends

could

place

the

health

of

at

least

one-

third

of

the

nation's

citizens

at

risk."3

Furthermore,

the

Institute

of

Medicine

(IOM)

has

recommended

"institutional

and

policy

level

change"

aimed

at

increasing

the

proportion

of

URMs

among

the

health

professions

as

part

of

a

multifaceted

strategy

to

reduce

racial

and

ethnic

disparities

in

healthcare.4

Understanding

the

causes

of

difficulties

in

recruit-

ment

of

URM

students

has

been

the

focus

of

much

commentary

and

limited

empirical

analyses.

We

con-

tribute

to

this

work

through

a

national

survey

of

med-

ical

schools

that

aims

to

assess

self-reported

efforts

by

the

medical

schools

to

recruit

URM

students,

iden-

tify

barriers

which

the

schools

report

in

recruiting

URM

students

and

examine

the

opinions

of

adminis-

trators

regarding

their

success

at

URM

recruitment.

The

only

other

similar

survey

of

which

we

are

aware

is

the

2004

study

by

Dinan

et.

al.,

commissioned

by

the

Sullivan

Task

Force.3

However,

they

were

only

able

to

obtain

limited

data

from

most

schools,

and

the

focus

of

their

analysis

was

on

the

subset

of

14

medical

schools

they

identified

as

having

innovative

programs

aimed

at

increasing

diversity.

METHODS

Instrument

Development

In

developing

the

American

Medical

Student

Association

Diversity

Survey

(AMSA-DS),

we

first

1226

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

UNDERREPRESENTED

MINORITY

RECRUITMENT

conducted

a

review

of

the

relevant

literature

using

a

Medline

search

for

combinations

of

the

following

key

words:

"underrepresented

minorities,"

"medical

school

admissions,"

"diversity,"

"recruitment,"

"retention"

and

"representation."

Included

were

all

articles,

both

research

studies

and

commentary,

pub-

lished

between

1985

and

2000

and

having

any

dis-

cussion

of

minority

representation

in

medical

schools.

A

summary

of

the

findings

in

these

articles

with

an

annotated

bibliography

were

presented

to

AMSA's

Diversity

Coalition,

a

group

of

eight

mem-

bership-based

medical

associations

with

a

stated

commitment

to

diversity

in

their

mission

statement

(Tablel).

Representatives

of

these

organizations

drafted

the

AMSA-DS.

In

the

fall

of

2001,

the

instrument

was

pilot-tested

at

four

medical

schools.

The

deans

of

students

at

each

of

these

schools

were

asked

to

comment

on

content,

length

and

clarity

of

the

survey

and

survey

items.

Based

on

their

feed-

back,

the

instrument

was

revised

by

modifying

some

questions,

adding

certain

items

and

excluding

other

questions.

The

final

survey

contained

100

items

and

took

approximately

20

minutes

to

complete

[instru-

ment

available

from

Carrasquillo

(author)].

Survey

items

included:

1.

A

list

of

37

potential

barriers

to

URM

recruit-

ment

with

respondents

being

asked

to

check

all

that

applied

to

their

school;

2.

A

list

of

11

URM

recruitment

programs

with

respondents

being

asked

to:

a)

note

whether

the

program

was

in

place

at

their

institution

and

b)

rate

the

effectiveness

of

the

program

by

using

a

modified

four-point

Likert

scale

(not

effective,

effective,

very

effective

and

don't

know).

The

survey

also

included

one

question

asking

for

an

overall

assessment

of

the

school's

success

in

the

recruitment

of

URM

students

on

a

scale

of

1

to

10

(10

being

best).

Lastly,

we

undertook

this

project

during

a

nationwide

discussion

led

by

the

Association

of

American

Medical

Colleges

on

redefining

and

expanding

the

term

"underrepre-

sented

minority."

Therefore,

an

additional

ques-

tion

asked

medical

schools

if

they

would

like

to

target

for

recruitment

any

of

several

listed

addi-

tional

minority

and

disadvantaged

groups

[other

minorities

(e.g.

Asians,

non-URM

Hispanics),

women,

gay/lesbian/transgender

students,

dis-

abled,

economically

disadvantaged,

second-

career

professionals

and

an

open-ended

question

on

other

groups].

In

spring

2002,

we

mailed

the

AMSA-DS

and

an

accompanying

letter

signed

by

the

presidents

of

AMSA

and

the

Student

National

Medical

Associa-

tion

(SNMA)

to

the

deans

of

student

affairs

of

all

144

accredited

allopathic

and

osteopathic

medical

schools.

Deans

were

asked

to

identify

their

school

by

name

for

purposes

of

follow-up

only,

with

assur-

ance

of

confidentiality.

In

many

cases,

the

survey

was

forwarded

to

the

dean

of

admissions

or

minority

affairs

faculty

who

responded

to

the

survey.

A

post-

card

reminder

was

sent

at

the

four-week

mark

and

the

instrument

was

faxed

to

schools

at

the

eight-

week

mark

with

telephone

follow-up.

Schools

responded

to

the

instrument

via

mail

or

fax.

The

data

collection

period

was

closed

10

weeks

after

the

ini-

tial

mailing.

Surveys

were

collected

by

independent

consultants

at

the

School

of

Public

Policy

at

George

Mason

University

and

entered

into

a

database

with

identifying

information

removed.

Because

the

goal

of

the

study

was

to

assess

the

viewpoints

and

efforts

of

schools

struggling

with

enrollment

of

traditional

URM

students,

we

did

not

include

schools

who

already

enrolled

a

high

proportion

of

URM

students.

Thus,

schools

indicating

that

they

were

a

historically

black

medical

school

or

located

in

Puerto

Rico

were

excluded

from

this

analysis.

Statistical

Analysis

We

compared

differentials

in

characteristics

among

responding

and

nonresponding

medical

schools

using

Chi-squared

analyses.

We

analyzed

the

percentage

of

URM

students

at

each

school

as

a

continuous

variable,

and

correlates

of

URM

enroll-

ment

with

categorical

variables

were

examined

using

t

tests

with

Bonferoni

adjustment

for

multiple

comparisons.

We

present

descriptive

data

on

exist-

ing

initiatives

at

medical

schools

to

recruit

URM,

perceived

barriers

to

enrollment

of

URM

and

inter-

est

in

recruiting

other

minority

students

as

percent-

ages.

Self-reported

success

at

recruiting

URM

stu-

dents

was

not

normally

distributed

(as

determined

with

visual

examination

of

data

plots

and

the

Wilk-

Shapiro

test).

Thus,

we

used

Spearman

correlation

coefficients

to

examine

the

association

between

self-

reported

success

and

the

percentage

of

URM

stu-

dents

at

each

school.

All

analyses

were

performed

using

SAS

v8.

Table

1.

Organizations

that

participated

in

the

American

Medical

Student

Diversity

Coalition

1.

Student

National

Medical

Association

2.

National

Medical

Association

3.

National

Network

of

Latin

American

Medical

Students

4.

National

Hispanic

Medical

Association

5.

American

Medical

Student

Association

6.

American

Medical

Women's

Association

7.

Association

of

American

Indian

Physicians

8.

Gay

and

Lesbian

Medical

Association

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

1227

UNDERREPRESENTED

MINORITY

RECRUITMENT

RESULTS

The

overall

response

rate

was

59%

(86

out

of

144),

which

compares

favorably

with

the

41%

response

rate

obtained

by

Dinan

et. al.

in

their

medical

school

sur-

vey.4

Our

response

rate

did

not

differ

by

geographic

region

but

was

higher

among

osteopathic

schools

than

allopathic

schools

(68%

versus

55%,

P<0.05).

Of

the

responding

institutions,

50

identified

themselves

as

public

and

28

as

private;

eight

schools

did

not

respond

to

this

survey

question.

Among

the

60

schools

respond-

ing

to

the

question

on

the

percentage

of

entering

stu-

dents

who

were

URM,

the

mean

was

10.4%

(median

10.0,

inter-quartile

range

6-15%).

This

figure

is

similar

Table

2.

Medical

school

reported

barriers

to

underrepresented

minority

recruitment

Barrier

Percent

Listing

as

Barrier

at

Their

Institution

Legal/Policy/Regulatory

Court

decisions

33%

State/local

policies

19%

State

legislation

limiting

affirmative

action

14%

Educational

Low

MCAT

scores

90%

Low

undergraduate

GPA

60%

Poor

preparation

in

sciences

55%

Absence

of

high

school

science

interest

programs

46%

Low

educational

achievement

40%

Lower

quality

of

schools

previously

attended

34%

Lower

level

of

academic

achievement

among

parents

30%

Poor

communication

skills

19%

No

participation

in

service-oriented

extracurricular

activities

17%

Socio-cultural

Absence

of

role

models

77%

Lack

of

peer/community

support

45%

State/area

population

not

diverse

37%

Negative

parental

and

cultural

attitudes

regarding

careers

19%

Financial/Economic

Lack

of

financial

aid

48%

Parental

income

level

39%

Difficulties

in

finding

financial

resources

for

your

school's

programs

28%

No

financial

travel

assistance

to

the

required

admission

interview

27%

High

application

fees

14%

Housing

issues

12%

Recruitment/Admission

Not

enough

minority

faculty

members

71%

Other

schools

in

the

area

targeting

URM

majoring

in

sciences

39%

Absence

of

summer

enrichment

programs

at

your

school

27%

Race/ethnicity/gender

composition

of

the

admission

committee

22%

Absence

of

partnerships

with

private

and

public

organizations

20%

Lack

of

mentorship

programs

20%

Lack

of

career

development

outreach

16%

No

URM

student

recruiters

13%

Complex

application

process

10%

No

pre-admission

counseling

and

application

assistance

7%

Absence

of

an

office

of

minority

and/or

multicultural

affairs

7%

No

faculty

member

designated

to

address

issues

of

concern

from

URM

students

7%

to

the

10.9%

URM

enrollment

at

all

U.S.

medical

schools

in

2001.1

The

mean

percentage

of

URM

did

not

differ

significantly

among

private

schools

versus

pub-

lic

schools

or

at

osteopathic

versus

allopathic

schools.

Phone

contact

with

nonresponding

schools

found

that

that

lack

of

time

or

staff

resources

to

fill

out

the

survey

by

the

deadline

was

the

most

common

reason

for

lack

of

participation.

However,

two

schools

expressed

con-

cern

that

providing

data

on

this

topic

would

leave

them

legally

vulnerable.

Barriers

to

Recruiting

Minority

Students

Of

the

37

possible

barriers

to

URM

recruitment,

1228

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

UNDERREPRESENTED

MINORITY

RECRUITMENT

only

five

were

cited

as

significant

by

at

least

half

of

the

responding

schools

(Table

2).

Of

these,

three

barriers

were

related

to

educational

preparation,

with

low

MCAT

scores

being

mentioned

by

90%

of

schools.

The

other

commonly

listed

educational

barriers

were

low

grade

point

average

(GPA)

(60%)

and

poor

preparation

in

the

sciences

(55%).

However,

the

second

and

third

most

commonly

listed

barriers

to

URM

recruitment

were

related

to

minority

faculty

representation

in

the

medical

school.

In

fact,

the

absence

of

role

models

and

lack

of

minority

faculty

members

were

noted

as

signif-

icant

barriers

by

three-quarters

of

respondents.

Financial

barriers

were

cited

by

less

than

half

of

respondents,

and

on

the

whole,

schools

did

not

feel

that

their

recruitment

process

or

institutional

quali-

ties

posed

a

problem-with

the

exception

of

lack

of

minority

faculty

members.

Interestingly,

although

our

study

was

conducted

prior

to

the

Supreme

Court's

recent

favorable

ruling

on

affirmative

action,

even

before

this

ruling,

less

than

one-third

of

respondents

cited

legal

issues

around

affirmative

action

as

a

significant

barrier.

Recruitment

Strategies

We

found

that

most

schools

have

a

wide

variety

of

initiatives

for

URM

recruitment

(Table

3).

Indeed,

each

of

the

11

URM

recruitment

strategies

listed

in

our

survey

were

present

in

at

least

half

of

the

schools.

Of

these,

preadmission

site

visits

to

med-

ical

schools

by

minority

applicants

(91%),

pre-

admission

counseling

(88%),

career

outreach

pro-

grams

to

communities

(83%),

financial

aid

(82%)

and

URM

student

early

identification

(77%)

were

the

most

commonly

utilized.

When

asked

to

rate

the

effectiveness

of

each

of

the

recruitment

programs

employed

by

their

schools,

less

than

half

of

the

schools

gave

any

of

these

specific

strategies

the

highest

rating

of

"very

effective",

with

two

notable

exceptions:

URM

student

recruiters

(61%

of

schools

rated

this

recruitment

strategy

as

"very

Table

3.

Medical

school

reported

recruitment

strategies

for

underrepresented

minority

students

Recruitment

Strategy

Percent

of

Schools

Percent

Rating

Program

with

Program

Very

Effective

Site

visit

to

school

(pre

admission)

91%

44%

Pre-Admission

Counseling

87%

40%

Career

development

outreach

in

primary

or

secondary

schools

81%

30%

Financial

Aid

80%

31%

Early

Targeting

of

Minority

Students

75%

38%

URM

Student

Recruiters

71%

61%

Enrichment

Programs

66%

56%

Community

Based

Education

Programs

64%

39%

Alumni

Involvement

64%

33%

Application

Assistance

61%

37%

Partnerships:

Education

or

Labor

State

Departments,

Foundations

44%

36%

effective")

and

enrichment

programs

for

minority

stu-

dents

(56%

of

schools

rated

this

strategy

as

"very

effective").

However,

few

schools

(<15%)

rated

any

of

the

11

strategies

as

being

totally

ineffective.

Of

the

11

strategies,

the

only

one

positively

correlated

with

the

percentage

of

URM

students

was

having

summer

enrichment

programs.

Among

the

36

schools

that

reported

having

such

a

program,

the

mean

percentage

of

entering

URM

students

was

12.5%

±

6%

versus

7.0%

±

4.8%

(p<0.01)

at

the

20

schools

that

did

not

report

having

such

a

program.

Other

Underrepresented

Minorities

When

schools

were

asked

about

interest

in

recruit-

ing

other

groups,

86%

said

they

were

interested

in

recruiting

economically

disadvantaged

students,

58%

were

interested

in

the

recruiting

racial/ethnic

minori-

ties

not

currently

designated

as

URM,

57%

in

women

and

42%

in

students

with

disabilities.

Fewer

schools

were

interested

in

attracting

second-career

students

(36%)

or

gay

and

lesbian

students

(24%).

When

asked

in

an

open-ended

way

what

other

groups

the

schools

were

interested

in

targeting,

the

most

frequent

answer

was

in

recruiting

regional

ethnic

minorities.

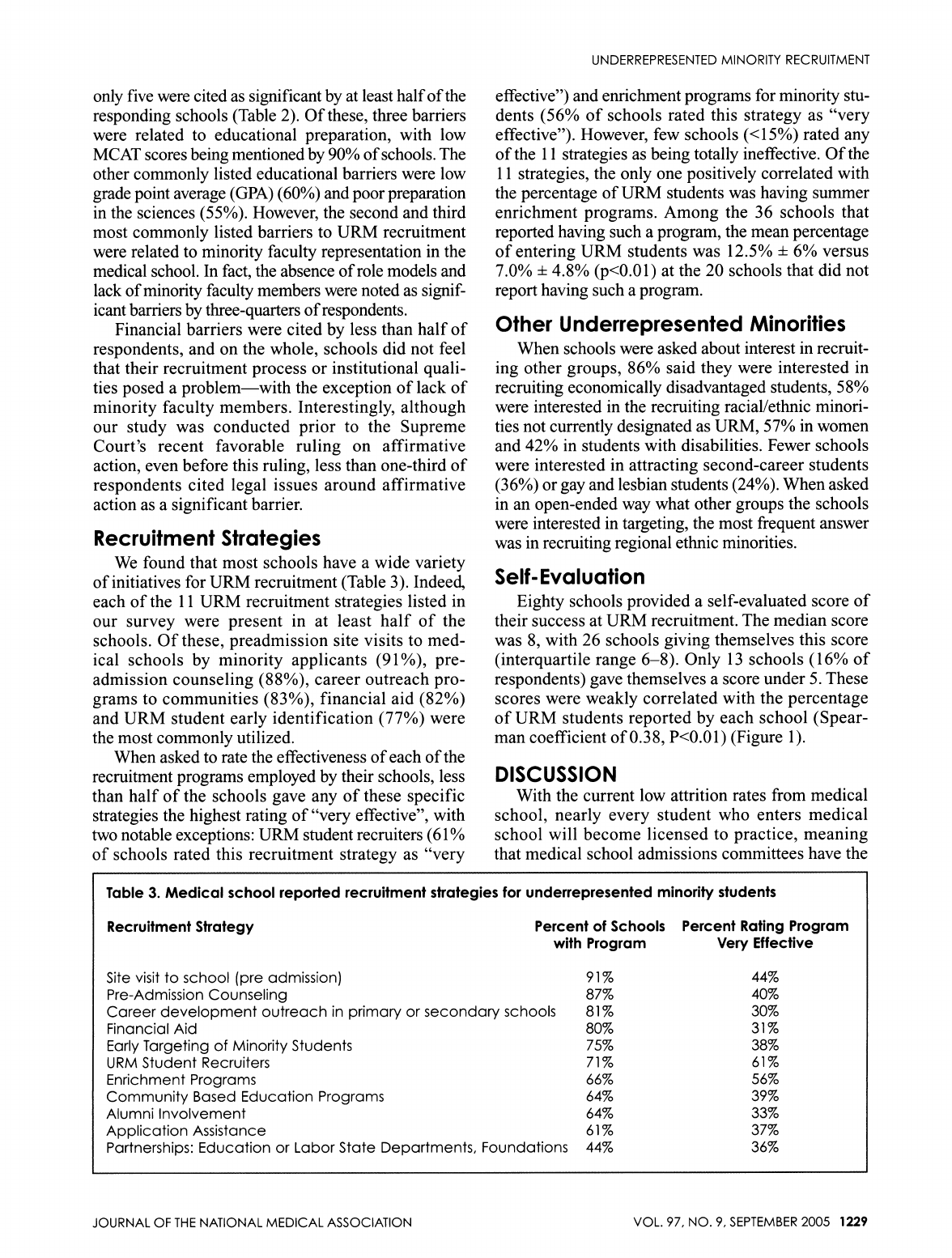

Self-

Evaluation

Eighty

schools

provided

a

self-evaluated

score

of

their

success

at

URM

recruitment.

The

median

score

was

8,

with

26

schools

giving

themselves

this

score

(interquartile

range

6-8).

Only

13

schools

(16%

of

respondents)

gave

themselves

a

score

under

5.

These

scores

were

weakly

correlated

with

the

percentage

of

URM

students

reported

by

each

school

(Spear-

man

coefficient

of

0.38,

P<0.01)

(Figure

1).

DISCUSSION

With

the

current

low

attrition

rates

from

medical

school,

nearly

every

student

who

enters

medical

school

will

become

licensed

to

practice,

meaning

that

medical

school

admissions

committees

have

the

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

1229

UNDERREPRESENTED

MINORITY

RECRUITMENT

sole

responsibility

of

choosing

the

nation's

future

physician

workforce.5

Our

study

examining

the

per-

ception

of

medical

schools

on

barriers

to

URM

recruitment

sheds

some

light

on

how

schools

make

admission

decisions

and

how

this

affects

diversity

in

the

classroom.

For

example,

low

GPA

and

MCAT

scores

among

URM

applicants

are

perceived

to

be

a

barrier

by

the

vast

majority

of

respondents,

suggest-

ing

that

schools

continue

to

place

significant

weight

on

these

admissions

criteria.

Concerns

regarding

overreliance

on

such

metrics

and

their

role

as

barriers

to

medical

school

diversity

have

existed

among

medical

educators

for

over

20

years.6

Yet

even

today,

expert

opinion

still

remains

divided

on

such

admissions

criteria,7-10

with

some

advocating

for

the

continued

role

of

the

MCAT

and

GPA

scores,

and

others

calling

for

the

abandonment

of

such

criteria

in

favor

of

"noncognitive

attributes"

(i.e.,

altruism,

maturity,

etc).

Most

recently,

the

Sul-

livan

Commission

on

Diversity

in

the

Health

Work-

force

recommended:

"medical

schools

should

reduce

their

dependence

upon

standardized

tests

in

the

admissions

process

...

and

the

MCAT

should

be

utilized

along

with

other

criteria

in

the

admissions

process

as

diagnostic

tools

to

identify

areas

where

qualified

health

professions

applicants

may

need

academic

enrichment

and

support."3

Our

study

also

underscores

the

importance

of

visi-

ble

URM

medical

school

faculty

and

students

in

the

building

of

a

diverse

physician

workforce

for

the

future.

Consistent

with

prior

reports,'

""2

a

large

propor-

tion

of

schools

noted

the

effectiveness

of

URM

stu-

dents

in

recruitment

and

the

absence

of

minority

facul-

ty

as

the

biggest

institutional

barrier

to

URM

recruitment.

However,

achieving

diversity

among

fac-

Figure

1.

Medical

school

self-evaluated

success

at

underrepresented

minority

student

recruitment

versus

the

percentage

of

entering

students

who

are

URM

30

l:

-

25-

a)*

2

20

-

15

-

z

0~~~~~~~~~~~~~

z-

*

102

S

)

*

2

a)

5-

*

t

a.

t,

t,

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Spearman

coefficient

0.38,

P<0.01

Self-Rated

Success

ulty

at

medical

schools

has

proved

challenging,

with

URM

faculty

currently

representing

only

4.2%

of

med-

ical

school

faculty.4

Even

when

traditional

academic

productivity

metrics,

such

as

grants

and

publications,

are

adjusted

for,

studies

have

consistently

found

that

URM

faculty

are

less

likely

to

be

promoted.13'14

Further,

our

data

on

recruitment

programs

for

URM

students

suggests

that

most

medical

schools

employ

a

wide

variety

of

initiatives

to

encourage

applications

and

enrollment

by

URM

students.

However,

aside

from

summer

enrichment

programs

and

URM

student

recruiters,

schools

felt

that

most

other

programs

were

only

moderately

effective.

When

combined

with

the

data

on

barriers,

it

is

striking

that

recruitment

efforts

do

not

seem

to

directly

focus

on

the

barriers

identified

by

the

majority

of

schools:

faculty

diversity

and

the

strong

emphasis

that

schools

continue

to

place

on

MCAT

and

GPA

scores

as

admissions

criteria.

Lastly,

we

found

that

the

majority

of

medical

schools

tended

to

rate

themselves

highly

with

respect

to

their

performance

in

creating

a

diverse

student

body.

It

is

unclear

how

schools

evaluated

themselves,

as

we

found

only

weak

correlation

between

self-rated

success

scores

and

the

percentage

of

new

URM

stu-

dents.

As

most

schools

believe

they

are

doing

rather

well

at

URM

recruitment,

this

finding

suggests

that

many

schools,

on

their

own,

may

not

aggressively

pursue

the

additional

requisite

changes

needed

to

achieve

a

more

diverse

physician

workforce.

Limitations

to

our

study

include

the

low

response

rate

as

well

as

possible

discrepancies

between

the

med-

ical

schools'

views

on

URM

recruitment

and

those

of

other

groups,

such

as

students.

For

example,

while

stu-

dents

often

cite

lack

of

financial

resources

as

a

barrier

to

entering

and

succeeding

in

medical

school,'5"16

less

1230

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

UNDERREPRESENTED

MINORITY

RECRUITMENT

than

half

the

schools

in

this

study

felt

that

lack

of

finan-

cial

aid

or

parental

income

was

a

problem.

Our

nation

has

embarked

on

an

ambitious

agenda

of

eliminating

the

glaring

racial

and

ethnic

in-

equities

that

exist

in

our

healthcare

system.

Achiev-

ing

physician

workforce

diversity

will

be

an

impor-

tant

step

towards

achieving

this

goal,

and

our

study

shows

that

schools

are

investing

tremendous

efforts

into

minority

recruitment.

However,

our

study

also

suggests

that

current

initiatives

may

not

be

address-

ing

the

central

barriers

that

schools

themselves

iden-

tify-admissions

criteria

and

URM

presence

among

the

faculty.

Of

note,

these

are

institutional

barriers,

directly

amenable

to

intervention

by

the

schools

themselves.

Furthermore,

our

study

also

suggests

that

schools

may

have

difficulty

with

internal

evalu-

ation

of

their

recruitment

efforts,

perhaps

underscor-

ing

the

need

for

an

external

body

to

assist

with

the

development

of

diversity

goals

and

an

evaluation

of

their

performance.

Until

these

critical

issues

are

addressed,

we

fear

that

efforts

to

achieve

a

more

diverse

workforce

will

remain

at

an

impasse.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We

thank

Dr.

Nathan

Stinson

and

Jim

Simpson

of

the

OMH,

Mr.

Paul

Wright

of

AMSA,

Joan

Hedge-

cock

of

the

AMSA

Foundation,

Dr.

PJ

Maddox

and

Victoria

Doyon

of

George

Mason

University,

and

the

participants

on

the

AMSA

Diversity

Coalition

for

their

input

into

survey

development.

The

comments

in

this

manuscript

do

not

neces-

sarily

reflect

the

views

of

AMSA,

OMH,

NCMHD

nor

the

universities

or

hospitals

with

which

the

authors

are

affiliated.

REFERENCES

1.

Minority

students

in

medical

education:

facts

and

figures.

Washington,

DC:

Association

of

American

Medical

Colleges,

2002.

www.aamc.org/

publications/medicalschoolmatriculants.pdf.

2.

Overview

of

race

and

Hispanic

origin,

census

2000

brief.

Washington,

DC:

U.S.

Census

Bureau

Publication

#C2KBR/01-1;

2001.

Available

at

www.census.gov/prod/2001

pubs/c2kbrOl-1

.pdf.

3.

Missing

persons:

Minorities

in

the

Health

Professions.

Durham,

NC:

The

Sul-

livan

Commission

of

Diversity

in

the

Health

Workforce,

2004.

http://admis-

sions.duhs.duke.edu/sullivancommission/documents/Sullivan

Final-Report

_000.pdf.

4.

In

the

nation's

compelling

interest.

Ensuring

diversity

in

the

health

profes-

sions.

Washington,

DC:

National

Academy

of

Sciences

Press,

2004.

www.nap.edu/books/0309091

25X/html.

5.

McGaghie

W.

Perspective

on

medical

school

admission.

Acad

Med.

1990;65:136-139.

6.

Shea

S,

Fullilove

MT.

Entry

of

black

and

other

minority

students

into

U.S.

medical

schools.

Historical

perspective

and

recent

trends.

N

Engl

J

Med.

1985;313:932-940.

7.

Edwards

JC,

Elam

CL,

Wagoner

NE.

An

admission

model

for

medical

schools.

Acad

Med.

2001;76:1207-1212.

8.

Jones

BJ,

Borges

NJ.

The

contribution

of

noncognitive

characteristics

in

predicting

MCAT

scores.

Acad

Med.

2001;76:S52-S54.

9.

Albanese

MA,

Snow

MH,

Skochelak

SE,

et

al.

Assessing

personal

qualities

in

medical

school

admissions.

Acad

Med.

2003;78:313-321.

10.

Miller

HC.

Affirmative

Action

in

Medical

School

Admissions.

JAMA.

2003;289:3085-3086.

1

1.

Cregler

LL.

A

second

minority

mentorship

program.

Acad

Med.

1993;

68:148.

12.

Shields

PA.

A

survey

and

analysis

of

student

academic

support

pro-

grams

in

medical

schools,

focus:

underrepresented

minority

students.

J

NatI

Med

Assoc.

1994;86:373-377.

13.

Fang

D,

Moy

E,

Colburn

L,

et

al.

Racial

and

ethnic

disparities

in

faculty

promotion

in

academic

medicine.

JAMA.

2000;284:1085-1092.

14.

Palepu

A,

Carr

PL,

Friedman

RH,

et

al.

Minority

faculty

and

academic

rank

in

medicine.

JAMA.

1998;280:767-771.

15.

The

color

of

medicine:

strategies

for

increasing

diversity

in

the

U.S.

physi-

cian

workforce.

Boston:

Community

Catalyst,

2002.

www.community

cat.org/acrobat/The-Color_of_Medicine.pdf.

16.

Study

group

on

minority

medical

education.

Reston,

VA:

The

American

Medical

Student

Association,

1996.

www.amsa.org/pdf/study_meded.PDF.

A

We

Welcome

Your

Comments

The

Journal

of

the

National

Medical

Association

welcomes

your

Letters

to

the

Editor

about

articles

that

appear

in

the

JNMA

or

issues

relevant

to

minority

healthcare.

Address

correspondence

to

C

A

f

The

University

of

California,

Davis

School

of

Medicine

is

recruiting

for

faculty

members

at

the

Assistant/Associ-

ate/full

Professor

level

in

several

of

its

clinical

and

basic

science

departments.

These

include

positions

with

research,

teaching,

and/or

clinical

responsibilities

in

any

of

our

five

academic

series.

Specific

details

on

positions

including

required

educational

degrees,

experience,

and

responsibilities,

and

the

individual

to

contact

for

sub-

mission

of

an

application

can

be

found

at

the

following

website:

http://provost.ucdavis.edu/cfusion/emppost/

search.cfm

The

University

of

California,

Davis

is

an

affirmative

action/

equal

opportunity

employer

with

a

strong

commitment

to

achieving

diversity

in

its

faculty

and

staff.

OB/Gyn

Needed

in

San

Francisco

Bay

Area

O.AKCARE

A

BC/BE

OB/Gyn

is

needed

for

an

IMEDICAL

exciting

position

in

a

growing

GROUP

Maternal

Child

Health

department

at

a

County

Medical

Center

serv-

ing

diverse

populations.

The

OB/Gyn

will

be

required

to

perform

varied

services

in

Labor

&

Deliv-

ery,

Urgent

Care

and

clinics.

There

are

approxi-

mately

12

OB/Gyn

FTEs

serving

this

population.

We

offer

competitive

salaries

with

good

benefits.

Please

send

CV

to

Vishu

Lalchandani,

CAO,

Oak-

Care

Medical

Group,

Fax

(510)

437-9651

or

phone

(510)

437-4293

for

more

information.

JOURNAL

OF

THE

NATIONAL

MEDICAL

ASSOCIATION

VOL.

97,

NO.

9,

SEPTEMBER

2005

1231