White Paper:

How interest rate buy-downs can be used

to complement private capital financing

for energy efficiency projects

March 2023

Prepared by the California Alternative Energy and Advanced Transportation Financing Authority

Author: Kelly Delaney

Page 1 of 21

Executive summary

Energy efficiency retrofits are an important component of many utility, city, state and national goals to

facilitate the clean energy transition and mitigate the impacts of climate change. Energy usage is a

significant source of greenhouse gas emissions and has deep equity implications for low- and moderate-

income households, who often live in older, less efficient homes and face upfront cost barriers to

making efficiency retrofits or purchasing efficient appliances. Meeting these energy efficiency targets

will require the investment of billions of dollars, and financing will be a necessary source for some of

those costs. Public sector or utility collaboration with private capital financing can be a powerful tool to

help advance these goals while more efficiently leveraging public or ratepayer funds. Interest rate buy-

downs (IRBDs), in the form of a payment provided by financing program administrators directly to the

private capital provider to reduce the interest rate a customer pays for a financial product, are one of a

suite of tools programs can deploy to make financing offerings more attractive and increase uptake.

IRBDs can deliver various benefits, such as incentivizing certain project types (e.g., whole building

retrofits, or decarbonization/electrification projects), improving access for low- or moderate-income

borrower types, making projects more affordable for borrowers, and driving lender and contractor

participation in financing programs. Indeed, the financing programs that have obtained the highest

lending volume, such as the Tennessee Valley Authority or MassSaves HEAT in Massachusetts, have all

utilized IRBDs.

1

IRBDs do also generate challenges, as they can be complex to administer, and are

expensive.

Borrower uptake of financing is maximized when IRBDs are paired with other existing incentives, such as

rebates and/or credit enhancements, though they can also be effective when deployed independent of

other incentives. The most significant strength of buy-downs is their flexibility: IRBDs can be customized

by the amount of the buy-down, the loan term, the maximum and minimum project sizes, the types of

qualifying borrowers and project types, and more. Though they can be expensive, they can be applied in

a more targeted manner as or more easily than rebates. For example, if the goal is to improve low- or

moderate-income access to energy efficiency, a borrower’s financial status is automatically examined

(and thus easily identified for eligibility) as a part of the credit approval process but may not be

considered in typical rebate applications.

There are many variables to consider when setting up an IRBD, including available budget and the

capacity of lending partners. The relatively high costs of IRBDs may make them better suited for

targeted deployment if funding is limited, depending on available administrative capacity and program

goals. Otherwise, the establishment of a reliable, large, and long-term fund is necessary to encourage

ongoing lender and contractor participation. It is also very important, when targeting any financing

product at low- and moderate-income borrowers, that extra care is taken to ensure the borrowers can

afford to take on the new debt.

IRBDs can support California’s existing goals and targets to address the climate crisis and help spur much

needed momentum in energy efficiency retrofit financing. This tool can potentially generate significant

financial and energy savings for residents, as well as the number and scope of projects across the state.

With the state’s looming deadline of doubling energy efficiency savings and demand reductions in

electricity and natural gas end uses by January 1, 2030, any opportunity to increase momentum should

be considered.

1

https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/lbnl-1005754.pdf

Page 2 of 21

Introduction

This white paper provides an overview of key considerations for state and local policymakers, energy

efficiency program administrators, and program partners, such as financial institutions, on the use of

interest rate buy-downs (IRBDs) as a complement to private capital financing for clean energy building

upgrades and retrofits. While this paper will focus on California’s existing buildings, legislation, and

climate impact opportunity, many of the takeaways described here can be applied broadly to other

states.

Energy retrofits provide a significant opportunity to reduce energy use and greenhouse gas (GHG)

emissions in existing buildings, supporting the clean energy transition and mitigating the effects of

climate change. In California, existing homes and commercial spaces are responsible for approximately

35% of the state’s energy consumption and generate around 25 percent of its GHG emissions.

2

,

3

The

need for energy efficiency retrofitting and upgrading is noteworthy; more than 75 percent of California’s

estimated 13.7 million existing homes and 7.4 billion square feet of existing commercial space were built

before the state’s Building Energy Efficiency Standards were first developed in 1978.

4

,

5

There is also a growing push to decarbonize existing building stock by switching to electrical appliances

and equipment for cooking and heating. Electrifying residential buildings can potentially reduce GHG

emissions by 30-60 percent compared with mixed fuel homes, according to the California Air Resources

Board (CARB).

5

Switching to electric appliances in homes and businesses can also provide additional

health and safety benefits by eliminating the emission of indoor air pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide,

methane, and carbon monoxide typically produced by gas-burning appliances.

6

Clean energy financing helps advance energy efficiency goals

Meeting our energy efficiency targets will require the investment of billions of dollars, and financing will

be a necessary source for some of those costs. Financing can help customers achieve the types of energy

improvements they want without having to pay for everything up front or sacrificing the scope of

desired upgrades. Some borrowers may find additional value in financing because it allows them to

reserve cash for deployment in other ways.

Many utilities, green banks, and government agencies have long offered financing for energy efficiency

retrofits and upgrades in the building sector to help homeowners, renters and commercial customers

achieve energy savings. However, there are not enough tax and ratepayer funds to meet that financing

need.

7

Additional challenges stem from the organizational limitations of these public and utility

programs, which have little experience and/or capacity to aggressively scale financing programs.

To address this gap, some government and utility financing programs have opted to leverage private

capital to deliver energy efficiency financial products. However, private capital providers may be

hesitant to enter into the clean energy financing space, or may have more restrictive underwriting

requirements, due to concerns related to the risks and costs of lending for energy efficiency projects.

7,

8

Credit risk is of course a common concern: efficiency loans are typically unsecured as it can be difficult

for mainstream lenders to use efficiency as collateral. Many lenders are not accustomed to underwriting

2

https://www.energy.ca.gov/programs-and-topics/programs/energy-efficiency-existing-buildings

3

https://www.eia.gov/state/print.php?sid=CA

4

https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/reports/integrated-energy-policy-report/2021-integrated-energy-policy-report

5

https://ww2.arb.ca.gov/our-work/programs/building-decarbonization/existing-buildings

6

https://www.npr.org/2021/10/07/1015460605/gas-stove-emissions-climate-change-health-effects

7

https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/ee-financing-program-implementation-primer.pdf

8

https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u115.pdf

Page 3 of 21

to energy savings and it can be challenging to rely on contractor performance risk, and so most often

rely on standard measures of credit, which can be limiting on the residential side and especially complex

for commercial or multifamily properties. Transaction and administrative costs are also a concern;

lenders need high loan volumes and project sizes to feel comfortable entering a market.

9

It’s also

important that lenders be able to bundle energy efficiency loans and sell them on the secondary market,

in order to recapitalize their loan funds.

To encourage lender participation and expand borrower access to capital for energy upgrades, some

financing programs deploy credit enhancements to reduce lender or investor risk, such as loan loss

reserves, debt service reserve funds, and subordinated capital arrangements.

10

This allows the financing

programs to better leverage and extend the impact of their own funds.

IRBDs are another tool that programs can employ to support the growth of a clean energy financing

market and are very commonly utilized by large volume energy efficiency financing programs, such as

those in Michigan, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and New York.

Definition: Interest Rate Buy-down

A payment, provided by program administrators directly to the private capital provider, to reduce the

interest rate a customer pays for a financial product. The amount of the payment is typically the

present value of the difference between the “market” interest rate of the financial product over its

expected life and the reduced interest rate the customer will actually pay.

10

This white paper focuses on IRBDs deployed by utility or government programs to private capital

partners, but it’s important to note that they can be provided by a variety of actors in the energy

efficiency financing world. For example, residential home improvement contractors sometimes utilize

them as a marketing tool; while this approach is effective in that it is proven to help sell and close

projects, it is not clear how much the customer actually benefits, as contractors may then mark up other

prices, thereby eroding the customer’s savings.

The benefits and challenges of IRBDs

IRBDs offer a multitude of benefits, and challenges, across the stakeholder value chain. The depth of

these impacts depends on many factors, including organization capacity and program scope. Several

benefits are described below:

•

Reduced loan costs for the borrowers. A reduced monthly payment, using the example of a

term loan serviced monthly, saves money for the borrower and may better align the cost of

energy efficiency improvements with their energy savings.

10

This in turn may help drive

customer adoption of financing for energy efficiency improvements, or support the decision to

invest in deeper, more comprehensive (and thus, expensive) improvements. Indeed, by reducing

the overall cost of financing, IRBDs may be able to improve the cost-effectiveness of these types

of investments, which in some cases (e.g., given the higher cost of electricity compared to gas)

may initially increase costs for borrowers. Loan affordability is especially meaningful from a

commercial financing perspective, as businesses tend to prioritize revenue generation over

savings.

9

https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/see_action_loan_performance_full_study_final.pdf

10

https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2014/06/f16/credit_enhancement_guide.pdf

Page 4 of 21

•

Increased loan/project volume and value: IRBDs can also support the growth of the energy

efficiency financing market or program by increasing the attractiveness of available financing

products. Even as energy financing programs are becoming more common, research indicates

that many are not yet fully penetrating the market of potential customers.

11

It is widely

accepted that merely having the option of competitive financing, even credit-enhanced

financing with below-market terms and rates, will not by itself motivate customers to initiate a

project. However, once the decision to pursue energy efficiency has been made, affordable

financing can enable projects to move forward to completion. Program administrators have also

observed that marketing makes a “significant positive difference in the number of applications

received.”

11

The prevalence of low or no-cost financing in the personal vehicle financing sector,

for example, demonstrates its power as a marketing tool. During times of economic uncertainty

and rising interest rates, as in the current environment, this message may be even more

attractive.

•

Incentive for contractors and lenders to participate in the financing program: because IRBDs

can increase project volume, they can be an appealing recruitment method to attract new

lenders and contractors to the financing program.

12

This feature may make IRBD marketing

promotions particularly useful for low-volume or younger programs seeking to gain traction.

•

Improved loan performance: As a further boon to lenders, lower interest rates may also

support loan portfolio performance. In 2022 the State and Local Energy Efficiency Action

Network reviewed the financial performance of four large and long-running residential energy

efficiency financing programs across the United States. They found that, for all programs

combined, the chance of loan charge-off increased by 2.29 percentage points for every a 1-

percentage point increase in interest rate.

13

•

Streamlined loan processing and project timelines: Lenders also report that a significant benefit

of IRBDs is the momentum they generate. Once internal processes are set up, less time is spent

negotiating rates with the borrower, and there are “fewer touches” needed between both

parties. For territories where utilities run On-Bill Financing (OBF) programs, which typically also

offer 0% rates but can take months to qualify for and utilize, the relative speed of private

finance companies (who can approve customers for financing in a matter of hours) can be a

competitive differentiating factor for both the lender and the borrower, especially in an

emergency equipment replacement situation. OBF programs also often face budget challenges;

supporting private capital financing market share growth with IRBDs can in fact allow utilities to

target limited OBF resources towards complicated projects that are less easily served by the

private market.

Deploying IRBDs does comes with challenges and limitations.

•

High, non-revolving costs: Residential financing programs in Vermont, Connecticut and New

York have also found that while very attractive to residents, buying interest rates down can be

expensive.

14

,

15

Like rebates, IRBD funds have one-time use and do not “revolve” in the same way

that some credit enhancement tools like loan loss reserves can, and thus the long-term impact

of such capital is limited.

15

Some research suggests, though, that the costs of IRBDs can be

11

https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u115.pdf

12

https://publicservice.vermont.gov/sites/dps/files/documents/Renewable_Energy/CEDF/Reports/2020CleanEnergyFinanceRpt_CEDF.pdf

13

https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/see_action_loan_performance_full_study_final.pdf

14

https://publicservice.vermont.gov/sites/dps/files/documents/Renewable_Energy/CEDF/Reports/2020CleanEnergyFinanceRpt_CEDF.pdf

15

https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u115.pdf

Page 5 of 21

minimized up to 20% by being efficient with the buy-down amount (e.g. not buying the loan all

the way down to 0%) and offering short loan terms.

16

Of note is that no IRBD program reviewed

for this paper includes a function to “reclaim” buy-down funds if a borrower defaults or pays off

the loan early.

•

Flexibility facilitates better targeting but can be difficult to manage: Some programs deploy

different buy-down rates for different types of projects or borrowers. While this can be very

effective, complexity is difficult to communicate succinctly in marketing and sales efforts, which

can affect uptake.

Additionally, if the source of the IRBD funds is external to the deployer of the funds (for

example, a statewide financing program receiving funds from multiple local utilities),

complications may arise based on each entity’s organizational limitations, requirements, and

mission.

17

Each contributor may have its unique requirements regarding, for example, project

type eligibility, pre-approvals, and post-project inspections. This increases administrative

complexity and costs for the deploying program and can result in payment delays for

contractors, undermining contractor participation.

IRBDs may be especially useful for low- and moderate-income borrowers

It is worth drawing special attention to the benefits that IRBDs may generate for low- and moderate-

income (LMI) borrowers in the residential sector. Improving LMI access to energy efficiency is a policy

priority for many government and utility programs. Low-income individuals are more likely to live in less

efficient, older housing that is expensive to heat, cool, or light and may also need expensive structural

work before efficiency improvements can be made. Plug loads from appliances and other consumer

electronics also tend to be higher in low-income households; research indicates that access to energy

efficient appliances, such as washers and dryers, dishwashers, and water heaters, becomes more

prevalent with the increase of household income for both homeowners and renters.

18

According to the

California 2021 Low-income Potential and Goals Study, 57% of the electric savings potential for low

income households by 2030 is associated with appliances and other plug loads

19

. The California Public

Utilities Commission (CPUC) also found that 13.3 percent of California’s lower-income households spend

more than 15 percent of their income on electricity service, and more than 6 percent of these

households spend more than 10 percent of their income on gas service.

20

The CPUC’s 2020 Annual

Affordability Report notes that essential electricity service is projected to become less affordable for

vulnerable Californians, and hotter regions in California will continue to face greater burdens in

affording essential utility services.

21

16

https://www.njcleanenergy.com/files/file/public_comments/Summary%20of%20Proposed%20Changes%205-14-15.pdf

17

https://www.energytrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SELP_Final_Report10.pdf

18

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421519300205

19

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/new-best-practices-are-unlocking-demand-side-management-value-in-utility-on/621163/

20

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/news-and-updates/all-news/cpuc-issues-affordability-report-highlighting-trends-in-affordability

21

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/divisions/energy-division/documents/affordability-proceeding/2020/2020-annual-

affordability-report.pdf

Page 6 of 21

How financing can best serve LMI borrowers — or whether it should — is a topic of much debate. A fair

argument can be made that financing is not the best tool for LMI households, which may struggle to

meet basic needs or lack financial reserves. The specter of unfair or fraudulent lending practices, and the

possibility of saddling borrowers with debt they cannot repay, deepens skepticism about the

appropriateness of financing for this socioeconomic group. Financing programs must always take care to

educate private lending partners to be aware of this, and lenders themselves must carefully consider

loan affordability when underwriting a loan for LMI borrowers. State-administered or pseudo-public

green banks must also ensure sufficient consumer protections when determining borrower eligibility

rules.

However, some households, such as those that

would be considered moderate-income, often

do not qualify for grant and other assistance

programs that target low- and very low-

income customers; at the same time, they do

not have sufficient income or savings to afford

the upfront costs of energy saving

improvements on their own, even after

rebates (which are rarely directly accessible at

retail points of sale). This is particularly

prevalent when it comes to purchasing

appliances or new equipment, due to the

upfront cost barrier.

22

Indeed, a recent study found that about 12% of

Michigan households fell into a coverage gap of eligibility for energy efficiency loans due to moderate

income; they were unlikely to be approved for a loan but also did not qualify for direct-install or other

low-income incentive programs.

23

This is sometimes referred to as the energy efficiency “donut hole”

(Figure 1).

24

A reduced monthly payment facilitated via an IRBD could help make a financed energy

efficiency project possible, or even help the borrower invest in a more efficient product or deeper

retrofit.

25

Likewise, it could make an energy efficient choice feasible in the event of emergency

replacement of an appliance or a heating or cooling unit, which are the majority of most equipment

upgrade projects.

26

Financing for subsidized or naturally occurring affordable housing (NOAH) multifamily properties can

also be difficult to facilitate since, like LMI households, these properties may not much have flexibility

with existing cashflow to make large monthly payments, and they may be restricted from raising rental

prices to cover the debt repayment.

25

In both cases, IRBDs may help bring down repayment costs to

make energy efficiency projects more palatable.

22

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421519300205

23

https://justurbanenergy.files.wordpress.com/2020/01/1-s2.0-s0306261919319944-main.pdf

24

https://urbanenergyjusticelab.com/2020/02/27/study-finds-an-energy-efficiency-funding-coverage-gap-exists-in-michigan/

25

https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/ee-financing-lmi.pdf

26

https://www.aceee.org/files/proceedings/2000/data/papers/SS00_Panel6_Paper21.pdf

Government

sponsored low-

income household

weatherization

Traditional

financing options

for higher-income,

credit worthy

households

Energy Efficiency

Donut Hole

(Coverage gap for

moderate income

households)

Figure 1 The Energy Efficiency "Donut Hole” explaining the coverage

gap in financing accessibility.

Page 7 of 21

The positive impacts of IRBDs

Across the U.S., a variety of energy efficiency financing programs have reported noteworthy positive

impacts from offering IRBDs.

Connecticut:

During a 7-month long promotional campaign for a 0.99% loan, the Connecticut Green Bank saw loan

volume increase “6x”, a 22 percent increase in new contractor enrollment, and a 20 percent increase in

the number of contractors selling financing. Loan volume continued to increase after the promotion

ended and contractors began offering their own IRBDs, indicating that the IRBD helped contractors

improve their comfort with selling financing to customers.

27

Massachusetts:

In a survey of ~950 borrowers who utilized the state’s 0% interest rate residential HEAT loan program,

85 percent of customers reported that the loan allowed them to make improvements that they

otherwise would have passed over.

28

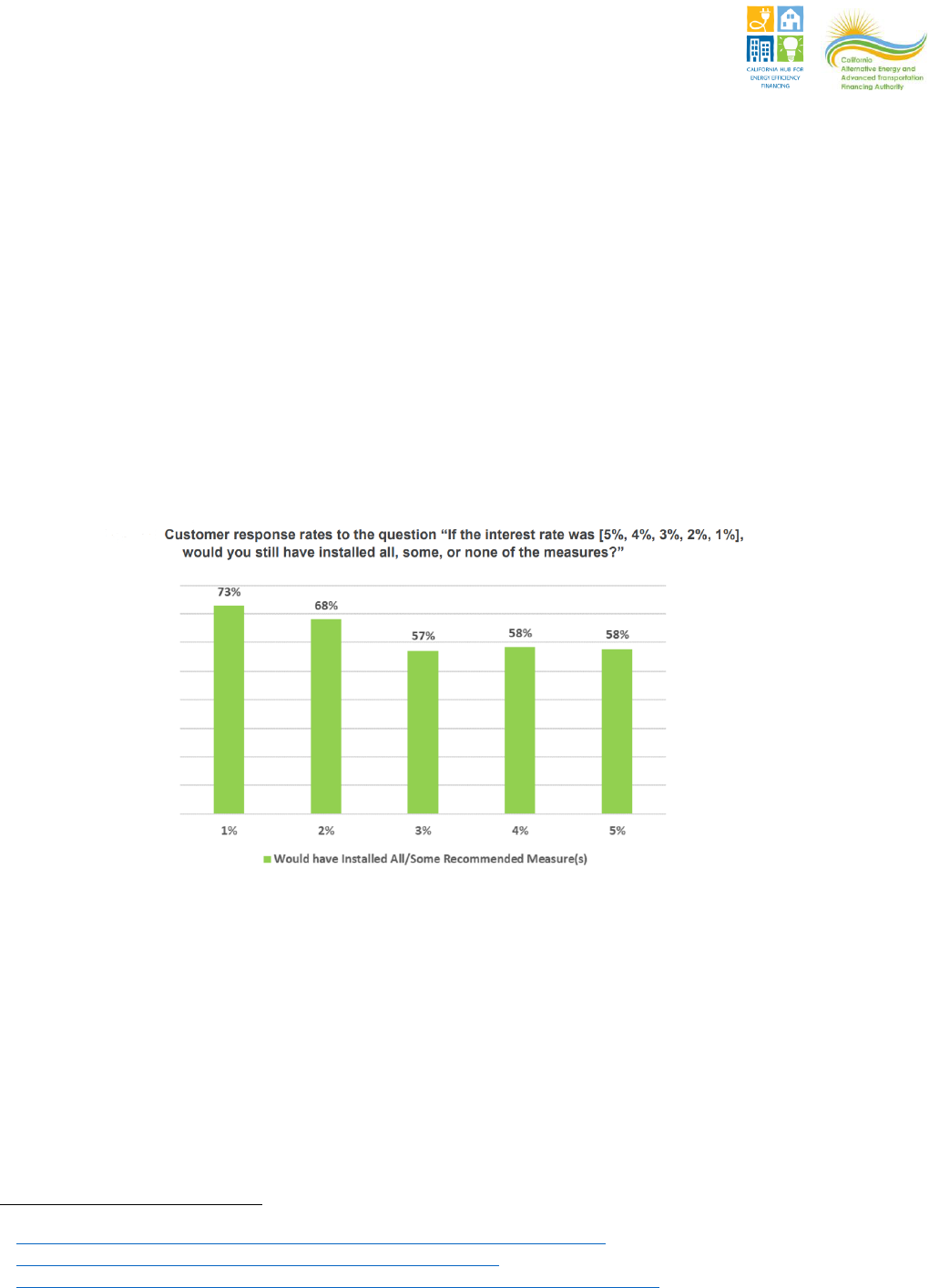

90% indicated that the 0% interest rate was central to their

decision to take out the loan, with (hypothetical) participation declining as interest rates rose (Figure

2).

29

Figure 2 Survey responses indicating effect of interest rate on project scope for the Massachusetts loan program.

27

https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdf/conferences/eeff/2018/3A-Elliott-Hill-O%27Neill.pdf

28

https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-07/making-it-count-final-v2.pdf

29

https://ma-eeac.org/wp-content/uploads/MA-RES-37-HEAT-Loan-Evaluation-Report_FINAL_01AUG2018.pdf

Page 8 of 21

Rhode Island

A HEAT loan is also available in Rhode Island, where borrowers, contractors and lenders report that

buying the interest rate down to 0% is an important component of their participation. 51% of loan

recipients reported that they wouldn’t have used the loan without the 0% interest (Figure 3).

30

Figure 3 Maximum interest rate at which respondents in Rhode Island who partook in the HEAT loan program would have

considered a HEAT Loan

Michigan:

The Michigan Saves residential financing program found after a series of experiments that the offered

interest rate was a significant predictor of initial participation in the financing program. Upgrade rates

were also higher when the interest rate offered was lower, and the most successful interest rate was 0%

for a 10-year loan term, with 48 percent of participants opting to upgrade. Higher interest rate offers

resulted in decreased participation (Figure 4).

31

Figure 4 Percentage of borrower uptake based on offered interest rate in Michigan loan program.

30

http://rieermc.ri.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/heat-loan-assessment-final-report_111918.pdf

31

https://michigansaves.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/BetterBuildings-for-Michigan-Final-Report.pdf

Page 9 of 21

Michigan’s multifamily program also noted a utility-funded IRBD (to 0%) was “critical to increasing

participation in the program and continues to drive participation.

32

Likewise, the Michigan Saves commercial financing program found that buying down interest rates to

0% was key to doubling loan volume in one year, especially for small businesses; contractors also cited

low interest rates as a key part of their sales pitch. Michigan Saves has continued to utilize IRBDs for

commercial projects for nearly a decade now, in various configurations.

Pennsylvania:

The Keystone HELP loan program offered a tiered financing product, with lower interest rates of 3.875%

for larger products feature comprehensive upgrades, and 6.99% for smaller projects. According to the

President of AFC First Financial, this tiered approach has not only influenced market demand, but also

encouraged contractors to embrace whole home performance.

33

32

https://www.seealliance.org/wp-content/uploads/REEO_MF_Report.pdf

33

https://eta-publications.lbl.gov/sites/default/files/report-low-res-bnl-3960e.pdf

Page 10 of 21

IRBD configurations

When considering how to design and deploy IRBDs, a variety of variables will affect scope, impacts, and

costs. Each must be considered carefully by the implementing program within the context of funding

availability, goals and targets, and other relevant regulatory factors. The more complex the eligibility

and verification requirements are, the higher the administrative costs and the greater likelihood that

borrowers or contractors may be turned off by the (perceived or real) transactional “friction” of

participating in the program.

The buy-down amount

While the personal vehicle financing market has conditioned consumers to respond to 0% financing

opportunities, buy-downs do not always have to cover the entire cost of capital. One national energy

efficiency financing provider interviewed for this paper noted that IRBDs do not need to be 0% to be

effective; in fact, they are quite effective at moving the market when they are competitively below

market rate, such as below 3.99%, though this “frame” can shift depending on the current economic

climate and cost of capital. An assessment of financing programs across the country commissioned by

California’s joint utilities also indicates that while 0% helps with uptake, it is not necessary for success.

34

A 2018 survey of 910 Vermont residents asking what interest rate they considered to be “affordable”

appears to support the interviewee’s suggestion: two thirds of respondents deemed interest rates 4% or

lower as affordable, while only 3% of respondents thought that interest rates at 5-6% were affordable.

35

Examples from Michigan, Rhode Island, and Massachusetts above also indicate that openness to

financing drops off between 3% and 5%.

Several programs base their buy-down amount on project scope or other factors. For example, in

Connecticut, Eversource Energy buys interest rates down for commercial customers to 1.99% for

projects with multiple energy saving measures, while single measure projects are only eligible for 2.99%.

In New York, the utility National Grid offers different rates based on different term lengths (0% for 24- or

36-month terms, or 1.99% for 48- and 60-month terms). As mentioned above, a program in

Pennsylvania offers loan interest rates for whole home projects and has seen contractors lean towards

deeper retrofits in order to capture the lower rate.

Maximum and minimum project sizes

Project size limitations may be necessary to protect IRBD funds. For example, large commercial projects

can cost hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars. Without a project size “cap,” IRBD budgets

could be at risk of being too quickly and disproportionately spent.

When setting project size maximums, some programs adjust the caps to accommodate the nature of the

project, such as average costs for different types of common upgrades, or even to incentivize certain

types of upgrades. For example, Jersey Central Power & Light’s (JCP&L) Commercial and Industrial

Financing Program, offering 0% financing for up to five years, sets a limit of $75,000 for direct install

projects, $150,000 for “Prescriptive” upgrade projects, and $250,000 for customers participating in

JCP&L’s Energy Management program. It is important the cap be appropriate to the potential or average

project size; one small business IRBD promotion started with project maximums of $25,000 and a 36-

month term, and while contractors were interested in leveraging the promotion, they struggled to fit

projects into the narrow scope needed for qualification. Participating lenders and contractors later

indicated that the term and price restriction were not flexible enough to meet the market’s needs.

36

34

https://www.calmac.org/publications/Existing_Programs_Review_FINAL.pdf

35

https://publicservice.vermont.gov/sites/dps/files/documents/Renewable_Energy/CEDF/Reports/2020CleanEnergyFinanceRpt_CEDF.pdf

36

Interview with Jonathan Verhoef, Program Specialist for the GoGreen Business Financing program in California.

Page 11 of 21

Some programs also set caps based on the cost of each financeable measure, or estimated or deemed

KW savings, in order to dissuade contractors from marking up project costs to take advantage of “free”

buy-down dollars. For example, the program might limit financing and buy-downs for residential heat

pump water heaters to $4,000 maximum; a project could go over that amount, but the calculated buy-

down amount wouldn’t consider the excess costs.

Other incentives and regulatory requirements

Many financing programs, especially utility-run programs, allow, encourage, or even require the use of

rebates for projects receiving buy-downs. Many programs unsurprisingly report the most uptake when

both rebates and 0% or low-cost financing are available. For very large commercial and industrial

projects, additional incentives to bring down the total project cost may be key to achieving positive or at

least neutral cashflow, since buy-downs can’t decrease monthly payments beyond the 0%.

Of note is that some programs are considering replacing rebates entirely with IRBD programs, describing

the decision as more equitable since the amount of the buy-down can be targeted by borrower need. In

this way, IRBDs may be a more cost-effective use of funds over the long run, as some rebate amounts

can be quite substantial. Interestingly, some IRBD recipients have reported that the buy-downs are

preferable to rebates.

37

Borrowers are not always aware of all available incentive options, or may find

the process of researching, analyzing, and applying for separate rebates, and then waiting for the funds

to be delivered, to be too complicated or time-consuming to pursue. IRBDs are a simple way to utilize

incentive dollars because they fit seamlessly into an existing loan program and often don’t require the

borrower to make a separate application or deal with an additional funding source.

For some programs, however, replacing rebates with IRBDs is not possible as state or other regulations

only allow the program to claim deemed savings based on dollars spent from rebate budget pools.

Project scope and type

As described above, some programs offer a buy-down in specific cases. A more targeted deployment of

a buy-down, such as by project or borrower type, can support or amplify certain program goals.

One example of a project type that could be specifically incentivized by an IRBD is a comprehensive

“whole home” energy retrofit. Comprehensive retrofits can greatly enhance energy savings and GHG

reductions since more than 65 percent of building emissions result primarily from space and water

heating in existing buildings.

38

Focusing on building envelopes and high-performance windows reduces

energy costs regardless of fuel type by effectively creating additional thermal storage and reducing

heating and cooling costs while improving overall comfort for residents.

39

Decarbonization projects, such

as switching from a gas water heater to an electric heat pump water heater, are another target.

It is with expensive, more complex projects like these that the appeal and impact of low or 0% interest

financing can be maximized. Whole home projects can be very expensive, ranging from $25,000 to

$100,000. Decarbonization measures like heat pumps, and their installation costs, are typically more

expensive than their gas counterparts. Decarbonization measures also often require expensive electrical

infrastructure upgrades to handle the increased electrical loads. One CPUC study showed that at least 65

percent of existing buildings would need some type of infrastructure upgrade (wiring, plumbing or

electrical panel upgrades) to install a heat pump water heater; these upgrades can cost over $2,000.

40

37

https://www.energytrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SELP_Final_Report10.pdf

38

https://www.buildingdecarb.org/uploads/3/0/7/3/30734489/bdc_roadmap_2_12_19.pdf

39

https://www.energy.ca.gov/data-reports/reports/integrated-energy-policy-report/2021-integrated-energy-policy-report

40

https://efiling.energy.ca.gov/GetDocument.aspx?tn=241599

Page 12 of 21

Some programs have attempted to achieve additional energy savings by requiring that measures be

complementary in this way, although as noted previously, this approach requires additional

administrative capacity for compliance and enforcement. The Maryland Home Energy Loan Program

(MHELP) initially required duct sealing and insulation if a new furnace was purchased as part of the

program, but this approach was abandoned after program administrators perceived that it was reducing

borrower participation. The MHELP program, and Pennsylvania’s HELP program, instead later opted for

a tiered interest rate system, with lower rates when complementary measures are bundled.

41

Maximum and minimum loan terms

Programs may also wish to set limits on the length of payback periods for loans utilizing IRBDs. Buy-

downs do not always need to cover a loan’s entire term (See the next section, “Borrower Type,” for an

example of this principle in action). Shorter loan periods can also reduce the total cost of the IRBD for

the program.

42

This approach may be prudent if program funds are limited. However, setting loan term

limits can also limit overall efficiency results, as borrowers and lenders may have to adjust the size and

scope of the project to meet the borrower’s budgetary or energy saving requirements.

Borrower type

IRBDs can also be targeted towards particular borrower types. Unlike with most rebates, borrowers’

financial situations are considered during the financing process, making it easier to identify borrowers

who may have lower income or otherwise be in need of additional financial assistance. Low- and

moderate-income households often struggle with higher energy costs due to occupying less efficient

homes and appliances, and being renters. These households tend to also have lower participation rates

in energy efficiency programs, especially those requiring higher upfront investment (such as rebates).

43

One utility interviewed for this paper was at the time considering buy-downs based on borrower need.

Thanks to a credit enhancement offered by the utility for its private capital financing partner, every

borrower is already able to access a 10-year HVAC loan at 4.99%. Under the additional proposed IRBD

program, borrowers who are considered “high need” would receive a 0% buy-down for the entire 10-

year loan term, while “medium need” borrowers’ interest rates would be bought down to 0% for the

first five years and “low need” borrowers’ rates would be bought down for the first year only.

Borrower need does not have to be limited to financial need, either. Tools like the CalEnviroScreen Tool

can be used to identify residents in disadvantaged communities on the basis of pollution burden,

population characteristics and socioeconomic factors. According to the 2022 Draft Integrated Energy

Policy Report issued by the California Energy Commission (CEC), people of color make up 90% of the

population of the top 10% most polluted neighborhoods in California.

44

People in these communities can

be more vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as periods of extreme heat in which air

conditioning may be weak.

45

In fact, many census tracts identified as disadvantaged by CalEnviroScreen

are in the same geographic regions where the CPUC reports high affordability issues.

46

On the commercial side, IRBDs can also help drive demand for small business financing, which is a

difficult market to serve as the investments don’t always pay for themselves and spare cash for monthly

41

https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/publications/researchreports/u115.pdf

42

https://www.njcleanenergy.com/files/file/public_comments/Summary%20of%20Proposed%20Changes%205-14-15.pdf

43

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0301421519300205

44

https://efiling.energy.ca.gov/GetDocument.aspx?tn=247338

45

https://efiling.energy.ca.gov/GetDocument.aspx?tn=247337

46

https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/-/media/cpuc-website/divisions/energy-division/documents/affordability-proceeding/2020/2020-annual-

affordability-report.pdf

Page 13 of 21

payments can be hard to find. Similar to targeting LMI borrowers, financing programs can also target

specific types of commercial customers, such as places of worship or nonprofits.

Timing

The amount of time that an IRBD program is available is important, especially if the goal is to incentivize

the development of new projects or when serving larger commercial or public entities. Larger and/or

more bureaucratic institutions often need several months or even years to develop and analyze a

project plan, gain the appropriate approvals, and obtain funding. If the timeframe is too short, there is a

risk that only projects that were already conceived and farther along in planning or development stages

may be able to take advantage of it, in which case the IRBD’s influence on the stimulation of projects is

less likely and more difficult to measure.

47

Lenders and contractors may also be dissuaded from

participating in the financing program if IRBD funding runs out too quickly; as investing in marketing

efforts often relies on long term incentive availability. However, deadlines can be useful tools for

generating demand, and even small or short-term buy-down promotions can be usefully deployed,

especially to help spark demand for financing programs struggling to gain traction.

Buy-down deployment cadence and infrastructure; lender capacity

In the early stages of developing an IRBD, financing programs should communicate early and often with

participating lenders to understand what experience and concerns they may have. Some smaller lenders

may not have the organizational or technological capacity to take on IRBDs, especially more complex

configurations that, for example, limit the buy-down to a portion of the loan or loan term.

Financing programs also should consider how buy-down funds will be transmitted to lender partners.

Some programs put aside the funds in a separate account to which a lender has access; on a periodic

basis (e.g., monthly or even on a project-by-project basis) the lender reports on loan originations using

IRBDs and pulls down the necessary buy-down amount from the shared account. This method is

reported as preferable by many lenders interviewed for this white paper, as it allows them to transact

with clear visibility into the amount of available buy-down funds. One less common approach is for the

financing program to provide the buy-down funds directly to the contractor, as a “final payment”

representing an amount the lender typically holds back from the contractor until the project is

complete. This method would only work for projects that include pre-funding for contractors, meaning

that the contractor is partially paid for their work by the customer’s lender before installation is

complete.

Another method is for buy-down funds to be transmitted to the lender in alignment with each

customer’s monthly remittance. This method can protect limited cash reserves by spreading out the

costs of each IRBD over time, allowing more buy-downs to be deployed simultaneously. It should be

noted, however, that this method is not common or popular amongst private capital providers

interviewed for this paper. One interviewee acknowledged that this could be done, but that it is not

preferred and would be administratively burdensome to reconcile each payment and corresponding

buy-down portion every month. Another lender concluded it would not be possible for them to

participate in a program taking this approach, as they need the entire buy-down amount attached to the

loan in order to sell the loan on the secondary market shortly after origination.

47

https://www.energytrust.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/SELP_Final_Report10.pdf

Page 14 of 21

Example loans utilizing IRBDs

Project type: residential “whole home” decarbonization (credit enhancement + IRBD)

In this scenario, the homeowner is doing a relatively significant upgrade with HVAC and building

envelope measures. The financing program already offers participating lenders a credit enhancement in

the form of a loan loss reserve, which incentivizes the lender to offer lower interest rates and longer

payback periods. Even with the credit enhancement, the borrower enjoys additional benefits with the

IRBD, saving more than $3,000 in interest.

Project

Heat pump water heater (55 gallon)

Gas to electric, includes relocation to garage

$4,000

Unitary heat pump (18 SEER)

$10,000

Attic insulation

$2,000

Air and duct sealing

$1,500

Electrical panel upgrade

$2,000

Rebates (based on TECH Clean California 2022 incentive amounts)

-$4,100

TOTAL

$15,400

Financing Options

Private consumer

loan

Private capital + energy

efficiency financing program

+ credit enhancement

Private capital + energy

efficiency financing program +

credit enhancement + IRBD

Interest rate

10.7%

4.4%

(interest rates reduced due to credit

enhancement provided by program

partner)

0%

*bought down from 4.4% (interest

rates reduced due to credit

enhancement provided by program

partner)

Payback period

60 months

120 months

*extended payback period due to

credit enhancement provided by

program partner

120 months

*extended payback period due to credit

enhancement provided by program

partner

Up front cost

$0

$0

$0

Monthly payment

$332/mo

$158/mo

$128/mo

Borrower’s total

payment

$19,952

$4,552 total interest

paid

$19,063

$3,663 total interest paid

$15,400

$0 in total interest paid

$3,663 total interest saved w IRBD

Program’s IRBD Cost

NA

NA

$2,959

Page 15 of 21

Project type: residential heat pump upgrade (different buy-down amounts based on

project and borrower types)

Two homeowners are each switching to an electric heat pump. One homeowner is considered high-need

due to income. In this scenario, the financing program buys interest rates down to 2.99% for single

measure loans, and 0% for high-need borrowers. There is no credit enhancement offered by this

program. No private consumer loan is offered as an example because the provided base interest-rate

scenario (pre-IRBD) represents the same effect.

Even though the monthly payment difference is negligible between the single-measure borrower and

the high-need borrower, the high-need borrower finds additional benefits by saving just over $3,000 in

interest payments over the life of the loan. Though the financing program must bear the higher interest

payment cost, they still see savings in not having to pay the full $9,000 for directly installing the heat

pump.

Project

Unitary heat pump (18 SEER)

$10,000

Rebates (based on TECH Clean California 2022 incentive amounts)

-$1,000

TOTAL

$9,000

Financing Options

Energy efficiency financing program +

private capital + “single-measure” IRBD

Energy efficiency financing program +

private capital + “high-need borrower”

IRBD

Interest rate

2.99%

*bought down from 7.99%

0%

*bought down from 12.99%

Payback period

60 months

60 months

Up front cost

$0

$0

Monthly payment

$162/mo

*would be $182/mo without IRBD

$150/mo

*would be $204/mo without IRBD

Borrower’s total

payment

$9,701

$701 total interest paid

$1,246 total interest saved w IRBD

$9,000

$0 total interest paid

$3,284 total interest saved w IRBD

Program’s IRBD Cost

$1,024

$2,406

Page 16 of 21

Project type: low-income residential borrower purchasing energy efficient appliance

In this example, a "high need” renter is purchasing an efficient heat pump dryer appliance. While the

monthly payment cost savings are negligible between the bought-down loan’s interest rate and the

original private loan, the borrower may be more likely to purchase the efficient product due to the low

or $0 upfront cost that financing provides, which rebates cannot on their own. Over $300 in interest

savings can also be impactful for this borrower.

Project

Heat pump dryer

$1,249

TOTAL

$1,249

Financing Options

Private consumer loan

Energy efficiency financing program +

private capital + “high-need borrower”

IRBD

Interest rate

9.99%

0%

Payback period

60 months

60 months

Up front cost

$0

$0

Monthly payment

$27/mo

$21/mo

Borrower’s total

payment

$1,591

$342 total interest paid

$1,249

$0 total interest paid

Program’s IRBD Cost

NA

$269

Page 17 of 21

Project type: small business HVAC and lighting upgrade

In this scenario, a small business owner is updating existing HVAC and lighting systems with more

efficient versions. There is no credit enhancement offered by the financing program in this scenario;

only the IRBD.

In this case, even a 2% buy-down is enough to bring the monthly payment down, and most importantly

provide significant savings in overall interest paid.

Project

3 rooftop unit/packaged HVAC systems

$26,350

LED lighting fixtures

$8,980

Rebate (based on PG&E 2022 incentive amounts)

-$1,350

TOTAL

$33,980

Financing Options

Private commercial loan

Energy efficiency financing program +

private capital + IRBD

Interest rate

8.50%

5.05%

*after buy-down from 8.50%

Payback period

84 months

84 months

Up front cost

$0

$0

Monthly payment

$538/mo

$481/mo

Borrower’s total

payment

$45,202

$11,222 total interest paid

$40,410

$6,430 total interest paid

$4,793 total interest saved w IRBD

Program’s IRBD Cost

NA

$3,603

Page 18 of 21

Project type: affordable multifamily property “whole building” decarbonization

In this scenario, a master-metered affordable multifamily property is decarbonizing. The 0% interest rate

reduces the monthly loan amount and saves the property $14,000 in interest. As affordable multifamily

properties typically operate within very limited margins and debt structures, significant savings can

mean the difference between being able to move forward with a project or not.

The cost of the buy-down, at nearly $11,000, is significant.

Project

Central heat pump water heater

$37,000

Electrical panel upgrade

$6,000

20 unitary wall/ceiling heat pumps

$21,000

20 Electric stoves

$20,000

Rebates (based on TECH Clean California 2022 incentive amounts)

-$34,000

TOTAL

$50,000

Financing Options

Private commercial loan

Energy efficiency financing program +

private capital + IRBD

Interest rate

8.50%

0%

*after buy-down

Payback period

72 months

72 months

Up front cost

$0

$0

Monthly payment

$888/mo

$694/mo

Borrower’s total

payment

$64,002

$14,002 total interest paid

$50,000

$0 total interest paid

$14,002 total interest saved w IRBD

Program’s IRBD Cost

NA

$10,939

Page 19 of 21

Appendix

Examples: National Landscape

Below are examples of how other energy efficiency financing programs are utilizing IRBDs for energy

efficiency or other energy upgrade-related projects.

Implementing

organization(s)

National Energy Improvement Fund & Atlantic City Electric

Website

Financing offer with IRBD

Residential

Minimum loan $2,500, maximum loan $15,000. Improvements

must qualify for rebates.

Only eligible for qualifying energy efficiency measures.

0% for 3, 5 or 7 years.

Geographic area served

Borrower must be an Atlantic City Electric utility account holder.

Implementing

organization(s)

National Energy Improvement Fund & First Energy Jersey

Central Power & Light

Website

Financing offer with IRBD

Residential: HVAC and Water Heating Equipment

Minimum loan $2,500, maximum loan $15,000.

0% for up to 5 years and up to 7 years for low to moderate income

customers.

Rebate eligible.

Multifamily: Engineered Solutions

Minimum loan $2,500, maximum loan $2,000/unit, up to $250,000

per project with 40 units or less.

0% for up to 5 years and up to 10 years for low to moderate

income customers/buildings.

Rebate eligible.

Commercial: Prescriptive and Custom – Equipment and/or

Building Improvements

Minimum loan $2,500, maximum loan $150,000 for Prescriptive

and $250,000 for Custom projects.

0% for up to 5 years.

Rebate eligible.

Geographic area served

Borrower(s) must be the First Energy Jersey Central Power & Light

utility account holder.

Page 20 of 21

Implementing

organization(s)

National Energy Improvement Fund & Eversource Energy

Website

Financing offer with IRBD

Small business and Municipal

0% for projects up to $100,000; below-market rate for projects

above $100,000.

12 to 48 months.

Rebate eligible.

Commercial and Industrial

1.99% for comprehensive/multi-measure projects or 2.99% for

single measure projects up to $100,000; below-market rate for

projects above $100,000.

Up to 60 months.

Rebate eligible.

Geographic area served

Customers in Connecticut receiving an Eversource or AVANGRID

rebate through Energive CT Energy Efficiency Programs.

Implementing

organization(s)

Efficiency Vermont (an energy efficiency utility) - Home

Energy Loan

Website

Financing offer with IRBD

Residential

Varying interest rates available for borrowers based on household

income and the loan term:

Income

< 5 years

5 – 10 years

10 – 15 years

<$60,000

0%

1.99%

2.99%

$60,000 -

$90,000

0%

2.99%

3.99%

>$90,000

4.99%

5.99%

6.99%

Maximum 15 years.

Geographic area served

Vermont residents (Vermont Gas customers only eligible for

electric appliances and heat pump heating and cooling systems).